Ei, foetus, baby

Trudy Dehue

Atlas contact, 2023

De dragers

Daan Borrel

De Bezige Bij, 2024

Bedenktijd

Meredith Greer

De Bezige Bij, 2023

Oersoep

Bregje Hofstede

Das Mag, 2023

On pregnancy’s bloody histories & its visceral fictions

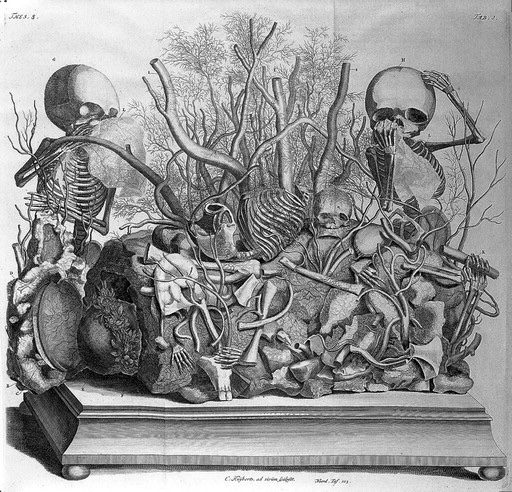

As a botanist, anatomist and the chief obstetrician to Amsterdam’s poor in the 1670’s, Frederik Ruysch taught the city’s midwives, delivered babies, and examined miscarried fetuses. He didn’t just examine them; he liked to tinker with them too. He brought many fetal bodies home with him to the Bloemgracht number 15, where he prepared and embalmed them. With some, he got especially creative. As Trudy Dehue writes in her brilliant history of pregnancy research, Ei, foetus, baby (2023), Ruysch conserved one such fetus in a bottle « resting on a pillow of placenta », while giving another « a little collar and a little hat, along with a bed of blood vessel », while a third was placed in the opened jaw of an equally dead snake. Ruysch grew very skilled at deconstructing the little bodies, and reconstructing them in a new, cutesy pose. Like an early modern Anne Geddes, he would rest the bodies on a bed of gall, kidney or bladder stones, for example, or « he gave them objects to hold, like a translucent little handkerchief made of very thin, veined human membrane, that one such tiny skeleton would mournfully hold up to its hollow little eye sockets. »1

Female reproductive health has long been the business of men. In Ei, foetus, baby (Egg, Fetus, Baby), Trudy Dehue examines the lengths to which these men have gone to answer the question of what happens during conception, in a pregnant belly and during labor. Dehue is a professor emeritus of History and Theory of Science at the University of Groningen; the book charts five centuries of Western academic knowledge about pregnancy: its methods, its assumptions, its effects. It is a richly layered history covering roughly five centuries of research, mostly focused on the Netherlands but often widening its scope to the rest of the Western world, and broadly leading up to our current moment: from the first creative imaginations of what a sperm and egg looked like and how they relate to each other, via the horrifying testimonials of seventeenth-century surgeons who proudly butchered their patients,2 to X-rays, ultrasound technology and mobile fetal monitoring systems strapped on pregnant bellies.

The ever-clearer image of the fetus that emerged made the lives of pregnant women better and safer, but has at the same time played into the hands of anti-women’s rights movements. Progress isn’t always progress. As she writes, « People who can get pregnant have, with great pain and at the risk of death, sustained the human race — and not exclusively at their own instigation. » With an astonishing number of sources, Dehue tracks the pain and risk of death that pregnant women3 have faced specifically to advance the scientific knowledge around pregnancy. Many of their names are lost to history, unlike those of the men doing the (often, frankly, unhinged) experiments set up to advance that knowledge.

The book is bursting with appalling facts and findings, tragic, infuriating, extremely funny — I constantly found myself re-telling what I learned from this book in appropriate and less appropriate social situations. Like the fact that at-home pregnancy tests have only been available to women since the 1970s; in, say, the fifty years before that, pregnancy could be demonstrated by injecting a mouse or a frog with a woman’s urine.4 Until that time, you weren’t strictly speaking pregnant until you started feeling a tickling sensation in your belly, after around four months. Or the fact that pretty soon after the invention of X-ray technology there were signs that radiation without proper protection could cause serious bodily harm and genetic damage to the fetus, but that testimonials about it were blithely dismissed as « superstition ». Or that one of the first movements to urge caution with X-ray technology was German National Socialism, because it was « concerned about the loss of quality of the Aryan race. » Or that the introduction of ultrasound technology in pregnancy care came about after one doctor visited a friend’s shipyard, where it was used to check welding seams in ships. Shipyard workers were playing around with the equipment, using it on their limbs — and that’s what gave the doctor the idea. The book is a wonderful record of the fact that furthering knowledge is not a clean straight line of lofty advancement toward the now, but a random and bloody mess.

The book stays with me when reading fiction. Around the time of the release of Ei, foetus, baby, three Dutch novels were published, all by young female writers, all well-received, all touching on pregnancy — not on the science surrounding pregnancy (traditionally the domain of men), but on the pure, personally felt experience of it (traditionally not the domain of men, although some men will gladly explain it to you anyway). One is about abortion, one about the period of carrying a child, and one about the lyrical savagery of childbirth and the postpartum period. I often find it fairly insufferable to read personal stories about pregnancy or birth — though no doubt I’ve missed a lot of wonderful work.5 The writing about pregnancy and early motherhood that I’ve come across in my reading life so far is often either fluffy, or it’s mostly about the horror of being taken over physically and mentally by a parasite that doesn’t even allow you a glass of chardonnay. These three books don’t go down that road. Although very different in form and tone, they share an understanding that pregnancy and childbirth come with the inevitability of becoming completely identified with, and taken over by, your physicality.

Bedenktijd (Consideration period6), by the writer and editor Meredith Greer, is not so much a novel as it a collection of essays and autobiographical writings about the lonely time in her life when she underwent an abortion in the midst of the corona pandemic. She experiences the procedure in double isolation — without a partner (the other party responsible for the pregnancy doesn’t want anything to do with it) and in a world-wide lockdown. The forced distance she feels from others mirrors the distance she feels from her changing body. The narrative sections about that time are alternated with essays on, for example, the inadequacy of language, the lack of rituals to do with losing a fetus, liminality and grief. The book’s internal design is pretty playful: dotted throughout are shorter excerpts — poetry, an adaptation of a psalm, or people’s hateful opinions about women and abortion printed in shades of gray. Those opinions start in the margins but gradually dwarf the main text on the page.

« Abortion is a sledgehammer of a word, » Greer writes in the book’s first essay. It flattens. Every abortion takes place in a different context, in different circumstances, with different emotions or motivations — but the term reduces it to « the essence of a physical cessation. A breaking off. » And then, of course, the language used around abortion « becomes a weapon in a political battlefield », with no room for nuance. « When one camp gains ground, » as Greer writes, « it is automatically at the expense of the other side. If it’s a clump of cells, it’s just a medical procedure. If it’s budding life, it’s infanticide. The words are binding and definitive; they vie for an absolute truth. » For many people, having an abortion doesn’t feel like just any other medical procedure. But by acknowledging that instead of using clinically-distant vocabularies (Embryo. Fetus. Cells.) when discussing the experience, you might risk saying something that could be interpreted as a passionate argument for limiting women’s physical autonomy. Something that was formerly living is now dead, something that is dead could have been brutally murdered. By choosing your words, you choose your consequences.

Dehue’s Ei, foetus, baby traces the twisted history of the word « abortion », and of its weaponization. Before the nineteenth century, ending an unwanted pregnancy was known in Dutch as « het opwekken van de maandstonden » or « het doen misvallen », which would translate, respectively, to something like « inducing the monthly flow » and « to misfall » — surprisingly cosy terms, that imply some agency on a woman’s part. They revolve around her and her cycle, not around terminating whatever it is that has sprouted inside her. You’d be less likely to be sent to jail for « inducing the monthly flow » than for « killing unborn life ».

The term « abortus » appeared first in Dutch sources in the first half of the nineteenth century, in the context of the premature, unintentional expulsion of animal and human fetuses. In other words: a miscarriage — a term that has been around for much longer.

The sudden application of Latin terms should set off alarm bells, Dehue warns, because weighty Latin terms indicate that religious or medical authorities have gotten involved. « Abortus » first entered the scene at a time when it was fashionable in medical circles to try to prevent miscarriages. Women who’d maybe had a few miscarriages and were thus considered to have a « dispositio abortiva » were subjected to the most colorful treatments to try to preserve their pregnancies. An 1843 obstetric encyclopedia that Dehue quotes characterizes women with this particular disposition as typically « full-blooded, irritable, highly sensitive, nervous, hysterical, lymphatic, blond, weak » and « very fat », with sex drives that were either abnormally high or abnormally low. Dehue lists idiotic treatments she saw described in medical sources of the time — all conjured up by a procession of men heartily congratulating one another on their brilliant inventions. Some highlights: to prevent miscarriage, a woman had to maintain a « horizontal position for months », avoid any form of « fright, wrath and unexpected joy », not ride or drive on bad roads, not take any naps or foot baths. Such were the don’ts. The do’s included bloodletting, mercury treatments, cold-water enemas and the application of ointments with caustic substances. The cervix should be rubbed with belladonna or borax with saffron, or dotted with leeches. The sores that could develop after very painful leech bites could then be treated with a burning ointment. All this presumes miscarriage as a disease or failure, but just for the record: today it’s been established that ten to fifteen percent of pregnancies end in miscarriage. There’s nothing to be done about that — in the 1980s we learned that miscarriage is usually a healthy response of the body to faults in fetal development. Something that, according to Dehue, a nineteenth-century physician from Utrecht had already found after years of examining miscarriages. When presenting his findings at a conference in 1849, he was apparently widely mocked by colleagues.

A new term emerged on the scene around 1900: « abortus provocatus », coined by the Dutch obstetrician and gynecologist Hector Treub, referred to a miscarriage induced deliberately by a doctor to save a woman’s life. This was an outlawed procedure at the time, which of course resulted in many unnecessary deaths. Treub lobbied for the law to change and for abortion to be allowed in cases when a woman’s life was in danger. Treub’s opposition had mainly to do with the law’s Catholic premise: it was illegal to remove a fetus that had been alive, given that this procedure then took away its chance of being baptized. Catholic values didn’t belong in Dutch law, Treub argued, and the illegal act should be the harming of the woman, not the removal of the fetus.

Because of this ban, most women of the time were forced to use home remedies or visit an unqualified « ladies’ expert » to get rid of an early unwanted pregnancy — which, if those attempts went wrong (pierced uterine walls, chemical substances left in the womb, sepsis), led to them ending up in hospital wards with Treub and his fellow gynecologists.

Treub showed himself to be less of a champion of women’s rights by introducing a second term to distinguish what unqualified ladies’ experts did from what proper gynecologists did. The lesson he took away from his daily practice was that only doctors should be allowed to make the moral and medical decision to terminate a pregnancy. His camp wanted to fight both against religious interference in his field, as well as against the idea that a woman could decide for herself if she should be pregnant or not, and could hire someone (uncredentialed, but sometimes perfectly capable) to help her. To make the difference clear, he and his supporters added another word to the political battlefield of his time: « abortus provocatus criminalis ». The criminalis part meaning: the pregnancy was unwanted, its end instigated by the woman.

In another time and place, that word might have been a powerful weapon. But in his, it didn’t matter much: in 1911, the Christian government in the Netherlands introduced the Zedelijkheidswet, a deeply intrusive law which, among many other things, outlawed helping a woman induce a miscarriage. Anyone doing so — qualified or unqualified — would risk imprisonment for up to three years. Since anything to do with the procedure was from then on criminalis, the term could just be reduced to « abortus »7 — full circle. Abortion, a sledgehammer of a word. Especially considering that today, it excludes its former meaning of « miscarriage » and has been so flattened to come to mean only an obligatory, legal and moral truth. Just termination. No absolution. No relief.

What does a fetus look like, at different stages of it being carried to full term? We didn’t always know, but today we hardly have the option of not knowing. How do we see it, and how has the fetus been observed over the years? In Daan Borrel’s De dragers (The carriers) three women of different generations become mothers — one in 1996, one in 2023 and one in 2035. With each chapter of the novel, the perspective changes. The women have very different experiences during and after their pregnancy, but all run into similar questions of care, solidarity, motherhood, their changing relationship to their bodies and their changing roles in society. Borrel describes the mother in 1996 and the one in 2023 primarily in their postpartum period, but the woman in 2035 — a very observant baker and « intimacy activist » named Vita — is followed during her pregnancy.

Vita is a surrogate for a gay couple — but more out of conviction than out of the goodness of her heart. She is a member of the organization Wombs For All — « as a collective, we put our wombs to work for a more intimate world, we split the act of carrying from motherhood because we don’t believe in motherhood in the service of the heteronormative family, when the world is freed from the nuclear family, only then true family will emerge. »8 Even in 2035, this is a controversial idea. Later she calls carrying a child only for yourself « smallminded ». On the three separate days that we read her perspective, she goes to an ultrasound appointment with expectant fathers Miko and Lucas, visits Miko’s mother Marion, and on the last day she goes into labor — surrounded by Lucas, Miko and Marion.

Vita enjoys carrying new life inside her but considers the process with great matter-of-factness and distance. She observes her surroundings and Lucas, Miko, and Marion keenly from her own little island, with seemingly very few observations about what she carries within her. There is some intimacy to be found in the fact that Vita addresses the growing bub in her belly directly. As Vita’s first chapter opens: « someone has thrown eggs against my front door, and because of that it suddenly feels like I have to explain myself to you, or at least talk to you, let you hear from me, I mean, we practically live under the same roof. » Sometimes she notes how special it is to feel life stirring inside of her, but those times can be counted on one hand. For example, when she hears heart activity during her first visit to an obstetrician with Miko and Lucas: « from the device emerges a rhythmic beat, with my eyes closed the four of us swim like whales deep in the ocean, it’s fucking amazing. » Later, during her first meeting with Marion, who has a cat on her lap: « she tickles the slender animal in her neck and I feel how you turn languidly, not just your movement but life itself feels slow in those moments. » On the day she goes into labor, she wakes up with an orgasm (« no mount everest, rather a speed bump, it seems to have turned into a routine since I carry you »), and the image of the swimming whale returns. As she notes how much peace and comfort there is between Lucas and his mother-in-law Marion:

perhaps marion raised miko in a particular way because he would choose lucas, does the future shape us in the same way as the past and present? in my belly you glide slowly like a whale just below the surface to the right, I put my hand on the spot where the movement is, yes I think so too I reply out loud

Although she doesn’t seem to be looking for it directly, Vita does eventually find deep connection and intimacy in the process of carrying for others, and in observing those others. When she’s about to go into labor, she has a conversation with Miko during a walk, in which he advises her to reconnect with her own mother.

I look at his sweet sweet face and understand how his face sits in my belly, his body in my body, that for a moment he was so close, then my cervix seems to clench around something and let go again

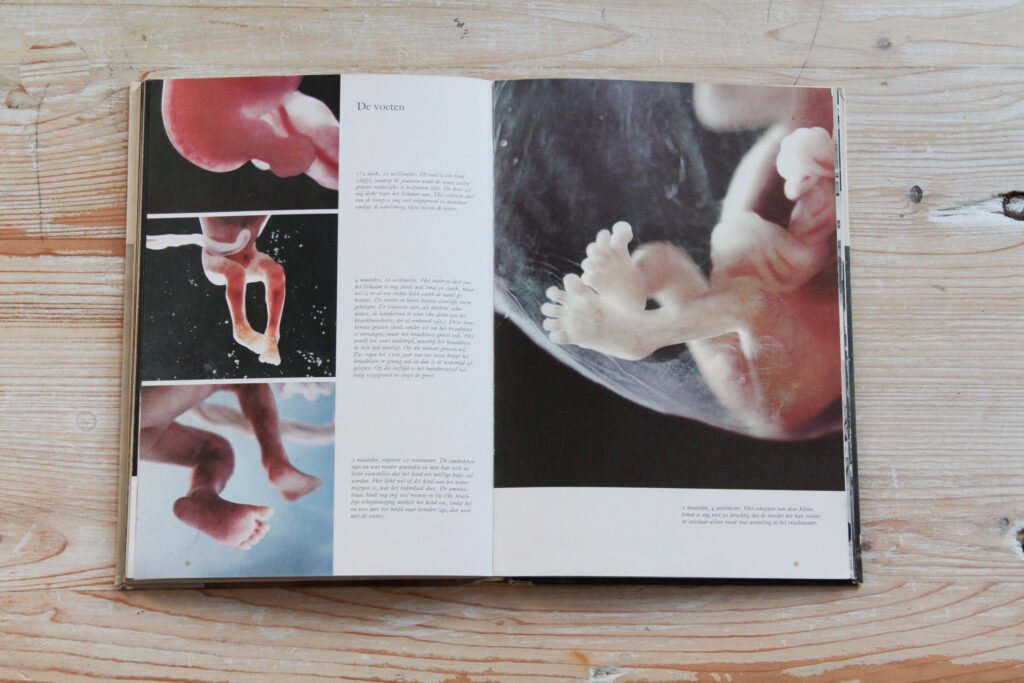

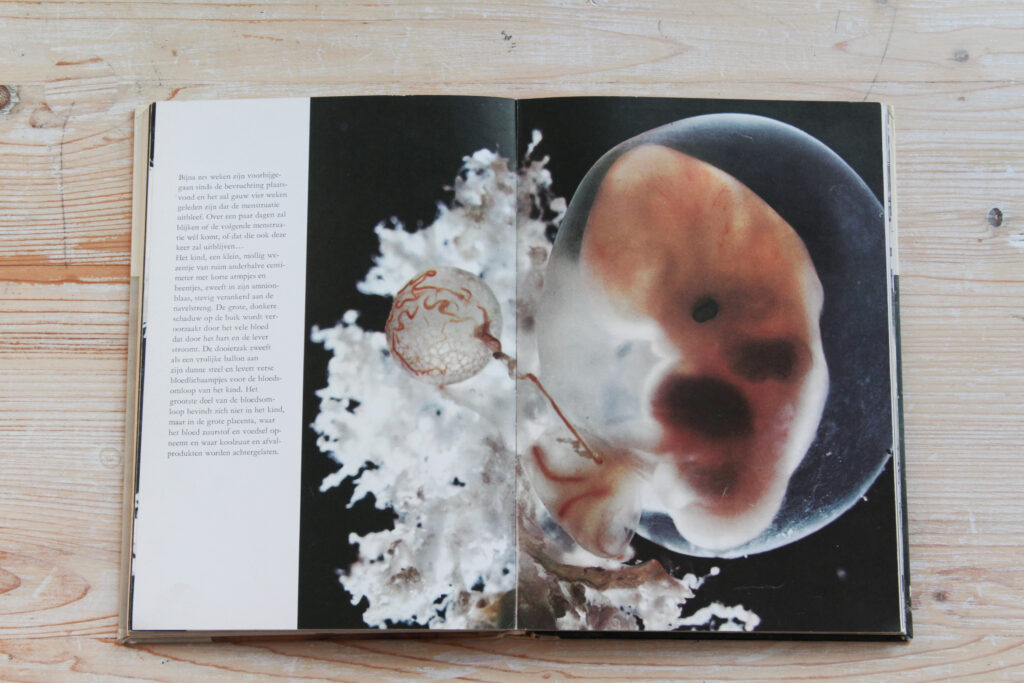

His sweet sweet face. The image of a fetus while being carried to term: there’s something wonderful and deeply intimate about it. We’ve seen it, in the warm puddle of the womb, quietly growing from a clump of cells to a complete looking but semi-transparent human of only a few centimeters head to toe — to the pudgy baby crammed inside its mother’s uterine walls, waiting to be born. The three generations of new mothers in De dragers are all pregnant in a time of ultrasound technology being routine during pregnancy check-ups (there seems to be no fancy new gadget for this in 2035, I’m sad to report). But before ultrasound, images of the development from embryo to full-grown fetus became widely known through best-selling colorful photo books like The First Nine Months of Life (1962) by Geraldine Lux Flanagan and A Child is Born (1965) by photographer Lennart Nilsson. Photographs of translucent micro-babies in amniotic fluid are awe-inspiring, almost mystical. In some of Nilsson’s photographs, the fetuses seem to float through the universe. The photographs come to us as if they were taken, somehow, in the womb, though that would be utterly impossible. The reality of how those pictures came to be is fairly dark: most of them are not of children about to be born, but of aborted fetuses.

Dehue’s history of fetus portraiture starts much earlier. In 1865, the Swiss embryologist Wilhelm His, a pioneer in his field, invented the « microtome », a device that sliced research objects into wafer-thin pieces, which proved very handy for embryos from two to about eight weeks.9 The specimens that were donated to him he cleaned, prepared and sliced, after which he could view the membranes under a microscope. From 1880 onwards, His published a series of books about the subject, and drew a first « calendar » of embryonic development seen week-by-week. Dehue observes that studies by His and the embryologists who followed him almost never mention the women who produced the embryos. For example, in his series of illustrated books, the German anatomist Franz Keibel (who had worked with His) warmly and appreciatively name-checks the doctors who donated this or that specimen, but mentions the woman from whom it came only when indicating that her cause of death left its condition pristine: « the embryo of table 23 was taken from the uterus of a murder victim » it’s noted in one of Keibel’s books from 1908, for example, or « the woman from whom the egg originated committed suicide by swallowing kali causticum. » Dehue found these micro-obituaries by searching the 350 pages of this book for the word « Frau », which she encountered five times.

Between 1930 and the mid-50s, the American neurologist Davenport Hooker of the University of Pittsburg filmed his experiments with live embryos and fetuses. The footage shows how still-living embryos outside the womb respond to certain stimuli — being lightly touched with a horsehair or tiny glass rod, stroked or gently pinched. According to Dehue, Hooker obtained some 140 human embryos and fetuses through gynecologists, « after a spontaneous or surgical abortion because a woman’s pregnancy was considered a ‘contra-indication’, for example, in the case of tuberculosis, high blood pressure, syphilis, epilepsy, intellectual disability and nymphomania. » The specimens were taken out of the woman through an abdominal incision and were placed in a bath of salt water. Hooker and his team could then film and experiment for a maximum of twenty minutes, because that’s as long as a fetus without oxygen supply could survive. « It’s all appallingly harsh, » are the words Dehue uses for it.

One of Davenport Hooker’s collaborators was the biologist Geraldine Lux Flanagan, who understood the value such footage could have outside of the scientific world. The First Nine Months of Life (1962), in fact, is richly illustrated with stills from Hooker’s work. It’s an educational book, the preface of which marvels about the fact that « We are the first generation to be able to have a clear picture of the course of our development from a single cell to an individual, active and responsive in most of the nine months before birth. » Lux Flanagan goes on to call these pre-birth individuals « babies », and the book — indeed the title alone — conjures the expectation that the images in it are of unborn children with a whole life ahead of them, still nestled warmly in their mother’s wombs. But in reality, creating these images involved, as Dehue writes « opened-up women, and surgically aborted embryos and fetuses deprived of oxygen, who were in a tub of water rather than a womb. »

Lennart Nilsson’s A Child is Born (1965), a wildly successful and colorful photobook, likewise suggested that these were all pictures of living beings that were, Dehue quotes the book, « preparing for life on earth ». But Nilsson mostly used deceased embryos and fetuses from a clinic. He himself put them in poses (having one serenely suck its thumb, for instance), and presented on an embellished background. He edited their skin color (blue became pink) and removed blood stains and other unattractive blemishes.

The autofictional Oersoep (Primordial soup) by the writer Bregje Hofstede opens with the birth of the narrator’s daughter, in a house in the French countryside. It’s a bestial, transcendental, trippy and primal experience, occupying an unstable shadowland of physicality, bodily fluids and pain — excruciating pain. It’s the kind of experience, Hofstede writes, that makes her lose herself, that allows her to reach through the « protective layer » around her life, where she can probe what world lies beyond « the membrane of what is fit to be seen ». The book becomes a search for a gritty corporeal spirituality, an experience she has begun to crave.

There is not much point in recounting these opening passages, because it boils down to: she gives birth. The magic is in the language, with which Hofstede drags a reader into this shadowland; it’s an almost physical experience for the reader, too. I suspect the transcendental state she describes will be recognizable to anyone who has been in a situation where the mind has fully surrendered to the suffering body — I recognized it from giving birth to my own daughter three years ago, and from bouts of delirious fever. Hofstede writes that she has used the word « pain » for other ailments, but that in this case « the only thing to come somewhat close is that broad heavy damp rot with which the blood announces itself, that feeling around your waist on your flanks and on your back to disintegrate and break off from your own stalks like a fruit turned to dark jelly. » And less poetically but still very appropriately: « how else can something so small hurt so much, unleash such power, this cuckoo chick pushing me out of my own nest. »

On the waves of pain, she gets into something I’ll call a transcendental rapture:

I feel it with my back. It’s as if the finest threads run from there, gossamer swarming swaying sprigs that float around, swirling through the air and straight through all things, so light and agile that they reach through atomic nooks and crannies, flutteringly bending along vibrating with the vibration of a magnetic or electric field (…), threads that like the strands of the finest algae float along an incomprehensible current

When she closes her eyes, she loses her sense of being in a living room surrounded by granite walls: « absolutely oceanic or actually cosmically big this room, with my eyes closed I don’t even feel the walls anymore. » She writes of having fallen backwards through her back, falling into a « wall-less space outside of the space », a « place without time that pushed the living room away ». That living room, containing her partner and the midwife, has been reduced to a:

little husk very far away, there at the farthest edge,

all the way there, all the way on the exterior I hear him talk

So rarefied the world has become

The film of the balloon

The skin of the fruit

that shiny,

that shrill shell of sound

She returns to the midwife, who points out to her that her daughter is announcing herself. « She guides my hand between my legs and something’s there that has my warmth and is made of my body but which my touch does not bring back to me. »

Once the child is born, she misses that endless, limitless place she was transported to during her labor. She wants to go back, « not to the indescribable pain of that night but to the immersion in a life that’s overflowing its banks. » She yearns to experience again « how the life that flows through me from time to time expands until it’s almost unbearably greater than I am. »

I wonder if Hofstede grew up Catholic, because her description of childbirth, her submission to the pain and the subsequent transcendental experience, turn into something, for lack of a better word, sacramental. A flagellation needed to reach beyond herself. Trudy Dehue did grow up in Catholic circles, and one of the more pointed throughlines in Ei, foetus, baby is the active role of the Catholic Church in abortions through the ages. The term Dehue suggests for this interference is the « abortus provocatus religiosus ». Although detailed nowhere in the Bible, the idea that a fetus in the womb already possesses a soul arose early in Christianity — a soul that, as was established in the third century, is charged with original sin, for which it can only find reprieve through baptism. Augustine would argue in the fifth century that unbaptized and unborn souls ended up in the « eternal flames »; Dehue also quotes the twelfth-century bishop Fulgentius, according to whom small children who died in « the womb of the mother » without being baptized « will be punished by the eternal torture of unquenchable fire. »

For centuries, Catholic pastors have sacrificed pregnant women in mortal danger so as to « save » the fetus’s soul. Most Church elders agreed that in the case of an impending miscarriage or a seriously ill pregnant woman, it was necessary to cut open the mother and have the fetus baptized by a priest in the seconds or minutes that it would still be alive. The soul of the mother, having been baptized at birth herself, was safe, so she could be ignored in the process. Few church authorities, it would seem, had enough faith in their Almighty God to trust that He could maybe find a solution for his unborn flock Himself. Dehue cites only Thomas Aquinas, who in his Summa Theologiae (1265) argued that a baptism marks the beginning of a person’s independent existence, and thus there was no point baptizing a fetus. He needn’t have bothered: in 1615 it was enshrined by Pope Paul V in the priestly manual Rituale Romanum as a papal decree: « si mater pregnant mortuarium fuerit, foetus quamprimum cautè extrahatur, ac si virus fuerit baptizetur », or, « if the pregnant mother dies, the fetus should be extracted as quickly and carefully as possible, and if still alive, baptized. » Consequently, it became a sin not to baptize an unborn fetus doomed to die, and the woman — whose life could potentially have been saved — would now also die in the procedure.10

Several of Dehue’s chapters detail the consequences of this papal decree in the centuries since, and those details are at once horrific — half-witted village clergymen having to decide whether a pregnant woman was in mortal distress or not — and horrifically inventive — for instance sprinkling a fetus with baptismal water in the womb, with syringes forced vaginally into an already severely tormented woman. Dehue spins from her sources a dark thread that runs from the third century to our time. These practices were still prescribed in some form in Catholic handbooks well into the 1950s.

Pulling that thread, one cannot help but see the term « mother died in childbirth » in a new, grim light. Only in 2007 did the Vatican’s International Theological Commission decide that, as Dehue puts it, « God may have somehow laid out a path to heaven for unbaptized children after all. »

Even when she moves on to other topics, the 1615 papal decree often lingers somewhere in the background. Around 1900, the aforementioned Hector Treub was lobbying against the practice of pastors cutting a fetus from a sick woman’s womb to baptize it: that practise was legal, but it was illegal for Treub and his medical colleagues to safely remove a fetus to save the mother. The notion of anti-abortionists today that an embryo is a form of unborn life that needs to be protected no matter the cost, can be traced back to the idea that it’s a creature with a soul.

I read Oersoep earlier this year, while in the process of trying to get pregnant with a second child. I read Bedenktijd and De dragers over the summer, in the weeks after a first ultrasound scan, during which the sonographer called the seven-week-old little bag of throbbing blubber on the screen « a very beautiful baby » with a « strong heartbeat ». I read most of Ei, Foetus, Baby in the days after the ten-week sonogram had shown no more sign of life.

At first, I thought it would be difficult to keep going in Dehue’s book while miscarrying. But I quickly realized that reading about the various horrors inflicted on pregnant women over the centuries was a cathartic way to handle my own potent mix of disappointment, sadness and rage. At the very least, it made me thankful that this terrible but very common thing had happened here and now, instead of in, say, the eighteenth century, when I’d have been at the mercy of some toothless, grimy, most likely drunk butcher. But it wasn’t just that. Reading Dehue’s history made me realize that while the care and medication I received was very modern, my experience in itself isn’t modern at all — it exists, in its way, outside of time. I could isolate the tune of my own pregnancy and miscarriage in the immense chorus of experiences that women have been having in a thousand variations, since the invention of the uterus.

The embryo a few millimeters long was called a « very beautiful baby » by our technician — at a time in my pregnancy when, had I lived a century earlier, I couldn’t even have been sure I was pregnant. It sounds cute to call a tiny blob a « baby », to listen to « the heart » at such an early stage, but it is not completely innocent. Ultrasound technology gives us a fetus in full view for nine months, ready for its close-up. Dehue’s final chapters consider the implications of that constant visibility. New technology can discover all sorts of developmental issues in an early stage (progress!), but at the same time it installs a persistent image of a fetus as an independent, individual being — as the baby it may become. At seven weeks there’s no such thing as a heart, and an embryo and fetus are not yet a baby. What’s recorded are signals from a « heart-tube-in-progress », which is a great sign of fetal health, but calling it a « heartbeat » is romantic nonsense: an insidious cuteness, widely weaponized by anti-abortionists. Not only by lobby groups guilt-tripping women who seek abortions, but also by policy makers seeking to outlaw abortion from the moment there’s a « heartbeat ».

Thanks to centuries of medical research and progress, pregnancy and childbirth have become immeasurably safer for women and babies. But in some areas, very little changes. With the visualization of the fetus, Dehue writes, « the age-old soul has merely been made material ». What used to be a fetus with a soul that had to be saved, has now become a visible baby-in-waiting that has to be protected at all costs. The sin of not saving the fetus’ soul (at the expense of the mother) has become the sin of murdering a baby. Surprise! In both the old and the new scenario, women lose.

What can novels do? Maybe it’s simple to say it, but they can capture human experience like no scientific approach ever could. These novels find words for something that cannot be measured in any systematic way, but that can completely reprogram a person to her deepest fibers. In the context of abortion, pregnancy, labor, women’s reproductive rights, words can be used as political weapons, sure, but they can also be used to build a truthful entrance into this shared experience. Giving birth, of course, is an experience that wildly differs from person to person, except in the fact that it was, to say the least, a Big Day for all of us. For myself, a novel like Hofstede’s had the gift of safely bringing me back to the mind-boggling distress and bewilderment I felt that morning and afternoon three years ago (my daughter was polite enough to enter this world within business hours), to revisit and understand that state of being in a way I’ve never been able to in conversations with friends, in reading an article about it or by scrolling through some pregnancy influencer’s account.

Ei, foetus, baby does something entirely different, of course, although I admit no other chunky history of science has ever moved me like this one did. Like a crystal-clear sonogram, it lays bare in stunning detail how our current understanding of pregnancy and birth came about — complete with all its blemishes, bad cells and developmental defects.

- None of the discussed works have been translated into English yet, so all translations are mine. ↩︎

- Dehue singles out one who seems relatively compassionate, namely Paul Portal, the obstetrician of the Parisian hospital Hôtel Dieu, who wrote in his handbook that an afterbirth that’s stuck in the womb should be taken out of a woman as carefully « as if one were ‘picking the flesh out of a tangerine’ ») ↩︎

- Dehue is aware of the limitations of the term « women ». In this book, she still most often prefers it over « pregnant people » because she feels it would be anachronistic to do otherwise in discussing most of this history. I follow her line in this piece — I do think that having an English translation for the gender-unspecific Dutch noun « zwangere » would be helpful (« a pregnant »?). ↩︎

- In the mouse, a positive result could be read from a change in its ovaries. The frog would change color. ↩︎

- I’m very open to suggestions! ↩︎

- The title of the book refers to five-day waiting period women in the Netherlands legally had to undergo after indicating to a doctor that they wanted an abortion. This compulsory period was lifted in 2023, the year the book came out. ↩︎

- It wasn’t until 1984 that a law was passed in the Netherlands defining situations in which an abortion could legally be performed. ↩︎

- In the chapters written from Vita’s perspective, there is virtually no punctuation, only short sentences without capital letters, centered on the page. This, apparently, is how people in 2035 will write! For the readability of this piece and to facilitate the layout of this magazine, I let the sentences run in full and added commas. ↩︎

- Today, we’ve made the distinction that an embryo becomes a fetus by the ninth week of the pregnancy. ↩︎

- Historically, a caesarean section would usually kill a woman. Only since the second half of the twentieth century, it’s become likely for women to survive the procedure. ↩︎

If you are a print subscriber of the European Review of Books and have received a version of Issue Seven where some pages of this essay are misprinted, please contact us at: info@europeanreviewofbooks.com.