An iron curtain makes a powerful canvas.

Photo by Falk Wenzel

The best iron curtains are the non-metaphorical ones: the massive fire-proof walls that could be lowered onto a theater’s stage in case of disaster. First installed in the Drury Lane Theater in London in 1794, eiserne Vorhänge were standard practice by the end of the nineteenth century, and a standard geopolitical metaphor by the twentieth.

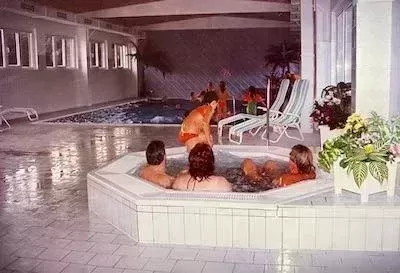

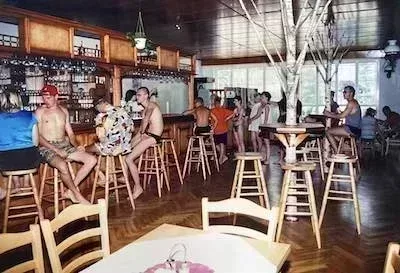

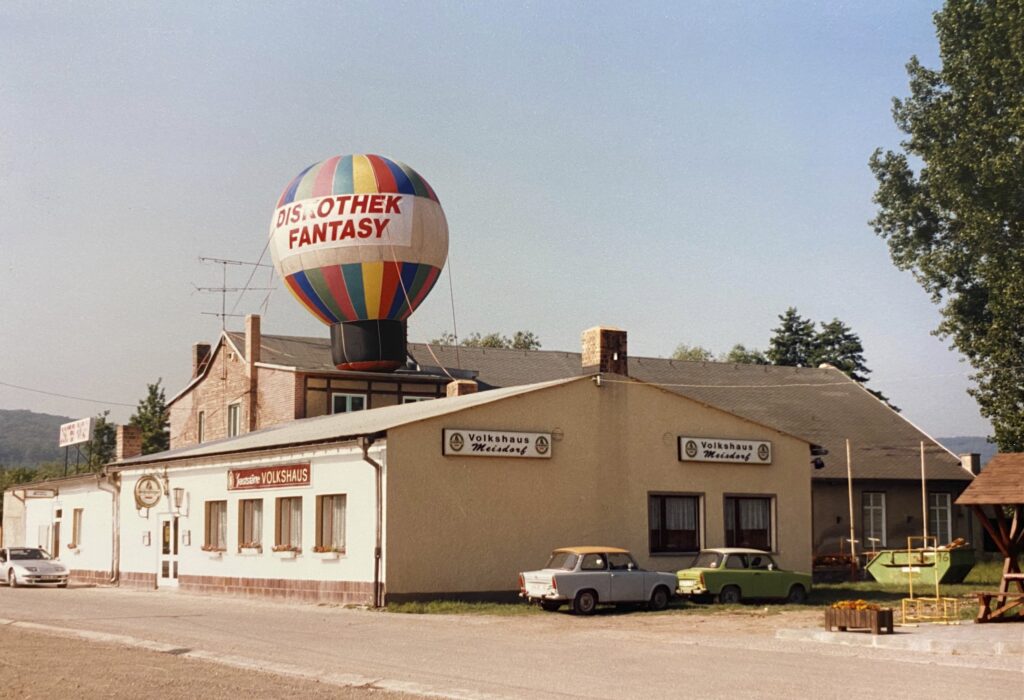

We present here, in front of and behind the ERB’s paper curtain, a selection of photos from a massive project: Aus Sicht des Archivs, by the artists Sven Johne and Falk Haberkorn. From six city archives of industrial cities in Saxony-Anhalt, they gathered thousands of photos that document life in the former East Germany in the 1990s, after the geopolitical iron curtain’s opening.

SVEN JOHNE & FALK HABERKORN

From Aus Sicht des Archivs

Images copyright Sven Johne and Falk Haberkorn

I went to Bitterfeld, a town north of Leipzig, for the first OSTEN festival in the summer of 2022, a three-week-long gathering of art and theater that took place in and around Bitterfeld’s old Kulturpalast. The festival’s opening ceremony gathered us all backstage, « behind » the iron curtain. When, at the climactic moment, the curtain lifted, the crowd applauded, both from instinct and from the specific rush of it.

The Kulturpalast’s majestic old theater came into view: rows and rows of empty red velvet chairs, looking back at us from another era. The Kulturpalast itself opened in 1954 and stands today as a grand relic of the « Bitterfelder Weg », the German Democratic Republic’s cultural policy, propounded there in 1959. Its cajoling slogan feels quaint now: « Greif zur Feder, Kumpel! Die sozialistische deutsche Nationalkultur braucht dich! » (Grab your quill, buddy! Socialist German culture needs you!) The OSTEN festival commandeered the building and filled it with art: experimental, interactive, friendly, loud. You’d enter the building via a wooden ramp — pointedly unpolished, temporary-seeming but remarkably sturdy — that led up to a second-floor window. You’d grab a wheelbarrow and push it up, moving tree-branches aside, and then move circuitously through the Kulturpalast’s various chambers, picking things up along the way. It was an homage, of sorts, to the local workers from the now long-shuttered chemical factories who built the building in their off-hours.

SVEN JOHNE & FALK HABERKORN

From Aus Sicht des Archivs

Wheelbarrows are remarkably agile; why not lug one through an exhibition? Tip it on its side and it becomes a surprisingly comfortable chair. When you were done you’d wheel it out onto the grand front balcony, looking over the postindustrial void, and send it down to the ground via what can only be called a wheelbarrow roller coaster: two metal rails on another wooden scaffold, curving around the building. Wheelbarrows careened down the rails and bounced, cartoonish, on the fine gravel. The exhibition was delightfully clangy, as if to pull a smile from the stern bas-relief visage of Wilhelm Pieck, president of the GDR from 1949 to 1960. There are many ways to pick up a quill.

It’s possible you « had to be there. » The same could be said of the GDR. An iron curtain makes a powerful canvas, too. These archival photographs were projected grandly onto the mammoth iron curtain’s « front ». From « behind » it, with your wheelbarrow, you’d open a heavy door to step through the eiserner Vorhang, only to find yourself suddenly on stage. It was oddly moving, then, to sit in the theater and watch other visitors stumble through the proscenium into history’s blinding glare. Participatory art means seeing other people participate in art.

SVEN JOHNE & FALK HABERKORN

From Aus Sicht des Archivs

The « post » makes « postindustrial » sound temporal as much as spatial; or it elevates a policy into a social or aesthetic condition. In the theater, a child’s voice could be heard over the speakers: Sven Johne’s twelve-year-old son, narrating the region’s history — the « Strukturwandel » and the « Abriss, Arbeitslosigkeit und Abwanderung » (demolition, unemployment and emigration) that it wrought. A third of the population of Sachsen-Anhalt has left since 1990. But the photographs reveal other angles on Europe’s grandest deindustrialization, off the « postindustrial » path. They show nature, commerce, folk festivals. As the artists put it: « es sind Bilder, die gerade nicht den Abriss zeigen. »

SVEN JOHNE & FALK HABERKORN

From Aus Sicht des Archivs

Back to the present. « Alles wird gut gegangen sein werden. » It’s the title track of an album by the German band Brigade Futur 3, the cover of which has the band standing in front of Jean-Pierre Houël’s Storming of The Bastille. Brigade Futur 3 crowded onto OSTEN’s wooden stage, most of them in blue work-uniforms decorated with fluorescent orange safety-tape in various shapes. « Futur 3 » is a grammatical joke, Futur 1 being the future tense and Futur 2 the future-perfect. And Futur 3? That grammatical tense can only be accessed via Brecht-and-Weill-ish cabaret chansons and electric headbanger jazz. Somehow it works! They closed the set with their title track, and the crowd sang along: « Alles, wirklich alles, wird gut gegangen sein ». It doesn’t mean everything will be okay; it means everything will have gone okay. It’s a fine but fundamental distinction. Revolution needs the promise of relief, too.