Ariane, a Young Russian Girl

Claude Anet

translated by Mitchell Abidor (New York Review of Books, 2023)

Insofar as erotica can ever be about something, what is Russia-themed erotica about?

‘Big beautiful chest, spherical tits.’

Does someone know what epithets are suitable for this case?

This question, originally posed in Russian on an internet forum for lovers and learners of the French language, attracts many benevolent francophones. « Gros lolos », they suggest. « Nibards », « melons », or « le balcon »: quite architectural, like « rack ». The thread remains open.

How do we find language for what turns us on? Maybe all erotica is a kind of translation, simply for having found expression in the first place. Translating that expression, from Russian to French to English, would then be merely a secondary act. Then again, maybe arousal and language aren’t separate at all. For some writers, some lovers, some readers, the physical and the verbal are the same. With erotica, I’ve found, there’s no way to lose. Best case scenario: you get turned on. Second best: you laugh. Worst case: you wonder why you didn’t get turned on or laugh, and you have a good think.

At first, I’d intended only to think. About all those femme fatales in Bond movies, the Georgian girls on the Beatles’ mi-mi-mi-mi-mi-mind, the internet ads for « Russian women in your area ». Where did all this come from? I set out to discover the history of Russia-themed porn, back to the nineteenth century at least, all those western writers fetishizing women from the Russian empire. Whether ice queens or sex machines, Russian women are touted as eastern philosophers of sexuality. To sleep with them is to unite East and West, to dissolve the mind-body divide, to extinguish the flame of the Enlightenment. In bed with them, you’ll either become a masochist like a Dostoevsky character, or a sadist, like… a Dostoevsky character. Maybe you’ll have the hottest sex of your life, or maybe you’ll get frostbite on your dick. Russia is a sexual bog without a foothold, and few can resist jumping in. Audre Lorde, for one, had a dream about sex in the Moscow central department store.

eggplant, dart, pintle

And so I thought, strange to say, that if I looked hard enough at the butts of white women in erotica, I could learn something important about global whiteness. I still think so. But as I read about Russian girls — which, it turns out, is how many Western writers refer to women from the Caucasus, Poland or Ukraine (itself disconcerting, two years into Russia’s invasion of Ukraine) — I was surprised by how often my critical frown fell away. Words for « penis » proliferate, each sillier than the last: eggplant, dart, pintle. The men I’m reading love the word « poke » (noun and verb). I realized that a totally serious reading of erotica cannot sustain itself for long: the question is not whether you’ll feel pleasure, but what sort of pleasure you’ll feel.

Some of the pleasure of Claude Anet’s Ariane, a Young Russian Girl, published in 1920 and newly translated from the French into English by Mitchell Abidor, is its fawning descriptions of Ariane’s beauty. Clearly, the author is hot for his heroine. And isn’t that what makes a good novel? Although I hate adventure novels and, incidentally, the ocean, I love Moby-Dick for its monomaniacal whale-on-the-brain (sometimes whalebrain- on-the-brain) narrator. Most authors are aroused by their subjects, in the broadest sense of that term. And, as with Moby-Dick, some of the pleasure in Ariane comes from laughing at the absurdities of the author’s arousal. His Russian-manic-pixie-dream-girl fetish is less lewd than ludicrous. After dismissing one of her admirers, Anet writes, « the young girl shrugged and did a pirouette ».

Claude Anet was the penname of Jean Schopfer, who, among other exploits, played tennis professionally in France and collected Persian artifacts on his journeys through the Middle East. In 1919, reporting on the revolution in Russia, Schopfer was detained by the Bolsheviks in the northern city of Arkhangelsk, where he finished Ariane. It was his first novel. Set in the last days of Romanov rule, the novel opens as a bright morning dawns in a southern Russian province. By nightfall, the teenaged Ariane has received five declarations of love from five different men. A young cadet! Her teacher! Her aunt’s lover! Ariane shoots them down deftly, like a star police academy student at the gun range, placating some and devastating others.

Once Ariane moves to Moscow, she exchanges her « mass of slaves » for one particular lover, a worldly Russian businessman named Constantine Michel. Anet has this Russian character articulate a westerner’s fixation on Ariane’s exotic beauty: Constantine senses in her « the inexhaustible riches of the Russian nature, the gift, the generosity, and the lavish giving of the self that compose it. » But like most exoticized women, Ariane is titillating and disturbing in equal measure. « Ariane, Ariane, … You’re nothing bsut a little Cossack, » Constantine chides, comparing her to a Ukrainian warrior. « You express with simplicity things that a Western woman would die rather than admit … this harsh honesty has its price. » It’s true: Ariane shamelessly recalls previous sexual escapades, even, in a frightening crescendo, kicking off that perilous numbers game: « How many have you had? »

Is it erotica? Is it good erotica?

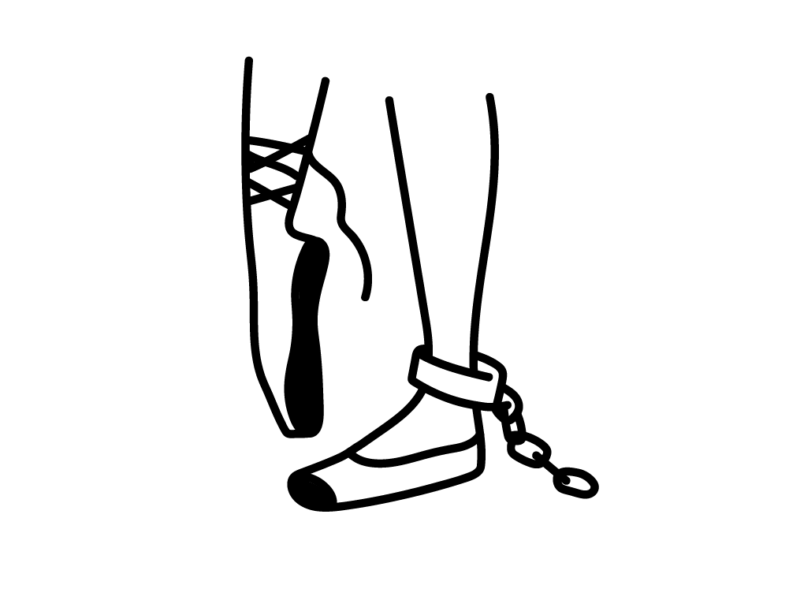

Ariane is a heterosexual fantasia: men and women are doomed to hurl themselves at each other, back and forth, fighting and fucking ad infinitum. And this pendulous (Aha! Here’s a suitable epithet for my internet forum comrade!) narrative makes for a good novel. Is it erotica? Is it good erotica? Maybe it’s literary fiction with a few tasteful sex scenes. Too smooth, too articulate to achieve what William Gass, in On Being Blue, called « the forgetting within the fuck » that makes good erotic literature1. Instead, Anet celebrates the ambient eros of Russianness, and meditates on love as a form of slavery — all without a direct mention of the hero’s pintle. As Ariane and Constantine carry on their affair — in a fancy Moscow hotel, then on a beach in Crimea — they vie for emotional supremacy, determined to prove that they are not in love, and therefore perfectly free. Hot in bed, ice-cold everywhere else: a tried-andtrue thermal metaphor for Russian women’s sexuality.

A few years after Ariane, Anet published Love in Russia, a collection of short stories preceded by what we might call a theoretical introduction, positing a uniquely Russian logic of sexuality. European women act coy, Anet writes, but « Russian women start by giving themselves. » He imagines them asking: « Why make the donation of your body such a valuable thing? Is a man who owns your body your master? Did you give him everything by falling into his arms? Is there nothing that you put above the trade of the flesh? » One story from the collection centers on Nadia, a Siberian prostitute in Tbilisi whose French client laments that, though they spent many pleasant weeks together, « she remained cold as the snows of her native land ». It’s that old western obsession with the Russian « soul », now X-rated. So deep is the Russian soul that the body, even the heavily policed female body, becomes a trifle. That’s the story, anyway.

Ariane could be read as a work of modernism, or even French autofiction — a precursor to Annie Ernaux’s tales of her Russian lover. But it’s also a literary twist on a dirtier canon, one that began well before the October Revolution. The icy femme fatale of the twentieth century is descended from another type: the nineteenth-century « white slave ». Allow me to introduce the champion of this genre, another Russophile adventurer: C.F. Henningsen, a revolution-hopping Belgian mercenary with a fetish for Russian serfs, and surely one of the most destructive of the nineteenth century’s Byron wannabes. Born in Brussels in 1815 to an Irish heiress and a Dane, Henningsen fought in Spain, enlisted with the Russian army in Circassia, led the United States army in Nicaragua (where he set the capital city on fire), married the niece of a Georgia senator, and fought for the Confederacy. Somewhere along the way, in 1845, he wrote a novel about the modern subject who had, in his view, the most pitiable condition in the world: The White Slave; or, The Russian Peasant Girl.

In the early nineteenth century, as European capitals were buzzing with debate on the abolition of chattel slavery, Russian serfdom became a favorite limit case. For proponents of slavery, Russian « enlightened seigneurialism » was proof of slavery’s universalism, its inevitability. For abolitionists, it was the sin made more grotesque: white people enslaving other white people. Henningsen, in a sober introduction to his melodrama, announced that his high purpose, even « whilst amusing » his readers, was « to popularize some knowledge of the condition of the Russian Serf among a people who sacrificed twenty millions sterling to the enfranchisement of its own Colonial blacks. » To his mind, British debates on the abolition of chattel slavery — a stuttering process that extended beyond the 1833 Act — ignored the more significant travesty of the millions enserfed further east. « Nicholas is the greatest slave proprietor in the world, » he writes of the Russian Tsar. « But these are white slaves, not black. »

As far as I can tell, the term « white slavery » has always implied sexual exploitation. In 1803, the Irish traveler Martha Wilmot, a friend of a friend of Catherine the Great, was curious to visit a particular Russian nobleman’s « Tartar retreat », a windowless suite in his house « inhabited by fair Dulcineas » or, less euphemistically, kidnapped women. Curiously, by calling his sex dungeon a « Tartar retreat », the nobleman figures it as an Orientalist novelty rather than a Russian one. It’s all the same for Wilmot. Russia, in her account, is hardly Western: it’s a place where white women are violated.

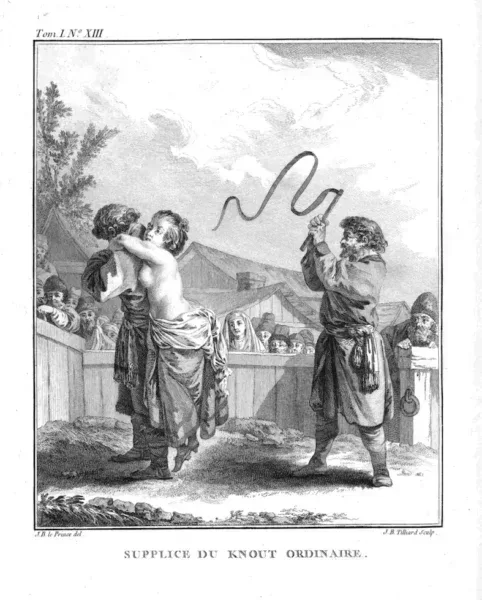

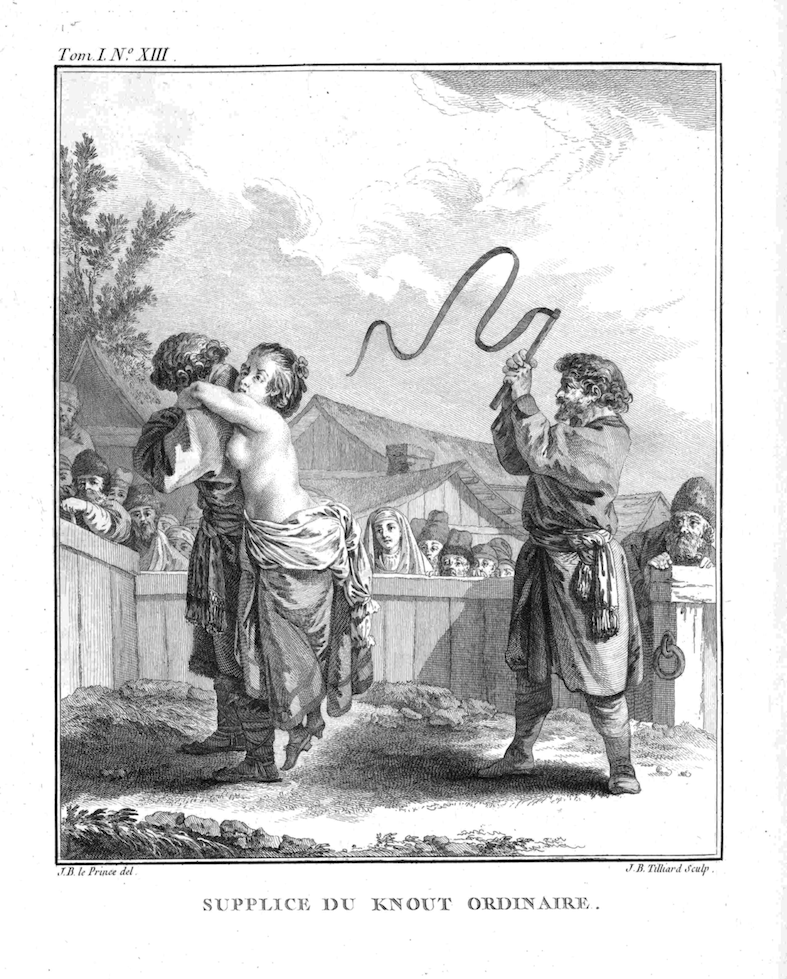

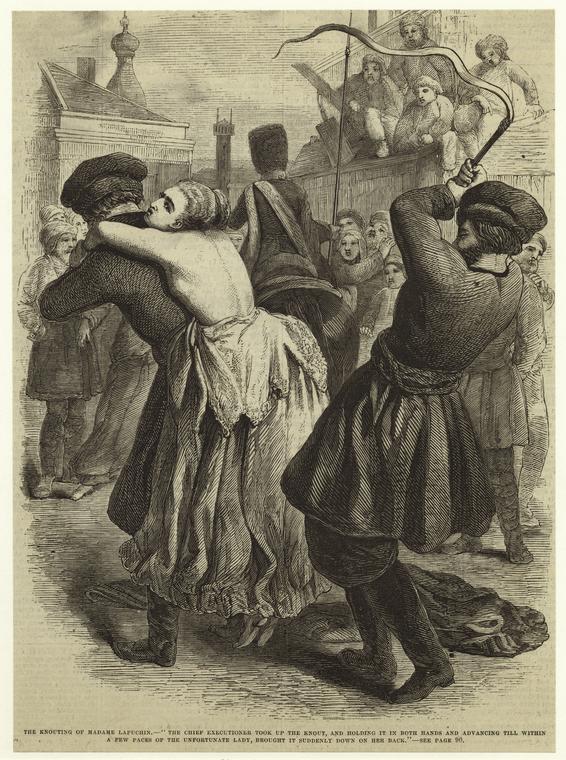

Knouting Mme Lapuchin

…in 1743, Empress Elizabeth had the noblewoman Natalia Lopakhina publicly whipped for political conspiracy. A 1766 engraving by a Frenchman relayed this political episode to the west without any sex appeal. But in 1845, the French engraver Charles-Michel Geoffroy rectified this oversight with his image of « the beautiful Madame Lapuchin » getting « knouted »…

Or it’s a place where they’re whipped. Here’s another curiosity: in 1743, Empress Elizabeth had the noblewoman Natalia Lopakhina publicly whipped for political conspiracy. A 1766 engraving by a Frenchman relayed this political episode to the west without any sex appeal. But in 1845, the same year that The White Slave came out, the French engraver Charles-Michel Geoffroy rectified this oversight with his image of « the beautiful Madame Lapuchin » getting « knouted » (the English term « knout » comes from the Russian word « knut »). A white woman clasps her arms around the neck of a man facing away from her, as another man wields a knout in the air, and she looks back in fear. Her exposed white back draws the eye. Geoffroy also takes care to carve in some — if you’ll excuse my noughty tabloid speak — sideboob. Geoffrey’s engraving is emblematic of this « white slavery » furor: a nexus of moral outrage and sexual titillation. And it’s proved a timeless pornographic image: Madame Lipuchin has graced the cover of Rev. Cooper’s Flagellation & the Flagellants: A History of the Rod in All Countries from the earliest period to the present time in 1869 and the inside cover of William Cooper’s 1988 An Illustrated History of the Rod. Today you can find her on spankingart.org.

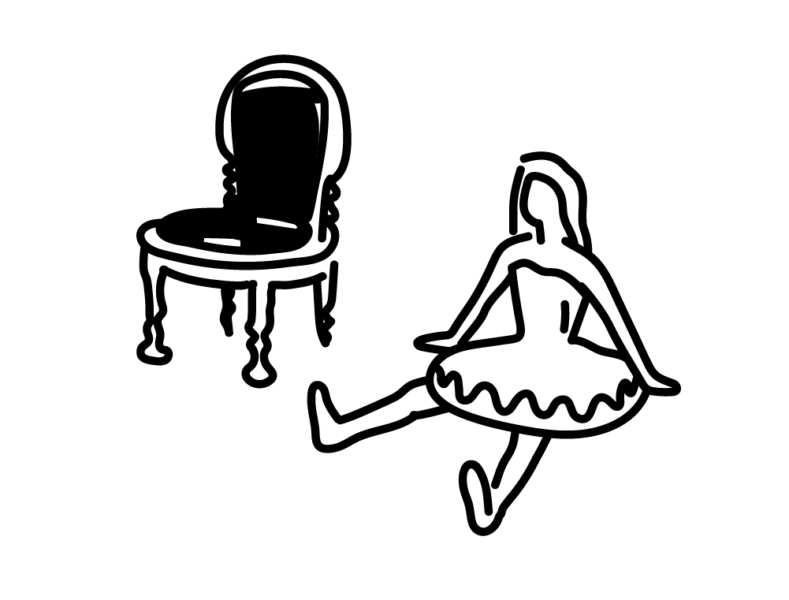

Imperial Russia, in other words, has a special place in the global BDSM imaginary. Historically, this makes sense. Russian noblemen were known to rape their female serfs; scratch most classic Russian writers and you’ll find an anxious droit de seigneur story. Leo Tolstoy and Ivan Turgenev raped many of the peasants on their lands, siring children they didn’t recognize or support. According to lore, one nobleman sent all his peasant men off to military service so he could rape his female serfs and repopulate his lands with his own biological children. Other noblemen made their serfs perform plays and operas; one spectator of Nikolai Sheremetev’s famous « serf theater » noted that, « the actresses and the ballerinas are practically the same as the bench on which the count sits while watching the performances … that is, his property, and so must they also please him in another way in those instances when one of them strikes his fancy. » 2

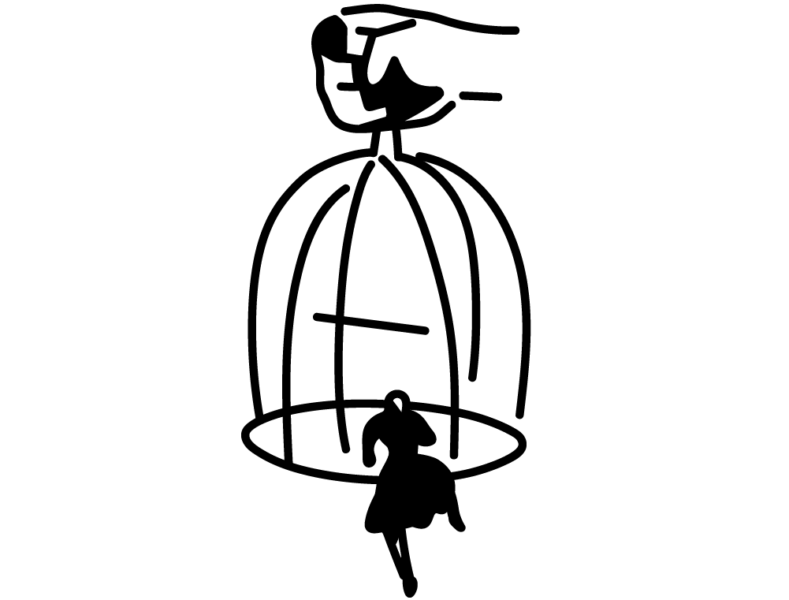

Henningsen’s The White Slave is nestled in this web of myth and reality, moral outrage and titillation. His heroine is the beautiful serf Nadeshta, and his rather autobiographical hero is Horace, an Englishman in Russia. While visiting a gentry household, Horace is taken by a portrait of a mysterious woman: « Her complexion, features, and figure, were rather the type and ideal of the Polish than of the Teutonic stamp of beauty. Her ‘Asiatic eye’ was quite Polish with its mingled softness and brilliancy ». It is Nadeshta, outfitted like a lady. An uncommonly beautiful girl, she caught the attention of her landlord, who privileged her with an education and had her sit for this portrait but did not emancipate her. « Oh, cruel benefactor! » Henningsen’s narrator exclaims, « why take Nadeshta like a cagebred bird, and show her the wild woods and the free meadows, and the glorious skies, and then forget to untie the string which binds her fluttering to her cage for ever, hopeless and alone? » Once her master dies, Nadeshta is prey to the advances of his evil son, Prince Isakov.

It’s unclear what Horace (or Henningsen, for that matter) thinks « Russian » means in the first place. Nadeshta is a confusing scramble of Russian, Polish and Asian. Is Russian a mixture of European and Asian? Or not an ethnicity at all, but a political designation? Maybe to be Russian, for Henningsen, is simply to be white and enslaved? Nadeshta’s beauty, though, makes her an exception. With the authority of the eyewitness, Henningsen notes that Russian serf girls are, in general, quite ugly: « hideous », « misshapen », raised « like exotics, to premature womanhood ». And he emphasizes their ugliness with recourse to tropes of Black women’s physicality. « It is a very common sight », Henningsen writes, « to see a matron throwing her breasts over her shoulders, to suckle the child she carries on her back. » In Henningsen’s writing, Russian women’s association with enslavement seems to corrupt their whiteness. And so his novel stages, in effect, the whitening of a white slave.

The White Slave’s other heroine, a proud young Englishwoman, aptly named Blanche, marries a mysterious man who turns out to be a runaway Russian serf (and Nadeshta’s brother). He insists, in melodramatic doom-risking fashion, that they return to his home country. They are captured, of course, by the very same Prince Isakov, whereupon Blanche becomes almost as aggrieved at Russian tyranny as Henningsen. « I am Blanche Mortimer », she exclaims, « I am not your slave! » « Nay, there my indignant beauty, » replies the Prince, « you are in error; by the Russian law, if a free woman marries my slave, she too becomes a slave, and you are mine. » « I! » she says, « good God! » And faints. The plot resolves into a parable of free West and unfree East. In Russia, readers of The White Slave are led to believe, even a white Englishwoman can be enslaved and reduced to inhumanity. Once enserfed, Blanche transforms into a haggard Russian peasant woman who wanders, mad, through a winter hellscape with her dying infant in her arms. This once haughty girl is, in her Russification, reduced to — you guessed it! — fighting a wolf. Beautiful Russian women, meanwhile, deserve to be saved from Russian barbarism — by western men. By novel’s end, Horace has stolen Nadeshta from Prince Isakov and whisked her away to England, where he’ll make a lady out of her.

« White slavery » was a gratifying moral melodrama for enlightened Europeans of the nineteenth century. But by the twentieth century, and especially in Cold War USA, the « white slave » would beget some genuinely rollicking stories. The iconic title of Russia-themed erotica is Grushenka, or Three Times a Woman. First published clandestinely in Paris in 1930, the novel is now attributed the Ukrainian-born novelist (and eventually Hollywood horror writer) Val Lewton. In Grushenka, eighteenth-century Russia is a utopia where « the elegant women liked to show their breasts with the nipples sticking out above their dresses » and « lady’s love was an art practiced with great finesse in the harems ». Lewton’s dirty novel begins with an evil noblewoman buying an unusually beautiful serf. Grushenka is raped, whipped, and exposed to all manner of torments. As she’s sold to various people, she becomes a virtuosic lover and, in a classic whore-to-madam plot, even succeeds in owning her own retinue of serf girls. (One online reviewer — this book has been republished countless times — notes with disappointment that the novel is not fanfic about Dostoevsky’s sultry heroine in The Brothers Karamazov. He’s not off the mark: in 1958, the director Richard Brooks was adapting The Brothers Karamazov for the screen and wanted, for the role of Grushenka, none other than Marilyn Monroe. It didn’t work out — but can you imagine?)

Los Angeles was also the center of erotica publishing and, in the 1960s, the crème de la crème was Holloway House. In 1966, they republished Grushenka with a new intro by Paul Gillette, Ph.D., a connoisseur of fine wines and cheap erotica. But it was the Cold War, after all, and Gillette discerned a political message beyond the kink. « In Grushenka, » he wrote, « sexual description serves a larger purpose: it demonstrates the inhumanity of a serf-holding political system. » He’s right, I guess: the novel does demonstrate the inhumanity, but only because that inhumanity happens to be titillating. In Grushenka, serfdom provides an endless supply of beautiful white women at no cost — it makes prostitution moot. One character in the novel, a Russian nobleman, « during his trips to Western Europe, had learned that there were harlots whom one could buy for an hour or a day. He even brought to Russia with him some wenches who did a nice job in bed. » But these European prostitutes « seemed money wasted, however, because his own slave girls could do as well and even better. They were harder, had no moods and were easily put in their places when they did not behave properly. » Grushenka affords readers the pleasure of identifying with the Russian nobleman, who « never thought of a woman as a human being, but as his property. »

Erotica is world history written onto the two hemispheres of a woman’s butt.

The Russian woman is only one historically particular kind of « white slave »; the kink has proven adaptable to other historical settings. Holloway House’s 1966 catalogue, while we’re at it, included another tale of white womanhood in peril: The Memoirs of Dolly Morton, originally written in 1899 by the French erotica writer Georges Joseph Grassal. His heroine, Dolly, is a white Philadelphia girl who moves to Virginia to run an underground railroad station before the American Civil War. (Grassal wrote under the very appropriate penname « Hugues Rebell ».) Paul Gillette, the erotica sommelier, introduced this title as « A Moll Flanders with a message, as it were, and a sexy Uncle Tom’s Cabin. » Dolly is kidnapped (in the novel’s parlance, « enslaved ») and kept as a mistress by a Southern planter named Randolph. At one point, a white lynch mob captures Dolly, one of them saying: « I’ll rule a dozen lines across her bottom that’ll make it look like the American flag, striped red and white. » I paused here, bewildered at a French guy imagining an antebellum Southerner wanting to whip the US flag (not the Confederate flag but the Union flag, no less) onto a white woman’s butt. The anonymously authored introduction from 1889 explains the appeal: « our eyes are shocked, and, by an inevitable natural impulse, delighted at the sight of the white, well-developed hemispheres laid bare and blushing to our gaze, only to receive the cruel lash. Sorry are we, but little can we do ».

Erotica is so often about racial fetishes, even when it appears not to be — even, that is, when it’s about white women. « There is no ‘raceless’ course of desire, » as Sharon Patricia Holland has put it.3 And this « white slave » subgenre certainly does chart unexpected courses. Dolly becomes « eastern » when the Black enslaved women in Randolph’s house prepare her, « like a Turkish lady of the harem », for her first night with him. For Randolph, meanwhile, the appeal of the kidnapping is the chance to treat this white woman « as if » she were Black: « I am going to whip you as if you were a naughty slave », he says villainously. In Grushenka, as in The White Slave, the bodies of Russian serf girls are described in the language of misogynoir, with « sturdy undercarriages, broad backs, large hips, terribly thick bottoms and legs ». When Grushenka, now a mistress herself, beats a Russian serf girl, the narrator deploys the racist myth that dark-skinned people feel less pain: « She certainly did not feel it much. She had a tough, brown skin and the hard flesh of her peasant stock. » In these novels, when white women’s sexual practices contravene bourgeois ideals, the characters are often re-racialized, described as non-white. So if Russia-themed erotica tends to be about sexual slavery and sexual freedom, then — as in the construction of race itself — it’s always in reference to others: other white women, middle eastern women, Black women. As a novel in this messy canon, Ariane is about all of these figures, about the history of racialization across the globe. Erotica is world history written onto the two hemispheres of a woman’s butt.

I read Ariane, a Young Russian Girl in one sitting. Abidor’s careful, languid English sentences captured my attention. His translation is way smoother, way sexier, than the lovers he describes: the syntax gets taut, then flows loosely again, in a pattern that moves the novel forward and back like waves. As for Anet himself, he failed to arouse me with his heroine’s antagonistic iciness, or to convince me that love is war. Instead, he reminded me that our sexual imaginations are as historical and political as any war. Ariane is just one in a long line of « young Russian girls », and to be turned on by her is to join the ranks of Henningsen and Gilette. No pleasure — sexual, writerly, readerly — is innocent. But when we imagine « innocent pleasures », I think, we’re fantasizing about a desire beyond history, beyond ourselves. And what fun, or what good, is that? To read erotica — to desire anything at all, really — it’s best to keep one eye open, and one eye closed. In other words, you have to wink.