From the office of the future to the office of the past. What endures?

In 70 years, the

average dimensions

of a desk have

changed four

centimeters.

Q&A with Stephen

Petermann

STEPHAN PETERMANN, SANDER PLEIJ

A desk is a desk a desk

Stephan Petermann is co-author, with Ruth Baumeister and Marieke van den Heuvel, of Back to the office: 50 revolutionary office buildings and how they sustained. He is an architect/historian who has participated in many OMA/AMO projects and books. He is also the Editor-in-Chief of VOLUME.

What is this new religion of work? I am overwhelmed all day with messages about how to work and concentrate better.

The position and function of work, and therefore the workplace, indeed have very religious aspects that go beyond the mere spiritual. We derive a substantial part of our meaning from our work life. As in: we think the workplace should reflect our body (seating, materials), our moral virtues (fun, no pain) and our relationships (communal versus individual). The religious is reflected in the architecture: the cell-based office was derived from the structures of European monasteries, which in turn were derived from the even older Roman cella. Meeting rooms could be considered a hybridization of the tavern and the chapel. Lastly, we find prophets declaring new workspaces every few years or so. We call them office consultants.

How much of the office-of-the-future prophesying emerges from paid consultants? (Leading question.)

The money flows on many obvious levels: from the owners of the real estate, to the operators, the furniture specialists, the IT developers, etc. They are key drivers behind promoting change, because change means turnover. Creating instability is a core element of selling consultancy as a service. And not surprisingly we often find change for the sake of change. In 70 years, the average dimensions of a desk have changed four centimeters. Interestingly, we also find that the predicted gradual rate of value depreciation used for tax systems in the office buildings we looked at doesn’t really hold. In fact, a considerable amount of the office property we looked at is worth more now than it was at construction. It’s a process known to most owners of property, but it is not reflected in taxation or in property development. One key finding of the book is that we should abandon the idea that office buildings have a supposed lifespan of 50 years.

I bet there is a lot of money earned with the predicate «sustainability».

Regarding sustainability the water is unclear. Yes, upgrades are made to buildings for increasing their energy efficiency. But the key engine in office design — promoting change — is, de facto, never sustainable. There is a push to make this process circular, also to promote, for instance, the use of biobased materials, which is good but misses the point: not changing is — when not unavoidable — always best. But there isn’t a good story or business model in not changing. You are not going to pay me to just say: ahh leave everything as it is.

So, are these well-known offices that you researched sustainable?

It’s a mixed bag. Some remain remarkably pristine over time, like the Aarhus City Hall by Arne Jacobsen or the Kagawa Prefecture hall by Kenzo Tange, which you can consider to have achieved a form of sustainability. Others, mostly the multi-tenant buildings housing different companies, have a dramatically higher rate of material metabolism. We looked at the interiors of the Seagram building in New York by Ludwig Mies van der Rohe and found more than seven kilometers of plasterboard being used in the building in 25 years of service.

Why did they survive so long?

A considerable number of the buildings we looked at were the result of a shared pursuit of an architect and their client to create something new. This is something that is increasingly rare, now, because ownership positions and corporate roles have changed. Most companies feel less comfortable in expressing their corporation in a unique way. If you work with a talented designer, and give them space, we show that it also pays off. Buildings with character largely last longer.

What makes an office sustainable?

Cleaning is part of it. Cleaning, now seen as an outsourced activity for low-skilled workers, really contributes to the quality over time of a building. There is an interesting correlation that when an office building is designed with care and consideration, employees are more proud, but also cleaners take better care of it. I would propose that cleaners should share in the profit gains in real estate by the owners and that the craft of cleaning is inserted into all school curricula. For me these are all smaller, but crucial elements of a larger consideration on what indeed counts as sustainable.

What office do YOU like best?

Previously in my career working at OMA with Rem Koolhaas, we were both on the lookout for completely miserable working spots: dead meeting rooms with no daylight, horrible hotel lobbies with irritating mood music. The irritation that came from those spaces—such was our idea, anyway—would increase our creative productivity.

As people are returning to their offices, so is the blah-blah-blah about office space optimization. Stripped, rethought, and renewed: the office of the future!

But what can be learned from the office of the past? Stephan Petermann, Ruth Baumeister and Marieke van den Heuvel wondered what endures. They’ve researched landmark office buildings that still function as offices today, studying archival documents, photography past and present, contemporary interviews and criticism, and compiled their findings in their bulky book, Back to the office: 50 revolutionary office buildings and how they sustained. They bring us to four of these locations:

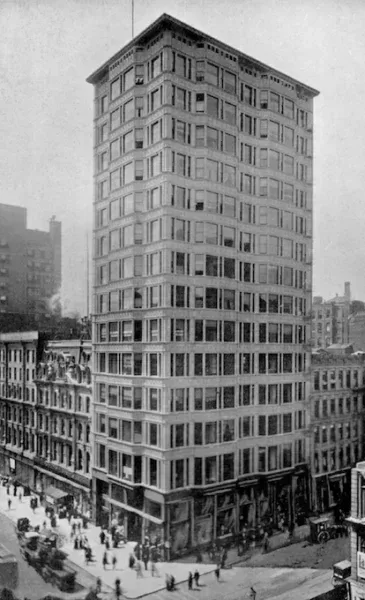

↦ The Reliance Building (Chicago, USA)

↦ Aarhus City Hall (Aarhus, Denmark)

↦ The Shizuoka Press and Broadcasting Center (Tokyo, Japan)

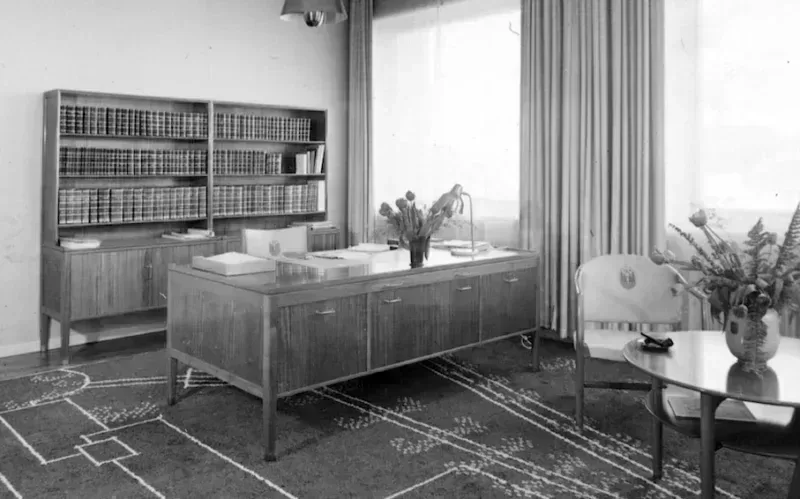

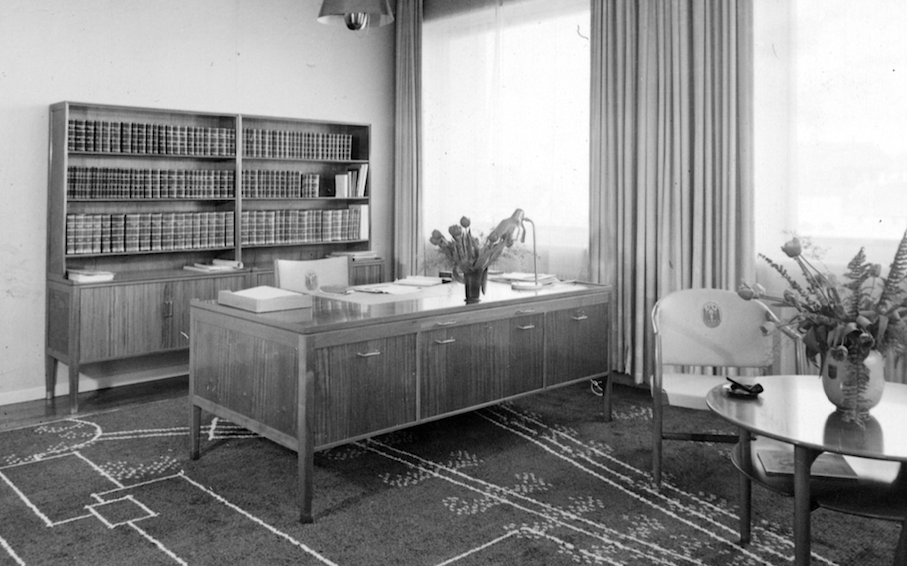

↦ The Van Leer Headquarters (Aalsmeer, Netherlands)

A revolutionary pigeon haven and a Gesamtkunstwerk