A story about the art of disappearance

Before Sara showed me how easy it was to alter documents, I was merely a social worker on probation at the Emergency Shelter for Women in Berlin. I remember the first intake I handled alone: a woman with two plastic bags, no socks, and an expired visa. She handed me a folder fraying at the edges, thick with documents, some printed, some handwritten, most of them creased like she’d slept on them. The woman kept pointing to a page stamped Aussetzung der Abschiebung (Temporary Suspension of Deportation), asking if it was still valid. I told her I didn’t know, even though I did. It wasn’t.

In those first weeks, the hardest part wasn’t the job itself, but the break room. The fluorescent-lit normalcy, my colleagues’ boxed lunches and chatter about their weekends. It all felt like a language I had no access to. There was another language I wanted to be fluent in: the one the residents developed in their distress — their own gestures and codes for surviving a world intent on erasing them.

You’re reading this essay for free. With a membership, you can read the full magazine, and you get access to our fabulous Library.

Here’s our offer: 3 months unlimited digital access + 1 print edition for € 38,00 € 19,00

You’ll get Issue Eleven in print as your first magazine, right to your mailbox.

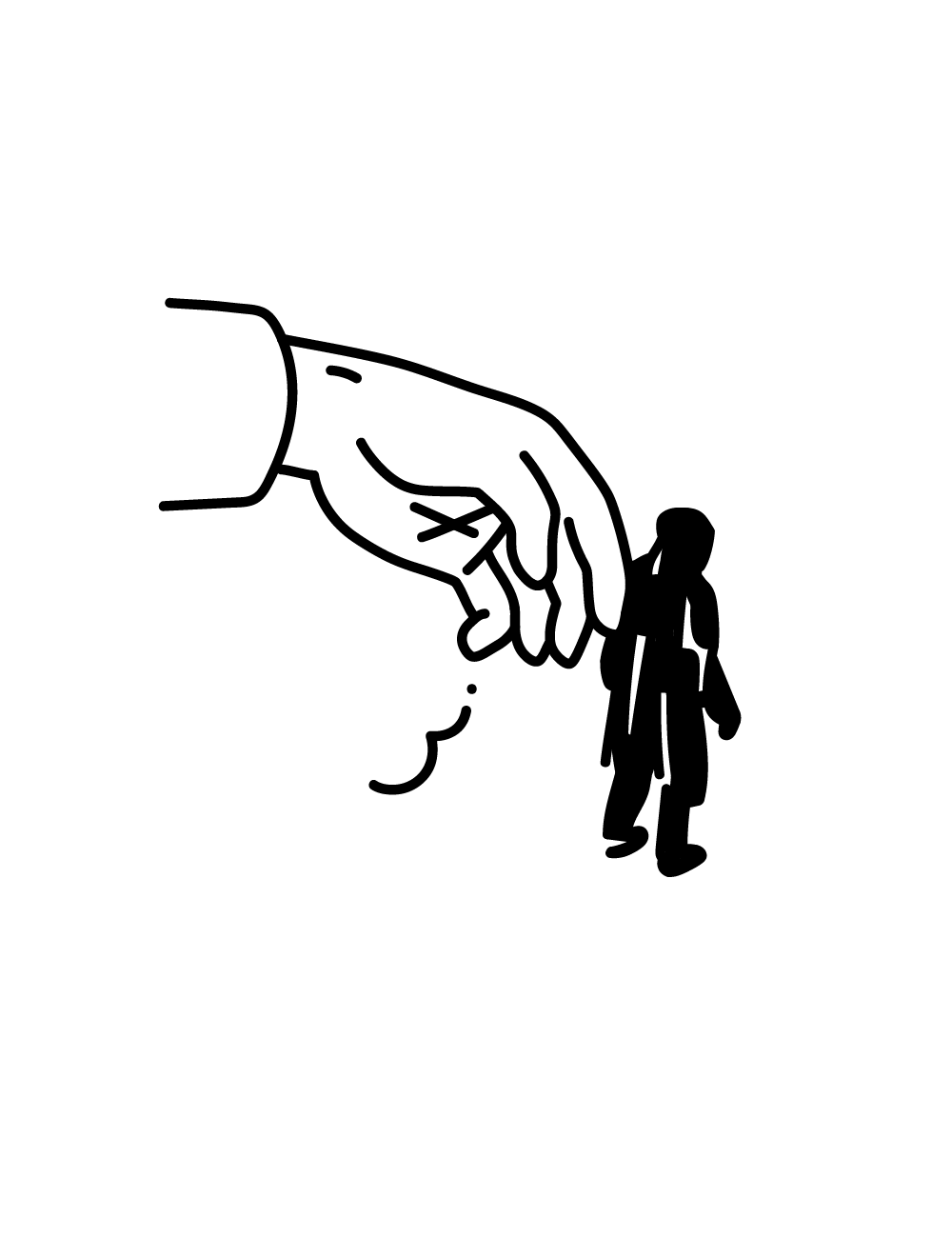

So, my real community was forming among the residents, amidst the chaos, tending to the sporadic stream of crises and makeshift plans. Their hive of constant crisis, with its overlapping traumas and contradictory paperwork, reminded me viscerally of the women from my Turkish childhood, the ones running the textile shops, who had so much potential eclipsed by necessity. For them, work wasn’t a career; it was survival — sweat, debt, uncertainty. Back then, I was powerless to help them. The women in the shelter were living that same truth, just in a different country and under a different system. At this stage of my life, I was filled with a displaced benevolence for every soul who walked through our doors, yet my job was one of cold limitation: filling out the forms that could decide whether or not they disappeared.

Every woman who walked through our doors carried the weight of expired visas, rejected asylum claims, missing work permits. I watched them clutch their folders, knowing that without the right stamp, the right signature, they could vanish back into the shadows. The machinery of bureaucracy hummed in the background, a constant reminder of their precariousness. My one escape from it, and theirs, was the weekly art session I ran — a space where paper was for expression, not evidence. That was where Sara stopped being just another resident and became, simply, Sara. Though nothing about her was simple.

Sara had needle tracks across her arms like constellations. Before the shelter, she had volunteered in refugee camps — when she could keep her addiction hidden. Her law degree from Turkey existed mostly to keep her parents off her back. She’d spent years stitching together the perfect-son costume from guilt and distance.

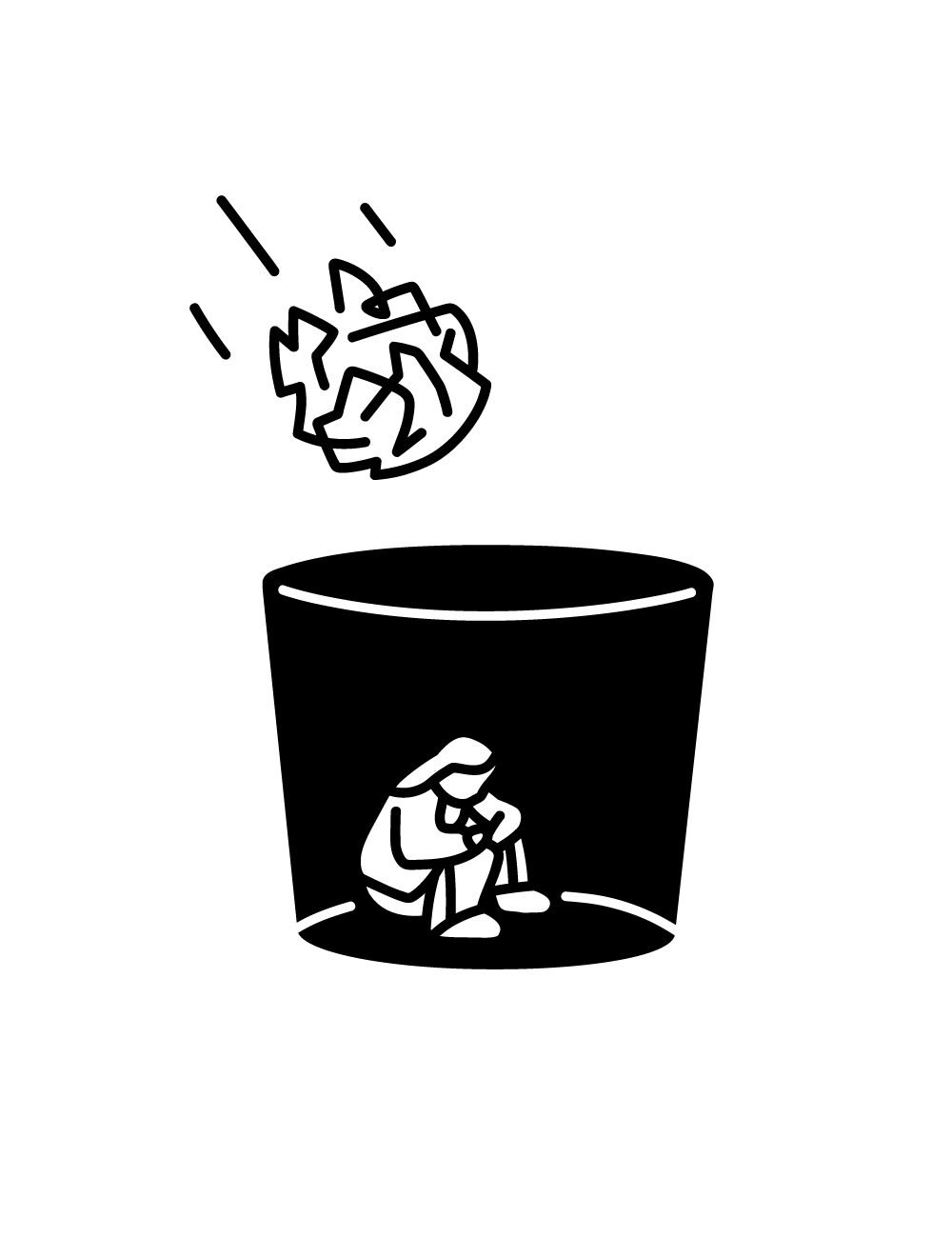

Sara carried her own folder of documents, but unlike the others, she treated the papers with contempt. « Look at this, » she said during one of our first conversations, waving a rejection letter. « They want three more forms to prove I exist. Three more ways to say I’m a legal human. And a couple more to say I’m finally a woman. » She crumpled the letter and tossed it in the bin. « I’d rather forget the whole thing than beg them to recognize me. »

Sara and I sometimes smoked in the shelter’s backyard, watching cranes rearrange the skyline. One of the residents from the second floor shouted in German, « You girls, stop smoking. It all comes into my room. Stinks! » I immediately stubbed out my cigarette with my foot and shouted back, « Sorry. »

Sara didn’t react. « The German language tastes like stale bread, » she said in Turkish, exhaling smoke toward the construction site. « All those precise, flavorless words. How could anyone think that way? »

I giggled. « How could anyone think with genders in a language? I get it all, but not this. I can’t. » Sara let herself laugh. « Hah, that I know well. »

Sara was a gifted painter. During the weekly sessions in the top-floor dining hall, she was always lost in her work. She often kept going past the scheduled time, even as dinner was served at 17:30. She always chose a gray paper and worked only in pencil, sketching female bodies in mythical forms: a horse with a woman’s head, a woman with a horse’s body, and other strange hybrids. Once the page was full, she threw it away. Every time.

« Why don’t you ever keep them? » I asked her.

« Because they’re not real, » she said, not looking up from her sketch. « None of this is real. The drawings. At least when I throw them away, I’m being honest about it. »

Sara was a sex worker who scoffed at those who called themselves « pleasure activists. » She was tough, but never rough. Her voice could tear through a room, and yet she’d still ask if you needed anything, eyes soft in a way that didn’t match her mouth. She loved her job because it gave her power. She hated her customers because they believed they were the ones in control. She liked using what she had, what she’d been given, to survive. Nothing had ever been handed to her, nothing came by luck. But her body, the one thing that was truly hers, worked.

Sara chain-smoked. She sometimes dealt drugs, not to support her own habit, but to send money back to her family in Turkey. For many immigrants, unless they came from wealth, that was the reality: proving they belonged in the German dream. She wasn’t one of the guest workers from the ’60s and ’70s who bought houses and land with their hard-earned halal Deutsche marks. Most people looked at her customers and only saw addicts. Sara saw the blueprint of them. Drawing on her background in law and sociology, and perhaps more profoundly, on an understanding of the fractured selves a person can perform, she could step outside of it and see the architecture of their fall. Or leap.

One break, Sara shared a theory: as society became more obsessed with productivity, so too did its reliance on stimulants. « People don’t take drugs to numb pain, » she said, flicking ash. « That’s the cliché. But it’s wrong. They take them to focus on something. Doesn’t matter if it’s pain or pleasure. They want to focus on it so intensely that everything else disappears. » She pointed a finger to my chest, where she knew I had a black cat tattoo. « Like laser to remove tattoos. You understand? » Her voice shifted, suddenly girlishly high-pitched. She took a long drag. « Documents are drugs too, » she continued. « People get addicted to proving they exist. One more form, one more stamp, one more signature… Maybe this time they’ll believe I’m real, I’m a real woman. »

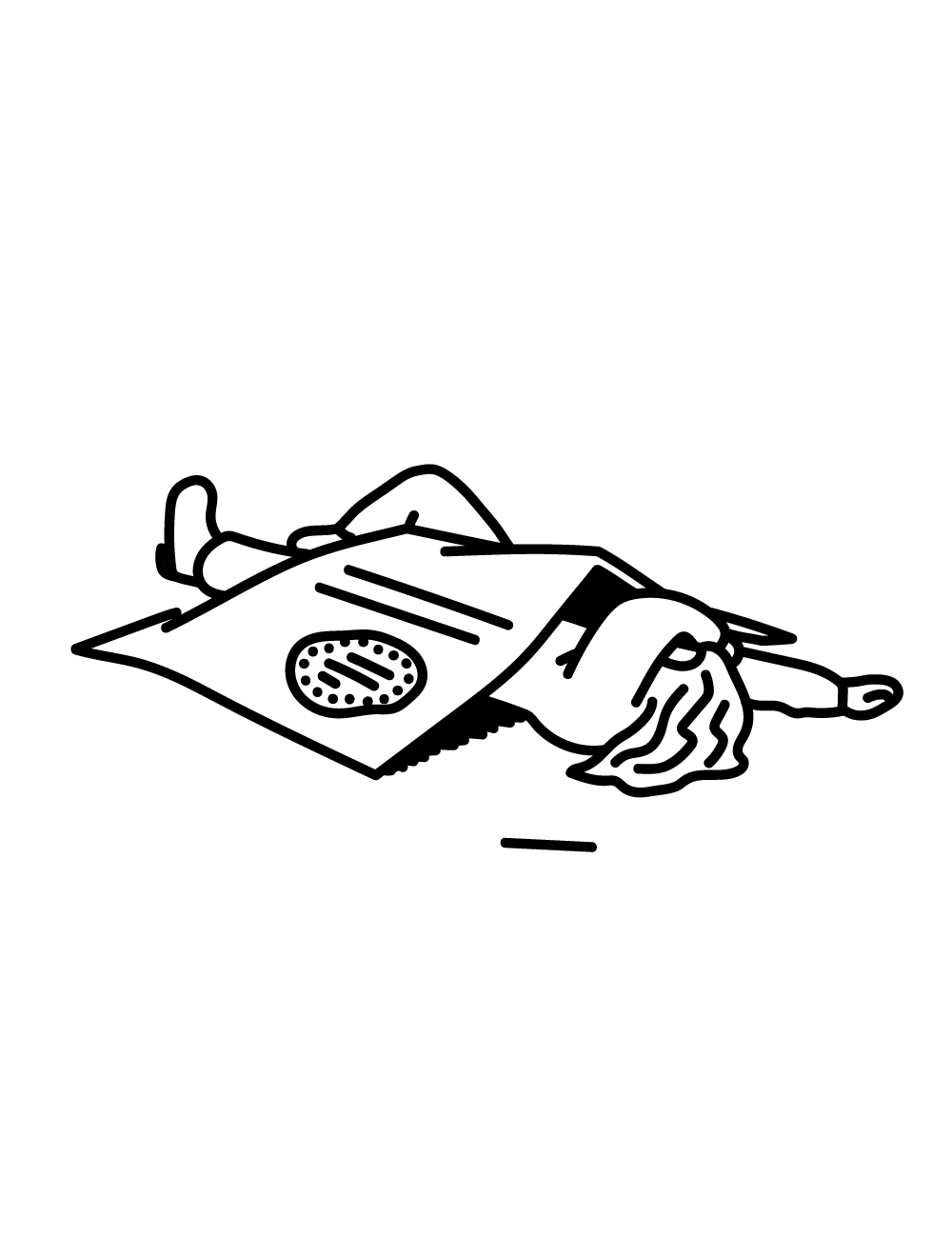

She laughed bitterly. « Look, » she said one evening, spreading her expired residence permit on the reception desk. With a careful hand, she changed a 4 to a 9, extending her legal stay by five years. The alteration was subtle, almost invisible. « Getürkt, » she giggled, sensing my question before it formed on my lips.. « Don’t you know the word? »

« I’ve heard it, but… »

« It means to Turkify. To fake. »

I felt that the word had already become our inside joke. « Aren’t you afraid of getting caught? » I asked.

« What’s the worst that could happen? They deport me? » She shrugged. « They’re going to do that anyway when this expires. At least this way, I buy myself time. »

Then I watched her drifting to the country of herself, meticulously working on the document.

She taught me the techniques during my night shifts; which pens bled the right way, how to steam stamps for reuse, the font styles that government offices preferred. « Call it translation, » she said. « You’re just translating nonsense into something that actually helps people. »

Our shift-based friendship blurred into something less professional when I gave Sara my phone number. « You sure you trust me that much? » she asked, the scent of booze wafting off her. I laughed it off and left. Outside the shelter, we sometimes ran into each other. Our greetings were warm but threaded with a strange awkwardness, both aware of the shift between our private connection and public selves.

The night Sara disappeared, she had been agitated all week. Her latest asylum appeal had been rejected, and her residence permit was set to expire the following week.

« They want me to prove I’m in danger in Turkey, » she had told me. « How can I document fear? » In art class, she had spent the entire session working on a single drawing — not her usual mythical creatures, but a detailed sketch of official documents, forms stacked upon forms, each one stamped with the word REJECTED. For the first time, she didn’t throw it away. « I’m keeping this one, » she said. « Someone should remember. »

You’re reading this essay for free. With a membership, you can read the full magazine, and you get access to our fabulous Library.

Here’s our offer: 3 months unlimited digital access + 1 print edition for € 38,00 € 19,00

You’ll get Issue Eleven in print as your first magazine, right to your mailbox.

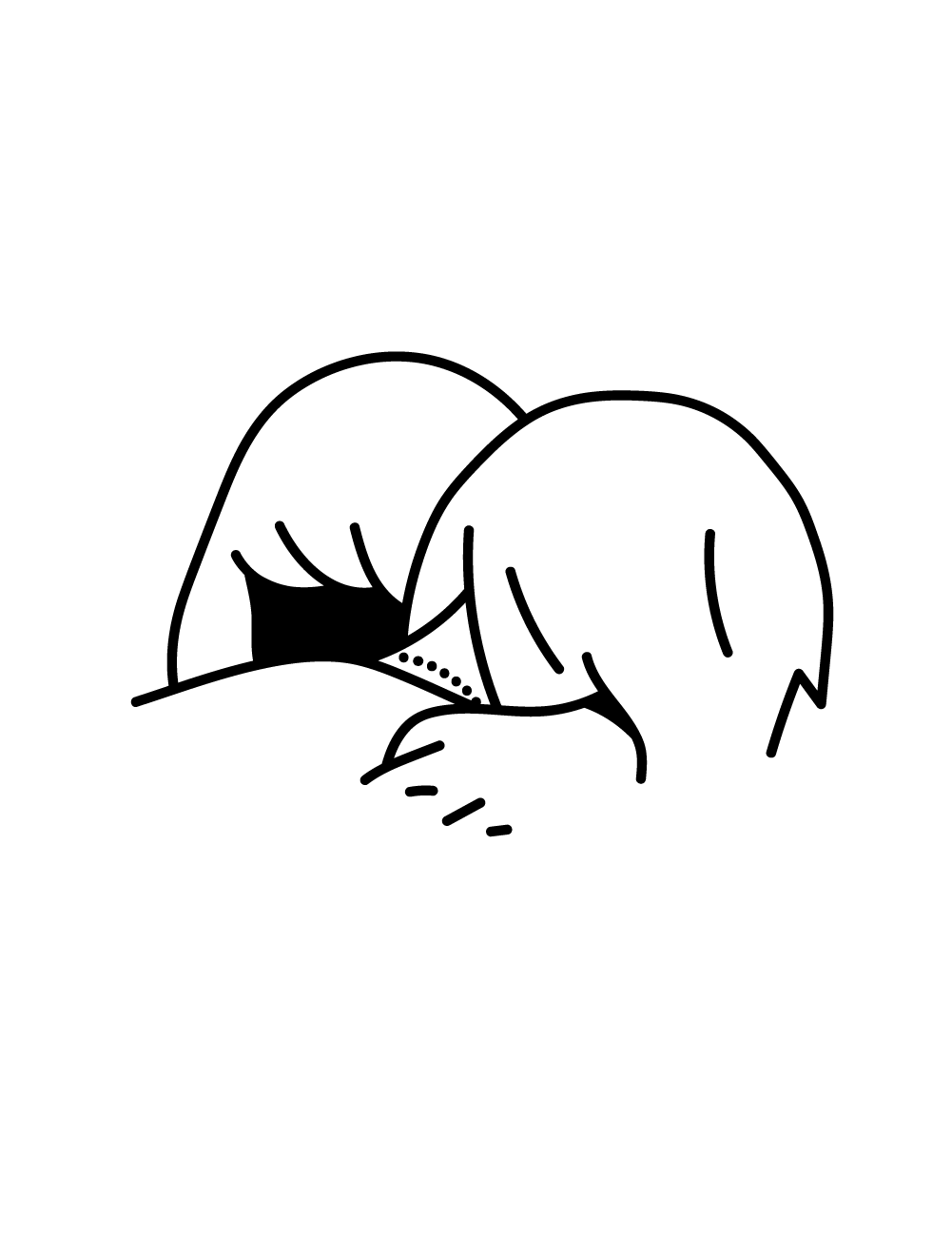

That night, I saw Sara at the bar in one of those cobalt cave clubs. I tapped her on the shoulder. We hugged, at once distant and close. « You’re killing it in those shoes, » I said. She hugged me again, then disappeared into the misty haze of the dance floor. Sara was dancing and hugging a bearded man whose pupils were black pinholes. They clung to each other, like two animals locked in motion, neither moving forward, nor letting go. Nothing spilled. Nothing broke. Just holding. Suspended for minutes. Sara looked like she wanted to hug and be hugged by the whole universe that night.

I thought of that hug for days. The next week Sara didn’t come to the shelter; her online presence shrank to pinpricks. I stayed glued to my phone. Read receipts. Timestamps changed, but no response. The nights at the shelter became long, each minute stretching into an hour. My anxiety festered, a cold knot in my chest. Where was she? Was she okay? The routine of my shifts, once comforting, now felt like a cruel mockery of normalcy. My mind kept replaying her last hug, searching for a clue, a warning I might have missed. By the end of the week, unable to bear the silence, I sat at a computer and typed:

I hope you are all doing well. I’m writing to

express concern about a missing woman. It’s

been five days since she was last seen at Tremor

Club early Saturday morning, November

26th, around 3:00 a.m. She hasn’t been

to any known addresses or contacted

friends since. Name: Sara. Height:

185 cm, slim build, ashy brown hair,

prominent nose. Last seen wearing a

shiny black skirt, white platform shoes, and a

red biker jacket.

I posted the message to every social media channel I had access to. I printed flyers with her description that we posted all over the city — libraries, offices, cafés, which felt like a violation, a complete overexposure. We used a photo taken on a cheap Rossmann disposable during an art session, not the official one from the catalogue. Every time, I apologized to her photo. Police reports and all the tedious wormholes of German bureaucracy. No news, no word. Other women in the shelter suggested we organize a night forest walk to search for her, a proposal which was immediately rejected by the manager who said, « We’re not playing detectives here. This is a serious case. Leave it to the authorities. »

During the long night shifts from 11 p.m. to 7 a.m., as the winter cold seeped into the city and into my bones, I found myself staring at Sara’s drawing, the one she hadn’t thrown away. All those rejected stamps, all those forms demanding proof of existence. I understood then why she had disappeared. The system hadn’t just failed her; it had erased her, piece by piece, form by form, until there was nothing left but the choice to vanish on her own terms. So I picked up where Sara left off and continued the forgeries.

It began with Petko. She was a quiet woman from Kurdistan with deep-set eyes that had learned not to expect much. Her asylum case was a tangled knot in its third year of appeals, and in the meantime, her temporary residence permit had expired. But she’d found something, a cleaning job in an office tower in Mitte; she had an interview for the morning shift.

« They need to see an ID to let me past the lobby security, » she told me at the reception desk, her voice barely a whisper. She pushed the expired card across the counter. The photo, taken on the day of her arrival, showed a woman ten years younger and a hundred years more hopeful. The expiration date, printed in the severe, no-nonsense font of German bureaucracy, was three weeks past.

I stared at the card for a full minute after she’d left for the communal kitchen. The machinery was already grinding her down. In my desk drawer, beneath a stack of intake forms, was Sara’s drawing of the rejected documents. I pulled it out. The stacked, angry red letters — Abgelehnt, Abgelehnt, REJECTED — were a monument to a person erased by paperwork. Rage, cold and sharp, coiled in my stomach. It was a rage I recognized from Sara.

In that same drawer lay the high-quality scan of Sara’s health insurance card she had once emailed me. My hand trembled as I took it out. It felt like handling a relic.

That night, after the last resident had gone to bed and the only sound was the hum of the ancient refrigerator in the break room, I began. The shelter’s office computer whirred to life, its screen casting a pale, clinical glow. Petko’s expired card lay on one side, Sara’s scanned card open in a graphics program on the other.

Sara had taught me the theory, but theory was a clean, abstract thing. Reality was this: the pixelated curve of a number ‘3’ under maximum zoom, the specific shade of institutional blue in the AOK insurance logo, the almost imperceptible watermark of an eagle hidden in the background. My first attempt was a joke. I printed a draft on standard office paper, and the result was flimsy and pathetic. The colors were washed out, the text looked fuzzy. I crumpled it, my fist tight.

The second attempt was better. I remembered a forgotten box of photo paper in the supply closet, thick and with a slight sheen. The colors were richer, the paper had weight. Now for the details. Petko’s name. Her birthdate. Simple text entry. The hard part was the date of validity. The original font was a variant of DIN 1451, a typeface designed for traffic signs authoritative, unrelenting. I found a free version online and downloaded it, my heart pounding with every click, half-expecting a silent alarm to trigger somewhere in a government building.

I typed in the new date, extending Petko’s legal existence by six months. The numbers looked too clean, too perfect. Sara’s voice was in my ear, a dry whisper from a smoke-filled memory: « They don’t look at the details, they look for the shape of compliance. Make it look a little bit wrong, a little bitsmudged. That’s how they know it’s real. »

With the mouse, I selected the date andnudged the text a fraction of a millimeter to theleft, making it slightly off-center. I applied a filterthat mimicked the bleed of ink from a low-resolution printer. It looked… plausible. I knew thechip was a dead piece of plastic, that any cardreader would instantly reject it. But this wasn’tfor a doctor. It was for a security guard in a lobby. This was a weapon for a visual battle, nothing more.

The final act was the lamination. The cheap office machine wheezed as it heated up, smelling of dust and melting plastic. I placed the printed paper, now trimmed to size with a shaking hand and an X-Acto knife, into a plastic sleeve and fed it into the machine’s groaning maw. It crept out the other side.

I held it in my palm. It wasn’t perfect. If you looked closely, you could see the flaws. But it had the weight and the unforgiving plastic sheen of an official document. It was a tangible, holdable lie. Getürkt was cementing itself in my vocabulary. I loved that it was a verb. It wasn’t just a state of being; it was an action, a word that meant agency and being proactive, albeit a slur.

The next morning, I saw Petko by the coffee machine. I didn’t say a word, just slid the card into her hand as I reached for a mug. Her fingers closed around it. She looked down, then up at me. Her eyes, for the first time since I’d met her, weren’t filled with fear or resignation. They were wide with a silent, shocked gratitude that was heavier than any accusation could ever be. She slipped it into her wallet and walked away, her shoulders a little straighter.

I went back to the office and looked at my own hands. They had learned a new language, the grammar of forgery. I had taken the system’s sterile tools and bent them. It wasn’t just paper and ink anymore. It was a key. It was a weapon.And my fingerprints were all over it.

I kept Sara’s drawing in my desk drawer, not her photo, but her final artwork of rejected documents. Each time I broke another law, I thought of what she had said: « Someone should remember. »

The operation grew careful, calculated. I only helped women within weeks of securing legal housing, only when the forgery was temporary, a bridge, not a permanent solution. But with each document, I felt myself crossing deeper into territory I couldn’t uncross. The hypervigilance was exhausting: checking security cameras, noting guard rotations, my pulse spiking every time someone knocked on the office door. I was breaking laws to help these women, bringing them closer to the inner logic of this shelter.

Sara’s health insurance card had a serial number that passed muster with German providers. She needed it to attend ten mandatory therapy sessions — a requirement before undergoing the next stage of her transition. That was the last bureaucratic trace I had. I followed up with the doctor more than once. Sara had never shown. I reached out to various public insurance therapy consultation centers, asking if Sara had come in. But all of them refused to speak, Schweigepflicht, confidentiality rules, even though I introduced myself as a social worker from the shelter where Sara had come for the last three months.

I kept giving myself the same pep talk: « No, this isn’t Istanbul, it’s Europe; things are rarely that bleak. » I would repeat it like a mantra to other residents and colleagues, unsolicited, in passing — as my guilt, my impotence in really helping, grew larger than any help I was actually providing. « Guilt is useless, just another form of privilege, » I told my reflection in another mirror talk. The very idea of saving someone is a trope born from privilege.

I looked again at the description of Sara I’d posted online, with all the « care » emojis and hearts fluttering around it like dying moths. Looking at the post once again, with its sterile description, felt like a betrayal. It reduced Sara — her rage, her laughter, her brutal honesty — to a set of measurements and colors. It was the very thing she fought against: a document trying, and failing, to capture a life. She would have hated it.

But then I held that image up to a prism in my mind. For a luminous moment, I saw her as a Greek statue, and it seemed to me that her life should have been mythic: a story defined by her own choices, not one where she was simply a passive recipient. If I’d said any of this to Sara, she would have laughed her ass off, then maneuvered to make a joke, saying, « And what about the king’s fool, my dear? »

The winter passed, long and unforgiving. Sara never reappeared, but her rebellion lived on in every signature I forged, every stamp I counterfeited. I was continuing her work, translating bureaucratic bullshit into something that actually helped people. Maybe she had always known this would happen. Maybe that’s why she had taught me.

When summer arrived, the homeless moved to the Spree canal. It gave them a view, tourist boats drifting by, moonlit nights, the convenience of water for washing and waste. I never found out what happened to Sara. Her file was eventually closed, her bed was filled by other women whose folder of papers was just as thick, just as complicated. I kept forging documents. Make it look real, Sara’s memory surfaced, a ghost of cigarette smoke. A little bit wrong. That’s how they know. It’s not perfect. It’s getürkt.

Payment came in books, novels, even self-published poetry, a bit of weed, some groceries. A few offered contacts for shady business ventures, temptations I tried hard to resist. I had promised myself: don’t get involved in crime. This life had to work.

But late at night, when the shelter was quiet and I sat at my desk with Sara’s drawing spread before me, I knew I had already chosen my side. Sara had been right about one thing: you had to pick a side in this city. I had chosen the side that said people should exist without having to prove it in ten different forms.

Somewhere, a photo of her still fluttered under a bus stop bench, unread, unremoved. I realized Sara might still be out there somewhere, living under a different name, with different papers, free from the endless cycle of documentation and rejection. Or maybe she had become what she always said she was, not real, at least not in the way this country demanded. But real enough to have taught me that sometimes the most radical act was simply refusing to participate in your own erasure.

You’re reading this essay for free. With a membership, you can read the full magazine, and you get access to our fabulous Library.

Here’s our offer: 3 months unlimited digital access + 1 print edition for € 38,00 € 19,00

You’ll get Issue Eleven in print as your first magazine, right to your mailbox.