translated by Ruth Ahmedzai Kemp

A group of « skinny Black lads » enroll at Leipzig’s Karl Marx University in East Germany. An excerpt from Jackie Thomae’s novel Brothers.

The following text is an excerpt from Jackie Thomae’s novel Brothers, translated by Ruth Ahmedzai Kemp and just published by Das Editions. The book originally appeared as Brüder in German in 2019, where it was shortlisted for the German Book Prize and awarded the 2020 Düsseldorf Literature Prize.

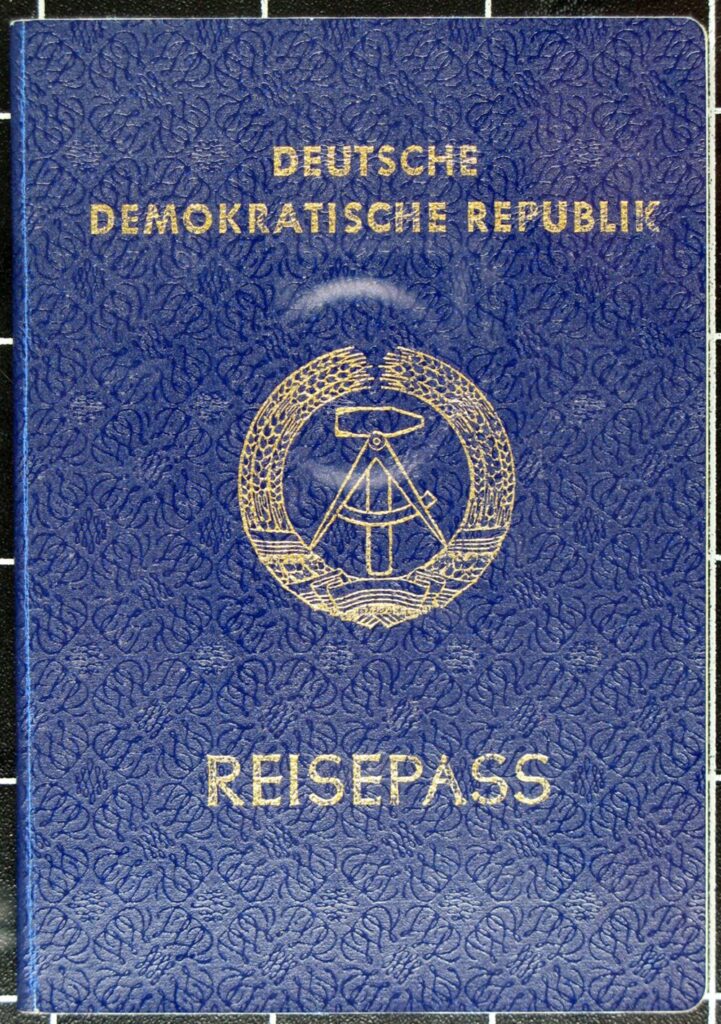

In the novel, two half-brothers, Mick and Gabriel, navigate through manhood determined not to let the colour of their skin define how they see themselves or impact the decisions they make. One a hedonist, the other an overachiever, they seem to have nothing in common but the year of their birth and a biological father – a Senegalese student in the GDR, who returned to Dakar leaving his sons with only his looks. As the jury of the German Book Prize noted about Brüder, Thomae manages « to weave existential questions and themes into it with great ease, almost in passing. »

The extract published below centers on the stepbrothers’ father Idris, when he’s briefly back in Europe. We find him on the train to Paris, overthinking a visit to Leipzig he just made with his friend Oumar. A trip to their old student halls brought back memories of the time when he, Oumar and other African students were first welcomed at Leipzig’s Karl Marx University, in the days of the German Democratic Republic.

Do you remember when we arrived here? Oumar asked him, as they stood in front of their old student halls. It had been rebuilt as a retirement home. Yes, he remembered. It was the first time he had been on a plane. He wasn’t the son of a minister or a diplomat like some of the others. His father had two grocery stores, and he was lucky to have been the only son whom his father went out of his way to send to the Lycée Français and then abroad to study. When he thought of that flight, he pictured little boys giggling with excitement.

They landed in Berlin-Schönefeld and were loaded onto buses and taken on to Leipzig. They came from different countries, different ethnicities at any rate. Not that anyone in Europe cared precisely where they were from. That had never mattered and never would. Many of them had state scholarships, others had applied privately for a university place, but for the Germans, they were simply a bunch of Black kids. For the authorities, they were African students from the young nation states. Newly independent nations that had thrown off the colonies. Military dictatorships, maybe, but the main thing was they were no longer under British, Portuguese, Belgian, or French control, and therefore had the potential to be won over to the socialist side. In Leipzig, they were taken straight to the university, Karl Marx University, KMU for short. It had only had that name since the fifties, but it had existed as a university since 1409. Idris remembered the date because he had been so impressed. They were shown around the faculty, shown their future lecture halls, the cafeteria, the sports facilities. They shook the hands of lots of important old men and were flooded by so many impressions at once that in retrospect it was a wonder that none of them fainted. Besides this, of course, their future professors, tutors, and supervisors were invariably German. That is, White. They all knew a few White people back home, but here everyone looked like that. He remembered pale faces in the cool neon light. They wouldn’t have been able to tell us apart either at first, Idris thought, and there was also the disadvantage that we were mostly male and about the same age, skinny Black lads around twenty.

On their shoulders, they were told, rested not only the hopes of the GDR, a nation that in its infinite generosity and solidarity had offered them their university places, on their shoulders also rested the hopes of their home countries, exploited by colonialism, imperialism, etc, etc. But all that was set to change. In part, thanks to them. Because they would go back home, straight after graduating. Oh, is that right? They would have nodded. None of them had been aware when they arrived that they were invited as future creators of a new, post-colonial Africa. They were struck by the idealism of these GDR officials, even if the delivery was somewhat lacking in charisma. Everyone was constantly reading from a script. These people knew nothing about Africa, but their euphoria about the future had something infectious about it, Idris found, at least to start with.

Not only did their hosts have no idea about Africa, neither did they know what their African guests thought about it all. For all that they were invested with the hope of future Pan-African socialism, these students’ focus was less long term, less complicated. Their thinking was straightforward: the important thing was Europe. It wasn’t for fun that their parents had sent them to the best schools. This was compounded by another misunderstanding: while the officials most likely expected a degree of humility from them, these delegates from impoverished countries, many of them in fact saw themselves as the crème de la crème, given their background and education. And yet, the idea didn’t occur to them that as well-educated men they bore some responsibility for progress in their countries. Though when you thought about it, it did make sense.

His mobile rang. He quickly pulled it out of the inside pocket of his sports jacket and turned the sound off. He still found it unbearable when people burdened others with their self-importance. It was the clinic, though he had impressed upon his staff that they should call him only in an emergency. He would call them back when he got there. He was looking forward to Paris and to seeing Amadou.

When, after graduation, they were all flung in different directions like a nuclear reaction, he was one of the few who went back, thereby fulfilling the official plan, if not his personal one. He was always reminded of that when he saw his old friends. Amadou, a slacker back then, had found himself a licence to print money with his orthopaedic clinic in Paris. Backs, knees, and the house speciality: hip replacements. A thriving granny repair shop in the French capital: you could hardly do better than that. Oumar was a consultant at a large hospital in Stuttgart. How ironic that he, the only one who had really complained of being homesick and who had nearly thrown in the towel, had ended up staying here, had become German, with a passport, a suburban house, a German wife, and two children. Very well, thank you, was Oumar’s reply to the question of how they were doing: Christine had moved onto a permanent contract in her public sector role. Well, good for them, thought Idris. He heard the muffled murmur of German being spoken in the train compartment and grinned to himself. The only thing about Oumar that wasn’t German was his looks. And he, Idris, who had never been homesick, who had always imagined himself staying in Europe, had gone back to Africa. Isn’t life absurd?

He put his phone away, sat back, and watched Germany pass by. Tidy, peaceful, green. It was a long time since he had been on a train and he had forgotten how relaxing it could be. When did he ever have time to think about the past?