Her new book, Unsilencing; The History and Legacy of the Bulgarian Gulag, is a study of Bulgaria’s forced-labour camps. She has traced the systematic repression of the communist regime by way of oral history, archival research, art projects, and an essay with us that later unfolded into a multimedia installation at the Venice Biennale. Topouzova, an assistant professor at the University of Toronto, is wrestling with a legacy that has been deliberately obscured. For the Gulag leaves a void in a nation’s collective memory — one that continues to reverberate in Bulgaria today.

SP

Hi Lilia. The book, what’s it about, and what are you up to?

LT

Hi Sander!!

Drinking coffee, looking out on Piazza Dante as I type this in Rome across the Italian CIA and getting to your question.

SP

Rome!

Why are you in Rome?

LT

To write

No affiliation, no accountability but to writing itself, sabbatical year away from everything.

SP

A sabbatical in Rome…

What are you writing?

LT

Sander, believe it or not, I am still writing about survivors of political violence because their words feel more urgent than ever in our current authoritarian-bent world. So I go on these long walks along the Colosseum, listening to my interviews with anarchists and others who defied Stalinist norms, people who believed it was worth resisting even when the odds were against them.

SP

You question your courage?

LT

Always. You can’t spend two decades working with fragmented testimonies of survivors, perpetrators and bystanders, while piecing together a history from purged secret police archives, and remain convinced of one’s hypothetical courage. This work constantly reminds me of how fragile courage is — and how it is our collective responsibility to uphold it.

I know firsthand too: I went from Communist to Catholic schoolgirl nearly overnight in the 1990s, and when geopolitical circumstances demand of you to trade allegiances, you realize that courage is fickle, contingent but ultimately something we hold in common.

SP

In 1990 the Communists gave up power in Bulgaria and schoolchild Lilia transferred to the Catholics. Did the pomp and circumstance of the church win you over?

with your Roman sabbatical

LT

Hahahaha. Not at all. What struck me wasn’t the pomp but the contrast. One year I was saluting Communist heroes, the next I was reciting Catholic prayers. I’d already stood before the embalmed body of Bulgaria’s communist dictator with lipstick-red lips — so the symbolic body of Christ felt like quite a shift, but also not. Rituals, whether red scarves or rosaries, carry enormous symbolic power, but they don’t guarantee belief.

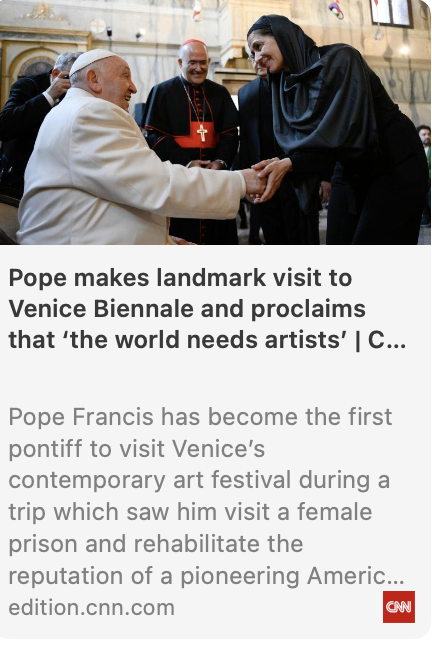

Also I suppose I’ve always lived within rituals of power, observing how they bind and unbind belief. Last year, I met Pope Francis at the Venice Biennale when he invited me and my colleagues, Julian Chehirian and Krasimira Butseva for a private audience because of our installation. Now he’s buried up the street from where I live, in Santa Maria Maggiore.

It’s a bit uncanny that my meeting with Pope Francis became the face of his first visit to Venice — that photo was everywhere, but I never wanted to be identified in it.

SP

Hé, I did not recognize you, I mistook you for a nun — I do not know if it is because of the veil or the look you give to the Pope.

LT

Following protocol sometimes turns you into a nun!

SP

Is it protocol that you cover your hair for the Pope?

LT

Yes

SP

There is a man on the pic without and on the other pic I see women with hair uncovered

LT

It’s for women only. Not everyone followed it.

« Protocol for papal audiences traditionally requires women to wear a black dress with sleeves and no cleavage, as well as a black mantilla or scarf for the head. Certain designated Catholic queens and princesses have nonetheless traditionally been exempted from wearing black garments. »

Since I am not a Catholic queen or princess…

To answer your first question, Sander. My book, Unsilencing, is the outcome of two decades of research and creative work, framed within the unlikely arc of a life that began with a Communist schoolchild bowing before the embalmed body of a dictator, and many years later, culminated in a meeting with Pope Francis at the Venice Biennale. It is a book about that arc — and about the role of unsilencing.

On one level, it reconstructs the history of the forced-labour camps and the policies of repression that enabled them. It considers the life stories of those who became guards, superintendents—people who carried out the violence. It follows the survivors, their children and others who inherited the silence of the gulag: what it means to grow up in its shadow, to navigate missing archives, erased testimonies, and tabooed family history.

It shows how silence became a political technology, extending beyond barbed wire into everyday life. By weaving together state archives with survivors’ testimonies, I wanted to show that history and memory are inseparable — and that unsilencing is itself a method.

SP

Why did a schoolgirl go to see his embalmed body?

LT

We had to go and see his body to pay homage. It was an obligatory school trip for all of us.

Students in the Lenin youth.

There!

Not a visit you can opt out of.

SP

What is left of the Gulag history that you haven’t told and now need to write about?

LT

🙂 That’s the question I usually ask my respondents at the end of an interview. So what is left? The off-the-record answers and unfinished stories.