Even asleep, we remain citizens

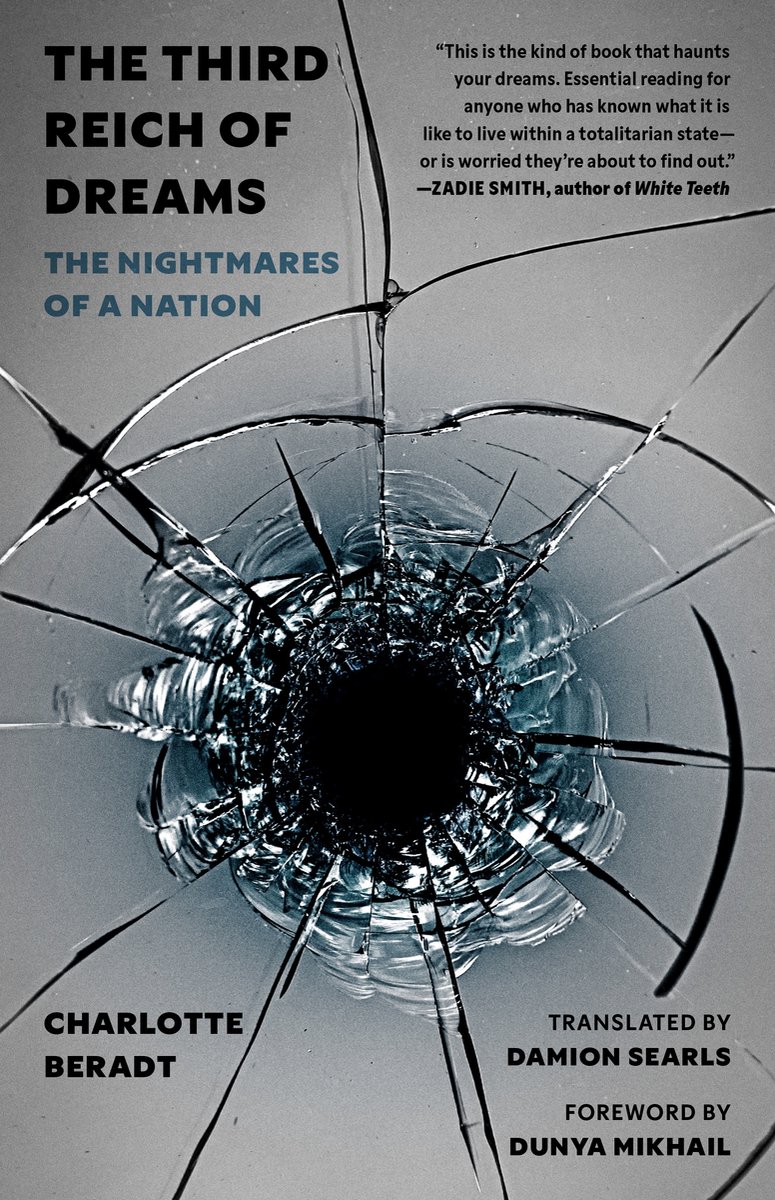

The Third Reich of Dreams: The Nightmares of a Nation

Charlotte Beradt

Translated by Damion Searls

(Princeton University Press, 2025)

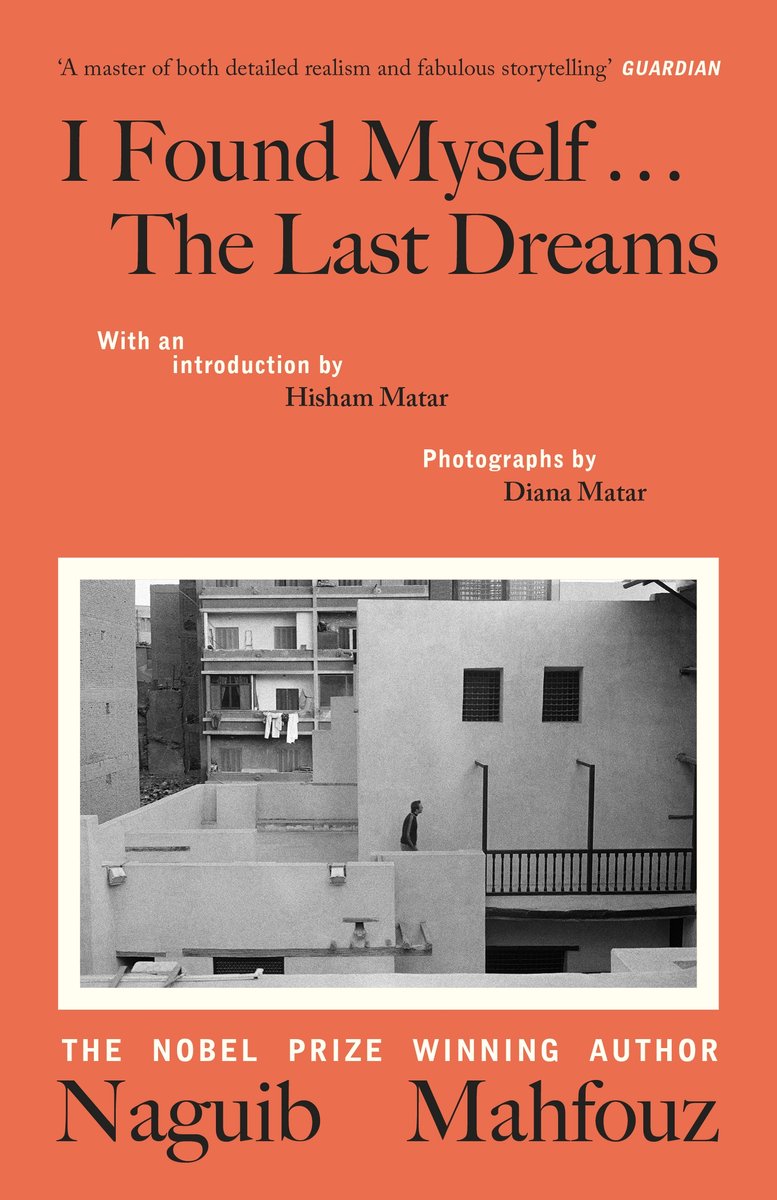

I Found Myself… The Last Dreams

Naguib Mahfouz

translated by Hisham Matar,

with photographs by Diana Matar

(New Directions, 2025)

An animating paradox of psychoanalysis is that while dreams are (or can be, or should be?) the most uninhibited realm, the telling of dreams involves curiously stable forms that take few liberties. As C.G. Jung observed in « On the Nature of Dreams » (1945), dream narratives typically follow a rigid dramatic structure: 1) the exposition, which involves a statement of place and identification of the protagonists, 2) the development of the plot, 3) the culmination of the plot, and 4) the solution or result. As children, one of our earliest exercises in narrative-making, in fact, is our shaping (or constraining?) of the anarchy of a dream — or the cognitive bedlam of a nightmare — into the communicable frame of a story.

Narrating a dream is, as the scholar of dreams Sharon Sliwinski has written, « an undoubtedly strange kind of speech, one we are not exactly the authors of. There is a fundamental distinction between the dream-as-dreamt and the dream-as-text, that is, from the actual experience of dreaming and the presentation of this experience in language afterward. » No wonder writers and artists have found the telling of dreams a fruitful challenge, and no wonder we might want to read their dream journals. The Swedish theologian and mystic Emanuel Swedenborg, the Italian filmmaker Federico Fellini, the French ethnographer Michel Leiris, the American musician Henry Rollins, and the writers Franz Kafka, William S. Burroughs, Graham Greene, Georges Perec, Vladimir Nabokov, and Jack Kerouac — all of them recorded their dreams. The Frankfurt School philosopher Theodor Adorno kept a particularly racy journal of his nocturnal phantasmagoria: visits to brothels, a parade of famous faces (Jean Cocteau, Peter Suhrkamp, Leon Trotsky, Kaiser Wilhelm, Gershom Scholem, Fritz Lang), beheadings and torture and concentration camps and crucifixion, a couple of dinosaurs. In 1967, Adorno dreamt that his mistress wouldn’t give him head (« mit dem Mund lieben ») until he bought a « Schwanz-Waschmaschine » (a prick-washing machine). The story of that one ended with a return to real life: « Woke up laughing. »1 As wild as the content of Adorno’s dreams was, they always had a beginning, middle, and end.

Do dreams have a politics? Sliwinski’s Dreaming in Dark Times: Six Exercises in Political Thought (2017) offered several answers to this question. Each chapter is dedicated to specific time-space coordinates that intensified the political dimensions of dreamlife: « a notorious prison from apartheid-era South Africa », « the tangle of sexual relations in fin de siècle Vienna », « an Allied military hospital during the Great War », « one of the longest city sieges in history, the London Blitz », « the psychiatric wards of colonial Algeria », and « Berlin under the Third Reich ». In Sliwinski’s interpretation, dreams and their tellings — or at least some dreams — can be sources of political empowerment: « speaking of one’s oneiric life can serve as a particularly potent strategy for negotiating and resisting certain forms of sovereign power — a means to unsettle the power-knowledge relations of a given era ».

Then again, dreams could show an internalization of oppression just as easily as a resistance to oppression — which would mean a dream isn’t so free a realm after all. Dreams can dramatize not empowerment but powerlessness — in the face of strongmen or unruly mobs, for instance. In Rome in October 1966, Adorno dreamt of « countless people assembled, a mixture of riff-raff and monstrosities, figures with bald heads and tentacles » who « stared menacingly » and « were suspended, like bunches of grapes, immediately under our window, ready to fall upon us. » His journal spliced in an explanatory parenthesis: « (The motif here may be the formation of a Chinese wing among the Italian communists.) »

Or dreams tell the future. The practice of foretelling developments on the horizon, political or otherwise, is called oneiromancy. Ancient leaders in Mesopotamia, Assyria, Egypt, Greece, and Rome built temples, changed military plans, or altered their political programs in the wake of vivid dreams. Abraham Lincoln dreamed of his own assassination — or so recalled his friend and bodyguard Ward Hill Lamon in a book from 1895, in a chapter called « Dreams and Presentiments ». Lincoln told that in a dream, he’d wandered into the White House’s East Room and saw a « sickening surprise »:

Before me was a catafalque, on which rested a corpse wrapped in funeral vestments. Around it were stationed soldiers who were acting as guards; and there was a throng of people, some gazing mournfully upon the corpse, whose face was covered, others weeping pitifully. « Who is dead in the White House? » I demanded of one of the soldiers. « The President, » was his answer; « he was killed by an assassin! »3

Several of Adorno’s dreams in the early forties anticipated Hitler’s fall and the harsh retribution faced by the surviving Nazis. In all these cases, matters of great urgency to the polis are first rehearsed in the night-time brains of individuals. Even in sleep, the human is a political animal.

You’re reading this essay for free. With a membership, you can read the full magazine, and you get access to our fabulous Library.

Become a member and get Issue Ten in print as your first magazine, right to your postbox.

Charlotte Beradt, a German-Jewish journalist born in 1902, watched in horror as the Nazis marched through the streets of Berlin in 1933. She noticed her own dreams changing as Hitler gained power; conversations with friends and acquaintances revealed the phenomenon was widespread: « the Third Reich sentenced a very large number of people indeed to similar dreams », she would later recall, and decided « that dreams like this should be preserved for posterity. » Between 1933 and 1939, she deftly catalogued the Nazis’ burrowing into the folds of the subconscious in her inventory of nightmares and unsettling dreams dreamt by Germans — more than three hundred of them. Her own dreams are left out of the volume, or at least never explicitly attributed to her.

Beradt kept her catalog secret, slipping the dream scraps into the bindings of her books and eventually smuggling them out of Berlin in 1939, when she emigrated to the United States. Her volume Das Dritte Reich des Traums (The Third Reich of Dreams) didn’t appear until 1966, when she was living in New York, working closely with Hannah Arendt and translating her works from English to German. (Before leaving Germany, she had also translated Charlie Chaplin’s My Trip Abroad [1922] as Hallo Europa! [1928] with her husband Heinz Pol). Beradt’s dream book has since become a classic not only in Germany but across the world, translated into many languages. Damion Searls’s new English translation, published by Princeton University Press, is the latest in a long line of attempts to convey the linguistic richness and surprise of the original.

What is such a catalog for? First, it sought to disprove the commonplace — uttered by the Nazi head of the German Labor Front, Robert Ley, and Beradt’s ironic epigraph for the book — that « the only private individuals left in Germany are people sleeping ». Beradt revealed the contrary fact that the Nazis had infiltrated dreams, colonizing even the resting mind and thus making public that one last private space, the inside of one’s skull.

While gathering the dreams in the 1930s, she imagined an additional forensic or juridical purpose they might someday serve:

They might serve as evidence, if the Nazi regime as a historical phenomenon should ever be brought to trial, for they seemed full of information about people’s emotions, feelings, and motives while they were being turned into cogs of the totalitarian machine.

The inventory she had gathered, it was important to note, revealed more than an intentional dream journal could: after all, the very act of keeping a journal « shapes, clarifies, and obscures the material in the process. » Beradt had gathered not a diary — Tagebuch, literally day book — but a Nachtbuch, which Searls masterfully renders as nightary: « not diaries but nightaries, you might say ». Those dreams, she went on, « emerge from involuntary psychic activity, even as they trace the internal effects of external political events as minutely as a seismograph. » No longer evidence for some future trial, those dreams now stood as seismographic data from an earlier earthquake: invisible psychic tremors recorded in a time of widespread terror.

Beradt suggested, in effect, that the future severity of Nazi terror had been detected by the dreams of German citizens long before the war began. Here, in other words, was a tool of psycho-political measurement more precise than a traditional or folkloric oneiromancy. « Thus dream images, » she argued, « might help interpret the structure of a reality about to turn into a nightmare. »

The book has had a remarkable afterlife. The first English translation, by Adriane Gottwald in 1968, included an essay by Bruno Bettelheim (1903-1990), the Austrian psychologist who himself had emigrated to the U.S. in 1939, after a short imprisonment in both the Dachau and Buchenwald camps. « It is a shocking experience, » Bettelheim affirmed, « reading this volume of dreams, to see how effectively the Third Reich murdered sleep by destroying the ability to restore our emotional strength through dreams. » In his day, he was most known for his work on children’s mental health; in Beradt’s book he saw evidence that the Nazis had essentially reduced German dreamers to their childhood selves:

[W]e must compare these dreams with ones that occur normally when a person is subject to a superior power in his life. Such dreams are typically true of the small child, because his life is so largely controlled by and dependent on others: his parents, his teachers, adult society, and their demands.

Bettelheim’s early reflections on dreams in the context of Nazi Germany almost certainly contain within them the seeds of a later project: The Uses of Enchantment (1976), his book of Freudian interpretations of fairy tales. In dreams and fairy tales alike, something lurks in the shadows at the edge of the woods.

Of the many Blut-colored threads that run through Beradt’s catalog, one is that totalitarianism can only work when people acquiesce, even if it’s just a few at first. This is the thesis foregrounded by the Germanist Barbara Hahn, in her afterword to a Suhrkamp edition that appeared in 2016:

Ohne Mitläufer können totalitäre Regimes nicht überleben. Beradts Buch zeigt, wie Menschen zu Mitläufern werden. Wie sie sich zurechtbiegen, ihren inneren Widerstand brechen. Das Dritte Reich des Traums — auch eine Theorie totaler Herrschaft.

[Without followers, totalitarian regimes can’t survive. Beradt’s book shows how men become followers, how they bend themselves, and break their inner resistance. The Third Reich of Dreams is also a theory of total power.]

I’ve rendered Mitläufer here as « follower », but it could also be translated as tacit supporter, non-resister, hanger-on, someone who wades passively into a black pond until it swallows him whole. I can’t help but notice that the edition came out in 2016, a fateful year in which Mitläufer in the United States, coaxed into it with the help of neo-fascists and billionaire ghouls, let a grisly, now seemingly irreversible thing happen.

The new English edition is introduced by the Iraqi-American poet Dunya Mikhail, who compares the « oppressive atmosphere » that reigned during her studies at the University of Baghdad, to the one Beradt describes in her catalogue of nightmares. The foreword draws parallels between Beradt’s dream collection and her own experience of life in Iraq under the rule of the Ba’ath party, both of which resembled Orwell’s 1984:

The « thought police » turned citizens against each other through fear. Children were encouraged to report on their parents, and writers were incentivized to spy on one another, creating a society where trust was virtually nonexistent.

How unique should we consider the dreamscapes of the Nazi regime to be? Beradt claimed that the dreams she collected were specific to it: « they could only have emerged from the paradoxes of life under totalitarianism in the twentieth century, and most of them specifically from Nazi Germany ». Many readers who did not live in that context, perhaps contemporary readers in particular, might dispute her confident assertion. Zadie Smith states as much in her cover blurb, calling the book « essential reading for anyone who has known what it is like to live within a totalitarian state — or is worried they are about to find out. »

The Third Reich of Dreams is timely for all the reasons you would expect. If your compatriots are flirting with or are already in a committed relationship with an authoritarian, your dreams may have begun to resemble those of Beradt’s dark catalog.

Do you dream « bureaucratic atrocity stories », like the one I had a few weeks ago? A Latin American strongman with an uncanny resemblance to a certain contemporary Salvadoran leader was responsible for making new traffic laws in the United States, but they all contradicted one another, so by following the law, you were nonetheless breaking it, risking imprisonment or torture. I don’t recall ever having had a dream in the past with such concerns at its core, which leads me to think it is a product not of my unconscious but of our moment. A dreamer of Beradt’s gets a call in the night, with the anonymous speaker saying one haunting line — « This is the Telephone Surveillance Office » — and then hanging up. In Beradt’s account, this phrase left the dreamer « in the Kafkaesque state of being accused without knowing the accusation ». Nazi-era dreams were full of bureaucratic offices, expressionless civil servants, and omnipresent propaganda in the form of « loudspeakers, banners, posters, headlines, the whole arsenal of media in the regime’s news monopoly », all reinforcing the fact that the new bureaucratic imperatives must be obeyed.

Have you begun to dream of people who sided with you and your political protestations in the past but who now have become « men and women who merely stare into space ‘mute and expressionless,’ » and with « impassive faces »? Do you dream about accidental infractions against the powers that be? Are you passive? Does the everyday take on absurd qualities, like when one man dreams, « I was telling a forbidden joke, but I was telling it wrong on purpose so it made no sense »?

Do you dream that your difference makes you a target? One can’t help but empathize with the dreamers in Beradt’s chapter on « The Dark-Haired in the Reich of the Blond », whose difference glares in the light of day. Women navigate the dream world terrified that they possess « non-government-approved hair » or a « government-rejected nose ». One dreamer is relieved to find a comforting refuge:

Suddenly I was lying at the bottom of a big pile of dead bodies, I didn’t know how they got there, but at last I’d found a good hiding place. Pure bliss, a sense of salvation, under the pile of corpses with my folder of papers under my arm.

Or do you dream of siding with evil to protect yourself from it? Beradt’s tenth chapter collects dreams of those who make deals with the devil:

What we’ve seen as a secondary motif in earlier dreams — being an advisor or friend to Hitler, Goering, or Goebbels — is here the main topic. The dreamer childishly exaggerates his or her personality or status, rather than satirically distorting it: « I’m Hitler’s right-hand man and I’m happy about it. » Dreams like this, which can be summed up in a simple, one-sentence wish, are typical of children, who have not yet learned how complicated adult wishes can be.

Finally, do you dream that inanimate things have become surveillance tools? A particularly distressing theme running through Beradt’s book is that of the listening object. Various everyday objects eavesdrop on their dreaming owners — a tiled stove, dental equipment, a bedside lamp, « mirror, desk, desk clock, Easter egg », decorative angels hanging above the bed. In one horrifying scene, a man is denounced by his own pillow. In our day, the domestic space is populated voluntarily with listening, seeing, sensing objects — Siri and Alexa, Ring cameras, smart appliances, the Internet of (Awful) Things — with little thought given to their nefarious affordances. A corporation or a government will certainly know how to put them to good use.

The Third Reich became, understandably, the default political nightmare — the thing against which the political nightmares of later eras would be measured, a signifier or symbol, a motif in its own right that could cameo in later eras’ dreams. Almost half a century after World War II, Hitler’s favorite field marshal, the Desert Fox, invaded the dreams of the Egyptian writer and Nobel Prize winner Naguib Mahfouz:

I found myself holding Aladdin’s lamp. I asked the genie to bring my beloved A. back from the dead. And just then I was back to being a minor employee, a writer who failed to have his work published anywhere, watching a demonstration and listening to the frightening chant: « Rommel, advance. » I saw Nazi and fascist banners waving in the air, and a dark despair spread across millions of people. My beloved rushed to the lamp and begged the genie to return things to how they were before.

Mahfouz’s conjugation of a personal tragedy — the death of his lover — and the collective tragedy of Nazi rule shows the extent to which the nocturnal subconscious allows no separation of self from the polity. Mahfouz would have been around 28 years old at the beginning of the war, but its horrors followed him into old age, seeping into this dream, which he likely dreamt in his eighties.

Mahfouz (1911-2006) began to record dreams like this one, inventoried in I Found Myself… The Last Dreams, a new English translation of which has just appeared from New Directions. It is a compendium with concise numbered entries that sketch the dreams he had after he was stabbed twice in the neck by a stranger in Cairo in 1994, which, the attacker said, was retribution for the depictions of God in Mahfouz’s novels.4 It was a style of attack suffered in 2022 by Salman Rushdie and addressed in his recent book Knife: Meditations after an Attempted Murder (2024). Before I Found Myself, Mahfouz had already published dream books, including the 1982 short story collection Ra’aytu fima yara al-na’im (« I saw as the sleeper sees ») and, between 2000 and 2003, a first volume of post-attack dream writing, Ahlam fatrat al-naqaha (« Dreams during a period of convalescence »), an English version of which appeared in 2004, translated by Raymond Stock. I Found Myself… The Last Dreams is the posthumous culmination.

In addition to his waking talents, Mahfouz possessed a vivid nocturnal imagination capable of conjuring up just about anything. The dreams circle around erotic longing, familial discord, friendship, loss through death or amorous separation, and the future of Egypt (in two grandiose dreams, he imagines himself on the national soccer team, a hero to his compatriots). The settings are bedrooms and courtrooms, police stations and parks, cafés and balconies. Like all dreamlife, Mahfouz’s toggles between the general (a woman, a city corner) and the specific (the Bein Al Janayen district, « my late friend, the barrister A »).

The translator, the Libyan writer Hisham Matar, hints at the dreams’ political resonances:

In the light of the present post-Tahrir Square Egypt, several of these dreams — dreamt about seven or eight years before the Arab Spring — are oddly prophetic in how they depict national unrest and unfulfilled democratic yearnings.

Distant in time and space from Charlotte Beradt, Mahfouz’s terrifying ordeal nonetheless produced a similar occasion: dreams themselves were transformed by terrifying ordeals and distressing events, spurring a new inventory of nocturnal imaginings. Both books leave readers contemplating the ways waking life and its often gruesome blows trespass on the subconscious.

Strong men, for instance, make regular appearances in Mahfouz’s dreamscapes. He admires many of them, including President Gamal Abdel Nasser. But regardless of whether they appear in positive guises (in Mahfouz’s dreams) or in negative ones (in Beradt’s collection), they summon to mind Jung’s Ruler archetype, or the Emperor card of the tarot’s Major Arcana in their stern, enthroned, masculine authority. The impassive leader has a special table always reserved for us in our dreams.

You’re reading this essay for free. With a membership, you can read the full magazine, and you get access to our fabulous Library.

Become a member and get Issue Ten in print as your first magazine, right to your postbox.

Mahfouz’s dreams tend to conjugate sentimental and political life. In them, he communes with friends, family, and lovers dead or alive in front of a backdrop of large-scale social unrest. After the stabbing, his physical health and psyche were never the same, and even in sleep he felt unsafe. Danger lurks throughout Mahfouz’s dream catalog in the form of pickpockets, thieves, dog killers, strongmen, soldiers, and angry mobs. He seems to have been especially marked by the power of crowds. Three different dreams in his catalog have him surrounded by masses of people, always with an ambient dread:

Dream 217

I found myself in a large demonstration that filled the squares and streets. Those in the front lines carried large photographs of Ahmed Urabi, Saad Zaghloul, and Mustafa al-Nahas.5 Their chants rang loudly, calling for a new constitution that was fit for the times. Unable to disperse the demonstrators, the security forces still appeared resolute.

Dream 239

I found myself in a dense crowd. It was the day of global elections: all the nations participated and I saw kings, presidents, and the elite disguised as peasant girls. They sang the most noble and beautiful songs. I cast my vote and wondered: What will the results be tomorrow, what will their impact be on the country and on the nations of the world? All the polls predicted catastrophe.

Dream 286

I saw myself taking part in a silent demonstration that had filled the streets and squares. I noticed among the faces people who, at one point or another, had departed from this world. They broke the silence and turned the demonstration into a loud and hostile one. The atmosphere became tensed (sic) and charged with danger.

It is the political dimensions of the inventory that haunted me the most, reminding me of how uneasy I feel at political marches even when I agree with the demands being screamed. Mahfouz dreamed regularly of implacable crowds, sometimes made up of both the living and the dead, thronging the streets.

This edition of I Found Myself pairs Mahfouz’s dreams with photographs — black and white, eerie — by Diana Matar. If Mahfouz is the written inventory’s protagonist, the protagonist of this oneiric photography is Cairo itself. Diana and Hisham are wife and husband; introducing the photographs, Hisham writes that « very much like an unforgettable dream, the images she captured are vivid, haunting, oddly mobile, uncertain. » Not unlike Beradt’s catalog, these photographs were secreted for a time, only to emerge later:

She kept them in a drawer for a long time. And as history moved on and it became, for political reasons, nearly impossible to photograph freely in the streets in Cairo, the images, like Mahfouz’s dreams, began to seem the previsions of the diminished present.

The photographs show people, sometimes crisp, sometimes blurred with motion, suspended in nostalgic graininess. They glide through Cairo’s pale-walled streets, engaged in their assigned duties as merchants, police, shepherds, businessmen, or wives. There are also contextless objects like bread, fish, trees, birds, dead chickens, and railroad tracks, lodged in an eternal present.

In contrast to the rigid narration of dreams, the oneiric photograph offers atmosphere, suggestive juxtapositions, and an occasion for the viewer’s free associations to unfurl. These images recall Eugène Atget’s fin-de-siècle Parisian dreamscapes, with their streets emptied of people, leaving trouvailles or found objects in a desolate city. Or Walker Evans’s at once documentary and dreamy record of Depression-era tenant farmers in Let Us Now Praise Famous Men (1941), with its spare homes of the working poor. Or Maya Deren’s experimental filmic dreamscape Meshes of the Afternoon (1943), with its contextless scenes of a woman interacting with objects, moving through spaces where the laws of physics and reason are loosened. My favorite among Matar’s photos shows the backs of three men in a line walking toward another man coming from the other direction. Shadows thrown across the wall behind them form an elongated grid that transforms the street scene into something resembling a German Expressionist film. Their configuration lasts for a split second; then they slide back down into the shadows of anonymity.

One of the most essential freedoms — for Mahfouz, for Beradt, for all of us — is the freedom to dream. It is worth a glance back at that most influential of dream inventories: The Interpretation of Dreams (1899), created when publishing such a thing (with scientific ambition, no less) was still a rather peculiar thing to do — so peculiar that it required a preface acknowledging the difficulties of gathering and conveying the material itself. Freud had at his disposal only « my own dreams and those of my patients who were under psychoanalytic treatment. » Patients’ dreams were dicey, though neurotically revealing. To publish his own dreams was dicey in another way. It would require him « to expose more of the intimacies of my psychic life than I should like » — no easy task for « an author who is not a poet but an investigator of nature. »6

The Interpretation of Dreams is now more often cited than read; it is refreshing to read its delicate, first-person championing of the freedom of thought that every dreamer deserves. Freud’s own dreams do appear in it. « This was painful, but unavoidable. I had to put up with the inevitable in order not to be obliged to forego altogether the demonstration of the truth of my psychological results. » And he had to « resist the temptation of disguising some of my indiscretions through omissions and substitutions », because « as often as this happened it detracted materially from the value of the examples which I employed. » Hence his humble request, before throwing the reader in:

I can only express the hope that the reader of this work, putting himself in my difficult position, will show forbearance, and also that all persons who are inclined to take offence at any of the dreams reported will concede freedom of thought at least to the dream life.

This defense of the liberated dreamer, whose loosened tongue might freely unfurl to externalize what the mind had kept to itself, is predictably urgent again. Instead of the involuted subject whose thought and speech collapse inward under the pressure of overbearing men, a person of freer mouth and mind had better say what she has to say while she still can.

- Theodor W. Adorno, Dream Notes, translated by Rodney Livingstone (Polity Press, 2007). ↩︎

- Theodor W. Adorno, Dream Notes, translated by Rodney Livingstone (Polity Press, 2007). ↩︎

- Ward Hill Lamon, Recollections of Abraham Lincoln, 1847-1865 (A.C. McClurg & Co., 1895). ↩︎

- Soon after Mahfouz’s death, his American translator Raymond Stock recounted the brutal attack against Mahfouz: « On Friday, October 14, 1994, an Islamist militant, allegedly acting on orders from blind Egyptian cleric Omar Abdel-Rahman, stabbed Naguib Mahfouz twice in the neck with a switchblade as he sat in a car outside his Nileside home in Greater Cairo. » Raymond Stock, « Naguib Mahfouz Dreams — and Departs, » Southwest Review 92, no. 2 (2007). ↩︎

- Ahmed Urabi (1841-1911) was an Egyptian military officer, Saad Zaghloul (1859-1927) was the Egyptian stateman and revolutionary about whom Mahfouz had several recurring dreams, and Mustafa al-Nahas (1879-1965) was Prime Minister of Egypt. ↩︎

- The Interpretation of Dreams, third edition, translated by A.A. Brill (Macmillan, 1913). ↩︎