My neurologist calls it a disease.

Science calls it a wrong signal.

The Vatican calls it human dignity.

Incontro con il Collegio Cardinalizio

Pope Leo IV

2025

Antiqua et Nova: Note on the Relationship Between Artificial Intelligence and Human Intelligence

Pope Francis

2025

0

A knitting needle pierced the upper molars on the right side of my jaw and stabbed backwards into my eye. The needle became a branching pain that gripped toward my ear as well. My legs played up, driven by an urge to contract, release, and tense again. I sat up, but movement made it worse. The pain sat at the front of my head, on the right. My right nostril was streaming, my right eye squinted, watery it became. I opened it, but even the faint glow from the curtained window was too bright.

It was about three a.m. and it happened just after my twentieth birthday. I was spending a month in a beautiful, bright apartment in the center of Amsterdam, on one of the stately streets beside the Van Gogh Museum and the Concertgebouw. Modern art on the walls, everything white. The bedroom was at the back, with a high ceiling and curtains that brushed the floor. On the large bed lay a white, thick yet featherlight duvet. A woolen rug covered most of the wooden floor.

What was happening? My blood thudded in a vein beneath my right cheekbone. Then another sharp stab. Was something ripping inside of me? The pounding went on.

I got up and stumbled, half by touch, half peering through the slit of my left eye, to the bathroom. Without turning on the light, I groped for an ibuprofen and two paracetamol. I swallowed them, drinking straight from the tap. Tilting my head I pressed the right side of my skull beneath the jet. The cold and the pain merged, but pressure grew underneath. God, this pain.

My head still wet, I went back to bed. I sat folded up, arms around my legs, forehead against my knees, rocking a little now. Was it toothache? I touched my molars, tapped them. Each on its own didn’t hurt.

Lights flared into bright rings projected on the inside of my eyelids, rebounding there and sent to the iris itself. Strange visions followed: my face — scrack — shattering against the marble tabletop before me, my nose and cheekbones splintering, my teeth breaking on the smooth, unyielding surface. My mouth filled with shards. The stumps would grind if I bit down gently, their glassy edges scraping together. The roots had become three-headed rivets, hammered deeper into the jaw, into the sinus cavity.

All of it on the right side of my head.

My mind sought images to grasp the pain. It didn’t understand what was happening, where it came from.

My fingers, I thought of my fingers caught in a car door: that instant before the pain begins, when everything is numb from the blow; knowing it’s coming — then the thin, sharp sting, and finally the blood pumping the worst of it through the nerves: dull, heavy pulses at their core.

Sensations kept coming. Nails screeching across a blackboard — no, across car paint — a sound that enters not only through the ears but through the fingertips, through the eyes, into the brain.

I tapped my head softly against my knees. I wanted to smash it against the wall — my forehead against the white-painted bricks, scraping until the chalky paint wore through and the skin caught on the tiny pits of the stone, leaving a blood-red patch against the white.

What was happening?

I wanted to rise from the bed, to hurl myself through the window — through the curtains, out into the air. The glass would shatter and scatter across the street. I saw fire. The dresser was burning; tall flames were climbing the wall. I wanted to step into the fire, to break the wooden cabinet apart, to destroy it. Violence.

And then, suddenly, it was gone — as abruptly as it had arrived. The world turned white again. Warmth flooded me. The room was beautiful. My head floated above the clouds of the duvet. High. Stoned. Blissful, I fell asleep.

At around six it happened once more. Again I staggered to the painkillers. Again they failed. Again the craving came — destruction, ruin, the urge to attack the bedroom wall.

The rest of the day I drifted in a fog. I did not get dressed. I stayed inside that vast, silent house.

Evening folded back over me.

And now, for the truly absurd: the next night it happened again, at the same hours. Twice, about an hour each time. In the final stage it was so bad that, in the flames before my eyes, I saw images of the Holocaust, of a South African boy with a petrol-soaked tyre around his neck. It is shameful.

In the days and weeks that followed, it struck almost every night — sometimes once, sometimes four times. I went to a GP, a dentist, an ENT specialist. No one found a thing.

My conclusion: I was going berserk. You can’t have pain every night, at the same hours, for fifty minutes, without something being really wrong. And those visions, that urge to crash into the wall or through the window — this had to be madness. I was hallucinating.

It took months before I found the neurologist I still see, about thirty years later. He diagnosed chronic cluster headaches: attacks of an intense, one-sided pain that lasts about an hour and is barely manageable. At the time, I had two to six attacks in 24 hours. I began taking high doses of medication, combined with injections when an attack came on. What was wrong? The neurologist shrugged and said some of what happened could be tracked, but that a cause had yet to be determined. He warned me that now began a life in which I’d be told that I was too stressed, that I should slow down, should be more active, must not eat this, not drink that, start meditating, try acupuncture, swallow salt, take ice baths, drink my piss.

You’re reading this essay for free. With a membership, you can read the full magazine, and you get access to our fabulous Library.

Here’s our offer: 3 months unlimited digital access + 1 print edition for € 38,00 € 19,00

You’ll get Issue Eleven in print as your first magazine, right to your mailbox.

I

Years later I found myself on a writing spree.1

Don’t be afraid, dying does not exist.

Zoom in on your final moment and stretch it out.

Come on now — unfold it. Together we’ll pry open time.

I’ll prove to you that people don’t die.

A whole body stopping at once? Look — the hair grows into the coffin’s crevices, the nails go on adding and adding, turning into avian claws.

Molecules float, strings vibrate, waves wallow,

particles perpetrate their spooky action at a distance,

DNA lives on, bacteria run amok.

Rot, wither, decompose, digest, germinate — you will scatter.

Brain functions don’t stop all together, exactly, in one magical moment of time. They fall away, one by one, as the last drops of blood deliver the last oxygen to each part of your brain. Your biological clock is not the very last thing to stop. Your sense of time disperses during these final moments: thoughts, dreams, intuitions, impulses rage without beginning or end. And in that simmering — you’ll live forever. Easy.

I wasn’t even writing about how you’ll live on in cloud storage, in memories, in photographs — and, for the raring writers: in books. I sat behind my desk, pulled back from the keyboard, reached for my glass. My lower back throbbed. A ball under my skin, a rugby ball, an orb of pain. A small device was implanted there: a battery pack with a chip and transistors. The neurostimulator sat beneath my skin, against the muscles of my lower back — solid, rectangular, a lump above my bottom. My body had built a membrane around it, encapsulating the metal. But now something was off. The artefact was playing up, my body was trying to toss it out. I reached around, cupped the metal box in my flesh, tugged a little. It slid beneath my skin. I imagined it felt hot.

It wasn’t supposed to hurt there. The battery and chip sent electric pulses all the way up to my brain to combat the headaches. With my fingertips, I traced the wire that climbed along my spine rolling it from side to side. The wire felt oddly old-fashioned. Halfway up, two narrow extension blocks were tangible behind scars — like the little plastic junction boxes used to extend household cables. In the nape of my neck, a block sent four electrodes left and right, transferring current along the nerve pathways. I had a remote control — yes, a remote control — to adjust the voltage. Some weeks I ran 2,2 volts through my head day and night. 5,8 volts was the highest dose deemed safe, but I had never gone past 4,8; the feeling became too distressing. From 1,8 volts onward I felt what I called a « presence » in the middle of my head. Turning it up brought a spreading discomfort, a prickling of the scalp. Leiden University Medical Center had asked me to experiment with the voltage. It was designed to stimulate the nervus trigeminus, deep in the head, near the temples, splitting into three branches — to the forehead and eyes, to the cheeks and upper teeth, and to the lower jaw and tongue. The hope was that stimulation, during or between headaches, would make the nerve less likely to play up.

But something was wrong. The tissue around the device swelled. Fever came. Focus came. I typed like a man possessed. Here I was, after midnight still at my desk — a washstand really, with a heavy marble slab, cool to the touch. My left forearm rested on it, the back of my hand against the stone.

See your fingers curl of their own accord into a half-claw.

Now fold in your thumb.

Can you still feel the soft pads beneath your fingers, on your palm?

Squeeze.

When will your body stop belonging to you?

I was writing a MANIFESTO. I’d convinced myself that I had to show what it means to be human — that humanity is a deep mystery, accessible only through faint understanding, through sense, through feeling. The fever from the inflammation must have been at play.

The heart stops. But what does stopping mean?

The contractions of the heart subside.

Doctors see no more measurable activity on their EEGs and MRIs.

Are we but the brain-activity that scientists can detect?

Is our personality equal to measurable activity?

I pushed two painkillers from a strip and swallowed them with a gulp of wine. Come on now. I’d found out why we don’t die. First: I could be anywhere. I was even reported to be present in my shit — there’s a worldwide industry devoted to the impact of gut microbiota. Well then. The ice-cold wine of this discovery I had warmed to the perfect temperature as I presented my own argument on why you will not die.

Brain functions don’t stop all together,

all in one snap moment of time.

They fall away, one by one,

as the last drops of blood deliver the last oxygen to each part of your brain.

Your biological clock is not the very last thing to stop.

Your sense of time disperses during your final moments;

thoughts, dreams, intuitions, impulses rage without a beginning or an end.

And in that simmering — you’ll live forever.

Easy.

The inflammation at my neurostimulator made me uneasy. A battery in my back, wires under my skin — was this experiment still tolerable? By allowing electricity to play inside my body, had I violated its integrity, its dignity?

II

Two days earlier — I woke with a shock. For some time I’d felt something stirring near the little device: an itch, a faint throbbing, the skin red in the mirror. Now suddenly I was awake, probably — I wasn’t myself. Panic was inside my head, and it took over, turning my brain into an autonomous engine. My arms locked around my chest, I rocked to and fro. A slice of moonlight fell across the room — the walls and ceiling moved, collapsing toward me. It is inside me. It is stuck. I cannot get it out. I was afraid, the fear ruled me. No control, my thoughts turned in a wheel, spinning faster and faster, and I — I? What was the I at that moment? — could not stop spiralling.

It is inside me. It is stuck. I cannot get it out.

I fled the bedroom, into the study, sat on the floor against the couch. Nice, colder, I could feel my body — I was still here. But I wanted to flee, had to flee. My body screamed: Run!

Then another sensation: my chest seemed to explode. It burned. Hot blood surged to my skin in boiling waves, while I shivered as well, ice-cold. What was happening? This was physical. My mind unraveled scenarios — everything that could go wrong with the battery and its wires. A leak. Electrocution. But it was the thing itself, the fact of its being in me, and me not being able to get it out. I’d done something irreversible.

I got up, wanted to step outside, but halfway I stopped. To reach the door I’d have to pass the kitchen — but not past the kitchen! A knife flashed before my mind, knife in skin, in scar; I would take it from the drawer, cut myself open, rip the whole technology out of my body, and I wouldn’t be able to stop. New fear piled on the old. I, who was I? The bundle of panic or the one trying to control it? My knuckles hit the device; if it dented, they’d have to remove it at the hospital tonight.

Desperate, distraught, deranged, my thoughts circled. I cupped the battery and tugged softly, already testing if the scars would open easily. Could I tear the wires loose — and then what? Electrocution? What would happen if I went to the ER and begged them to cut me open? They’d refuse. But I could force it — tell them the device was leaking, a danger. They’d have to take it out. It had to go. Something was inside me. I imagined my hand plunging into the bloody flesh, pulling out the metal pack — like the videotape disappearing into a stomach in Videodrome. Didn’t I have a doctor friend? She’d help. She must have a scalpel — at home, somewhere in her bag.

How could I have been so stupid? A computer in my body. Electric currents in my head. And now it was inflamed. A leaking battery perhaps. The arrogance! Like Prometheus I’d overreached — stolen fire from the gods. And what became of him? A cliff and birds of prey endlessly tearing him open.

I shivered; I couldn’t stop the thoughts. Sweat poured, breath heaved, ever instinct screamed: Flee, Flee! But how to flee? I was a dog chasing its own tail.

The Dutch sociologist Johan Goudsblom says it’s fire that separates humans from all other life. Only humans know to gather wood, light it, and keep it burning to stay warm, cook a meal and keep the wolves away. This human had stolen the fire and now it simmered in the battery in my back. But it was my reptile brain that told me to run from it.

I was human and salamander.

III

This panic attack was something else. It didn’t vanish after an hour like the headaches. It hit me in waves, but didn’t really diminish. During the morning, though, I found a remedy: I managed to redirect the anxiety into productivity. Sympathetic nervous system slowed down, writing speed went up.

A manifesto.

I’ll be damned if the anxiety attack wasn’t wired to the AI euphoria sweeping the planet. My Promethean connection wasn’t unique — the tech bros liked to summon him too. Silicon Valley was already drawing up plans for a 135-meter Prometheus to rise from the Bay, one and a half times taller than the Statue of Liberty.2

I was a cyborg, but a pathetic one: battery, chip, a few wires. The remote control ran on AA batteries. I wondered: had I gone too far, letting electricity in? And I thought of the AI-craze, building artificial minds, playing around with human dignity.

I went full philosopher on it, lambasting mankind for the hubris of creating artificial intelligence. And with my feverish head I uncorked another bottle. I’d defend humankind! Prove that AI would never understand humans. Ha! Could AI be human and salamander at once? It couldn’t even get properly drunk.

The believers infuriated me — all their talk of data, of everything being measurable. Heartbeat, sweat, eye movements, fear, rage — all, they said, recordable and very soon reproducible. They sold the future like a time-share flat.

I met a neuro-engineer from San Francisco, co-founder of two start-ups that tried to « upload » the brain to a « platform ». I accused him of theft, of stealing the soul. He smiled. « You can measure systems, » he said, « You can imitate without understanding. »3

He drew a box, arrows in, arrows out. « Whether it’s brain or computer, who cares? If you can predict input and output, the rest is noise. »

I asked if he wasn’t afraid of unleashing unknown forces. What could go wrong? Well… yeah, some moral shortcuts taken under pressure maybe. Others had started out with the best intentions, but later been forced by shareholders to take different directions that perhaps were not entirely, or not at all, bothered by morality, but that were chosen because the investment had to be recouped.

« I exist outside of these lines! », I shouted. Beauty is not just in my brain, it is a physical experience. Fingers touch and feel the bass guitar that brings sound to the ear and vibrations in the body.

I loathed the reductionism. A human is not the sum of data you can measure. That night I knew I’d be a knight, pulling humanity from the claws of the algorithmic know-it-alls.

The skin around my little casket was hardening. Was it leaking? Tomorrow — hospital. But first: my MANIFESTO! Yuval Noah Harari, David Graeber, Fukuyama, Žižek, and the rest of you wankers — here I come.

Humanity invented stories to explain its existence.

It replaced God the wizard with the magic spell of genes.

DNA became man’s cryptic code, copied down the generations.

As bacteria ate the flesh around my neurostimulator, I dug through books and theories, chasing one grand conclusion. In the morning I found, on my screen, words about « the essence of being human, the kernel, the inimitable secret of life, » it was supposed to lie « between opposites, between the measured data. »

Sounds vague, right? Bear with me.

The ride to the hospital lived in my muscles. I’d cycled it so often that I no longer needed to think. A simple straight ahead from my part of the Amsterdam grachtengordel, and automatically left into a tree-lined street. This trip held hardly any mortal danger: no roadblocks, no checks, no risk of air raids or snipers. Still, my reptilian brain kept registering parameters — scanning weather, cars, light, time of day, other cyclists, the position of my body on the bike, the fit of my clothes, fatigue, lust.

The sky was framed by treetops and the façades of the tall, mismatched Amsterdam houses — so many of them crooked that you couldn’t tell which leaned on which. A ray of sunlight struck my bike bell and flashed into my eye. I looked at it — what was that thing on the side called? The little lever you have to press with your thumb to ring the bell. A small piece of iron curled at an angle. I wanted to think about my manifesto, but the thought wouldn’t leave me. It had been with me for months — every time I got on my bike. Almost every time I grabbed the handlebars, I thought: does that little thingy have a name? But is that even thinking? Doesn’t thinking imply more activity?

Why these superfluous thoughts? The ones that bubble up during routine acts. Chopping onions? Always that question: are onions the only vegetables that make you cry? Matchboxes: again and again — how many matches are there in a normal box? Or the vague ones. There is a street where I always feel sad at a particular bend. No memory tied to it; maybe I forgot. Or maybe somewhere, once, I was sad when the light fell in the same way as it does in that bend. How much do I feel without knowing why? Is that still feeling? And where do all the images come from? When I was working on the manifesto, the little forest where two friends live would appear in my head. No idea why. What’s stored in my brain? Not much, haha — but how large is my memory? How many giga or terabytes? Sometimes a long-buried fragment rises up. How many are sleeping there?

— Picture it, now: what did the entrance to your primary school look like? What color was your front door then? Was there a doormat? What did it look like? And the shoes you wore in the final year — can you see them? Is the memory there, or not there, or there but out of reach? —

Sunbeams in my eyes. Heat, light. And the moon, pale as stone — that rare beautiful sight by day: a grey planet with relief and shadow. You could almost zoom in, see the craters, the flag planted by the Americans. If the flag toppled, I’d see it 1,3 seconds later. I squinted. Through my lashes, I looked toward the sun again — 8,3 minutes away. The blurred yellow I saw now was an image that had travelled eight minutes and twenty seconds through space. I saw the past.

I stopped, wheeled my bike onto the pavement.

It had to work the other way too, right? If someone stood on a planet as far away as the sun, they’d only see me pulling my bike up here 8,3 minutes later.

How did that trail of images exist? If that person closed their eyes, would the trail vanish — just because two eyes had shut somewhere in the universe? No.

So… so… draw a line to a planet a lifetime away — someone there would see your whole life stretched along it, every instance shining, from your birth to your death. Even after your death, you’d still be there on that line in space.

Wow.

I gave the planets the finger. Who knows — maybe someone saw. No. Stop. People would think I was mad.

From the past night I vaguely remembered leaping through the history of the algorithm. How wild — that humans had translated a chain of zeros and ones into electrical circuits — converting numbers into electricity. Representations representing representations. But could zeros and ones hold everything? Even language can’t. Take music: notes become data — 0s and 1s — yet their togetherness creates something beyond the numbers. The difference between sound and music.

Smart-asses had reduced all to a single unit: the bit — the information that something is either 0 or 1.

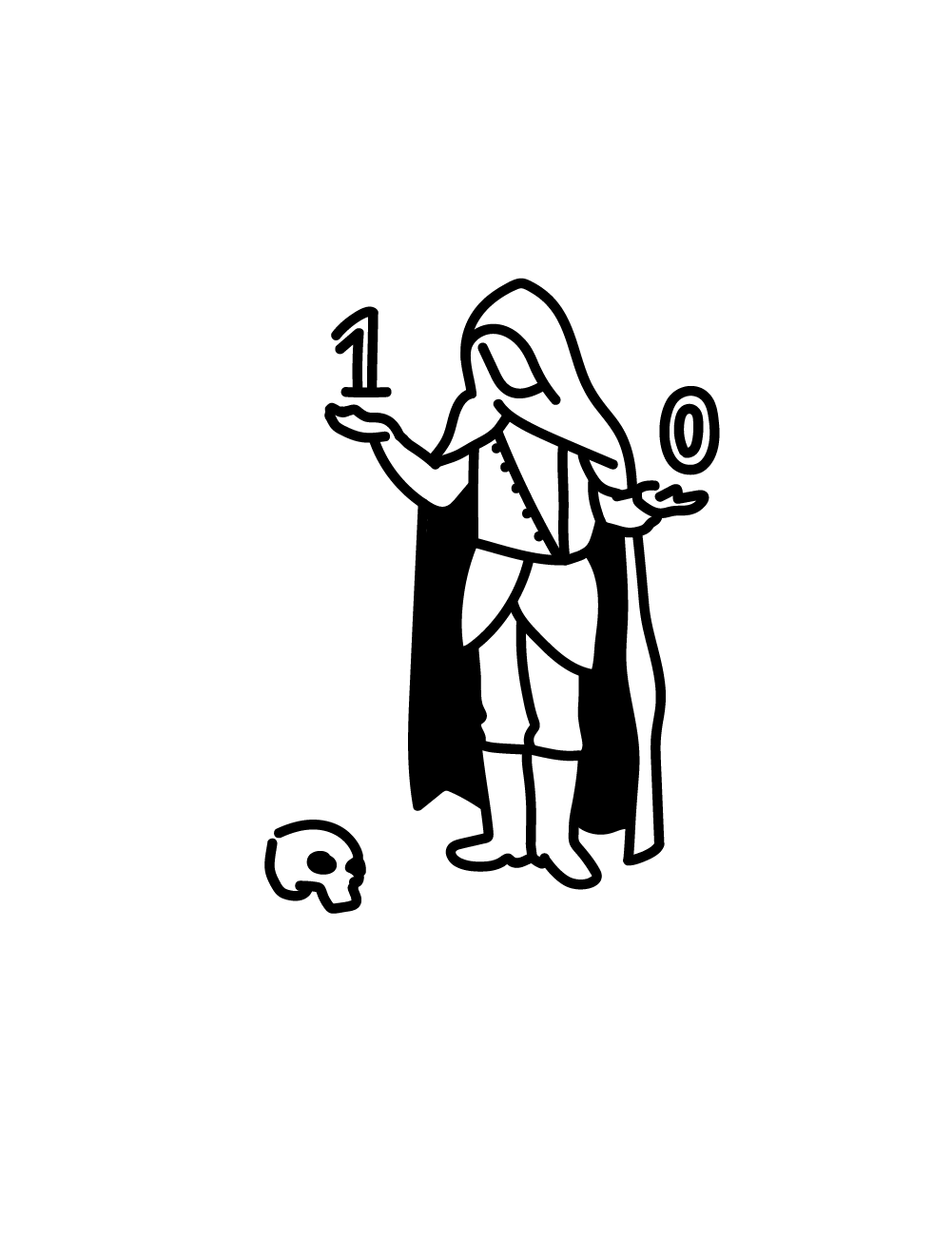

Beside my keyboard I’d found sketches:

Bit = 1 or 0.

Bit = to be 1 or to be 0.

Bit = to be 1 or not to be 1.

To be or not to be!

I’d found something! If X is the opposite of Y, they are bound by a relation — something is going on between them. For Hamlet to be means because not to be exists. That’s where it — the bit — fails. In a computer’s transistor, to be or not to be, is split: 0 or 1, one erased, the other survives, but stripped of its opposite. The unmeasurable between — dumped, destroyed. Woohoo! Human thought couldn’t be captured coldly in ones and zeros.

V

I couldn’t breathe. My feet were under a sheet. I was lying in a bed. A nurse passed by, then another. Other beds stood in the space. I couldn’t breathe, but my eyes were open and I could see the nurses moving around. I was breathing, yet I couldn’t get any air. I wanted to speak but didn’t. I wanted to move but couldn’t. I couldn’t breathe.

A nurse looked at me; I widened my eyes. She came closer and touched me. Still no breath. I managed a gesture, my mouth open. She clipped a plastic sensor on my finger and a blue light glowed.

« Your oxygen saturation is a little low. »

« I can’t breathe. »

« I’ll get you some oxygen. »

She turned away, returned, checked again.

« Oh, look, it’s rising — ninety-six percent. »

I could breathe again. Relief flooded me. Everything had gone well. The neurostimulator had been removed. I shifted my hips a little — yes, maybe I felt the absence.

« You nearly electrocuted the surgeon, » said the nurse. « It was still on. »

« No way, I switched it off. I was told to. »

The surgeon appeared, and I showed him the remote control — I’d kept it. Shockingly old-fashioned: a clunky box running on two AA batteries. The remote said off, but the surgeon insisted it had been on. That confirmed my suspicion: my reptilian brain had been right all along.

I went home and took it easy for a few days. Back among my zeros and ones, I found a German philosopher who had inspired the Dadaists with his Schöpferische Indifferenz: creativity arises from between opposite poles. Without necessarily comprehending the totality of his concept, I found this play of oppositions in the contrapuntal music of Stravinsky, the juxtapositions in poems of Apollinaire and Cendrars, syncopated jazz rhythms, the montage of Eisenstein, the Suprematism of Malevich… They’d already known back then, these guys. Humanity was a constantly creative process of Schöpfersiche Indifferenz: place a 0, put a 1 next to it and infinite worlds arise. I turned my Manifesto into a novel with a contrapuntal rhythm, but clearly did not succeed in changing the world with it. The tech boys enrolled ChatGPT, Claude, Alexa, AppleAI, MetaAI, Venice, Perplexity. Hope sparkled when my (Dutch) novel appeared on a list that had been fed to Meta for training its AI project, but, alas, it did not make AI reconsider its existence.

VI

This summer my inner warrior was kissed back alive by an unlikely figure: the Pope. Two days after his election, the new Pope addressed the College of Cardinals and explained that he’d chosen his papal name in honour of his predecessor, Leo XIII — the Pope who famously called for social justice in the wake of the Industrial Revolution.

In his 1891 encyclical Rerum Novarum, Thirteen had laid out the rights and duties of workers and employers, insisting on fair wages and the right to form unions. With it, he established the social doctrine of the modern Church.

« In our own day, » Fourteen told his gathered cardinals in 2025, « the Church offers everyone the treasury of her social teaching in response to another industrial revolution and to innovations in the field of artificial intelligence that pose new challenges to human dignity, justice and labor. »

Okay…

I dived in headfirst. It turned out that Pope Leo’s predecessor, Pope Francis, had already paved the way — defending human intelligence against artificial intelligence.

At Francis’ initiative, Microsoft, IBM, and others had signed the Rome Call for AI Ethics, a document advocating an ethical approach to artificial intelligence. And on 28 January of 2025 appeared Antiqua et Nova; On the Relationship Between Artificial Intelligence and Human Intelligence, a note commissioned and signed by the Supreme Pontiff, Francis.

From its opening statement, the Vatican left no doubt about whose territory the boys from San Francisco had wandered into: « The Christian tradition regards the gift of intelligence as an essential aspect of how humans are created ‘in the image of God’ (Gen. 1:27). »

The Vatican has been pretty consistent on this over the past few centuries: science is not wrong, it’s part of humanity’s ongoing development. Science, technology, arts — all proper forms of human endeavor. Together with God these humans on earth are only improving creation.

I bet you the Christian God wouldn’t have left Prometheus hanging like the Greek one did.

But in 2025, technology was attempting to imitate the intelligence from which it sprang, and that « epochal change, » said Antiqua et Nova, raised the question: what does it mean to be human — and what is the role of humanity in the world?

For the Vatican, the full breadth of human experience includes a lot of stuff that’s difficult to measure. They name « abstraction, emotions, creativity, and aesthetic, moral, and religious sensibilities, » which, to me, seem quite hard to pin down in 0s and 1s.

Never had I expected to find so many of my vague thoughts formulated by the Catholic church. Antiqua et Nova stated that AI wrongly assumed « that the activities characteristic of the human mind can be broken down into digitized steps that machines can replicate. »

AI is not a form of human intelligence, but a product of human intelligence: a tool, not a replacement for humans. It can perform tasks, but it cannot think in a human way. Humans are body and soul, matter and spirit — deeply connected to the world and exceeding it, in, for example, the bond from one person to another. Here human intelligence expresses itself through love. A friend knows the right word to say — and not by logic.

AI, the Vatican insists, is fundamentally different from human intelligence, which is embodied, emotional, social, and moral.

Fourteen continued Francis’ work on AI. In the summer of 2025 he declared that a human being, with its « openness to truth and beauty » cannot be confined within a soulless machine. A new encyclical is expected.

VII

I still have the headaches — had a few while writing this — twice a day, sometimes more, sometimes less. They’re nicknamed « suicide headaches » because people start smashing their heads against walls, or worse. I don’t. I take all kinds of medication, inject myself, and usually the headache’s gone soon after. Sometimes it lingers.

The neurologist gave me a book. Pain is a signal, it said. But here, the signal has no source. It’s instantly there — in the hypothalamus — out of nowhere. My nose runs, my eyes flood, but I know: there’s just the signal, no cause.

On days when the pain stayed longer, I found myself browsing through Vatican texts. Once, I’d have dismissed a signal from the Vatican as a signal without a source. Now I was intrigued by what happens when there are no causes.

The word « dignity » kept appearing. Human dignity. I’d begun to notice how often that word appeared whenever people talked about Big Tech and AI, as if they endangered human dignity.

Antica et Nova put it like this: « A person’s worth does not depend on possessing specific skills, cognitive and technological achievements, or individual success, but on the person’s inherent dignity. »

And, it adds: « Human dignity and the common good must never be violated for the sake of efficiency. »

Human dignity — the recent winner of the Dutch election, a left-of-center guy, used the phrase in his victory speech. New York’s new mayor Zohran Mamdani, keeps returning to it. In Google’s gigantic corpus of digitised books the combination « human dignity » has risen sharply since the 1990s, when globalism took off and people increasingly found themselves treated more as consumers than as citizens. Lately the growth has stalled a little. And now here’s a sentence I never expected to write: I trust Pope Leo XIV to defend humankind — body and all.

- It even found its way into a novel (published in Dutch), from which I am happily plagiarizing here. ↩︎

- In the plan Prometheus is called THE ARCHETYPAL AMERICAN SYMBOL: « His symbol also profoundly describes the Bay and its technology leadership, which is the spearpoint for Western leadership of the technological future more broadly. There is no more fresh, vital, and inspiring figure than Prometheus for the future about to unfold and the Renaissance in which we must embark. » See: www.americancolossus.org ↩︎

- See our essay by Philippe Huneman, « Without cause », in ERB Issue Six, in which the French philosopher writes a philosophical review of the EU AI act and concludes that a reality is emerging in which causality is driven to the background. ↩︎