A story about traps

Translated by Joana Frazão

1. The border

Yes, Europe — but the border considered the longest is the one between Canada and the United States (6.416 kilometers). The shortest one is between Gibraltar and Spain. It’s called La Línea (the line) and measures 1.53 kilometers. And the Book of Curiosities also states that Zimbabwe, Zambia, Botswana and Namibia all « come together at a single point ». The thing is, this book is probably already out of date, but it’s interesting that a geometric point, a point you can mark in pencil on a piece of paper, despite its tiny size, can be the point (in pencil) where four countries meet. And all the second Savior of Europe wants, deep down, is to mark a point on the map that is common to all countries — all of them, my dear. And of course, you can call this point God, but that would be too easy. Nor is the point invisible or psychological; it’s a geographical point, a point on the earth’s surface that belongs to all countries, and therefore has no owner, no army looking after it. It belongs to the second Savior, who wants that point so all humans can meet there as good brothers. He doesn’t want a tower, he doesn’t want a building or many square meters where he can jog, he simply wants a point the size of a pencil dot on a piece of paper, a circle less than a centimeter in radius. And such lovely sentiments are to be commended, though it’s physically impossible for the crowd to gather at a point on the earth less than a centimeter in radius. Not even two friends, nor a wife and her husband, nor even a mother and her child will be able to come together at such a tiny point in space. That is why the second Savior of Europe is once again deceiving the peoples who so desperately want to be brothers. The point where all countries come together is, in fact, a trap.

And in that Book of Curiosities, it’s also said that the border most crossed by humans is the one between Mexico and the United States; a great deal of traffic on that line, as if on both sides there was an incomparable disquiet. But in fact, the real border most crossed by humans is the one between being alive on one side and being dead on the other. And the question is: where is that line (the real Línea) that separates the living from the dead? You’re walking around and bam!, you’re on the other side; you’re sleeping and bam!, you’re on the other side; a bullet hits you in the head and bam!, you’re on the other side.

It is a border with a one-way crossing, unless you believe in strange events. Sometimes, sometimes a man takes a bullet squarely to the head and bam!, strangely enough, he doesn’t go to the other side, doesn’t cross the border line, still remains in the world of the living — and what’s more, in addition to breathing, he still moves and talks and thinks. And in this case, the man with the bullet in his head, in addition to moving and thinking, still experiences curiosity, excitement, and a bit of desire, and so he moves forward, goes someplace else, does things, helps build the tower that the second Savior of Europe doesn’t want built. There he is: wanting to be human, wanting to be human at every time and every place in the world, human to the end, this man with the bullet in his head deserves a medal.

2. The wall

But, of course, there is the Wall. The men who speak differently and who bow differently and who hold their hands to their chests differently, those men cannot touch the Wall; it’s forbidden for even one of those men to lean against it because they say that these men work like the black rats of the plague: if they touch the Wall, they will contaminate the Wall, and lo and behold, this Wall — a strange, almost magical Wall — separates the people who are on the same side, it doesn’t divide one side from the other; no, on the contrary, it divides the same side into many little pieces. It divides by movements: those who make certain movements with their hands can go near the Wall; those who don’t, those who do not know these movements, cannot go near the Wall. Some can touch the Wall, with their hands, with their foreheads, others cannot touch the Wall; their hands will be cut off; if they touch it with their foreheads, their heads will be cut off.

3. The cage

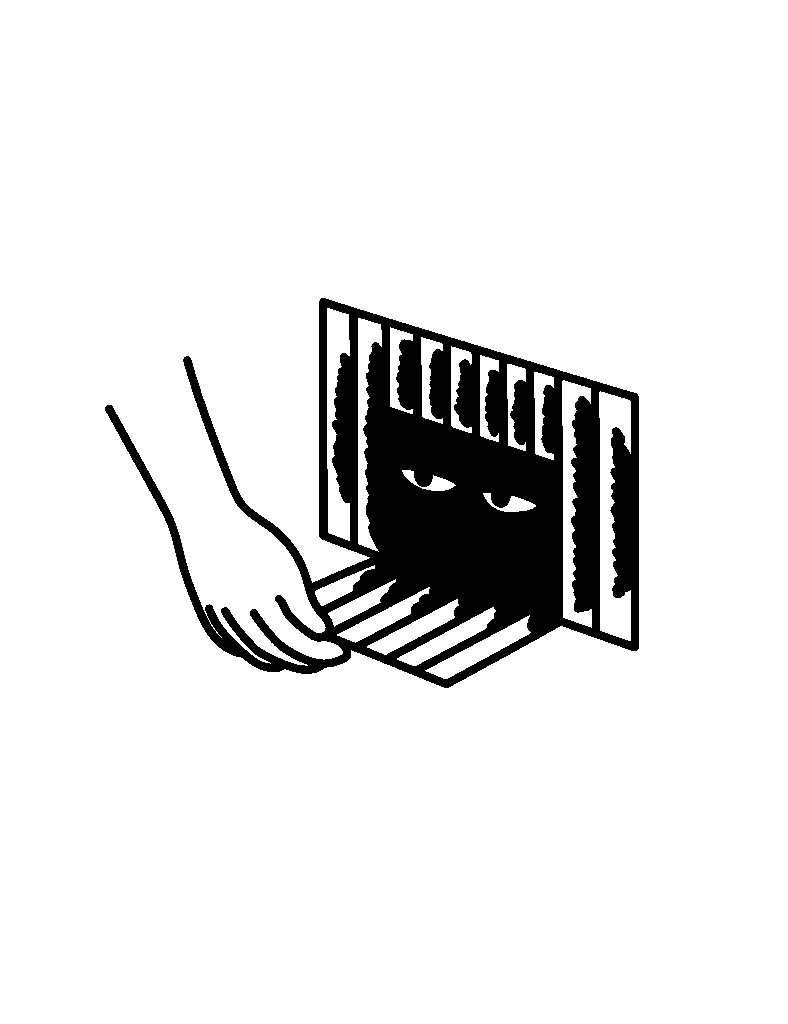

A beautiful person is trapped in a birdcage, a tiny half-meter birdcage, and those dimensions force the beautiful person to bend over themselves several times like a circus contortionist, or to fold onto themselves like an inert blanket, and so the beautiful person is mistaken for a monster that wants to be displayed in the birdcage, or is comfortably folded. We must draw conclusions from this story — for example, that the beautiful needs a certain space in order for what is folded to unfold, since only then, in its full extension, does the beautiful cease to be beautiful only for itself and become beautiful also for others, for those who behold it. That is why some people make a suggestion to the hunters of the monstrous: let the monstrous spread out, expand, let the monstrous take up all the space it desires, for only then can you be sure whether the monstrous is just that — monstrous, terrible — or whether, after all, it’s the beautiful that has been forced to exist in the tiniest dimensions of space. So let the monstrous grow (if we now move on from shape to morality), let the moral monstrous grow, for surely when it has invaded everything, the houses in the neighboring town, the houses next door to yours, and finally your house, your living room, your bedroom, your children’s bedroom, when the terrible has unfolded completely, when it has flooded the largest possible area, then yes, you will see that horror, when it says, « I am satiated », can seem — seem — beautiful. And yes, you will have lost a lot, the tragic inventory includes people you loved, that’s quite right, but you will have confirmed that you weren’t being unjust: the moral monstrous was truly monstrous. It wasn’t the beautiful all folded up in a birdcage. Hence the aesthete’s great temptation: always to allow, never to prevent the hypothetical power of the beautiful from manifesting itself: let horror continue on its way, let us not get ahead of ourselves, let us never be unjust, we can never know how something ends before it ends, that is evident, let things occupy their natural extension!

4. The swimming pool

The dictator, for example, is by a pool that was built for little sharks to become, over time, adult sharks. And Stalin has taken off his shoes and socks and sits there, by the pool’s beautiful blue water, soaking his two sacred feet. No shark will come near them, and Stalin has time to count the scary animals. There are three, four, five. Beautiful teenage sharks. The dictator is not a little boy, he has a lot of jobs to do today, but he is entitled to his laziness, his leisure, his boredom. Feet in the pool, which is twenty meters by fifteen. Five sharks, two human feet swinging back and forth as if they belonged to a little boy. It’s an almost bucolic, pastoral picture, water, animals, a man savoring everything that passive nature can give him. The only reason the dictator doesn’t pull out his fishing rod is because even the most morally wrecked animals harbor a certain pride. In any case, each of those animals has its own name and they all have their father, the most beautiful father of all, whose toes, sooner or later, they will end up eating, three at a time, or four, and then all the way up — above the heel.

5. The bullet

The bullet that is in the head of the man with the bullet in his head must be blessed, just as cannons and all ammunition are blessed before battle. Of course it’s strange, this T-shaped blessing motion, made in mid-air, in the void. And the man with the bullet in his head is going on a journey, he will try to make the bullet dissipate through movement; perhaps through speed the metal will start to dissolve, the accelerations will make the metal break into several parts, and those parts into different parts; perhaps even the bullet’s metal, when very much divided, when very much broken and dissolved, will turn into a cell, a tiny part of the organism. The man with the bullet in his head is running a 100-meter dash, doing repeated 100-meter dashes as though he were training for an Olympic competition. What he desires is that the start, the burst of acceleration, and then the sustained speed will transform what is now the death threat lodged in his head, the bullet, into porridge for children.

Naturally, there are doctors who do not recommend such sudden movements, as the bullet, instead of dissolving, might simply move ike a car that has run out of gas but coasts forward, by inertia. Inert things might still gain momentum, for example vertically, and you might now think of a car without gas, being pushed by ten strong men towards the edge of a cliff, and then, just at the moment when the car without gas begins to fall, from a height of over a thousand meters, at that precise moment, the engine might, let’s imagine, come to life again, and instead of tottering forward, the car would take flight.

6. The ear

Animals adapt to the cold. The ears of hares shrink as the temperature drops, thus reducing heat loss. The exile (hotel, room 66) could have solved things that way too: the cold seeps in from under the door and through the windows, which are badly fitted to the wall, like stickers, placed there forcibly to patch or heal the wall — but a window isn’t meant to heal, it’s meant to allow those inside to look out and, please, not let too much cold in.

The truth is, the exile is shivering, even with the blanket he’s dragging around, and the doctor enters room 66 — there he goes, on his hind legs, with the traveling science perched on his neck — and asks the exile to stand, he wants to measure his ears, to see if the exile can adapt like the hares near the polar circle. But his ears refuse to cooperate with the measuring tape that the doctor carries rolled up in his pocket. The exile’s shivering ear is the ear of a normal human being. And the diagnosis is made: akathisia — « the inability to sit still ». « A slight restlessness » is entered into the report, « a muscular impatience ». The exile paces around the room. Such is his illness, the doctor thinks: the exile puts all his weight on one foot, as if rehearsing a technique, and then hops to the other. If the exile were thrown into the street, he would be lost in no time, because he won’t sit still. Luckily he has a room, it’s locked from the outside. The doctor has thought before about installing a wheel, like the ones used in rat cages, yes, but it would be larger, and might soothe the exile who shivers with cold.

Mammals’ and birds’ cold feet allow them to withstand frozen ground. The rest of their fur-covered bodies allow them to withstand the wind. Sometimes soldiers come back from war with cold feet, while the rest of their body stays warm. They say it’s the fear that has settled in their feet. Humans, animals, plants and soldiers are equipped for anything. But death does sometimes come. And for that, there is little preparation.

7. The pickaxe

This often happens: ice suddenly forms and covers a large body of water. There are animals that need to come to the surface but cannot.

The man with the bullet in his head moves carefully over the ice, making sure not to fall; he wants to be good, the man with the bullet in his head thinks, and he wants the good to have no weight. In order to muster courage, he tries to make his weight vanish with sheer good will, he carefully moves across a thin layer of ice that shouldn’t hold his seventy kilos, and in that moment, when he feels good (because what he wants is to cut a hole through the ice so the animals can come and breathe and not die), he does have the sense that his body has suddenly become light, the weight of his organism has vanished, that he’s an angel, after all, and the only thing that does have weight, up there in the middle of his head, is the bullet, moving forward with almost no support, with no legs beneath it. It’s as if this bullet, at 1,78 meters above the ground, is what measures the height of humans: we speak of below sea level, above sea level, and now, when the man with the bullet in his head inches forward across the layer of ice, we can also speak of below the level of the bullet (1,78 meters), above the level of the bullet.

Above the level of the bullet there is the sky; below, there is ice (not earth) and that’s where the man with the bullet in his head is, using a pickaxe to break through the ice, trying to focus all his weight on his arms, without putting pressure on his feet, shifting the weight away from his center of gravity, and there his arms are working, a little ahead of his torso, as if he were a farmer digging a hole in the ground, that’s how he feels; but he’s more than a farmer digging a hole in the ground, he’s a man trying to dig a hole through a layer of ice, and he’s succeeding, for he has already made a small hole, a few centimeters in diameter, which grows larger with each of his blows, and down below you can already see a tiny patch of water. And thus he’s a farmer who saves those who are buried underground, or under ice (treacherous ground, dangerous ground, the true identity of ground: the ground cannot support the selfish weight of men, one might say), and because the man with the bullet in his head is doing good, he has no weight, which is why he has managed to make a hole. The circumference is rough, misshapen, because it was made with a pickaxe, there’s no way to execute a perfect circle when the goal is to save; the fact is, that misshapen circumference has already saved many animals, including some belugas, for example (Delphinapterus leucas), two of them, who were moving under the layer of ice until they found salvation, that’s what this is all about, some belugas finding salvation through that misshapen circumference, hacked out with a crude pickaxe; and here we see how the pickaxe saves more than the compass ever could, although the man with the bullet in his head isn’t satisfied, and after the misshapen circumference, he still wants to cut out a perfect circle, for he likes and has learned to create perfect circles.

And so there he is, bending carefully over the ice, and with a compass that he has pulled out from his jacket, he traces a perfect circumference on the layer of ice; a geometry nut who draws a circle in pencil on a layer of ice, and with small strokes he tries to break that layer while preserving the circumference, but of course he fails, the ice does not obey the line drawn in pencil, which is no surprise, only a madman would expect natural ice to obey such a fine line. Even so, he doesn’t give up: he has already made two holes, two misshapen circles — not even circles, they’re shapeless holes — and he’s not satisfied because animals should not be saved by imperfect shapes, by holes made with a pickaxe or with human fists. So he has the compass in his hand again, and the man with the bullet in his head now attaches a blade to its tip, which before had only drawn a line in pencil, and thus to trace a circumference with the compass is now to cut and not to draw. This good man has abandoned drawing, for he has realised that drawings don’t save the way he wishes they would; so he has moved on to cutting, and that is what the modified compass does, a slow cut, circling around itself like it should, moving forward until it completes its path and returns to the starting point, and finally on the third attempt he succeeds: the beautiful circumference of ice removed from that huge layer, covering many kilometers of ice territory, and any animal that comes to breathe through this perfect circumference, that animal will be saved, it will befriend the man with the bullet in his head, each animal that now appears with its snout at the surface is pulled out of the icy water by the man with the bullet in his head, like a man looking after the shipwrecked, pulling those who were drowning onto solid ground (well, more or less solid ground, after all, since it’s a layer of ice we’re talking about), and by pulling them out of the icy water so they can breathe, he sometimes kills them, because some animals are meant live underwater, in a liquid environment, and not on top of the layer of ice.

Nevertheless, the animals, even under the layer of ice, communicate with each other, sharing the secret, because after a short time, after just a few hours, the animals that need to breathe above the water stop coming to the perfect circle, they stop coming to the circle out of which they know they will be forcibly taken, taken out of the liquid medium against their will, and instead they head, yes, all of them, to the circles made with a pickaxe, to the misshapen circles, to the shapes that waver between circle or square; and the man with the bullet in his head, who wanted so much to save, now has no more animals to save, but his kindness has already proved useful anyway: many animals are breathing now thanks to the work of the pickaxe that destroyed part of the ice, in tiny little holes. A savior farmer, behold the man with the bullet in his head, trying once again to concentrate on his kindness so that he remains weightless.

This story was commissioned as part of Liquid Becomings, the European Pavilion 2024, a program of the European Cultural Foundation curated by Agora Now and partners.