The afterlife of Germany’s lost book collections points to the complexity and the promise of a common European culture.

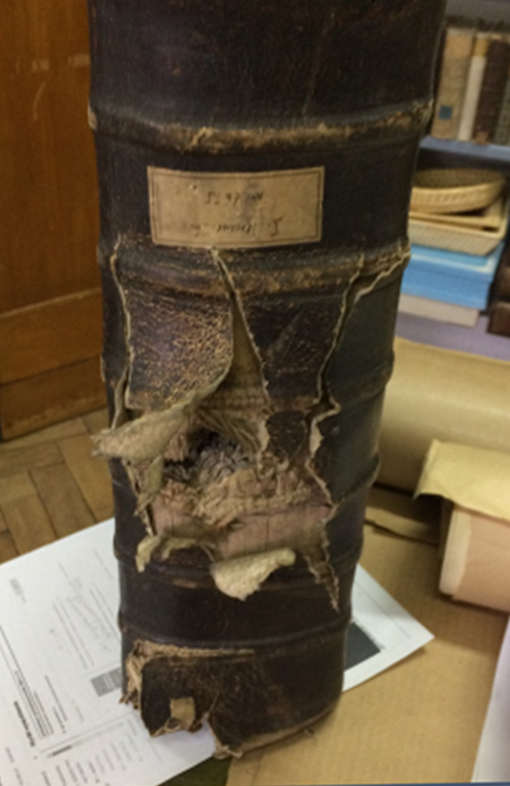

The Bible isn’t listed in the catalogue. If it were, its bibliographic description would probably read: « Illegible date, post-1650, large folio format, wooden binding, metal clasps, German Gothic, printed in two columns, Luneburg. » The book has a bullet hole in its spine. Was it caught in the heat of hand-to-hand combat? Did it save a life?

This bullet-pierced German Bible is housed in the University Library of Łódź (BUŁ), a city in Poland 120 kilometers southwest of Warsaw. It is kept in a room that the University librarians informally refer to as « the Hidden Treasures Room » — a special collection dedicated to prints published before 1800. The room, dark, airless, is filled with shelves arranged in narrow aisles and overlooked by a gallery only accessible by ladders. It’s not a place one stumbles upon by chance. In this ancient book room, the oval labels affixed to the spines are mismatched, reflecting a patchwork of different classification systems. Many books still bear the former marks of the institution from which they originally came, with the stamps’ designs remarkably diverse and eclectic. 78% of the books in the University of Łódź’ Special Collections Room came from German collections, both private and public. Before the war, some of these books were located in Silesia or Pomerania, provinces that had been Prussian for centuries and then in August 1945 were transferred to Poland. Others were moved from Berlin, from the former Preußischen Staatsbibliothek as well as the Stadtbibliothek. Covered in a thin layer of dust, the volumes often have trimmed corners and pages marked by humidity stains or pierced by bookworms.

I first discovered this room when I was researching the vanished Bibliothek Schloss Plathe, a library that was founded in the eighteenth century and housed in a castle in East Pomerania, situated in the small city of Plathe, between Stettin and Danzig (now Płoty, Szczecin and Gdańsk). It belonged to my German family-in-law before the war. Little remained of this former library: a few manuscripts, scattered books, but above all, the last catalog of the collection. It allows us to reconstruct the collection and its holdings. After March 1945, when the Red Army moved into Pomerania, the library’s 16.000 books disappeared–looted, carted back to the USSR, possibly destroyed. Some of the collection, it turned out, had survived and ended up in the University Library in Łódź. In 2018 — seventy-three years after their original dispersal — I found myself in the « Hidden Treasures » room, identifying volumes that had been pillaged — or rescued — from this eighteenth century German family library after the Soviet takeover. The books I was seeking from this lost library were not alone in their war-orphaned state. The room was like a time capsule. All its volumes were veterans of twentieth-century turmoil — like the bullet-scarred Bible, they stood upright in their shelves, surrounded by unfamiliar neighbors, torn from the coherence of their former collections.

You’re reading this essay for free. With a membership, you can read the full magazine, and you get access to our fabulous Library.

Here’s our offer: 3 months unlimited digital access + 1 print edition for € 38,00 € 19,00

You’ll get Issue Eleven in print as your first magazine, right to your mailbox.

The crypt

In the 1970s, psychoanalysis introduced the notion of the crypt to describe the difficulty of confronting a traumatic past. In L’écorce et le noyau (Paris, 1978, published in English as The Shell and the Kernel, 1994), psychoanalysts Nicolas Abraham and Maria Torok define the crypt as an « intrapsychic vault », containing emotions or memories that are buried, hermetic, inaccessible even to the analysand. The lost object gets incorporated rather than transformed, as the mourning process would require.

For later cultural historians and theorists of memory, « forgetting » does not stand in simple opposition to « remembering ». Memory reconstructs the past within a given moment, marked by context yet also by the distortions, gaps, and obscurities it inevitably brings forth. Archives and libraries, too, are places that preserve, but equally, they conceal and let fade. The crypt is thus this place of sedimented forgetting, a space of relegation. In Der lange Schatten der Vergangenheit, Erinnerungskultur und Geschichtspolitik (Munich 2006), cultural anthropologist Aleida Assmann distinguishes between forms of forgetting that conserve and forms that destroy: borrowing a paradoxical phrase from Friedrich Georg Jünger, she speaks of « the preserving of forgetting » (Verwahrensvergessen).

The metaphor of a hidden repository of deliberate forgetting recalls the German books and archives that found themselves on Polish territory after the borders changed in August 1945. For eighty years, these thousands of German books and manuscripts have rested in a frozen place, a crypt, in the very sense invoked by psychoanalysts and memory historians.

Talks between the GDR and the People’s Republic of Poland on the future of the books began shortly after the war. The two countries sought an agreement on the return of displaced cultural objects; yet, despite the much-propagated « Friendship of the Peoples » among the Soviet satellites, they made little progress. Each exchange — here a German Bible, there a Chopin score — seemed only to deepen mistrust and misunderstanding on both sides.

For the general public, the existence of these works of German provenance that had wound up in hidden rooms in state or university libraries across Poland was neither discussed, nor the provenance even indicated in catalogues. The subject was too politically sensitive.1 That handwritten scores by Mozart, Beethoven, and Mendelssohn had survived the war intact, and were now in the Jagellonian Library in Kraków became known only in the late 1970s, when it was revealed by a daring journalist for the New York Herald Tribune: Robert Carleton Smith.2 Until then, the matter was classified as « top secret ».

The fall of the Berlin Wall and the recognition of the German-Polish borders (The « Two Plus Four Treaty », negotiated in 1990, entered into force after ratification by both parliaments in 1992) seemed to offer an opportunity to resolve these points of cultural contention. A group of experts — lawyers, diplomats, historians — came together under the name « Kopernikus Group » to seek a solution, but once again nothing came of it. Against the backdrop of growing economic and political integration within the European Union, German-Polish relations over displaced cultural property seem to have been reduced to a series of misinterpreted gestures and missed opportunities, reawakening old resentment.

Time hasn’t eased the matter; on the contrary, in both countries, it has left the government officials grappling with an extremely delicate and complex issue. Why is it so difficult to move forward?

The Polish urn

In a palace annex of the National Library of Poland, where dark shelves carry rows of books bound in gold, the visitor’s eye is immediately drawn to an uncanny object: a cone-shaped, fragile mass. Is it some organ suspended in formaldehyde, borrowed from the Natural History Museum, or a wild honeycomb? Approaching the display case, we read the caption: « Urn containing the ashes of the National Library’s collections burned during the Second World War ». No artist’s name is mentioned; the object on display has no author. The destroyed books have lost their shape. Close up, you can see the remains of a charred leaf, bleached by time. Izabela Mrzygłód, who is part of a research project based in Warsaw entitled « Recycling the German Ghosts », emphasizes the fragility of this urn on display, which, to her, seems to be on the verge of disappearing completely: this image of an irreparably damaged book locked in a glass urn evokes feelings of « loss », « emptiness » and « silence ». It also evokes to her « the unheard Polish story. »3

The ashes contained in the urn come from the former Krasiński Library, deliberately set on fire in October 1944 by Nazi Germany. They were probably collected by the first witnesses to assess the extent of the damage. One of these witnesses, theater director Bohdan Korzeniowski who was then a librarian at the University of Warsaw, describes in his memoirs the burning of the collections as a « bibliocide », methodically organized by Nazi « incineration or extermination commandos » just before they left Warsaw.4 The destruction of the library was not collateral damage from bombing or street fighting, but the result of an ideological project to annihilate Polish culture, pursued since the beginning of the war with consistency and determination, by a « special book unit » (Sonderstab Bücher) of the Gestapo.5

The deliberate destruction of Poland’s cultural heritage remains a painful and vivid memory. A 1994 study by Barbara Bieńkowska, published under the auspices of the Polish Ministry of Culture, estimated that Polish libraries lost 70-75% of their collections. As librarian Alodia Kawecka-Gryczowa has stressed, grief is compounded by the impossibility of precise assessment, since the inventories and catalogues themselves have vanished. Writing on the history of the National Library of Poland, she speaks of « an irreparable loss [that] does not fade with time. »6

As for the rich Jewish libraries of Poland from Warsaw to Lublin, from Breslau to Vilnius (Wilna), community institutions, as well as private collections that were founded and enriched during the Jewish Enlightenment (Haskalah) of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, they were systematically destroyed from 1939 onwards, along with their owners and readers. After the German surrender, as part of their work for the Commission on European Jewish Cultural Reconstruction, Gershom Scholem and Hannah Arendt turned their attention to the surviving books from the seven hundred Hebrew communities that had existed before the war. Scholem and Arendt helped ensure that these works — « heirless », with no remaining readers — were made available to Jewish diasporas around the world.7

German war losses

In their extensive study The Library: A Fragile History, Andrew Pettegree and Arthur der Weduwen remind us that since ancient times, libraries have always been under threat of destruction. Yet no century has proved as devastating to their existence as the twentieth century. And despite its role as aggressor, looter and arsonist of books, Germany was not spared.

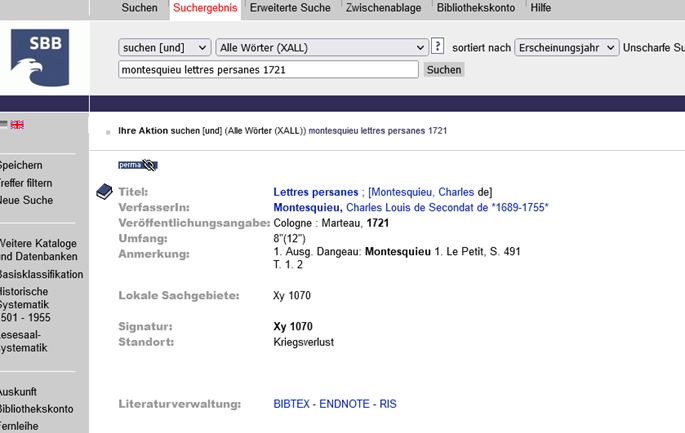

Although German commemoration of this loss is discreet, it does take place. When searching for a book in the electronic catalogue of the Berlin State Library (Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin), 80 years after the end of the Second World War, one may still be confronted with a strange warning. Take, for example, Montesquieu’s anonymous novel Lettres persanes, with its false place of publication, « À Cologne, chez Pierre Marteau », when in fact it was published in Amsterdam in 1721. In the electronic catalogue window, which usually indicates the book’s location within the Berlin State Library’s various storehouses and the estimated delivery time for the order, the reference Xy 1070 reads: « Location: war loss » (Standort: Kriegsverlust).

The book is therefore listed in the State Library catalogue, but listed as missing. Such references apply today to thousands of books from the collections of the former Prussian State Library. The compound word « Kriegsverlust » denotes what has been lost because of, or during, a war. In the pragmatic world of a digital catalogue, this term is somewhat surprising. Is it a « Stolperstein », meant to make the user stumble, so that even in the hushed world of libraries, the disaster of war is not forgotten? Yet something remains unclear in this catalogue entry: was the book burned, destroyed during the war, is it lost for good? Continuing the search on the website of the Berlin State Library, one is shifted into a legal register — less vague and poetic — that confirms that the search is ongoing, the case not closed as « lost for good. » We are told of ownership stamps (Besitzstempel und Supralibros); and now the note reads more like a warning: « The Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin claims ownership of all documents bearing its historical stamps. » The missing book might be somewhere. German librarians might even know for sure where.

From 1941 onwards, following the Allied bombing of Berlin, the Prussian State Library (Die Preußische Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin, PSB) decided to transfer its collections to the countryside for safekeeping. Lorries and railway carriages transported the collections, packed in wooden crates, in all directions, including eastwards. In Pomerania and Silesia, eleven State Library deposits found refuge in sheds, castles and monasteries. When the Red Army conquered Pomerania and Silesia in January 1945, the population fled in large numbers, but the collections evacuated from Berlin remained in place. At the Potsdam Conference in August 1945, when the German-Polish border was moved to the Oder-Neisse line, millions of books from private, ecclesiastical and public collections thus found themselves in a new national context.

Two irreconcilable narratives

From the Polish perspective, these collections of « abandoned and neglected » books are considered a national property under the law of 6 May 1945, which protects them from looting and destruction. In the Soviet Union, a « special mission » had already in 1944 been appointed. Its task was to supply, in addition to the libraries of Moscow and Leningrad, a Soviet literary fund (Gosfond Literarury). The loot is estimated at around ten million volumes.8 Poland attempted to prevent the transfer of « trophy books », including those from former German collections, to the Soviet Union. It also tried to prevent looting and destruction, and often succeeded. Collections from former German library holdings are thus referred to in Poland as « the secured collections » and, subsequently, « post-German » (poniemiecki) collections. As in the expression « post-modern », this construction signifies not only chronological posteriority but also a critical relationship to the object.

On the German side, in the field of libraries, the post-war period was marked by the immense task of clearing the rubble from bombed institutions and drawing up an inventory of remaining and missing books. Three million volumes from the former Prussian State Library after the war were initially considered « lost. » All this reckoning took place against the backdrop of the division of the two Germanies, which meant two state libraries, two competing institutions each with their own catalogues: the Deutsche Staatsbibliothek in East Berlin and, from 1963, the Staatsbibliothek der Stiftung Preußischer Kulturbesitz in West Berlin — institutions that were less than two kilometers apart, but separated by the Wall and by opposing ideologies.

Three years after the fall of the Berlin Wall, the two institutions merged and took the name « Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin — Preußischer Kulturbesitz » (Berlin State Library — Prussian Cultural Heritage). To combine the catalogues, they went back to the pre-war inventories. The director of the reunified institution made identifying war losses his main objective. In 1995, they published the catalogue of an exhibition on missing books. Its title Verlagert, verschollen, vernichtet… (Displaced, lost, destroyed…) strikes the note of a Baroque cantata. (The catalogue’s subtitle Das Schicksal der im 2. Weltkrieg ausgelagerten Bestände der Preußischen Staatsbibliothek — « The fate of the collections of the Prussian State Library transferred during the Second World War » is somewhat more prosaic.) In it, the author Ralf Breslau expresses his unwavering loyalty to the missing books, lamenting their « fate », a notion derived from Greek mythology which, in this case, sidesteps the historical context for their displacement and disappearance. Breslau’s particular focus is on the collections now in the Jagiellonian Library in Krakow including manuscripts and autograph scores by Bach, Mozart, Beethoven but it is above all the volumes about which nothing is known, the books that disappeared « without a trace » that seem most to weigh on his imagination. The catalogue highlights the « wounds », the emptiness, the « painful gaps, » the « lasting » damage caused to German collections.

In the following decades of the annual reports of the Berlin State Library, the lexical register becomes less emotional and more legal and technical. The loss of books is described in the administrative language that Germany has mastered: « kriegsbedingt verlagerten Kulturgüter », meaning « cultural property transferred due to the war ». Despite the initial euphoria surrounding Reunification and the first re-establishment of contact with Russia and Poland, the results have been mixed. In the 2006 annual report, the director mentions « war losses » and, above all, the confusion they cause in catalogues as a source of irritation that the institution would like to finally be able to get rid of.

Outside the institution’s administrative difficulties there persists a wider reluctance to move on, something akin to a refusal to mourn. The dispersion of medieval manuscripts, scores by Bach, Mozart and Beethoven, part of Alexander von Humboldt’s legacy, and the Heinrich Heine and Heinrich von Kleist collections remains a painful subject in Germany to this day. Rare pieces of lieder out of reach, scattered manuscripts, dispersed libraries… The manuscripts of the first, second, and fourth movements of Beethoven’s Eighth Symphony are held at the Berlin State Library, while the third movement, Tempo di menuetto, is in Kraków. As recently as 2007, Tono Eitel, then special ambassador for the « return of cultural property displaced during the war, » described these works as « looted » (Beutekunst) and as « the last German prisoners of war ». For how could a nation forget its prisoners?

Emerging from the crypt:

towards a European heritage?

Since 1945, collections from former German libraries have been the subject of two incompatible discourses. For Poles, the national narrative of their own destroyed heritage is one of loud, visible and emotional mourning, as exemplified by the urn of ashes exhibited at the National Library. Their attitude towards the displaced German books that have wound up in their libraries is summed up by the word coined to describe the artefacts — « Berlinka », the name of the German capital with the suffix -ka added. It reflects the Poles’ familiarity with the books’ history, but also a somewhat cautious irony regarding this neighbor who has not always been kind. The term is also a form of personification of the legal issue. Are the books claimed by Germany the equivalent of « little Berlin », a euphemistic diminutive that tames the horror of the thing through language?

In Germany, the discourse on war losses is more discreet, ambiguous and problematic. Claims for « lost » books are camouflaged behind legal paragraphs and in the interstices of digital library catalogues where no one thinks to look for them. Germany does not renounce its property rights, but it does not trumpet them either. In this sense, the subject also highlights an asymmetrical relationship with the history and memory of the destruction wrought in Poland by the Reich. While in Poland the « post-German » collections serve a memorial function, this dark chapter of the war of extermination waged in the East is less well known to the general public in Germany. Here, there is no personification of the problem of « lost » books, no affectionate or ironic diminutives, but, on the contrary, abstract, almost disembodied administrative terminology as a mark of the absence of books and of mourning.

These irreconcilable points of view have created a space of silence and misunderstanding between the two neighboring nations. With the exception of a few complicated initiatives relying on the dedication of librarians, a legalistic approach prevents these two major economic partners, allies in NATO and the EU, from moving on to a new stage of cooperation. In the summer of 2025, Krzysztof Ruchniewicz, the Polish official responsible for the coordination of German-Polish relations, was dismissed from his post because of a conference he was planning on issues of provenance. Within the various Polish parties, too, the topic of objects, including books, displaced by the war is explosive.9

Stuck in between worlds, waiting on the threshold, these bullet-riddled Bibles and Bach partitas remain in the shadow of a traumatic past. They belong to German culture, where they appear in catalogues as absence, mourning, loss, but they have not yet fully found their place in Poland. They are in limbo, which, according to the Collins dictionary, is « an imaginary place for people or things that are lost, forgotten or unwanted ». On both sides of the Oder River, they are thus bound up with impossible mourning.

In order to metaphorically « come out of the crypt », it is necessary to engage in a process of storytelling that acknowledges the wounds and losses inflicted by war. Germany, in particular, cannot claim an interest in books displaced during the war without recognizing, measuring and symbolically bowing to the extent of the destruction suffered by Poland. Only then can we move on to a more fruitful stage of mourning, and find a new way of looking at these objects as part of a collective European heritage that dates to well before 1939 and continues after 1945. Books are mobile, and their movement through time and space tells a story. Eighty years after the end of the war, « lost » books could be rediscovered and open up new horizons for cooperation between the two neighbors. Beyond sterile discussions about ownership, books, which cross borders and survive wars, are a powerful metaphor of resilience.

You’re reading this essay for free. With a membership, you can read the full magazine, and you get access to our fabulous Library.

Here’s our offer: 3 months unlimited digital access + 1 print edition for € 38,00 € 19,00

You’ll get Issue Eleven in print as your first magazine, right to your mailbox.

- Jakub Gortat, « ’Berlinka’. Ein besonderer deutsch-polnischer Erinnerungsort », Convivium: Germanistisches Jahrbuch Polen, no. 5 (2017), pp. 105-128 ↩︎

- See P.J.P. Whitehead, « The Lost Berlin Manuscripts », Notes, 33:1 (September 1976), pp. 7-15. ↩︎

- Izabela Mrzygłód, « Cisza archiwum, głos widma », Spectral Recycling [blog of the project on Resettlement Cultures in Poland, Czechia and Slovakia], 11 October 2024. ↩︎

- Jacek Kordel, « Der Büchermord: Die Zerstörung der Bibliotheken in der polnischen Hauptstadt während und nach der Niederschlagung des Aufstands (August 1944 bis Januar 1945) », Bücher und ihre Wege. Bibliomigration zwischen Deutschland und Polen seit 1939, edited by Vanessa de Senarclens (Brill, 2024). ↩︎

- See Andrzej Mężyński, Kommando Paulsen: Październik — grudzień 1939 r. (Warsaw DiG, 1994). It was translated into German as Kommando Paulsen: organisierter Kunstraub in Polen (Dittrich-Verlag, 2000). ↩︎

- Quoted in Kordel, « Der Büchermord », p.36. ↩︎

- Nawojka Cieślińska-Lobkowicz, « Sammeln, um zu zerstören: Die Vernichtung der deutschen und polnischen jüdischen wissenschaftlichen Bibliotheken », in Bücher und ihre Wege. ↩︎

- Patricia Kennedy Grimsted, Trophies of War and Empire: The Archival Heritage of Ukraine, World War II, and the International Politics of Restitution (Harvard Ukrainian Research Institute, 2001). ↩︎

- See, for instance, Stephan Stach, « Welche Geschichtspolitik darf’s denn sein, Herr Nachbarn », Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, 1 September 2025. ↩︎