Your Spanish, my Spanish, our Spanish

Sometimes it feels as if the tacos have been rubbed out of my tongue. For four years, I’ve been speaking a language that doesn’t belong to me, one that exists only through synonyms that are foreign to me. I’ve been living in the US for four years. The problem is not English — though I sometimes mistake a conjugation — but my own native language. My Spanish has not worsened, but it definitely has changed. My mexicanisms appear with lesser and lesser frequency in my daily speech. When I’m teaching Spanish and my undergrad students ask me the word for short, I have to fight my own instinct. I no longer say chaparro but pequeño. No longer cuate but amigo. No longer my Spanish but Spanish 101.

For a while I thought that this neutral Spanish (neutral for whom?) was limited to my classroom. That it was just a pedagogy tool so my undergrads could communicate with any Spanish-speaking person, as if the mark of a good teacher was her disappearance. However, on 3 December 2023 I realized that the erasure had started affecting me. That day, at around 8pm, I texted my mom: « how is this called? ». Attached was the image of the kitchen basin. Fregadero, she answered. I felt as if I was learning Mexican from my mom as I had done when I was a baby. Or perhaps I was un-learning Colombian because I had been listening to my boyfriend and his friends call that kitchen basin a lavaplatos during dinner. My boyfriend had colombianized my Mexican. But my friends had also argentinized it, chileanized it, venezuelized it, ecuadorized it. My Spanish is the kind that libertador Simón Bolívar dreamt for his Gran Colombia: Latin America united. My tongue is Simón Bolívar’s wet dream.

The irony of this essay existing in English does not escape me: an essay about translation, written in one language, translated into another. A translation whose edits in English I will have to translate back to the Spanish original. An essay that is necessarily two: a box within a box. It feels like trying to fit all the different shapes into the same round hole of a baby’s first shape-sorting toy. The words on the page are missing the rolling of the r, the short and intense vowels, the nuances of the accent that reveal my Mexican origin no matter how hard I try to fit into a Colombian parche. But still I keep trying to write, because if this essay in Spanish showcases the relation between supposed Spanish neutrality and the hegemony of the European Spanish dialect, the essay in English showcases what is lost in translation. It has to be written in English to show that it cannot be written in English.

You’re reading this essay for free. With a membership, you can read the full magazine, and you get access to our fabulous Library.

Here’s our offer: 3 months unlimited digital access + 1 print edition for € 38,00 € 19,00

You’ll get Issue Eleven in print as your first magazine, right to your mailbox.

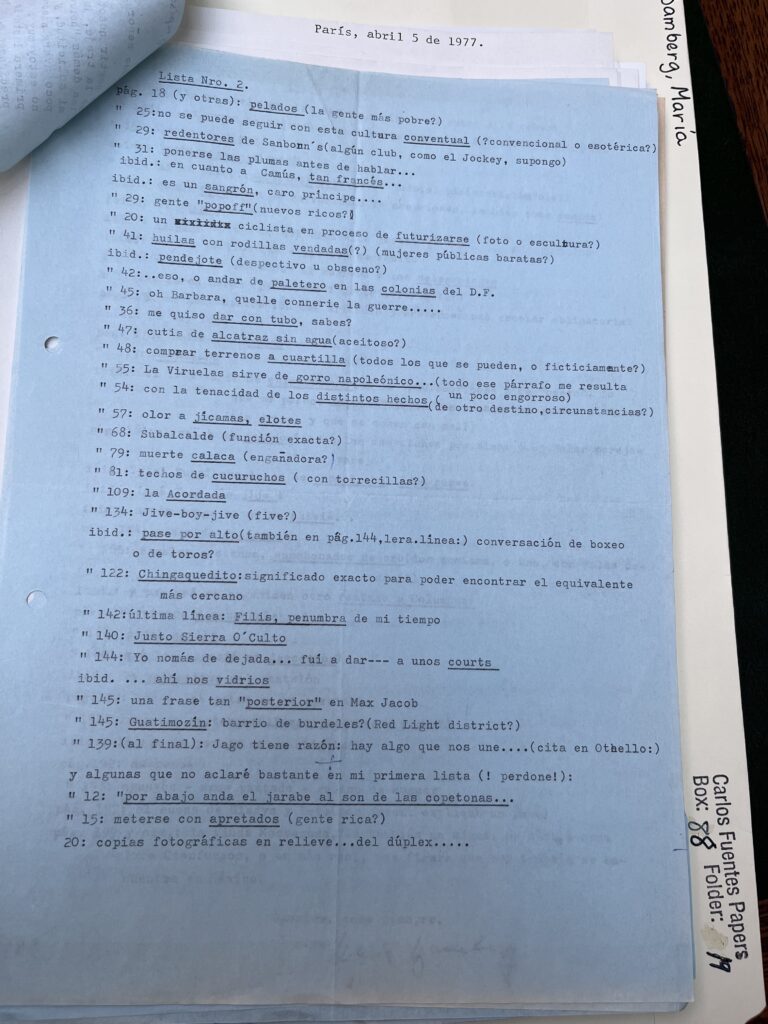

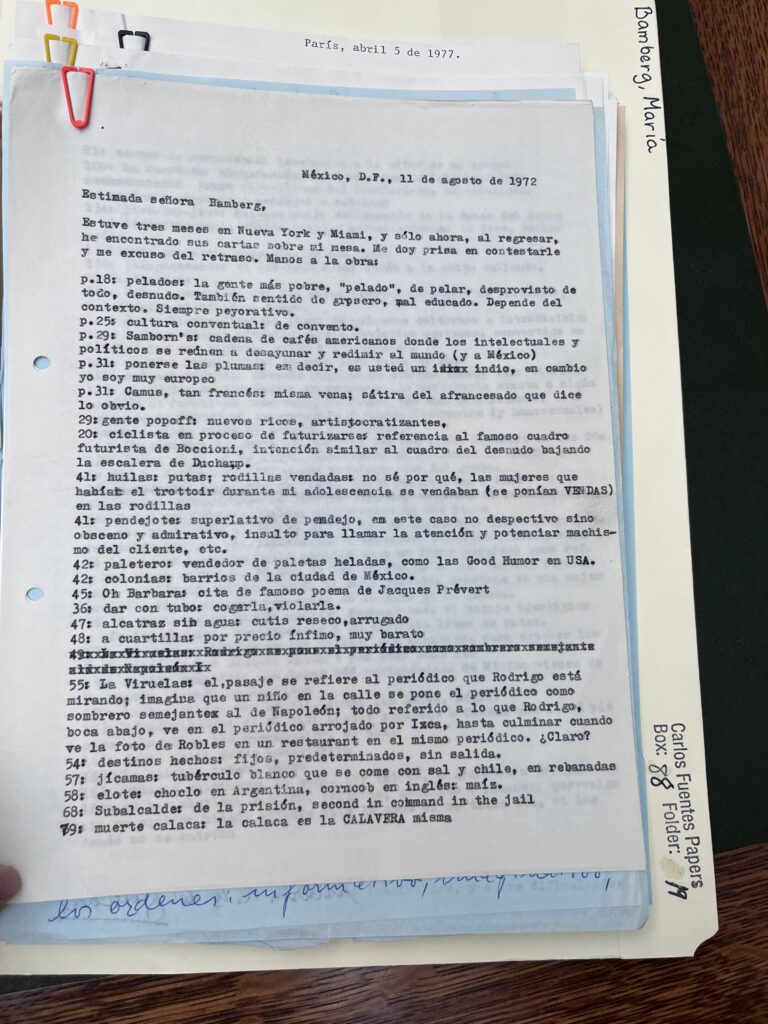

Just as my mom had to re-teach me my own Spanish, the writer Carlos Fuentes (1928-2012), Mexican representative of the Latin American Boom, had to teach his language to María Bamberg, his German translator. Both of them spoke Spanish, yes, but not the same language. Bamberg’s Spanish was of Argentinian origin, and therefore deaf to the Mexican regionalisms of Fuentes’ most famous novel, La región más transparente (1958), or Where the Air is Clear. Due to the linguistic difference, on 20 April 1972, Bamberg wrote to Fuentes with a first list of requirements in the form of clarifications. This led to a series of letters that inaugurated, almost by chance, a his-Spanish-to-her-Spanish dictionary. Among the words that compose this list are: daiquirí, trastabillado, afrenta, yanqui, popote, chamaco, garnacha, joto, andar abusado and mariachi. At least « mariachi » I hope, dear reader, you understand. (A note from my [originally Dutch] editor here mentioned that for the more adventurous drinkers among the readers, daiquirí might be familiar too.) This collection of words revealed that Bamberg did not understand the Mexican in one of the most Mexican novels in history, making her completely dependent on an air-mail exchange. According to the publisher that commissioned the work, Deutsche Verlagsanstalt Stuttgart, the translation had to be done by the end of July, which gave her only three months to translate herself twice: from Spanish, to Spanish, to German.

Fuentes shared his admiration / surprise / anguish regarding Bamberg’s complicated mission and looming deadline with her in his answer from 17 May 1972. He wrote: « it seems to me crazy to try to translate Where the Air is Clear in only four months, especially if, as is clearly your case, you don’t know the particulars of the Spanish spoken in Mexico. »1 However, Fuentes offered his help. In the first list he mailed her, a popote is defined as « a tube used for sucking liquid », a garnacha as a Mexican dish consisting of a tortilla covered with onion and cheese (there is, of course, the joke that every Mexican dish consists of tortilla, onion and cheese — like the taco, quesadilla, tostada, gordita, tlacoyo, flauta…), joto is defined as « fag and pedophile », and mariachis are defined as popular Mexican orchestras (a word that comes from French, as they mainly performed at marriages, or in French, mariages).

This rhythmical list had a later iteration that included words like chichi, jijo, chivié, papel, manila, descuachalangados, ahí nos vidrios, and chingaquedito. (Roughly translated to boobies, son-of-a-bitch, shame, paper, unkempt, see you later alligator, and pestering). Bamberg sent the last list of definitions on the 30th of May. Even if Fuentes had answered immediately, that would only have given her two months to finish tweaking her translation in time for the publisher’s deadline. Contrary to her earlier letter, which contained an air of haste, this letter reads as a thoughtful defense of her translating skills. In it she says:

I was a little embarrassed after sending the first list because you must have thought that I was not ready to take on a novel of that magnitude. I confess I wrote that letter somewhat hastily due to the four months I had for translating, which you rightly reprove. […] I would like to remind you, very humbly, that while a good translator needs to know, naturally, the language she is translating from she must dominate the language she is translating to, in this case, German.

The confidence that was lacking in Bamberg’s previous letters no doubt improved Fuentes’ opinion of her work. The result of the Fuentes-Bamberg correspondence wasn’t just the published translation of La región más transparente — Landschaft in klarem Licht — but a flourishing friendship between writer and translator. Bamberg would continue to translate Fuentes’ novels into German and their epistolary exchange continued as well, not in Mexican or Argentinian, but in a neutral mixture of both.

his translator, Maria Bamberg, who needed to translate Fuentes’

Mexican into her own Argentinian, before translating to German.

(Photos by Nora Muñiz)

The Spanish-Spanish dictionary that sprouts from the Fuentes-Bamberg correspondence iscdirectly related to German. But there is alsocanother version of that dictionary. Castillacis a historical region in the center of Spain (encompassing Madrid, Burgos and Valladolid) that took over the rest of the peninsula, imposing a religion and a language. This is why another name for the language spoken in Spain is Castilian – the one I teach in my 101 class, the one that believes in its own fictional neutrality. This Castilian has an accent too strong for my ears and a vocabulary too « refined » for my tastes. To me, it’s an imposition which makes itself most visible when I’m reading books, as the words that are not fully my own stand out to me on the page. (My boyfriend said Mexicans can’t really complain about this imposition because in every film that is dubbed in Latin America the characters speak with Mexican accents. I guess that’s fair. Chale.)

Most translated texts are translated into Castilian, because it’s considered « neutral », yes, and because Spain dominates the Spanish language publishing industry. For years, the Spanish speakers outside of Castilla – who speak Spanish but not Castilian — have read translations of classical texts via the most widespread publisher, named Cátedra. Even if published recently, Castilian translations tend to conjure an ancient imagery, just as some of our grandparents still use Castilian phrases learned from their own ancestors. The books are not only expensive but they work exactly as the name suggests: cátedra means lecture. The translations published by Cátedra continually impose Castilian as the only acceptable Spanish in which to read about Juliet’s or Madame Bovary’s untimely deaths.

In the Harry Potter series, Hermione says « color » in the Scholastic version published in America, and not « colour » as she does in the British Bloomsbury edition. The Dudleys go to the cinema in the UK and the movies in the US. Ron gets a jumper in The Philosopher’s Stone and a sweater in The Sorcerer’s Stone. A café da manhã does not need coffee in Brazil and a pequeño almoço in Portugal is not necessarily small. Both of them mean breakfast, but in Brazil a breakfast is called « coffee in the morning » and in Portugal « little lunch ». You could say that the argument of one dialect imposed as the neutral variant can be translated into any fractured language. You could be right, it’s normal to have a haupt to which the dialect is subordinated. But Castilian as the imposed dialect has a colonialist stench — the history of the Spanish empire plays a part in the imposition.

In his book Ideologies of Hispanism, Joan Ramon Resina, a professor of Iberian and Latin American cultures, states that the idea of hispanism is that of a uniform hispanic world represented through a monolingual territory, even after (or particularly after) the fall of the Spanish empire. If we think of the nineteenth century as the century of independences, it has not been the same in practice. The haste with which Latin American countries wanted to declare their independence from Spain forced them to use the Spanish language to underscore their political distance — as it was the most widespread common language (widespread through violent colonization practices). The need of these newly independent states to create their own patriotic symbols in order to unite the people — things like a national anthem and the first independent literary works — created a contradiction that Latin America cannot escape: every Latin American country that declared its independence from Spain did so in Spanish. This allowed people to relate to each other while at the same time binding them forever to the empire they rejected. The notion of hispanism, which has been celebrated by the Spanish crown for years, revolves around this inescapable relation. It’s not a coincidence that among the many proposed names for Spain’s national holiday of 12 October — which commemorates, among other things, Columbus’ « discovery » of America in 1492 — the option « Language Day » was particularly popular. 12 October is also officially known as « Day of the Race » which unites Spanish speakers in a blood-based hispanism.

You’re reading this essay for free. With a membership, you can read the full magazine, and you get access to our fabulous Library.

Here’s our offer: 3 months unlimited digital access + 1 print edition for € 38,00 € 19,00

You’ll get Issue Eleven in print as your first magazine, right to your mailbox.

On 24 November 1870, fifty years after losing their last American colony (Uruguay, in case you were wondering), Spain allowed its Real Academia Española — the royal language institution founded in 1713 — to establish local language academies within Latin America in order to promote relationships between the different republics, all siblings through language. The Real Academia Española works as a designator (and imposer) of linguistic rules. As the Real Academia Española placed local franchises like monopoly houses throughout the American continent, it also imposed its Castilian rules, denying the incorporation of local slang into the dictionary and thus limiting language understanding in Latin America. Words used in day-to-day life don’t necessarily appear in the dictionary.

Hispanism, then, promises a closeness that is fake and forced. It links together every Spanish speaker, even when we don’t want to be linked together. It does not appear as European citizenship. It does not take the form of economic reparations. Ah, but when we read a book published in Spanish, behind every vosotros and next to every a por ellos, our Castilian brothers invite us to the language party.

The Spanish-language literary publishing market consists of two big publishing houses — Penguin Random House Español and Grupo Planeta — which have been buying up smaller independent publishers and turning them into their imprints. This leads to a bland homogeneity: just as the covers have the same color schemes, the books start attaining a similar tone — one completely deaf to localisms. Localisms, in fact, are done away with in the process of editorial correction. And the Real Academia Española defines what should be corrected into what.

This brings to mind the Colombian writer Evelio Rosero Diago, and the frustration that exudes from his correspondence with his Barcelona-based editor prior to the publication of his novel Juliana los mira (1987). While Rosero had published before in his own country, this would be his first book in the Spanish market (and publishing in Spain usually means publishing everywhere in the Spanish-speaking world, as only publishers based in Spain have the requisite international infrastructure). Throughout his letters with his editor, Rosero is forced to defend his writing — which often goes against the Real Academia Española’s recommendations — with technical linguistic terms, as if only linguistics would give him authority over his words. In one letter, he says: « It’s not about spontaneity or a last minute invention. This is how it’s spoken in several regions of Colombia, Ecuador and Mexico, countries in which I have lived and books that I have read ». Which is as if he were saying: my Spanish is real. As if he were asking: don’t translate me to your Spanish. His editor, Manuel G. Palacio Alonso, offered a solution to which Rosero took personal offense: adding a short dictionary as a colophon.2 I took out the book from the library in order to find out who won the language war. Technically the Colombian did, as the book appeared without a colophon. But the book had to change publishers in 2015 and has not been reprinted since. The win, then, is not as sweet.

Throughout the years, Latin American authors have learned how to play with the rules of hispanism and laugh in the face of the RAE’s orthographic correction. Cristina Peri Rossi, an Argentinian poet who worked at Lumen publisher in Barcelona in the seventies, wrote to her boss to tell her that « according to the latest rules of the Royal Academy of Spanish (oh lord), whisky, a drink of Scottish origin distilled by the black women of the [US] South during the Civil War, should be written as güisqui ».3 Latin American authors have learned they can write their Spanish as long as they disguise it with an explanation. In the novel Aquí sólo regalan perejil (2019) by the Colombian writer Luis Luna Maldonado, the narrator says:

the one that is going to drop the cháchara is me… what is cháchara, hmmm, let’s see. It’s when one talks shit, drops random words and the listener doesn’t give a damn. Or the « abundance of useless words » according to the know-it-all dictionary that is just a nerd and knows nothing of the real world.

Maldonado, or his narrator, defines cháchara not only with his own words, but also with those of the institution behind that nerdy dictionary: the Real Academia Española. In No voy a pedirle a nadie que me crea (2016), the hilarious novel by Mexican writer Juan Pablo Villalobos, a Mexican PhD student moves to Barcelona to study — but his whole degree is just a cover for a forced career as a drug dealer. Linguistic humor is the topic of his dissertation, but it’s also found in the distance between Mexican Spanish and Castilian. He goes from mexicanisms to castilianisms just to underscore the meaning of what he’s saying. I’ll try and fail to translate one example into English: « if you are a fucking secretary who is reading this letter, you know what, fuck you. Or, as the [Castilian] Spanish movies say, just so you get it: ‘piss off’. » From both Luna Maldonado and Villalobos I gather that the writers translate themselves more for the editor than for the reader.

For years, the different types of Spanish have tried to find a common ground within the market. Not my Spanish or your Spanish but our Spanish. The true language party. BYOB. This is the party to which Cuban writer Guillermo Cabrera Infante invites us with Dublineses (1972), his translation of James Joyce’s short story collection from 1914. Anyone familiar with Joyce’s prose understands the contradiction present in the text between Irish nationalism and the predominant English language. Guillermo Cabrera Infante takes that contradiction and runs with it — Dublineses is marked by a contaminated Spanish, filled with castilianisms, cubanisms, catalanisms. The Castilian « corrections » imposed on the text by a Spanish typist as she copied it, spurred the translator to write a warning in red ink directed to editors, correctors and printers of the book:

The words you find here have been written with the desire to make this book not only the most faithful to the author but also to the translator, who, believe me, has worked extremely hard to make this readable for any possible reader in the three continents that read this so-called language.4

The Spanish is global, the Castilian is the one that is local.

During my most recent Christmas vacation in Barcelona, walking among the caganers, I entered the bookstore Finestres. There, I bought — without any consideration for my weeping wallet — two versions of Dubliners translated to Spanish. The first one was Guillermo Cabrera Infante’s translation, published by Penguin Random House. The second translation was by the Spanish author Eduardo Chamorro, published by Alianza in 1993. As I was reading one book on top of the other, I was surprised at how deeply Castilian Chamarro’s translation was, while Cabrera Infante’s felt fully Spanish — with all its richly textured nuances. Reading the words of the old man of the first story, I realized that Cabrera Infante made him sound more Castilian to underscore his age and social class. In Chamorro’s work, every character seemed Castilian and, despite living in Ireland, you could picture them eating paella. Cabrera Infante’s characters could eat paella but also arepas, caviar, tacos and even ice cream. Juxtaposing both books, I could have believed Cabrera Infante was a Castilian author, but I could never take Chamorro for a Cuban. The syntactic fusion of the language turned Guillermo Cabrera Infante’s translation into more Spanish than the Castilian version, without losing the Latin American flavor.

Recently, I found an editing mistake which gave me the hope that escape from predominant editorial corrections is possible, that the trap of the colonization of language isn’t eternal. In 2020, the independent Los Angeles publishing house Semiotext(e) published the Australian writer McKenzie Wark’s Reverse Cowgirl, a sexual biography, a work of trans literature that plays with the borders of language. In 2022, an Argentinian Spanish translation of Reverse Cowgirl was published by Caja Negra, which — despite being an independent publisher from Argentina — has a strong presence in Spain. So much so, that it prints all its books for the non-Argentinian market in Spain.

The book (both the original English and the Argentinian translation) is about fucking, about penises, about sex. Characters walk around the street and fuck — they fuck a lot. But, while in Argentina « to fuck » is coger, in Spain, coger means taking something. In Spain, one coge the bus. In Latin America, you would have to see a psychologist. The word used for fucking in Spain is follar. In Spain, follar; in Latin America, coger. You can imagine my surprise when I found Reverse Cowgirl (translated as Vaquera Invertida) in Spain — after having read the Argentinian version — and noticed its characters were follando instead of cogiendo. Had the book been translated into Castilian as well? I looked over at the cover and it was the same as in Argentina, with the same press and even the same translator. At first glance, the only two differences I noticed were the quality of the paper and the translation of the word for fucking. After a bit more reading, I realized that the printer from Madrid must have decided to castilianize this particular Argentinian translation. They must have changed all the coger to follar and all the rutas (roads) to carreteras (highways). However, during the process, someone made a mistake when using CTRL+F and forgot to ensure that only the self-standing word would be replaced. Instead, compound words were taken along in the great replacement. This leads to some beautiful new words, like esfollar, which inserts follar into escoger (escoger means to choose). Or disfcarreteraba, which inserts carretera into disfrutaba (disfrutar means to enjoy). Or fcarreteras which inserts carretera into frutas (frutas means fruits). Imagine trying to enjoy a book when you’re suddenly confronted with a « fruitway » instead of a « highway ».

This example of clumsy hispanistic correction could be our solution: a new Spanish. A mutant Spanish. One we could all enjoy, even if the autocorrect does not agree with us. One that would make Simón Bolívar proud.

You’re reading this essay for free. With a membership, you can read the full magazine, and you get access to our fabulous Library.

Here’s our offer: 3 months unlimited digital access + 1 print edition for € 38,00 € 19,00

You’ll get Issue Eleven in print as your first magazine, right to your mailbox.

- Carlos Fuentes Papers, Firestone Library, Princeton University, Box 88, Folder 19. (This and all other translations in this essay are my own.) ↩︎

- He answers: « I don’t think it’s in my best interest to publish my first book in Spain with a colophon, with justifications that I should not be giving. » Carmen Balcells Papers, Archivo General de la Administración in Alcalá, Madrid, box 13/1133. ↩︎

- From the archives of Lumen’s director, Esther Tusquets, housed at Biblioteca de Cataluña, Barcelona. ↩︎

- Another find from the Esther Tusquets Papers. ↩︎