Mission: Impossible – Dead Reckoning (Part One)

Christopher McQuarrie, dir.

2023

Mission: Impossible and Eurocentric stunts, from Hollywood to Hong Kong. What does an action movie want to be?

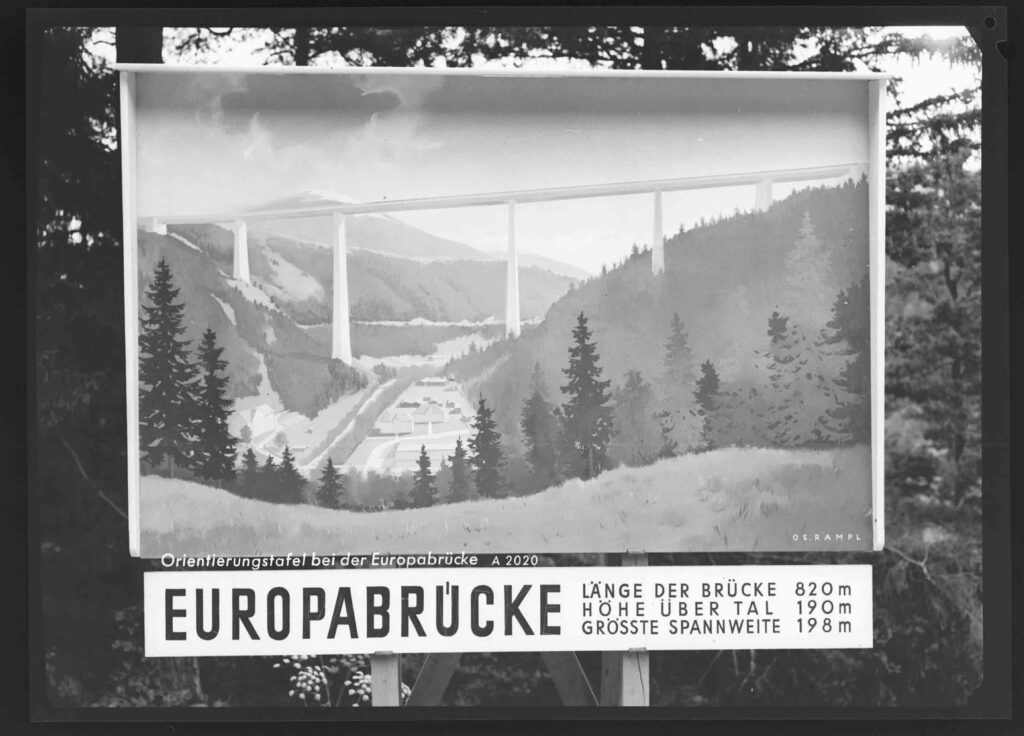

Orientierungstafel bei der Europabrücke, near Innsbruck (1961), Vorarlberg State Library, Austria (CC BY).

The American super-agent and the British super-agent are in love. For a moment, they’re together in Venice, and the British super-agent admits, to her own surprise (and ours), that she’s never been to Venice before. Neither has he, believe it or not. Theirs is a star-crossed love, for they cannot escape their calling. The movie’s Venice is definitely the real Venice, with a fight in a Venetian corridor too narrow to swing a sword in, and a death on an old bridge.

I saw Mission: Impossible — Dead Reckoning (Part One) in Amsterdam. Early in the film, when the mission is delivered, the mission that Tom Cruise / Ethan Hunt will inevitably choose to accept (it takes the form of an analog tape deck that self-destructs after five seconds), the location-title reveals that he’s in Amsterdam, which made the audience around me titter: hey that’s where we are, too! But the film never shows us Amsterdam, only a nondescript shadowy interior, so now I just assume that every screening of the movie names whatever city the screening is in.

Before pondering the locations of action cinema (and thus the vectors of our own nostalgias and aspirations), let us briefly rehearse the mystique of Tom Cruise’s action-hero Method-acting, and its storied relationship to cinema as art and industry.

The plot of Dead Reckoning (Part One) revolves around a fancy cruciform key that looks both antique and futuristic. It has two parts; when they’re locked fancily together, four jewel-like lights on the key’s bow glow, giving the key a Benjaminian aura of Unreproduzierbarkeit. Our protagonists have one part of the key; they need the other part. The key, we’re told, unlocks the as-yet-unrevealed device that will allow humanity to control or destroy an ominous artificial intelligence.

The AI — self-aware, rogue, malevolent — is Dead Reckoning (Part One)’s disembodied, inscrutably brilliant villain. Everyone calls it « The Entity », and it can infiltrate all digital systems, from a submarine’s sonar system, to diplomatic communiqués, to mainstream news outlets, to your basketball-related group chats, to our heroes’ own communication devices, imitating the very voices of our dearest friends and « field agents ». The Entity can rewrite the truth in real time. No wonder every power on the globe fears it, and wants it. Unleashed upon a vulnerable world, it forces governmental intelligence agencies back to analog technologies — paper, typewriters, vinyl, maybe wax cylinder? — which suggested to me that the Entity was in fact Wes Anderson. (Ironically, the giant CIA room with the rows of endless desks and endless typists that the Entity has necessitated felt more computer-generated than the mountain-disguised ramp that Cruise will ride a motorcycle off of.)

Ideas are anathema to an action movie, but action movies that manage to be clever allegories of themselves? I’m in. The Mission: Impossible franchise has become so saturatedly self-referential — so thoroughly about itself and about its own means of production — that even the grumpiest Frankfurt School theorist would have to commend it. They are movies about their own commodified auras. In the last one, Mission: Impossible — Fallout (2018), the villain was « The Syndicate », a shadowy terrorist organization bent on dismantling the old world and ushering in the new; but the real villain was Netflix, or streaming in general, and the streaming economy’s dismantling of true cinema. It opened with a public service announcement from Cruise, as himself, personally thanking everyone for coming to see his humble human blockbuster. « We made it for you. »

Dead Reckoning (Part One) arrives with even greater stakes and an even thinner allegory, for the real villain is computer-generated imagery (CGI). Cinema’s fate rests on Cruise’s devotion to his own stunts, to the stunts’ authenticity and excess. Practical special effects (a good oxymoron) take on a religious grandeur. Writing about Fallout in n+1, A.S. Hamrah described Cruise as « a live-action testament to his own ability to take punishment, a kind of human sacrifice. He is undiminished by both time and all the semi-comedy around him, which is the story of his career and his life. » Much is made of Cruise’s Scientology, but his real prophet isn’t the L. Ron Hubbard of Dianetics but the Harold Lloyd of Safety Last! (1923), in which the great silent action-comedian hung from a skyscraper’s ticking clock, twelve stories up, fending off pigeons, all because there was no other way. In Mission: Impossible — Ghost Protocol (2011), Cruise’s most explicit valentine to Lloyd, he scales the Burj Kalifa in Dubai, and then sprints sidewise around it as a sandstorm looms.

Humanism can reach perverse heights. In the perilous present, Cruise must outperform the machine of CGI, like a white John Henry, the « steel-driving man » who pitted his humble human sledgehammer against the steam-powered rock-driller and died in his victory. If Cruise dies in the process, his death will be messianic, or at least folkloric.

At its best, Dead Reckoning (Part One) is a masterpiece of contextualist action film-making. The franchise, rooted in Cold War intrigue, has always been nostalgically Eurocentric, although the earlier entries’ most eye-catching action scenes have been set less often in sites of the European past than in cities of the global future. Mission: Impossible III (2006) culminates with Cruise’s sprint through Shanghai. The Dubai sequence in Ghost Protocol is way more memorable than the final battle in a futuristic parking garage (between Cruise and the guy-with-the-briefcase-containing-a-bomb-detonator); I don’t even remember what continent they were on. Mission: Impossible — Rogue Nation (2015) was the most « British » entry in the franchise, appearing one year before the Brexit referendum (coincidence?), and though its big water-based action scene (for which Cruise held his breath for six minutes or whatever) is set in a Moroccan power plant, the plot resolves, tweedily, in Oxford.

Mission: Impossible — Fallout (2018) spins its motorcycles around the Arc de Triomphe for awhile, but ultimately lands in Asia, specifically the Siachen Glacier in the eastern Himalayas. The climax is on a Himalayan cliff, where Tom Cruise’s Ethan Hunt and Henry Cavill’s mustache will fight over the little doohickey that will defuse the nuclear bombs that are at that moment counting down to the obliteration of « everyone in China, India, and Pakistan — a third of the world’s population and », as Hamrah noted in n+1, « a substantial market for films like this. »

All of which is to say that the newest one marks a particularly « European » return. Sure, Dead Reckoning (Part One) jets us briefly to the Middle East, where the desert action can evoke both the cowboy shootouts of Sergio Leone’s bleak Western frontiers and the horse-and-turban theatrics of Lawrence of Arabia. And then we see people with fancy augmented-reality glasses chasing each other through Abu Dhabi International Airport (filmed, in reality, at Birmingham’s airport). But after that, the adventures stick to Italy and Mitteleuropa.

« We let the city tell us the kind of chase it was going to be », the director, Christopher McQuarrie, says in a behind-the-scenes video about the making of the bravura car chase in Rome. (The chase has Tom Cruise and Hayley Atwell’s mysterious thief character careening around Rome, handcuffed together in a tiny yellow Fiat.) McQuarrie’s fine ear for a city’s expressive whisper reminds me of the oracular advice that the architect Louis Kahn gave to students: What does a brick want to be?

Then again, whole landscapes will masquerade as other landscapes. The Trollveggen, in the Norwegian Romsdalen Valley, poses as a Swiss Alp so that Cruise can ride a motorcycle off of it, there being no other way for him to catch the runaway train that’s bound for Innsbruck. Sadly we never get to Innsbruck, for the train in question will eventually plunge from a bombed bridge, in a reverential, meta-cinematic homage to the train chase in Buster Keaton’s silent classic, The General (1926). Keaton’s story took place in Georgia, but the actual train was wrecked in Oregon; Dead Reckoning’s Austrian trainwreck was filmed in the English village of Stoney Middleton, after an old bridge in the Polish village of Pilchowice proved impossible, alas, to destroy.

The debacle of the Polish bridge is a minor but revealing misadventure unto itself. Way back in summer 2020, when they started making the movie, word got around that Mission: Impossible’s makers wanted to blow up an 111-year-old protected monument — how dare they! — which forced McQuarrie to issue a clarification, showing some of action-cinema’s gears in the process. Since Mission: Impossible is « a franchise that does as much as humanly possible without the use of digital effects », he wrote in his statement, and since yes, they did need to hurl a train off a busted bridge, « a broad search was initiated in the unlikely event that any country anywhere in the world might have a bridge that needed getting rid of. » A nibble from « some lovely people from Poland », enthusiastic for the tourism and film-production revenue that would surely follow, hipped McQuarrie & co. to a decrepit, unused bridge that would have been perfect. Clearing his franchise’s name required McQuarrie to peel back the layers of local history:

The bridge was not built entirely in 1906 as has been reported. That bridge was partially destroyed by the retreating Germans during the Second World War before being rebuilt (the current bridge is, in fact, one of two very similar ones in the area, neither of which is a protected monument). Bottom line: to open up the area to tourism, the bridge needed to go.

So: kill one bridge with two economic imperatives, and everybody wins. It would spur the rail system’s renovation and thus facilitate the tourism that would flow toward Pilchowice at least in part because Mission: Impossible had blown up a bridge there.

This virtuous cycle was sabotaged by one disgruntled person, who « claimed they were owed a job on the production for which we felt they were not adequately qualified », and whom McQuarrie does not name. Let us call this manifestation of disgruntlement « The Entity ». The Entity cunningly rewrote the reality of the bridge in real time: it was The Entity that invented a tradition for this meaningless bridge, and then tried to have it landmarked as historic. And then, McQuarrie laments, The Entity « reached out to us to gloat about it. » The Entity « manipulated the emotional response of the people in a move that has now compromised our ambitions to bring our production to Poland. » What does a bridge want to be? Its destruction would have been its apotheosis.

I will conclude this review with what will seem like a non sequitur. (What does a non sequitur want to be?) Back in 2019, on a plane, I watched a Chinese action movie called Europe Raiders, and the disorientation it produced was about as vivid as the escapist nostalgia stirred by Mission: Impossible.

The CIA hires the legendary bounty hunter Lin Zaifeng, played by the great Tony Leung (another actor — Tom Cruise’s age, incidentally — undiminished by time), to track down the movie’s MacGuffin: a data-weapon called « The Hand of God », which is in Italy, so Europe Raiders is set pretty much entirely in Italy. The CIA, you see, had dragooned the most brilliant hacker in the world (a gentle genius named Mercury, played by the pop crooner George Lam) into creating the Hand of God years before. Like Dead Reckoning’s cruciform key, the Hand of God has two parts, and they’ve been stolen by Mercury’s now-grown-up children, an evil-seeming daughter and a good-seeming son. The Italian chase is on. Prisons are escaped from, satellites are hacked into, a mafia-organization is allied with (and then double-crossed), glowing vats of nuclear waste are dangled over. A twist will reveal that Lin Zaifeng and the Mercury family are, in fact, on the same side, and that they’ve engineered every turn of the labyrinthine plot (even, somehow, the lavishly choreographed fights they have with each other?), all for the sake of tricking the CIA into re-installing what it thinks is an upgraded Hand of God, only to crash the CIA’s whole system.

Europe Raiders was filmed on location in Milan, at least in part. A lovely campo in a place called « Chinatown, Italy » gets undeservedly wrecked when Tony Leung and the Mercury brother defeat an entire army of CIA agents there (or mafia henchmen? or both? I can’t exactly recall). Leung beats up some guy while simultaneously catching a cup of espresso that’s been sent flying in the melee, nary a drop spilled. Their coolness dodges bullets. Europe Raiders is (I assume) the rare Hong Kong action movie in which speaking Klingon figures into the plot, but they make even Klingon seem cool, while the CIA is a bumbling organization of white men whose English sounds dubbed. The climactic fight, sadly, takes place in a mostly-CGI industrial complex, the kind of place that exists only for action movies to be set in. There never was a there there. It was forgettable, except that I haven’t forgotten it.

I cannot say what vectors of nostalgia and aspiration drove the making of Europe Raiders. To me, it felt like a Hong Kong action movie borrowing from a Mission: Impossible movie crossed with an Oceans 11 movie elevated into an extremely stylish Italian commercial for a newly-wealthy class of Chinese tourists. When I saw it, the European Review of Books did not yet exist, but Europe Raiders made me wish it did, if only to commission a writer more capable than I to survey the corpus of Chinese action movies set in Europe. Surely there are brilliant allegories to be decoded and savored.

Europe Raiders isn’t one of them, but it stuck the landing, at least. The movie ends with the former heads of the CIA working at a pizza restaurant. All together. Just making pizza. The pizza restaurant is not a CIA front; it’s a normal pizza restaurant, in Europe. I can imagine worse comeuppances.