On Israel-Palestine’s broken geography, Paul Klee’s angels (here below), and Walter Benjamin’s philosophy of history. Past catastrophe surges into the present.

Every image of the past that is not recognized by the present as one of its own concerns threatens to disappear irretrievably.

Fifth thesis on the Philosophy of History

I

A dark helicopter traverses a cloud-torn blue sky; another chopper comes into view, following the same flight path, propellers noisily threshing the air. The helicopters are military, carrying who knows what to who knows where, surveilling whatever they want to see. We pan down through gentle, gold-aqua light to a desolate coastline, low breakers spreading sine waves over a wide sweep of sand. In the background looms an unfinished skyscraper projecting floor-by-floor slats for future balconies. Then the picture jump-cuts to a metal fence blocking access to a jetty plastered with warning signs, followed by a shot of a fenced-off scrap of ocean. Two burly, bronzed men wearing wraparound black shades stumble over the sand, one talking on a cell-phone, the other sucking a smoke. The man on the phone, after a few seconds of banter, begins exclaiming in Hebrew: « What do you want from me? »

The two walk toward a half finished billboard advertising a « Mediterranean Building in the Marina », 4-5 bedroom apartments, along with penthouses. Whereupon the man with the cigarette turns away from the camera and brings his left hand to his trousers front — apparently preparing to urinate into the sand.

You’re reading this essay for free. With a membership, you can read the full magazine, and you get access to our fabulous Library.

Here’s our offer: 3 months unlimited digital access + 1 print edition for € 38,00 € 19,00

You’ll get Issue Eleven in print as your first magazine, right to your mailbox.

Before five minutes of the documentary Route 181 have elapsed, we’ve already gotten multiple hints of what it means to mark one’s territory as an expression of power. In a moment, we’ll learn that the scene is taking place near Gaza and that these men are contractors for a luxury coastal development rising in the midst of an outburst of violence between Jews and Palestinians. It’s remarkable that throughout Route 181, which was made 23 years ago by the Israeli filmmaker Eyal Sivan, together with the Palestinian filmmaker, Michel Khleifi, and which lasts almost four and a half hours, nearly every interaction feels both densely layered with history and hauntingly resonant with present-day headlines.

In the summer of 2002, when the Second Intifada was raging across Israel, the Occupied Territories, and the Gaza Strip, where targeted assassinations and frequent Israeli military raids were further degrading living conditions that had already cemented Gaza’s reputation as the world’s largest ghetto — even as suicide bombings by Hamas were being carried out against Jewish civilian and military targets, and even while settlers were rampaging against Palestinian civilians, fields and homes — Khleifi and Sivan set out to drive the length of the imaginary border between the make-believe versions of Palestine and Israel decreed by Resolution 181. This was the two-state plan adopted by the United Nations in 1947, which gave 56% of the land to the Jewish minority, and 43% to the Palestinian majority, while the remainder was to be preserved as an international zone. The film’s title turns a formal declaration into an itinerary — more precisely a series of disjunctive pathways, which shape the course of this unique road movie.

The boundary delineated by Resolution 181 that the UN presented as a solution instead incited the first Arab-Israeli war — a war which has yet to end, as captions projected over map fragments explain during the film’s opening credits. Later in the preamble, a red line begins snaking over the map, tracing this non-existent dividing-line between the two never-established iterations of the Jewish and Palestinian homelands, while a map of the whole land appears collaged over the eastern half of this mutilated country — a long aliform shape, narrowing at the top and base, which to my mind today conjures a single, scrawny wing from Paul Klee’s famous image, Angelus Novus, if that were torn from the body of the enigmatic, alarmed seraph, and planted in space between the sea and the desert.

I saw Route 181 for the first time in Germany in the summer of 2025, at a screening that happened to coincide with an exhibition at the Bode Museum titled « The Angel of History » featuring Klee’s picture together with handwritten pages from the Walter Benjamin 1940 essay that bestowed this name on Klee’s figure. Benjamin’s Theses on the Philosophy of History positioned the angel as a kind of archetypal martyr for the miscarriage of civilization’s presumptions. The two Berlin shows appeared inescapably constellated by unfolding events in that summer of catastrophe in Gaza and beyond.

As Sivan and Khleifi drive the unmarked borderline between nowhere and nothing, they shoot the often shattered landscape through their windows and stop to talk to people they chance upon: construction workers, food vendors, displaced or harassed Palestinian property owners, curators of small museums celebrating one or another Zionist victory, Palestinian archivists of the Occupation’s encroachment, wedding guests, shepherds, artists, Israel-ecstatic American Evangelicals, grieving Palestinian and Jewish parents. The conversations are juxtaposed with scenes of Jewish soldiers manning checkpoints and of Palestinians struggling to cross checkpoints, and of people on both sides of the separation wall then being erected trying simply to live — an endeavor that’s shown to be increasingly impossible for Palestinians. All these moments are interspliced with images of the road, blazing skies, deepening twilight, dust and darkness.

For the most part, Khleifi interviews the Palestinian subjects, while Sivan interviews the Jewish Israelis, which in practice means that Sivan does most of the talking since the camera finds more people from the latter group. He is not a neutral questioner. At times he speaks with barely suppressed, prosecutorial frustration, or a kind of incandescent compassion. Over and over Sivan asks his interlocutors whether they’re aware that the land they are on once belonged to Arabs who are now refugees in Gaza or elsewhere — whether they know that their living space is superimposed over or stands adjacent to the site of a destroyed or vacated Arab village, or whether they realize that this place was formerly known by a particular Arabic name. He relentlessly reminds people that their contemporary existence derives from the severance point of another line of history. Often those questioned in fact do know something of the past he alludes to. But their positions on the present-day significance of the place’s pre-1948 identity are staked out beforehand. Some version of « what happened happened and we all. have to move on now » is a regular, if not invariable Jewish response. This might seem surprising, given Zionism’s commitment to restoring a long-lost axis for Jewish existence in the land, but these respondents seem to indicate, « Now that our own reinstatement has been accomplished, the process of historical recovery stops here. » Thus, when Sivan inquires of one of the two Jewish contractors (a man who himself came from Kurdistan) whether he knows that the land they’re building on had belonged to Palestinians who were forced to flee to Gaza, the man scoffs. « Forget that… We were also here once. We had land in Kurdistan too. Can I get it back? They started a war, invaded and lost. End of story. How many times? One? Two? Three? Four times? »

He says that the Arabs are animals; if they weren’t, they’d still be living where the new development is now rising. On being reproached for that slur by one of the filmmakers, the man shrugs. « What do you want? We gave them everything. Before the ‘67 war, what was Gaza? Nothing. Peasants. We taught them to build, repair cars. Look now — roads, sewers, we did everything for them. But they just want to kill us. That’s it. Killing soldiers, fine. War — fighting for your land … I understand that. But killing kids on a bus? »

As for the Palestinians Khleifi interviews, their position is typically antithetical to that expressed by their Jewish counterparts — something along the lines of, « What happened is ongoing and will not be erased from us. »

There are also a few voices that disarrange the binary narratives. So, for example, when the camera addresses two young Bedouin workers who are surveying the future marina development, one declares that he plans to serve in the army because Israel is his country, and the military is fun, while the other hopes to leave their homeland to start a new life in America. Both acknowledge that the plight of the Palestinians is terrible, but they feel no attachment to Palestinian culture, with its domestic conservatism, and apportion blame also to other Arab countries that could have intervened but did nothing in the midst of their own political quagmires. Looking forward, the surveyors see only more fruitless struggle — a land burning forever at the intersection of irreconcilable narratives. To these youths, there’s nothing to do but get on with their own lives, which for one of them means identifying with the dominant (Jewish) population and for the other means getting the hell out of the region.

You’re reading this essay for free. With a membership, you can read the full magazine, and you get access to our fabulous Library.

Here’s our offer: 3 months unlimited digital access + 1 print edition for € 38,00 € 19,00

You’ll get Issue Eleven in print as your first magazine, right to your mailbox.

The repudiation of deadlocked nationalism is expressed piercingly at the end of Route 181 when the filmmakers interview a Jewish-Tunisian woman whose youngest child was killed in the last Lebanon war. He was the loveliest boy, she says. Twenty years old — a friend, a brother, a father, and that’s why she can’t abide Israel. « It’s a waste of time. A catastrophe… I’m a mother and this is not a game. The land is a beautiful country, blessed be God. It’s not like we lack anything here. But there’s no joie de vivre. No one enjoys life. » She describes what it’s like to hear of death after death, year after year. In Syria, in Lebanon, in Gaza, until one throws up one’s hands. « Everyone is human, » Khleifi says to her. « Every person is human! » she concurs. « Some say Arabs are bad. Some say Jews are bad. But we have to make peace. » « Do you think we can live together? » the filmmaker asks her. « Without doubt! Without doubt we can. As we did in Tunisia. » There and elsewhere Jews and Arabs were companionable neighbors, she recalls. « We’d drink a cup of tea together, a simple, peaceful life. Here, even if you have it all, you have nothing… »

The filmmakers drive off again into the waning day, barbed wire filling the windshield with labyrinthine curlicues enclosing an area fluttering with illegible ensigns — imagery recalling the opening when the camera leaves the Bedouins behind to go on the road, barreling through scrubby flatland, past a blue-and-white billboard featuring a Star of David beside the slogan, « We Wave the Flag, We Continue to Live the Dream. »

Insistence on the right to continuity, and of continuity threatened or denied, forms a central theme of Route 181. The clock of almost everyone we encounter over the course of this propulsive film appears set to a different time-period — a different step-by-step sequencing culminating, inevitably, in arrival or expulsion. A different fantasy of the future as clean new time, or a stage for the recurrence of some identity-defining calamity, or the stroboscopic timelessness of a continuous dream radiance — millions of misaligned timepieces orbiting a different rupture or promise, a different psychic capsule of what the past once held or has since clawed away from the present. There is simply not enough synchrony to the clocks throughout Israel-Palestine for history to move forward persuasively. This politically stultifying temporal dissonance appears etched in the bitter, amused, helpless, stunned, righteous, lacerated, angelic expressions on the countenances of these individuals dispersed by successive storms of fury and exaltation across this tiny, immeasurable country.

In the 23 years since Route 181 was shot, the situation is the same — only worse. The filmmakers’ conversations with the individuals they encounter, the familiar stories of violent Israeli assaults on Palestinians along with everyday cruelties that constantly impede normal existence, feel consubstantial with current realities, except that everything has become that much more lethal. But there is in fact one leitmotif that would be unlikely to recur if Khleifi and Sivan’s road trip were undertaken today: In 2002, surprising numbers of both Jewish and Palestinian interviewees either personally remember — or recall hearing of from parents or grandparents — of a time when the two populations co-existed not just peacefully but with some degree of mutual empathy. These individuals speak of the way things once were in tones alternating between wistfulness and a kind of apprehensive bewilderment. Even when the interviewees appear to understand how and why these relationships disintegrated, the knowledge remains unassimilable of just how much was lost.

Yet in this very disorientation we may detect a spark of vitality, a flicker of recalled commonality which seems to offer the clearest prospect of a tomorrow that’s something other than a recapitulation of today. Those who, like the woman from Tunisia, can summon memories of Arab-Jewish coexistence are often able to envision harmonious relations in the future as the resurfacing of an older, natural, geo-historical fundament rather than a total break with the past. To recognize that things did not always look the way they do now confers a sense of the present as porous and electrically veined with other configurations of people and territory. « The finding of an object is always a refinding, » Freud wrote of our capacity for love. This idea is correlative with a maxim from the Viennese satirist Karl Kraus, « Origin is the goal » — a precept Walter Benjamin used as the epigraph for one of his theses on history in which he described how « to Robespierre, ancient Rome was a past charged with the time of the now which he blasted out of the continuum of history » to undermine the official conceit of class-bound French society. One might cautiously ask then, could the moment of insistently remembered, at least essentially humane coexistence between Arabs and Jews be wrenched out of the past as a model for revolution aimed at peace?

But if one were to travel « Route 181 » today, would the names of former Arab villages still come to the memory of so many Jewish interviewees? And without even the shared remembrance of place names to build on, how can a new language be developed to bridge the abyss between the land’s peoples?

II

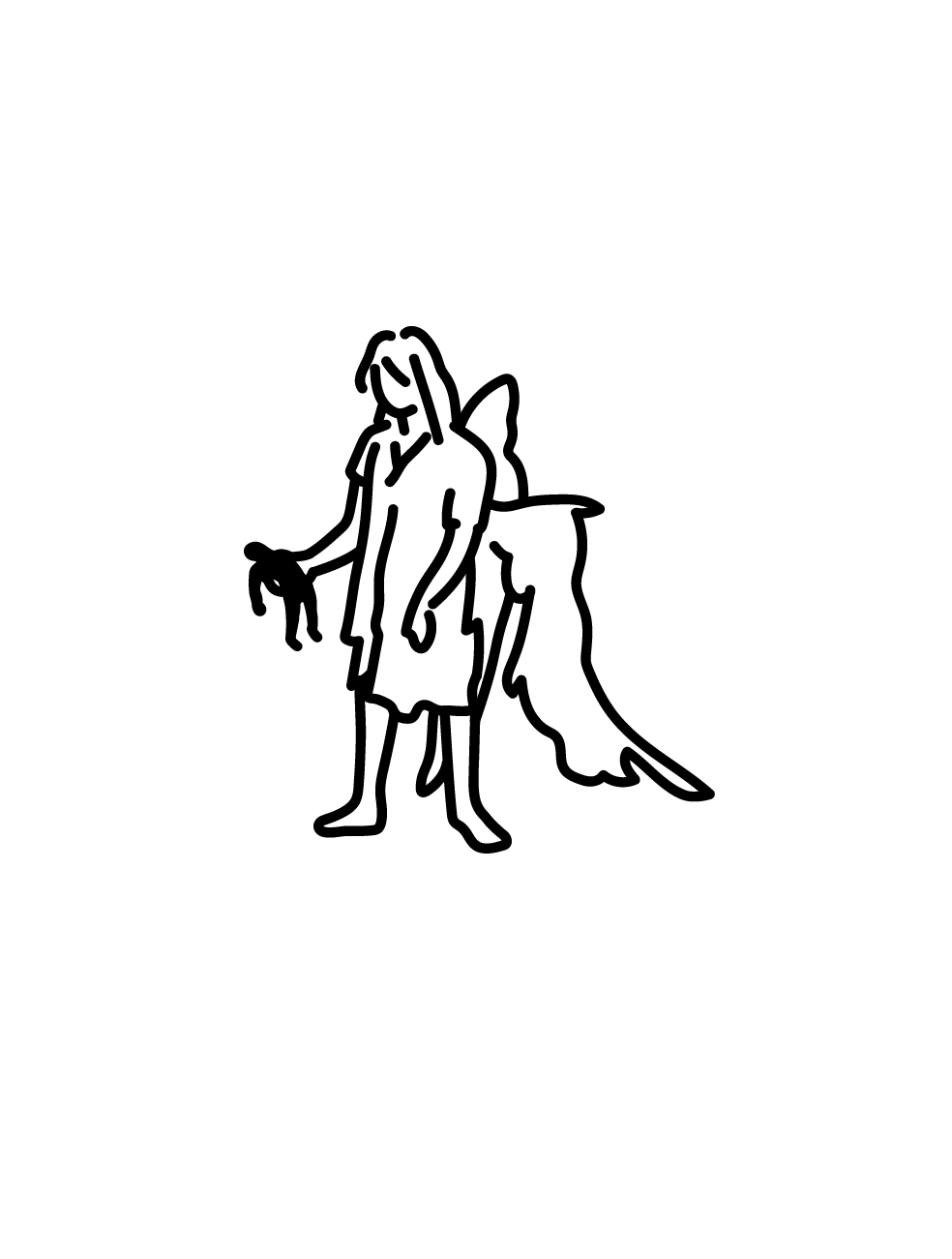

A Klee painting named “Angelus Novus” shows an angel looking as though he is about to move away from something he is fixedly contemplating. His eyes are staring, his mouth is open, his wings are spread. This is how one pictures the angel of history. His face is turned toward the past. Where we perceive a chain of events, he sees one single catastrophe which keeps piling wreckage upon wreckage and hurls it in front of his feet.

Ninth thesis

One can imagine Walter Benjamin’s words about the mounting wreckage from an encompassing catastrophe being murmured behind scene after scene from Route 181. Other sentences too from this enigmatic montage-essay, which shimmers at the crossroads of historical theory, political analysis and oracular poetry, chime with significance for our current situation.

Benjamin wrote Theses on the Philosophy of History — his last fully-realized work, and perhaps his greatest achievement — following his release from a French internment camp in the spring of 1940, approximately six months after the signing of the Hitler-Stalin non-aggression treaty and the subsequent German invasion of Poland, less than six months before his suicide aged 48 in thwarted flight from the Nazis. While world events unquestionably precipitated the essay’s creation, it was also the culminative entry both in a dialogue he’d been carrying on for nearly two decades with his close friend, Gershom Scholem, the humanist scholar of Kabbalah, and in his independent explorations of the relationship between theological hope and revolutionary politics. In a letter to Gretel Adorno (the erudite chemist wife of the Frankfurt School philosopher Theodor Adorno), he describes the theses as « a bouquet of whispering grasses. » He had no intention of even trying to publish them, he remarked, since doing so « would be a perfect recipe for enthusiastic misunderstanding. »

In its posthumously published form, the essay consists of eighteen numbered theses, plus two appendices, each of which possesses both autonomous gravity and interlinking vectors to the work’s other sections. As Benjamin remarked, no single part of the work serves as a transition or stage in a sequence: they instead constitute postulates in a galvanic matrix.

Although it is impossible to reduce the Theses to a single argument, a key opposition structures the text: mere historicism that takes a linear, teleological view of history, and which Benjamin found fatally lacking, versus an historical materialism that he saw as fertile in its revolutionary potential. He tied the former to Germany’s Social Democrats (a party with parallels to today’s mainstream Center-Right and Center-Left governments), whose uninterrogated faith in limitless « progress » had helped strip away older, more cooperative social patterns, less infected by monetary ambitions, that might have formed a bulwark against Fascism. The Social Democrats had painted themselves into a corner by feckless lamentation: continuing to express « amazement that the things we are experiencing are ‘still’ possible in the twentieth century, » while failing to reckon with the fact that the prevailing state of emergency was « not the exception but the rule » for history’s oppressed. The latter discipline — historical materialism — Benjamin associated with the heterodox Marxist idiom that he’d developed by fusing his readings in communistic theory with a radical theological vision evolved through conversations with Scholem.

It’s impossible to overstate the layered depth of Benjamin and Scholem’s exchange. Though Scholem was five years his junior, Benjamin considered him more than an intellectual peer — as in fact his only conduit to a meaningful knowledge of Jewish existence.

One idea encountered through Scholem which proved abidingly influential to Benjamin was the medieval Jewish philosopher Maimonides’ theory that our everyday reality is already pregnant with eternity and its divinely sanctioned attributes (including justice). Quoting Maimonides, Scholem wrote, « ‘It cannot be understood that the world to come is not yet here, that it will come only after the decline of this world…the world to come is continually becoming.’ »

This notion replaces the call for a violent, even apocalyptic response to rampant injustice with the summons to shift one’s attention to something that is still being born: an indeterminate possibility with its roots in a deeper past than the one being nostalgically marketed to justify the enfranchisement of barbarism. Here we might detect hints of a response to Route 181 and the present-day cataclysm other than abject despondency or an invitation to further bloodshed. « The mystics, where they have not fallen prey to the political revolutionary-ism of the apocalyptics (the politicians of Judaism), define the messianic kingdom with infinite precision as the ‘world, which is continuously arriving’ — the eternal present, » Scholem declared in an essay begun in 1919.

Klee created the small image of the Angelus Novus — an oil transfer drawing with a watercolor overlay — in 1920. Walter Benjamin purchased it the following May. Scholem described its role in Benjamin’s existence as both « a picture for meditation » and the « memento of a spiritual vocation » whose significance evolved over the two remaining decades of his life. Apart from what the image meant to him personally, Benjamin’s final interpretation of the artwork proved so compelling and beguiling that it has made it virtually impossible to look at the angel except through the lens of the late Benjamin’s gaze — to see it, that is, as an angel of anything other than history.

The thesis goes on to recount the angel’s predicament:

The angel would like to stay, awaken the dead, and make whole what has been smashed. But a storm is blowing from Paradise; it has got caught in his wings with such violence that the angel can no longer close them. This storm irresistibly propels him into the future to which his back is turned, while the pile of debris before him grows skyward. This storm is what we call progress.

Even in its brevity, this dense, metaphysical fable is riddled with puzzles: Why is the destructive storm hurtling toward the angel from Paradise? Yet the lyrical mystery of this idea acquires politico-historical resonance when arrayed dialectically with other sections of the essay. While there are no definitive solutions, it seems likely that Paradise here represents the utopian future of abundance and bliss promised by those advertising themselves as the vanguard of « progress » — commodified, technological, reassuringly bourgeois.

Moments such as that coupling of the « single, ongoing catastrophe » with the angel’s subjection to the consuming storm labeled as progress help explain why Klee’s drawing became an icon for structurally discontented exponents of anti-capitalist leftist thought. This sacrosanct quality remained undisturbed by the fact that the picture was a minor work in Klee’s oeuvre and — until Benjamin’s essay became well known long after his death — was only ever seen by a small coterie of the intellectual elite.

Moreover, the drawing might never have acquired its importance for Benjamin himself had it not been for two crucial, early interventions by Scholem. The picture thereby became the medium for an internecine debate between the two men about the weight of moral obligations to ancestral tradition relative to a broader human responsibility.

Benjamin bought the picture in Munich while visiting Scholem, who was studying there and at work on an essay about kabbalistic poetry that focused on the hymns of angels. He spoke with Benjamin regularly about his findings. While angels in Judaism typically function as intermediaries between the divine and mundane realms, in certain mystical works they also personify aspects of God’s potency and make manifest a supernal value system. Jewish angelology captivated Benjamin, in particular a Talmudic legend about the angels’ poignant ephemerality, which stated that each one was created to sing its own distinctive lyric in the presence of the divine before disappearing forever. The idea of impermanence as a virtue, philosophically, aesthetically and politically, always inspired Benjamin. No one who looked seriously at the state of things could champion stability, he believed, just as adopting a single, stationary perspective was antipathetic to socially constructive thinking and artistic inventiveness alike.

Benjamin would later transpose this idea onto the fabric of history — calling for a form of interpretation that placed contemporary auditors of the past in something like the position of God listening to the angels — but with the space of heaven itself in jeopardy. When, he writes in his Theses that « the true picture of the past » can only be seized in its vanishing, the picture of the past is like the angel’s song: the observation of its disappearance is a reflection on the emergency we ourselves are experiencing. Instead of praising the divine glory, we articulate our position in a firmament glowing with the fires of innumerable, interdependent, cosmic calamities. « Only that historian will have the gift of fanning the spark of hope in the past who is firmly convinced that even the dead will not be safe from the enemy if he wins, » Benjamin avows in the sixth thesis. « And that enemy has not ceased to be victorious. »

When Benjamin left Munich to return to Berlin, he asked Scholem to hold onto the Angelus Novus for the time being since his future living arrangements were uncertain. Scholem hung it on his wall and composed a poem in the first-person voice of the angel for Benjamin’s birthday on 15 July 1921.

Scholem’s tuition in kabbalistic and Talmudic angelology, combined with the birthday poem, exerted a lasting, if ambiguous influence over Benjamin’s fascination with the picture. In the last year of his life he took a verse from Scholem’s 1921 poem as the epigraph for his ninth thesis on history:

My wing is posed for flight,

I would like to turn back,

If I stayed timeless time,

I would still have little luck.

Benjamin’s extraction of this particular verse in order to recontextualize the lines with his own allegory about the Angel of History appears to subvert their original meaning. In Scholem’s poem, Klee’s angel reveals itself to be a figure of profound historical impatience. (It’s not incidental that Benjamin was seen by many who knew him, Scholem among them, as a person of « epic patience, » while Scholem himself was notoriously imperious and headstrong.) « I hang on the wall/and look no one in the eye, » the poem begins. Scholem’s angel proclaims that he is heaven sent, and that though people of the town to which he’s been dispatched (Munich, conceivably) fall within his domain, the angel takes little interest in the local situation. He is thinking perpetually of « the world from which I come, » which is « measured, deep and clear. » The angel itches to go home because, the poem suggests, the human world to which he has been sent is a lost cause. No matter how long he might remain he can’t sway this society. « I know what I must announce, » he says, « and many other things as well. » Here knowledge is invoked to justify disengagement. Like the prophet Jonah (the focus of an early Scholem essay) the angel sees his mission as pointless since people don’t really change and events will take their divinely ordained course regardless. Nor will he allow himself to be instrumentalized by humanity as some esoteric talisman whose presence in itself vindicates hopefulness. « I am an unsymbolic thing, » the angel declares in the poem’s concluding verse. « What I am I mean. »

When Scholem wrote these lines, he’d already made up his mind to get out of Germany and, as a committed Zionist (in a cultural if not a political-sovereignty-driven sense), the place he meant to travel to was Jerusalem — the Biblical wellspring of Jewish identity and a city associated with the Lord’s eternal presence. His sense of the imperative of this « return » was heightened by witnessing up close in Munich what he described as incipient Nazism. As Scholem wrote in his memoirs, even as early as 1921, « The atmosphere in the city was unbearable. » Already, « there was no disregarding the huge, blood-red posters with their no less bloodthirsty text, inviting people to attend Hitler’s speeches. » The Jews’ existence in Europe was viewed by this public as parasitically colonizing their host countries, even as their presence in Palestine would later come to be seen as a European colonial project. While Scholem’s decision to leave Germany made him feel less susceptible to this gathering menace, « it was frightening to encounter the blindness of the Jews who refused to see and acknowledge all that. » In Scholem’s eyes, Walter Benjamin was among those resisting the personal implications of Germany’s psychopathological political currents. When Scholem moved to Palestine in 1923, Benjamin gave him as a parting gift a scroll containing an essay he’d written about the decline of Germany. « Over and over again it has been shown that the way society clings to normal (but already long-lost) life is so fierce as to frustrate the truly human use of intellect and foresight, even in the face of drastic danger, » Benjamin wrote in this text.

You’re reading this essay for free. With a membership, you can read the full magazine, and you get access to our fabulous Library.

Here’s our offer: 3 months unlimited digital access + 1 print edition for € 38,00 € 19,00

You’ll get Issue Eleven in print as your first magazine, right to your mailbox.

Looking back on their friendship decades later, Scholem wrote, « it was hard for me to understand what could keep a man who had written this in Germany. » Moreover, given Benjamin’s declared investment in learning more about Judaism, Scholem was convinced that he could be brought to recognize his destiny as a scholar of Jewish metaphysics, which might eventually impel his own migration to the Holy Land.

In this light it’s possible to read the loftily detached, home-yearning angel in Scholem’s poem as a projection of his own Zionist self (« what I am I mean ») and to speculate that Scholem wanted Benjamin to understand the angel’s message as admonitory: There was no point staying on in Europe in the vain hope of inciting social change. The two of them would forever be aliens in Germany, both because the Germans would never genuinely accept them and because Jewish identity was meant to be fully inhabited — realized concretely and spatially as an essential property of selfhood.

When, almost twenty years later, Benjamin enlisted Scholem’s poem to counterpoint his own reflections, he chose the verse in which Scholem’s angel announces his readiness to depart — but then presents us with an angel who is unable to fly because his wings are trapped in a comprehensive historical nightmare that is forcing him to move in the opposite direction from that in which he yearns to travel. As the Angel of History, this figure is the epitome of « a symbolic thing » whose meaning emerges only mimetically, through a chameleon-like relation to the collective experience of unfolding, epochal events. Benjamin’s angel could not be more concerned with the human condition. He doesn’t even broach the idea of returning to Paradise — whence, after all, the storm of progress originates. This angel wants to stay amidst the smashed things and attempt to repair them.

Benjamin may have intended that image as a reproof to Scholem, who had taught him all he knew of Jewish mysticism, including the core principle of tikkun olam (the mandate to repair the broken world), along with a theory of justice that precluded the right to enact final judgement on any society, no matter how tainted, given the irreducibly multifarious, contradictory expressions of life every population must contain.

Scholem’s position as expressed through the angel could thus be accused of betraying the call to universal empathy he’d once defended. When Benjamin composed his Theses, the winds of historical disaster were caught in the wings of countless contemporaries who could no longer control their own movements, however eager they might have been to escape. Benjamin transforms Klee’s angel from a figure of exceptionalism — God’s chosen one — into an emblem of vulnerable humanity’s shared victimhood.

Yet Benjamin’s reflections on Klee’s angel do not constitute the climax of his essay, nor was he advocating resignation before titanic, traumatic circumstances. To the extent that the essay may be said to reach a conclusion, it seems informed by another Talmudic parable that Scholem would have made known to him: On what is considered the most tragic day in Jewish history — the day of the Temple’s destruction — the Messiah was also born. In Scholem’s gloss, the Messiah « is always already present somewhere » in a state of occultation, and his emergence from this state of concealment is constantly possible. « Beginning at the moment of the deepest catastrophe there exists the chance for redemption. ‘Israel speaks to God: When will You redeem us? He answers: When you have sunk to the lowest level, at that time will I redeem you.’ »

Disaster and salvation are thus twinned in Judaism. This idea complicates any effort at co-opting history in the service of a monolithic narrative of righteous national ascendancy. Humility, even total debasement, rather than any sort of divinely sanctioned triumphalism prefaces the Redeemer’s appearance. (Hence the sentiment voiced in the Talmudic tractate Sanhedrin, « May he come, but I do not want to see him. ») The dualistic nature of history’s inflection-hours only compounds the moral challenge posed by Gaza and other sites of cascading devastation.

III

To articulate the past historically does not mean to recognize it ‘the way it really was’…

It means to seize hold of a memory as it flashes up at a moment of danger.

Sixth thesis

The image of the angel spellbound before a rising heap of ruins, unable to fulfill its yearning to remain in place repairing everything that’s been ravaged by the onslaught of power because of a wind designated as « progress » which keeps blowing it further into the future, is one we may feel we have glimpsed in our own mirrors recently. We raise our arms as if in acknowledgement that we are under arrest by the times.

But while the sense of horror might impart a solidarity in anguished helplessness, Benjamin did not want us to freeze on that vision of petrification, which arises almost exactly midway in his essay, and is succeeded by numerous passages that seem to contrast the angel’s frustrated volition with instances of active resistance and, finally, the valorization of a state of dynamic anticipation.

For years Benjamin had expressed his contempt for the passive posture of what we might call progressive melancholia. In a 1931 essay, he lambasted the left-wing intelligentsia’s proclivity for seizing onto ideological fads whose political relevance was depleted by « the transposition of revolutionary reflexes…into objects of distraction, of amusement, which can be supplied for consumption. » In place of real determination to induce change, these comfortable dabblers in rhetorical elegy exuded a « know-all irony, » which turned « yawning emptiness into a celebration. »

We must beware the hypnotic quality of that appalled, paralyzed angel of history, not only if we are among those actively thrashing in the maelstrom, but even as aghast witnesses o disaster. It’s worth asking the question then: what might Benjamin have wanted us to make of the angel?

If the angel of history cannot redeem, shield, or even transmit news to us, we should consider the possibility that it may instead be appealing for help from outside — from us. The angel is overwhelmed by the scale of atrocity, but perhaps our own capacity to taxonomize history’s crimes and precious, contrary instances of active compassion can liberate it from its state of bleary transfixion. We may find a clue as to what Benjamin is proposing in a passage from « Central Park, » another multi-part, non-linear essay written in 1939, when Benjamin still believed he would be able to escape to America under the auspices of Max Horkheimer’s Institute for Social Research. « The course of history, seen in terms of the concept of catastrophe, can actually claim no more attention from thinkers than a child’s kaleidoscope, which with every turn of the hand dissolves the established order into a new array, » Benjamin wrote there.

The image of order itself proves to be the governing illusion fabricated by society’s dominant enterprises, he contends. The frame of catastrophe is useful only as a device for shattering and reconfiguring our view of things — it should not itself become the focus of our gaze. The kaleidoscope itself must be smashed as a prerequisite to restoring what’s been destroyed through barbarism.

It’s precisely the impression of a magnifying, indiscriminate disaster that has rendered the Angel of History numb before the torrential unleashing of power-consolidating, so-called progress — transforming it from a guardian figure into a character requiring earthly assistance to survive. What would it mean not to be saved by but to become the savior of the angel?

One notion this perspective warns us against is that promoted, for example, in the speech Netanyahu gave at the start of the ground invasion of Gaza in late October 2023 when he declared to the Israeli people, « Never again is now. » Or, for that matter, the pronouncements of those who see Israel’s genocidal campaign in Gaza as a seamless continuation of the 1948 Naqba, as (along with all subsequent Palestinian afflictions) an indistinguishable part of one single catastrophe. These positions lead either to a sense of powerlessness, as evinced by Klee’s Angel in Benjamin’s thesis, or to the invocation of some reciprocal angel of destructiveness who might annihilate the adversary before that adversary consummates its own annihilationist project.

As opposed to the murky homogenization of historical trauma, Benjamin advocates placing events in charged alignment to heighten awareness of their unique features together with their correspondences. Through forensic specification to emancipatory disenchantment, he seems to say. But the disenchantment of history Benjamin proposes may ultimately catalyze another form of transcendent intercession whose nature cannot be fully known from our temporal vantage-point.

IV

We know that the Jews were prohibited from investigating the future. The Torah and the prayers instruct them in remembrance, however… This does not imply, however, that for the Jews the future turned into homogeneous, empty time. For every second of time was the strait gate through which the Messiah might enter.

Appendix B

In the summer of 2025, when even those who’d long resisted the word « genocide » were finding the word unavoidable as a description of what was transpiring in Gaza —

In the summer of 2025, when protests against the Palestinians’ persecution were reg-

ularly met in Berlin’s Neukoelln neighborhood and elsewhere across Germany with savage police suppression, even as the Chancellor was saying that Netanyahu would not be arrested if he came to visit Germany, despite his country’s obligation to detain him on the grounds of the International Criminal Court warrant for his arrest, notwithstanding the fact that the ICC had evolved out of the Nuremberg trials spawned by Germany’s own perpetration of genocide —

In the summer of 2025, when it was clear that, in Walter Benjamin’s formulation, « the assumption that things cannot go on like this will one day find itself apprised of the fact that for the suffering of individuals as of communities there is only one limit beyond which things cannot go: annihilation — »

In July of 2025, when I watched Route 181 and returned over and over to the Bode Museum to look at Klee’s angel, even while reading and re-reading Benjamin’s Theses, it seemed as if the Angel of History could only be rescued from « progress » by returning it to some version of the past distinct from today’s nostalgic state-building enterprises and revanchist ideological projects. This return would be to the past as a space offering simple models of trans-tribal neighborliness, in which shared rites of passage might prove sufficient to bless life with a sense of miraculous richness. Instead of vowing « never again » for one’s ethnic group or swearing to make one’s country « great again, » we might think what would be entailed in making ourselves human again, in the sense just of being more humane.

The second section of Khleifi and Sivan’s documentary ends with a scene of Palestinians defying military blockades and exclusion zones by picking their way over rugged terrain on less surveilled paths to celebrate a wedding. The guests are dressed in an array of formal and traditional garb, and there is great dignity in their precarious passage through the rocks, dust and dirt. In a discussion held after this scene was shown, one audience member commented on the poignant beauty of these people’s refusal to relinquish collective rituals to the occupation’s systematic constriction of everyday life. Before long, a young woman broke in, rejecting that inspirational viewpoint. This person was in fact Tyme Khleifi, the niece of the filmmaker Michel Khleifi, who’d helped organize the screening. She herself was now living in Berlin, working with the Barenboim-Said Academy and the East-West Divan orchestra, two organizations whose commitment to egalitarian coexistence has been exemplary.

Khleifi noted that she in fact did not respond to these images with a sense of reverential awe at the celebrants’ bravery. She reacted with outrage and bitterness. Why were these adults being made to struggle so grotesquely simply to attend a wedding? Why did grown men and women have to scramble through the dust on bad paths in perilous circumstances just to assemble for a peaceful celebration? Why were young Israeli soldiers given the power to humiliate the elderly? Why were these ordinary civilians being put through this demeaning ordeal?

After Khleifi made this point, others raised their voices to agree and to dispute. Both views were true — the profound poignance of the surviving grace and the inexcusable oppression, the two came doubled like theological wonder and Marxist analysis in Benjamin’s essay.

Then the conversation turned to Gaza. No one conflated the situation of the wedding guests 23 years ago with that of those now suffering in Gaza, but they constellated the events — speaking of particular families and their efforts at resistance in successive periods of entwined yet heterogeneous catastrophe. Others discussed the continuing exchanges between Jews and Palestinians who were looking beyond the moribund proposals for a geographical two-state solution to something more imaginatively confederated, in which side-by-side neighborly coexistence corresponded with more intricate designations of citizenship and legal jurisdiction. The boundaries between cultures and particular identities could be retained, but shown also to be permeable through certain shared institutions and traditions of hospitality with their own long lineages in disparate cultures. « One reason why Fascism has a chance is that in the name of progress its opponents treat it as a historical norm, » Benjamin wrote in the eighth thesis.

The conversation in that room, in a building at the rear of a leafy courtyard in the city where Scholem and Benjamin began their lives and friendship and where the war-torn exile of their later years was engineered, seemed to echo what Benjamin called for throughout the Theses on the Philosophy of History. Different moments, not only 2002 and 2025, but also 1945 and 1948, were narrated across a grid in which time moved multidirectionally. The type of historians Benjamin advocated for would stop « telling the sequence of events like the beads of a rosary. » Instead, they would learn to grasp the constellation that their « own era has formed with a definite earlier one. » In this way, Benjamin proposed, an historian would create a conception of the present as « ‘the time of the now’ which is shot through with chips of Messianic time. » That’s to say, events were neither merged nor atomized, nor viewed teleologically, but rather were placed in unsettling relation.

After the screening of Route 181, when I went for a last visit to the Bode Museum’s « Angel of History » exhibit, I found myself wandering between numerous other sculpted, carved and painted angels hovering around that vast building. There were angels flying and kneeling while prettily framing Jesus on the cross or Jesus rising from the tomb, or Mary and baby Jesus. Angels holding garlands, medallions and musical instruments. And also angels subduing demons, ascending ladders made of light-beams. Almost all of them were nearly expressionless. I recalled a remark by a rabbi I know who described angels in the Hebrew Bible as being « God bots » — issuing forth only to execute the Divine will.

Viewing the museum’s permanent collection of angels put Klee’s achievement in perspective. The Angelus Novus — grotesquely proportioned, with scrolly hair, huge eyes, a warped mouth and what may be an erect phallus rising pink from the juncture of its spread wings and stunted torso — projects and demands high attention. So far from being bot-like, this angel is a testimony to inflamed subjectivity.

Ordinarily Klee’s picture sits in the Israel Museum, to which it was donated by Scholem’s widow, Benjamin having bequeathed it to Scholem together with his relevant manuscripts. Here it was being shown alongside various other angels from Berlin museums damaged or destroyed during the Second World War. This presentation of the Angel of History seemed to consecrate mourning as evidence of civilization’s persistence, however politically inert or philosophically spectral. As I stood before the picture, in the midst of the broken Berlin angels and loop footage from Wim Wender’s Wings of the Angel, I remembered hearing from an acquaintance who’d visited the exhibition earlier. She’d witnessed a woman going up to the Angelus Novus, genuflecting and making the sign of the cross before rising up and leaving the gallery. In a terrible way this seemed the appropriate gesture to the fetish-idol style of its display. The Angelus Novus, thronged by pious pilgrims, had been thoroughly ghettoized within the context of the Nazi destruction at the very moment when another sea of ruins (rationalized by the Israeli state as a prophylactic operation against the repetition of that earlier Holocaust) was rising before our gaze. The wings of this angel were unable to open and close because they were drooping like sails in a windless calm — the glassy doldrums of artificially delimited historical valencies.

As I stared, I seemed to see the angel widening its eyes and throwing up its arms to say, like the man from Morocco at the beginning of Route 181, « What do you want from me? » And also, « Why am I here? », and « Set me Free. » Everything in the exhibition smeared into one-dimensional historicism.

Klee himself understood the call to represent multiplicity, the way that depicting the variations of reality might stimulate the valuation of life. The Angelus Novus is an early entry in Klee’s series, but in his later years, as the world picture was darkening, up until his death in 1940, Klee created dozens more idiosyncratic angels. Some are terrifying, some comic, others lyrically evocative: Angel full of Hope; Angel Brimful; Angel, Still Groping; Whence? Where? Whither?; Angel Militans; Angelus Dubiosus; Child-Eater; Angel in the Making; Poor Angel; Vigilant Angel — until the viewer suspects that any protective or annunciatory capacities these strange beings possess derives from their demonstration of the sheer capaciousness of the human imagination — a creativity so expansive that it may yet find the breadth to shelter two distinct, interrelated peoples in Israel-Palestine. With respect to the angels, Klee once observed, « everything is the same as it is here, just angelic. »

Perhaps the only way out of the present dilemma is to take all the unsynchronized clocks of the region and confabulate a montage-sidereal-map of the moments they idealize or excoriate. To create some extraordinary art night-sky canopy of Israel and Palestine’s discontinuous time-pieces, in order to see what stories can be told about these constellations that might slit open the darkness.

There is a kind of waiting that exists at an infinite remove from doing nothing because it’s devoted to scrupulously documenting the lost and endangered, a form of activist archiving that might serve as the foundation for one day building a future antithetical to that nourished by the linear storm known as progress. This does not mean bearing witness solely to disaster, however. We need also to register the words and actions of those who know that relationships between peoples have taken different, more symbiotic forms at other points in history.

When Benjamin writes of the Jews becoming instructed in remembrance through Torah and prayers, he is speaking of memory as a learned, collective art not a private possession. If too few Israeli Jews today remember even the names of the Arab villages they’ve come to occupy, and too few on either side of the conflict recall the examples throughout history of Arab-Jewish coexistence, that doesn’t prevent these stories from being taught, until the paradigms begin to be assimilated, entering into a discourse of shared experience where the history of another future might start to germinate. The language necessary to bridge the abyss between peoples already exists and needs to be rediscovered in the basic human gestures that incarnate our common interest. This is not some nostalgia for a mythic, golden past, but a yearning to live again in accord with the principle verbalized by Khleifi and echoed by his Jewish-Tunisian interlocutor, Every person is human. What might follow were we to truly absorb that viewpoint? « To allow the messianic world to break through, the perspective of redemption needs only a virtual shift, » Scholem wrote in a youthful essay on justice.

If we take the concluding sequence of Benjamin’s Theses as prescriptive it’s possible to infer that what Benjamin would enjoin at this moment is unrelenting remembrance as an act of resistance perpetrated through the past in the name of tomorrow — as if « every second of time was the strait gate through which the Messiah might enter. »

You’re reading this essay for free. With a membership, you can read the full magazine, and you get access to our fabulous Library.

Here’s our offer: 3 months unlimited digital access + 1 print edition for € 38,00 € 19,00

You’ll get Issue Eleven in print as your first magazine, right to your mailbox.