Proto: How One Ancient Language

Went Global

Laura Spinney

(Bloomsbury, 2025)

Around five thousand years ago, along the northern bank of the Black Sea where the soil was rich and feather grass plentiful, the nomadic Yamnaya people sang songs about the heroes who slayed dragons. A warrior named Trito is given cattle by the gods, but this most helpful of gifts is stolen by a three-headed serpent. Fortified by an intoxicating potion supplied by the Sky-Father, Dyeus, Trito is victorious over the snake and regains his cattle. A familiar story. In the Rig Veda, the nearly 3500-year-old Sanskrit scripture, the hero Indra « slewest Vrtra the Dragon who enclosed the waters ». In the Bibliotheca, a compendium of Greek myth from the first or second century AD, Hercules « chopped off the immortal head » of the serpentine Hydra, « and buried it, and put a heavy rock on it, beside the road that leads through Lerna to Elaeus. » Snorri Sturluson in the thirteenth-century Icelandic Prose Edda describes Thor’s tussles with a serpent who « spits out poison and stares straight back from below. » The hero of the Anglo-Saxon epic poem Beowulf, « who may win glory before death », defeats the fearsome Grendel; St. George killed his dragon, too.

The philologist Calvert Watkins, in How to Kill a Dragon: Aspects of Indo-European Poetics (1995), used « the serpent or dragon slaying myth » to identify a common Indo-European poetics that has spread from present-day Ukraine to India and Ireland. That a variety of seemingly disparate tongues are related, from English to Urdu, has been a linguistic mainstay for generations, but that these tongues often repeated the same stories remains a wondrous fact. For centuries, scholars have speculated about these shadow storytellers at the West’s origins, but today’s advances in genetics and archaeology seem to have told us who they were and where and how they lived. And yet: there’s data, and then there are the stories we ourselves tell to interpret that data, and thereby understand where we come from. Hypothesizing a language called « Proto-Indo-European » — and then imagining a people to be called « Proto-Indo-Europeans » — has always involved myth. A disciplined mythography traces those dragons across seemingly distant and distinct cultures, to powerful effect. The imagined anthropology of these original peoples, though, has a bit of constructed fabulism about it as well.

What do the Proto-Indo-Europeans mean to us today?

The discovery and subsequent restoration of a Proto-Indo-European language that was the origin of everything from Sanskrit to Gaelic, Farsi to Welsh, Icelandic to Greek, Polish to Sardinian, Yiddish to Romani, Occitan to Norwegian, Anatolian to Catalan, is among the greatest intellectual victories of the last few centuries. Much of what’s been discovered since the nineteenth century is standard in any comparative linguistics course, but there is still something wondrous about a chain, at once evolutionary and transcendent, binding an English or Dutch-speaker back to a now-forgotten Bronze Age culture, and to a common language whose last living speaker died six millennia ago and of which there are no written records. It was a philological revolution — a revolution in the scientific sense, analogous to Copernican theory in astronomy and Darwinian natural selection in biology, with implications just as radical for how we understand our place in the world.

Like Copernican heliocentrism, the idea of a common language challenged the Book of Genesis’ assertion that the scattered languages of man derived from God’s punishment of human hubris in constructing the Tower of Babel. In the Babel myth, the various tongues all emerge ex nihilo and were (by punitive design) mutually incomprehensible. Of course the mythic-ness of Babel was already intuitive: after all, an ancient Roman and his Gaulish enemy would cry out on the battlefield respectively to mater and mathir, and a Sanskrit priest might think of his fellow initiates as being brotherly bhraters, and the stranger welcomed into a Neolithic Black Sea yurt was a gostis, while to an English-speaker they’d be a guest. The relationships are encoded into the syllables. There are thousands of such cognates across the Indo-European languages that demonstrate morphological descent.

Other traits of Proto-Indo-European endure in languages from Urdu to Czech — similar conjugations across person, number and tense, for instance. « The constant and automatic use of such categories generates habits in the framing and perception of the world, » the anthropologist David W. Anthony maintained in The Horse, the Wheel, and Language: How Bronze Age Riders from the Eurasian Steppes Shaped the Modern World (2007). The claim is that we moderns repeat the « perceptual habits and categories of a small group of people who lived in the western Eurasian steppes more than five thousand years ago. » Hidden within our grammar and syntax, our vocabulary and our prosody, are traces of those lost ancestors. Or, to use Anthony’s geological metaphor, « the words we use today » are « fossils » of an earlier epoch’s vocabulary. A visit to your local delicatessen proves the point: when at a New York bagel place you ask for an everything with lox, that word for smoked salmon echoes the « lachs » of German, the « lax » of Icelandic, even the « laks » of Tocharian (a language once spoken near China). Such words are vestigial cognates, language’s enduring coelacanths, the ancient fish thought to be extinct until it was found swimming. Some fifteen-hundred words of Proto-Indo-European have been deduced in this manner, from the most obvious core vocabularies (numbers, family relationships) to the more abstruse.

Ursprache

By The Editors

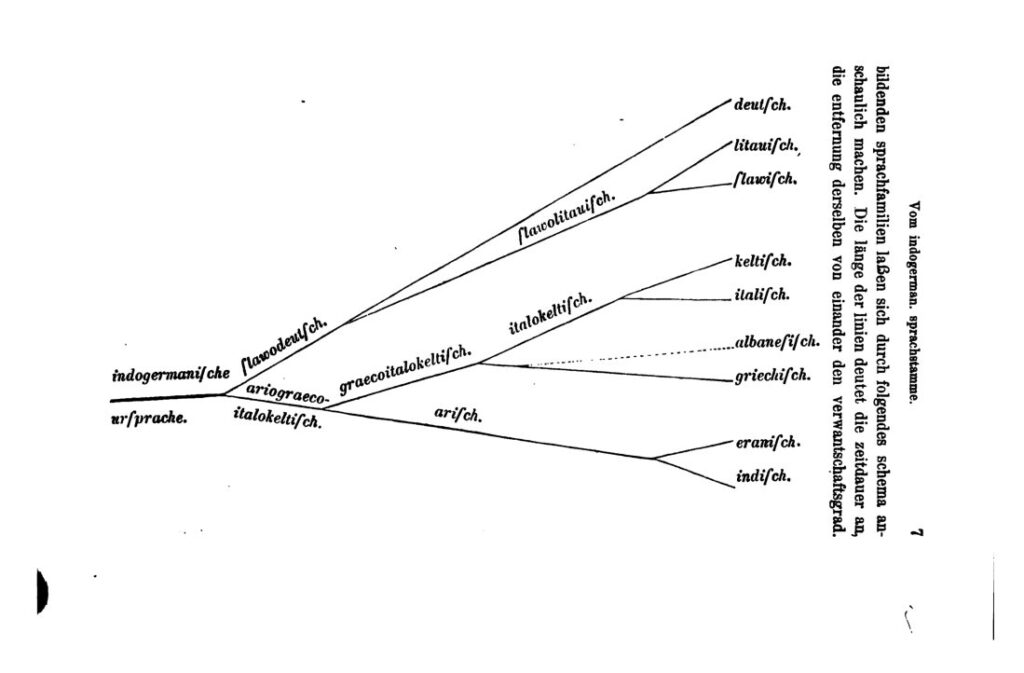

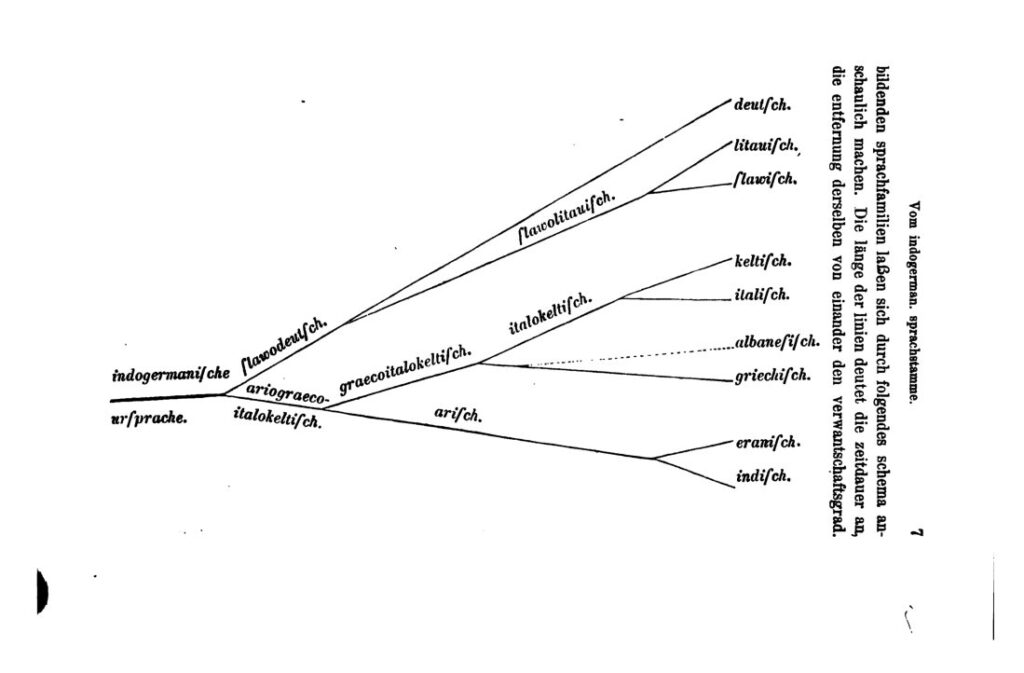

The language tree from the German linguist August Schleicher’s Compendium der vergleichenden Grammatik der indogermanischen Sprachen (1861; translated in 1874 as A compendium of the comparative grammar of the Indo-European, Sanskrit, Greek, and Latin languages), tracking the branches that had sprung from an indogermanische root: deutsch, litauisch, slawisch, keltisch, italisch, albanesisch, griechisch, eranisch, indisch.

Schleicher was also the first to try his hand at writing in that hypothetical ursprache that would later be called « Proto-Indo-European » (« Eine fabel in indogermanischer ursprache », Beiträge zur vergleichenden Sprachforschung auf dem Gebiete der arischen, celtischen und slawischen Sprachen, 5:2 (1868), 206-208). In 1868, « partly to show that it is possible, albeit with difficulty », and partly to satisfy a whim, he produced a « fable » about a shorn sheep and some long-suffering horses. Though constrained by « the scarcity of words », it still has a sad charge:

Avis akvāsas ka.

Avis, jasmin varnā na ā ast, dadarka akvams, tam, vāgham garum

vaghantam, tam, bhāram magham, tam, manum āku bharantam. Avis

akvabhjams ā vavakat: kard aghnutai mai vidanti manum akvams

agantam.

Akvāsas ā vavakant: krudhi avai, kard aghnutai vividvant-svas:

manus patis varnām avisāms karnauti svabhjam gharmam vastram

avibhjams ka varnā na asti.

Tat kukruvants avis agram ā bhugat.

Schleicher’s translation had to splice in the articles and prepositions, which the reconstructed original language didn’t offer:

[The] sheep and [the] horses.

[A] sheep [on] which wool was not (a shorn sheep) saw horses driving [a] heavy cart, carrying [a] great load, carrying [a] man quickly. [The] sheep said [to the] horses: [The] heart is constrained [within] me (I am heartily sorry), seeing [the] man [driving] the horses.

[The] horses said: Listen, sheep, [the] heart is cramped [in the] seeing-having (we are heartily sorry, since we know): [the] man, [the] master makes [the] wool [of the] sheep [into a] warm garment [for] himself and [the] sheep is not wool (but the sheep have no more wool, they are shorn; they are even worse off than the horses).

Having heard this, [the] sheep turned (escaped) [into the] field (it

headed for the hills).

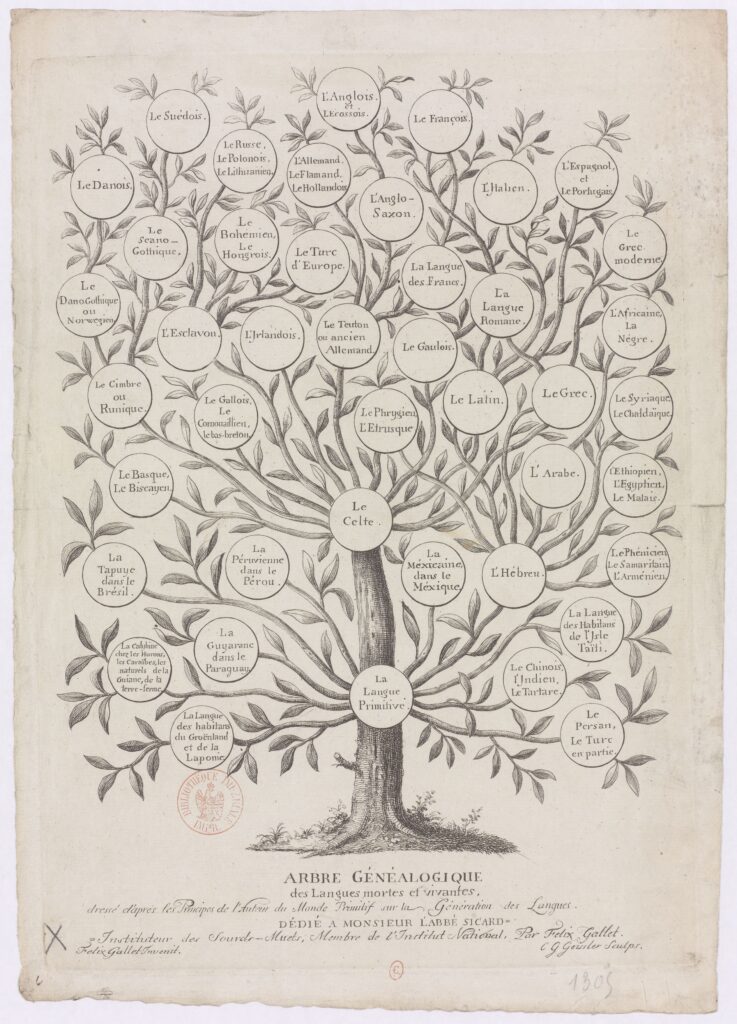

Dante Alighieri first noted in his 1305 treatise De vulgari eloquentia that languages in Iberia, France and Italy could be categorized by how they say « yes », between those that use òc, oi, or si. He hypothesized a common Latin ancestry for what would later be classified as Romance languages, already beginning to think evolutionarily when it came to how humans communicate. Much of the work surrounding the subject today is done by those who would consider themselves scientists, but the intellectual triumph that is the resurrection of Proto-Indo-European has its origins in the humanities. Dante’s humanism, that is to say, was proto-scientific in this particular aspect. The historian of the humanities James Turner, in Philology: The Forgotten Origins of the Modern Humanities (2015), recounts how as early as the sixteenth-century, merchants observed similarities between languages seemingly as disparate as Greek and Sanskrit (a rediscovery of something that the ancients also knew). If things now thought of as simply « scientific » discoveries — across linguistics, archaeology, and even genetics — began with poetry, then the humanities still have something crucial to say about the Proto-Indo-Europeans.

It was the polymath Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz — let’s call him the last of the true Renaissance men who could know everything — who suggested, in 1710, that the broad sub-families of European languages (Italic, Germanic, Celtic, Slavic) had a common ancestor, though he used the term « Japhetic, » after the son of Noah whose descendants were thought to have populated Europe.

The first genuinely systematized charting of these relationships would come from a British colonial barrister in Calcutta with the impolitic name of Sir William « Oriental » Jones. In a 1786 lecture, Jones, who was also the founder of the Asiatic Society of Calcutta, made the argument that the classical languages — Sanskrit, Greek, Latin — had all emerged from a common lineage. Furthermore, Jones reasoned, there is evidence to believe that « both the Gothic and the Celtic […] had the same origin with Sanskrit; and the old Persian might be added to the same family » — a claim that could both cement and ironize the imperial logics through which Jones lived. It was also a hypothesis that, with my tongue-only-partly-in-cheek, has the enviable status of being completely correct nearly 250 years after it was first ventured.

More celebrated were the indispensable contributions of the folklorists Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm. Their collection of German tales was, in part, a means of tracing the subtle changes in dialects and languages, and from both their field work and their archival research, they were able to ascertain certain « laws » about how languages evolve. What’s now known as Grimm’s Law, first formulated in 1822, explained how stopped consonants could alter over the generations, so that the « p » in Latin piscis became the « f » in the English fish; the « p » in the German pater the « f » in father, and so on. These sorts of observations would be the tool of later linguists, like August Schleicher in the nineteenth century and Julius Pokorny in the twentieth, who honed the methods of resuscitating Proto-Indo-European, of understanding how transmutation in sound didn’t necessitate a similar change in meaning. These codified rules, based entirely in the anatomy of the mouth and larynx, could predict how languages would develop into new ones.

Words and sounds could also be retrofitted backwards. Philology flowered as a humanistic science in the nineteenth century, when newly-developed methodologies made it possible to trace language backwards to Indo-European, and thence to a still-older original. The history of communication is a history of mush-mouthedness, of consonants softening and vowels elongating from parents to children, as generations move and shift across the continent, dialects hardening into languages, an improvisational dance of phonemes and physiology across the millennia. Shifts in how we speak happen all the time, in plain sight and plain sound; slightly different pronunciations transmitting within families and locales, becoming briefly « standard, » but nonetheless always involved in a continual, mercurial flux.

The term « Indo-European » was introduced in 1813 by Sir Thomas Young (best-known for his work on optics). The prefix « proto » was added nearly a century later, in 1905, by the linguist W.C. Gunnerson. By the 1870s, as the linguist Guy Deutscher has explained in The Unfolding of Language: An Evolutionary Tour of Mankind’s Greatest Invention (2006), « linguists already had a number of remarkable discoveries under their belt, » due to the « deep understanding of how consonants in different Indo-European languages corresponded to each other. » In a manner analogous to the eighteenth-century Swedish botanist Carl Linnaeus, who taxonomized plants and animals (classifications invaluable to Charles Darwin a century later), so too does the branching tree of language evolution place a tongue like Dutch in the category of Low Franconian, then Weser-Rhine Germanic, then West Germanic, Germanic, and finally Indo-European. A language isn’t a plant, of course, but such categorizations speak to the nineteenth-century fascination with taxonomy and evolutionary thinking, whereby a language could be thought of as a species. (Indo-European is by far the largest « family » of languages, followed by Sino-Tibetan, Niger-Congo, Afro-Asiatic, Austronesian, Dravidian, and hundreds more, many endangered and even more extinct.)

Deutscher compared it to the manner in which an astronomer examining unusual orbits can use Newton’s laws of gravity to predict the existence of a heretofore undiscovered planet. A prime example is the Swiss linguist Ferdinand de Saussure, most famous today for his pioneering work in structuralism and semiotics, who in 1878 predicted the existence of a class of phonemes called « laryngeals, » a throat-guttural sound extinct in all Indo-European languages. (After his death, translators substantiated that such a sound existed in ancient Hittite.) Successes like this confirmed in the minds of linguists that what they were engaged in was not just a humanistic pursuit, but a scientific one as well.

Dirty limerick

By The Editors

«Write a dirty limerick in Proto-Indo-European. » Give that prompt to a large language model, for instance Claude, and it will hazard an « approximation » (after reminding you that « PIE reconstruction is scholarly speculation »):

h₁est wīrós h₁ék ̂ wōs megʰh₂lós

só h₁éǵʰom peku dheh₁t solós

gʷéneh₂ h₁ént speḱt

« tód h₁est h₁rēǵt! »

nú wīrós h₁est bʰuHtós kabalós

This limerick, the AI reports, « uses reconstructed PIE roots like *wīrós (man), *h₁ék ̂ wōs (horse), *gʷéneh₂ (woman), and plays with livestock / fertility imagery that would have been familiar to PIE speakers. » The AI’s English translation reveals a pretty generic attempt:

There was a man with a great horse,

He put his livestock alone in the house,

The woman saw (it),

« That is erect! »

Now the man is a swollen stallion.

It makes a kind of sense to ask a large language model to spit out some doggerel verse in a hypothetical language. Proto-Indo-European (a retrospective fantasy, a triumph of humanism) is mined by artificial intelligence (a prospective fantasy, a danger to humanism), and the result is a joke that no one would really get.

Ask for a dirty limerick in, say, Sanskrit (member of the Indo-European language family), and you will get one —

asti kaścid vīro mahāṅgaḥ yasya

liṅgaṃ sadā dīrgham aṅgaḥ

strī tam ālokya

« kim etat bhokya? »

sa vīraḥ kāmī mahāraṅgaḥ

— with the Devanāgarī script, too:

अस्ति कश्चिद्वीरो महाङ्गः यस्य

लिङ्गं सदा दीर्घम् अङ्गः

स्त्री तम् आलोक्य

« किम् एतत् भोक्य? »

स वीरः कामी महारङ्गः

The AI’s translation is: « There is a certain hero with great limbs, Whose liṅga is always a long member, A woman, seeing him, ‘What is this to be enjoyed?’ That hero is a lustful great-passion man. »

We could go on like this, for instance in Esperanto:

Estis viro kun granda organo

Kiu ĉiam staris kiel bano

Virino diris « Ho! »

« Kio estas tio? »

« Mia kara aminduma plano! »

The AI translates that one as:

There was a man with a large organ

Which always stood like a mast

A woman said « Oh! »

« What is that thing? »

« My dear love-making plan! »

It then explains — prudishly — that this limerick « maintains the cheeky humor typical of limericks while keeping the language family-friendly enough for Esperanto’s international community spirit. » Noted.

Return to the family-unfriendliness of Proto-Indo-European — this time giving the AI the constraint that the limerick must make use of reconstructed PIE root for « proto », which (it dutifully reports) is « *per- », a preverb meaning « forward/through » — and it will dip its bucket into the same well:

h₁est wīrós per h₁óynos bʰérōn

só perd péku̯ ns h₁ésti dhérōn

gʷéneh₂ per spék ̂ t

« per-tód h₁rēǵt! »

nú per-bʰuHtós h₁ésti kérōn

[There was a man carrying forward one thing,

He was holding livestock through/forward,

The woman saw through (it),

« Forward-that is erect! »

Now he is per-swollen, carrying horn.]

Maybe the algorithmic gravitation to livestock is inevitable. The folklorist G. Legman’s classic and exhausting anthology (The Limerick, 1969) has a chapter on « Zoophily », which includes a limerick that rhymes the name « Tony » with « fucking the pony » and (here you need the American pronunciation) « a yard-long bologna ». That chapter also furnishes a limerick in Latin involving an ape, which is better left untranslated:

Pine insulensis inevit

Rectum simioli quem scivit

Proles infrontata

Horrida glandata

Et semper violare cupivit

The limerick is an old form, but limericks were only called « Limericks » in the late nineteenth century, named after a city in Ireland that happened to feature in a recurring punch line. Legman’s introduction to The Limerick sought the origin of the form, reaching back to « proto-limericks of the Elizabethan age ». Ask an AI what the first-ever limerick was, and it will cobble / parrot / plagiarize an internet telephone-game genealogy that poses St. Thomas Aquinas as the form’s progenitor, specifically a poem in thirteenth-century Latin that happens to have a limerick-ish rhyme. Already in 1969, Legman had little patience for this origin story:

an accidental — or perhaps purposeful —

inner rhyme in a similar Latin hymn

attributed to St. Thomas Aquinas

(Thanksgiving after Mass) has led eager

searchers […] to credit the Italian monk,

Aquinas, with the creation of the English

limerick. Again, to say the least, an error.

The promise of Indo-European and Proto-Indo-European is the suggestion of a shared culture: we are united by that serpent-slaying forebear variously called Trito, Indra, Hercules or St. George — yet it’s also been used to justify the rankest of imagined racial differences. « The problem of Indo-European origins », as Anthony put it, « was politicized from the beginning ». Many philological discoveries were purposefully twisted, so that language became a substitute for race, not least because speakers of Hungarian, Finnish, Estonian and Turkish were excluded from the Indo-European family. Nineteenth-century Germans, fascinated by connections between their language and the sophistications of Sanskrit, appropriated « Aryan » for themselves, a word that applied to a supposed language before it was applied to a supposed « race » (and a word that echoes from « Iran » to « Erin », the Old Irish name for the Emerald Isle). Nazi pseudo-historians refashioned the light-skinned « Aryans » who had gradually migrated into Dravidian India some three thousand years ago into ancestors of its imagined Reich, and likewise refashioned that story of ancient migration into a story of invasion, conquest and lebensraum.

Even contemporary scholars who agree that Proto-Indo-European originated in the Black Sea steppe often have widely divergent interpretations of the same evidence. In 1987, the British archaeologist Colin Renfrew’s Archaeology and Language pondered « the puzzle of Indo-European origins ». It wasn’t only Nazis, after all, who had linked an imagined « Indo-European » people to the « warlike, chariot-riding Indo-Aryans » featured in the Sanskrit Rig Veda. Contesting a British archaeologist of an earlier generation, Sir Mortimer Wheeler, who had assumed an Indo-European « invasion » of India, Renfrew argued that the speakers of an Indo-European tongue had migrated slowly and peacefully westward: « There is nothing » in the Rig Veda, he wrote, « that to me implies an invasion ». In 1974, the Lithuanian anthropologist Marija Gimbutas, in The Goddesses and Gods of Old Europe: Myths and Cult Images, had claimed that the Proto-Indo-Europeans were a « patriarchal, stratified, pastoral, mobile, and war-oriented » people who violently supplanted a pre-existing matriarchal and pacifistic Neolithic culture in Europe.

Such debates — never conducted in an ideological void — can suggest alternatives to how we organize ourselves today — or at least can upset the teleological perspective that sees our own culture as inevitable. « We are projects of collective self-creation », write David Graeber and David Wengrow in The Dawn of Everything: A New History of Humanity (2021), asking « how we came to be trapped in such tight conceptual shackles that we can no longer even imagine the possibility of reinventing ourselves. » They answer this question with an array of egalitarian societies, excavated possibilities to stir our imagining.

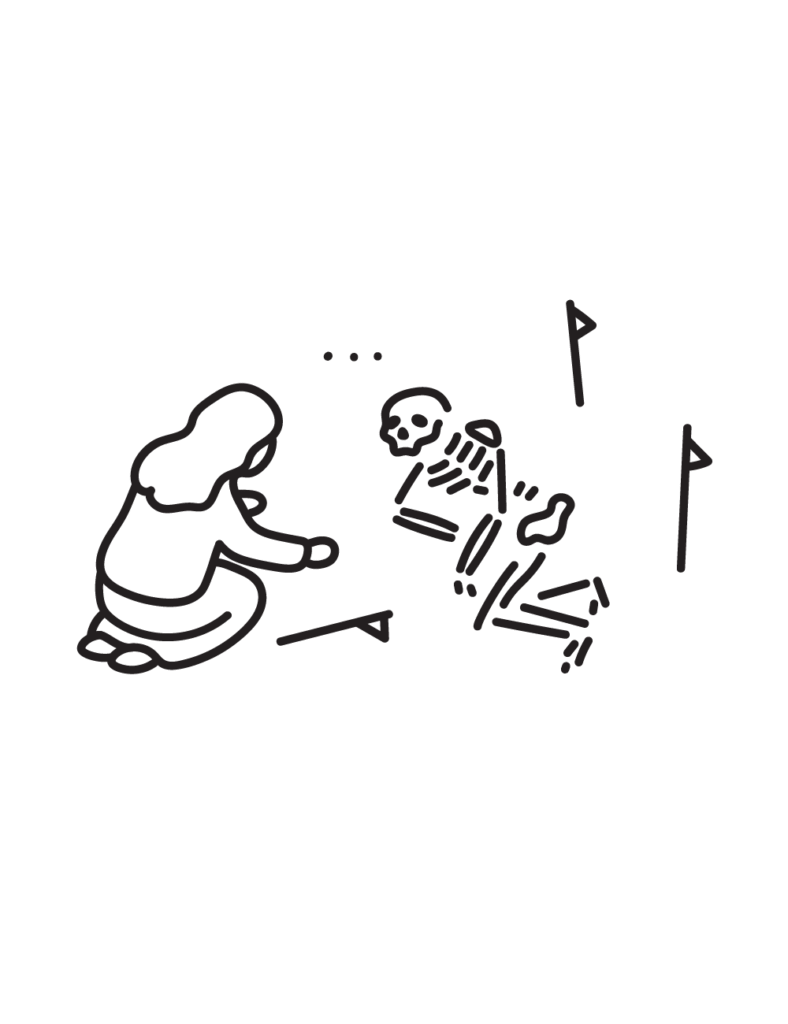

Today, the scholarly consensus seems to be that the first speakers of Proto-Indo-European were the Bronze Age people known as the Yamnaya. At the historical juncture when blacksmiths learned to add tin to copper so as to produce bronze, the Yamnaya had grazed their sheep and cattle across the Caspian Steppe. Here was where they espied the machinations of their deity Dyeus — the same who aided Trito — as storms gathered on the horizon.

Burying their dead along with distinctive, geometrically patterned ceramics, in pits carved from high-mounded kurgans that overlooked the flatness of the plain, the Yamnaya traveled on simple two- and four-wheeled carts with immobile axles, and possibly on horseback, through what is today a war-torn Ukraine. For a nomadic people whose survival depended on understanding the sunshine and rain, the dirt and the water, Dyeus’ position as a god who dwells upward was crucial because he could see so far and so widely. Some of the Yamnaya would travel eastward, eventually settling in the lands near the Indus, and the name Dyeus would shift over time until he would be called the near-cognate Dyaus, the sky deity in the Hindu Rig Veda, the « father […] the one who nourishes all beings. » Another remnant of the Yamnaya moved towards the west, settling along the wine-dark Mediterranean Sea. As they made their way towards the Peloponnese, their lazy tongues would fall over time towards the back of the palette so that the « d » in « Dyeus » would shift to the « z » in « Zeus », though the god’s purview would remain « the Kingdom of Heaven, » as Archilochus would describe it in a fragment, where he watched « men’s deeds, the crafty and the right. »

Echoes of Dyeus’ thunderbolts are heard whenever a prayer is offered in French to Dieu, in Spanish to Dios, in Italian to Dio. In five millennia, the god of the steppe nomads has conquered the world, while the scholarship that has ascertained this surprising fact has inflected different formations of European identity. As Laura Spinney writes in her new history, Proto: How One Ancient Language Went Global, that hidden genesis tongue is a « fibre stretched taut between » languages as various as Pushto and Manx, Breton and Sicilian. Spinney’s illuminating narrative defaults to a positivist focus on contemporary scientists, occluding the cultural implications of their work, and its humanist foundations. Yet her lyricism about a language across the epochs that « thrums in all of us who speak Indo-European, though we may not be aware of it » indicates a more poetic sensibility, in which Proto-Indo-European means more than phonemes and genes.

The Yamnaya have meant different things depending on who extolled them, from a model of European unity to the racist conjectures of Nazi pseudo-historians who grafted « Aryan » origins onto their own Teutonic lands. Today’s science has this small population first telling their stories of heroes slaying serpents on the banks of the Black Sea, the germinating seed of almost five hundred extant languages spoken by half of the world’s population. In the West it would seem that in a very real linguistic sense we are all Yamnaya. The « European » Eden turns out to have been Crimea.

The Yamnaya dusted their dead in red ocher and covered them in cowry shells for burial. Their sites were first discovered in 1930, by Soviet engineers constructing the Azovstal metalworks in Mariupol. More recently, the kurgan which entombed the Yamnaya dead would be obliterated in the Russian assault.