Or, paradise plundered

ORIGINS

One of my earliest memories is foraging with my grandmother. She lived in the north of Bulgaria, between the Balkan Mountains and the Danube, and in summer she would take me on all-day outings to the woods above her town. We’d pick Nettle for fritters, Pine-cones for cough syrup, Lime blossom for hay fever tea, and Valerian for nerves. We’d gorge on berries and return home with bags full of goodies. I was a nature-deprived city child, and this was a balm.

Thirty years later when I moved from city to country, it all came back to me. Never mind it was Scotland and not Bulgaria, here were the same familiar characters: Nettle, Valerian, Pine, Lime blossom and Blueberry. I entered the woods as if no time had passed and I became my grandmother, with a forager’s bag and needles in my hair, chewing dandelion heads with glee. But I was very alone. Foraging as a seasonal rite is forgotten in Scotland and only the odd herbalist or gourmet cook can be found crouching in the undergrowth. Industrial culture has severed the bond between people and plants. Instead of visiting the woods, people visit the supermarket. A fog of forgetting covers the land. Only once, picking wild garlic, did I meet another forager — she’d grown up on an Australian orchard. We became friends. Plants bring people together.

If you know what you are looking for, you find edible and healing plants everywhere. The digestive Dandelion grows on your doorstep, the soothing Calendula pops up in the cracks of pavements, Raspberry leaf is good for colds and uterine cramp and Blueberry has now become a superfood. But when I looked at the contents of my medicinal tinctures and the kitchen cupboard, I saw that not one of them originated anywhere near me. The blueberries in the supermarket were from Peru. Big berries, a commercial hybrid that doesn’t get crushed in the trans-Atlantic containers but neither does it have any taste.

You’re reading this essay for free. With a membership, you can read the full magazine, and you get access to our fabulous Library.

Here’s our offer: 3 months unlimited digital access + 1 print edition for € 38,00 € 19,00

You’ll get Issue Eleven in print as your first magazine, right to your mailbox.

Blaeberries grow abundantly in the hills where I live. But you have to pick them yourself. And so with every other plant. This is how my yearning to be among plant people took me back to Bulgaria.

DOGWOOD

Dogwood is one of three villages along a ribbon-road that clings to the low terraces of the western Rhodope. From up here you see the broad Mesta Valley like an antique theatre awaiting the next act. This is where the bed of the Mesta River is at its widest. To the east begin the Rhodope Mountains, a massif the size of a small country. To the west are the Pirin Mountains, a range with a hundred glacial lakes. Warm Aegean currents come in from the south and make the climate mild and montane — ideal for highland plants, animals and people. It is all villages here, villages in the hills and in the plains, and just one large town people call simply the City. From up here you see the City like a burst necklace in a chalice. Nearby — the ruins of Nikopolis ad Mestum, a Roman town inhabited for centuries until invading tribes sacked it and squatted in it, then it was abandoned until the Ottoman invaders recycled it into a medieval town that became today’s City. The Mesta basin in south-west Bulgaria is untouched by heavy industry and the air is so good that you stand on a chardak veranda in one of the three ribbon villages and drink it like a potion. Dogwood trees thrive here and their Cornelian cherries are tart and sweet like medicine.

« You’ve come to the cleanest place, » said Rocky the Enchanter, chewing some burdock root. « We’ve been reduced an awful lot but you can still find mysterious things here. »

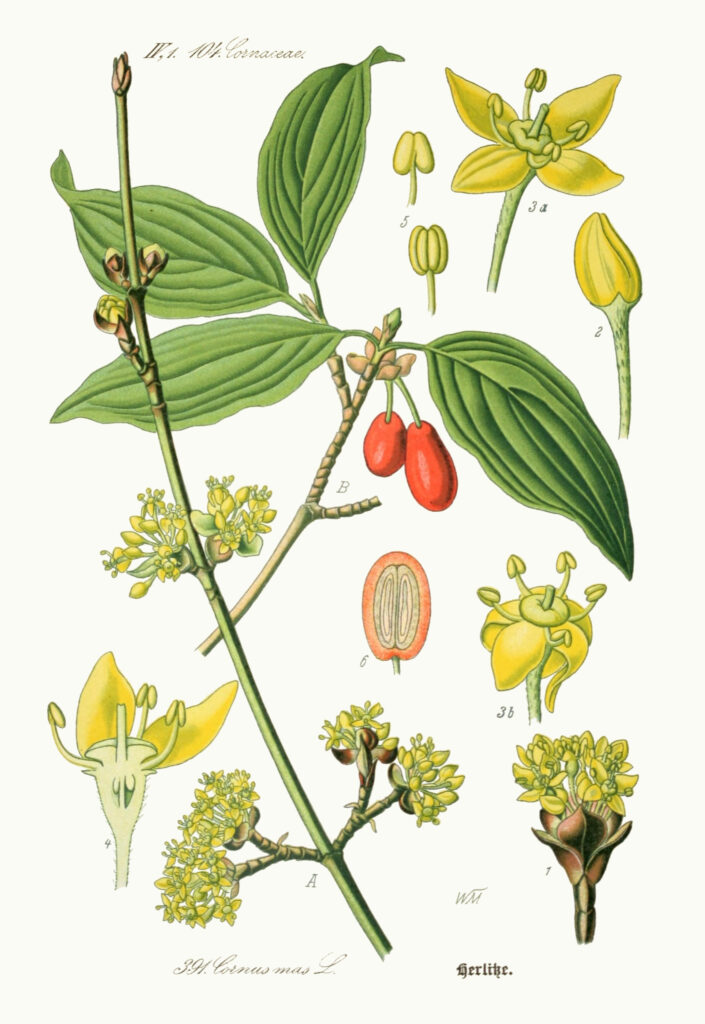

Cornelian cherry, Cornus mas

Cornelian cherry, or Dogwood, is the first tree to flower and the last to bear fruit in the Mesta valley. It has a long Mediterranean history and Theophrastus in the 3rd century BC wrote that it buds « before the zephyr blows ». Zephyr is the warm Aegean wind. Another Mesta local told me that in the potion Circe gave to Ulysses’ men to turn them into pigs, there was Cornelian. More to the point, it is good for diarrhea.

When he says we, he means plants and people. Rocky and his wife Nafié are plant gurus. Along the Mesta basin, every village has its expert foragers and dealers in berries, mushrooms, and herbs. Plant knowledge goes millennia back. Once, plant sellers were itinerant and criss-crossed the Balkans with sackfuls of mysterious things. Now it’s a more sedentary affair but there is still movement. Plant gathering and dealing as a way of life has survived in the Mesta basin because industrialisation came late and its ravages are not total. But they are bad enough. The plant-person bond is on the brink. Young people emigrate.

« Write it all down, » Rocky instructed me. « Coz in a hundred years’ time, you and I won’t be here to tell the world of these marvellous things. »

And he handed me a small pack of shredded Burdock root to chew. That’s how you get to know a plant, in the flesh, he liked to say. Burdock root smells and tastes of carob but when you boil it, the fragrance is tobaccoey and the tea is astringent and sweet, and makes you hungry. Rocky summarises: « Burdock is for when you’re depleted. » You can even rinse your depleted hair with burdock tea and it’ll get strong.

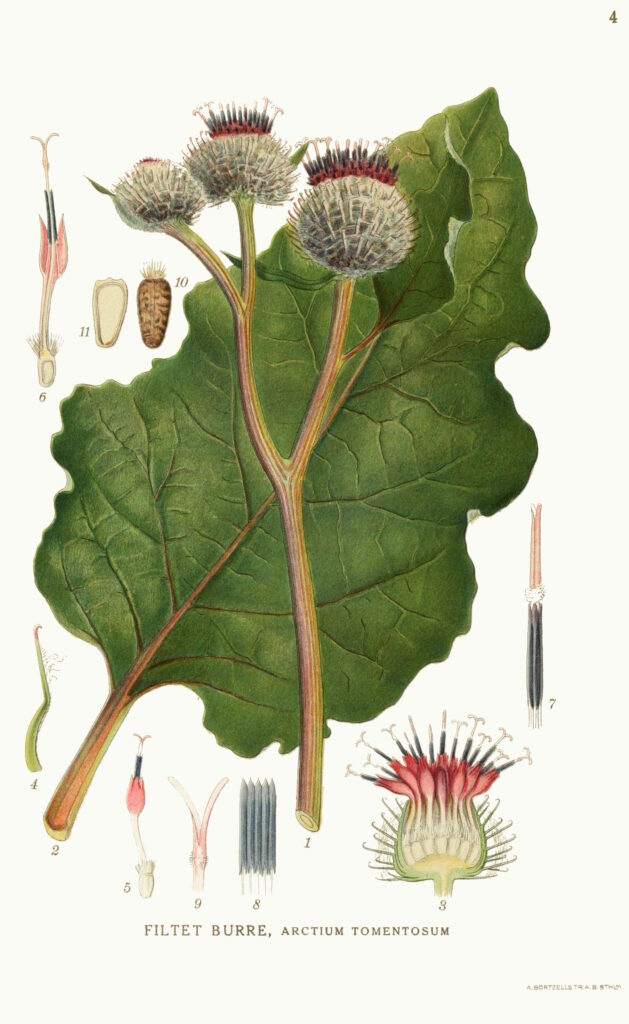

Burdock, Arctium tomentosum

Burdock is a liver-tonic like Dandelion. In Bulgarian rural communities, the roots were infused in rakia and that drink was taken to « cleanse the blood ». By the same logic, in springtime people ate snails whole, because the snails had munched burdock leaves. In Scotland an old pagan rite is called Burry Man. A man volunteered to parade for a day on the second Friday of August, dressed in a prickly costume made of burdock burrs. Like the Wicker Man, this scapegoat was meant to catch the evil spirits on his burrs.

You only see the top part of the plant but the root has all the concentrated qualities of it.

« Aye, herbs never sleep, » Rocky munched on. « There is no dead herb. In winter, you dig up the roots of the winter herbs, like Burdock and Dandelion. »

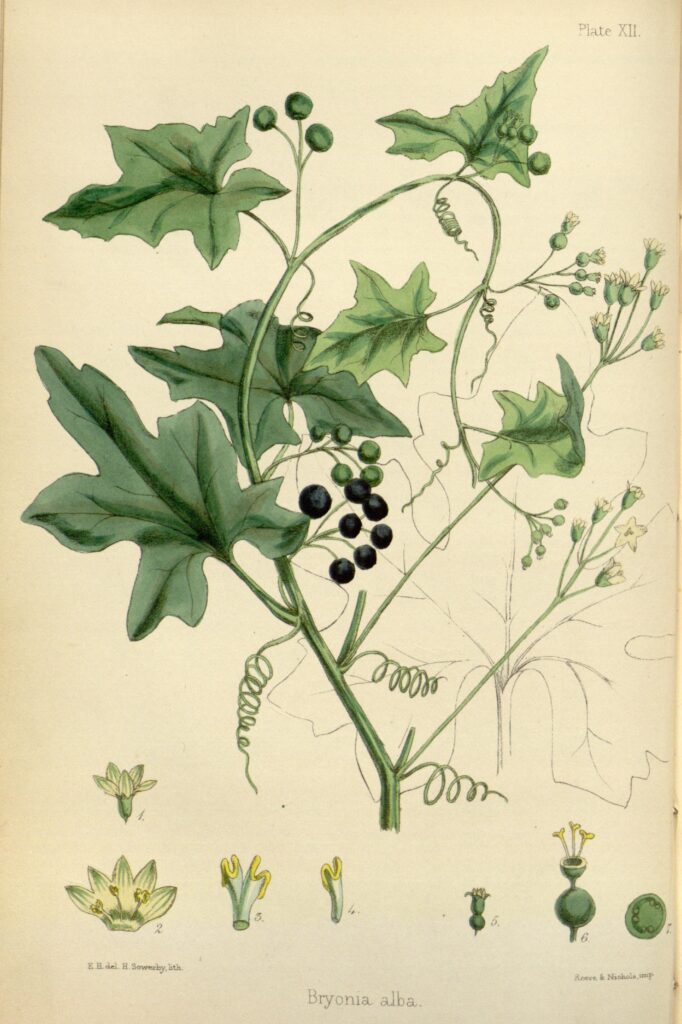

Staggering amounts of herbal roots are sold abroad, like white Bryony.

« Also called wild pumpkin and crazy pumpkin because it’s psychotropic and mildly poisonous. But mostly it’s used for slipped disks and the like. You make a hot salve from it and it raises a terrific fever and draws the inflammation from your body. I slice it and dry it and apply it like that. »

White Bryony, Bryonia alba

Wild pumpkin, crazy pumpkin. From the cucumber family. Its tuber is alarmingly large and grows arms and legs to resemble a homunculus. Digging it up takes work. Medicinally it purges everything from the body — inflammation, toxins, waste. Its laxative effect is known to be spectacular, and Rocky confirmed this with a story too graphic to share.

A German client bought over a hundred kilos of Bryony root. A hundred kilos! Roots can be heavy.

« And in Germany they don’t have it growing wild anymore. Many things are disappearing from the face of the earth. Humanity has got off the train, my friend. And is heading nowhere. »

White Bryony has a humanoid shape, like the legendary Mandrake which, pulled out of the ground without apology, is known to scream with a human voice. These are known as « man plants ».

« We don’t have Mandrake. But we still have a few mysterious plants. For example, the Belladonna. She grows very tall. There’s lots of it in a beech reserve but you need a guide to take you there. You lie under the Belladonna and she whispers you to sleep. That’s how you get to know her. »

Belladonna or Deadly Nightshade

Belladonna, deadly nightshade; wild tobacco; старо биле (staro bilé, old herb), and лудо биле (ludo bilé, crazy herb) in Bulgarian ethnobotany. In rural communities a dried belladonna leaf was placed in the crib to stop babies from crying. The leaves calm you down if you smoke them, and if the berries don’t kill you, in the words of early 20th century Bulgarian ethnobotanist Ananie Yavashov, they’ll give you « blue lips, dilated pupils, fever and thirst » and make you « smile stupidly and become drowsy. » The dilated pupils is why belladonna drops are still used in pharmaceutical drops. And guess which plant Juliet took to feign her death in Romeo and Juliet? Today Belladonna is used by medical herbalists to treat extreme anxiety and ADHD. In the Balkans, Belladonna and other magical plants are traditionally picked in the direction of the east for good, and the west for bad.

And he offered me some dried Belladonna leaves which you can smoke like a joint and sleep « like a little lamb ». The great English polymath Nicholas Culpeper described the Deadly Nightshade as « of a cold nature; in some it causes sleep, in others madness, and shortly after, death. » But, as the Swiss alchemist Paracelsus said: poison or medicine, it all depends on the dose.

I was staying one village downhill, and came up to see them every day. You smelled Rocky and Nafié’s house at the corner before you saw its veranda piled high with crates like a vegetal shrine. It’s a humousy smell, of mushrooms and roots just pulled from the ground. Rocky and Nafié blinked in the bright morning sun as they came out of their dark house for another busy day. Because summer herbs are a lot of work and it was August.

Nafié stacked crates full of a green leaf with a silver underside, shaped like a —

COLTSFOOT

She smiled at my identification. I had been learning some plant basics in Scotland, and now various vegetal names and shapes were coming back to me in Bulgarian.

« For chest congestion and gut problems, » Rocky confirmed.

That’s why it is called Tussilago in Latin, and in the north of Europe miners smoked it for their damaged lungs. Ancient authors recommended burning it and inhaling the smoke through a reed straw, while sipping warm red wine.

Coltsfoot, Tussilago farfara

The humble Coltsfoot is a living apothecary. It is not just good for your airways but for everything else in your chest — for example your heart. It slows down the pulse and regulates blood pressure. You can also use its leaves in the wild to bandage a wound, drain a boil, or dry them and use them as tinder to start a fire. Tip: always dry the leaves in a shady place.

« Do you hear the Coltsfoot? » We leaned over a crate and listened to the silvery-green leaf breathe, sigh, and rearrange itself in the crates, still getting used to being cut from the forest floor.

« Plants have a language. You have to learn it if you wanna talk to them. Now give us a hand on the scales, will you! »

This was my second day with them and I knew that my kind of help wasn’t needed, it was just them being welcoming. Because I like people who are interested in plants, Rocky liked to say. He was the talker, while Nafié padded around in friendly silence. She wore the blue mantle of Pomak women in this region that you can wear either buttoned up like a factory worker, or unbuttoned over your clothes with the ends fluttering in the breeze, which gives you the look of a highland fairie queen. The Pomaks are Bulgarian Muslims, and Dogwood, whose real name is Dryanovo, is a Pomak village. The Pomaks who traditionally live in Highland areas, are renowned for their pastoral knowledge. They are among the last true Highlanders of Europe. But behind the stoic faces of these women there is trauma. During Communism, Muslim minorities were periodically targeted by the state with hate campaigns. The Pomaks were forcibly stripped of their Arabic-Turkish names, stripped of their traditional dress, their graveyards desecrated with bulldozers, the minarets of old mosques broken. The villages of Mesta resisted. The result: army occupation that cut them off from the world. Many were beaten, some were shot and killed. Others ended up in labour camps. This heroic episode remains in the annals of Bulgarian Communism as the only instance of civil resistance to state terror. Despite the pogrom, Pomak culture survived.

You’re reading this essay for free. With a membership, you can read the full magazine, and you get access to our fabulous Library.

Here’s our offer: 3 months unlimited digital access + 1 print edition for € 38,00 € 19,00

You’ll get Issue Eleven in print as your first magazine, right to your mailbox.

Dogwood was a thriving village with a small mosque, a library, and another family of plant gurus — but there was no overt competition. They had different clients, established over time, and in this trade you are never short of clients. For urban people, the world of edible and medicinal plants is out of view, but it sustains everyone from behind the scenes, even if you don’t know it. The most used drug, Aspirin, derives its pain-killing components from the Willow, and its name is an homage to the fragrant-flowered Spirea, commonly called Meadowsweet.

« If you’re out in nature without Aspirin and get a toothache, chew some Willow leaves, » Rocky advised. « And Meadowsweet is for tummy aches. »

We weighed the crates on a standing scale. The Coltsfoot was dusty from vegetal spores. It was delivered yesterday by three guys in a van. They foraged in a sub-alpine area an hour’s drive uphill, along broken roads and river rapids, past a disused Communist-era army barracks. In those uplands are gathered the wild plants and mushrooms of summer and autumn. The gatherers are locals, mostly Roma and whoever is left in these villages and can’t find a better-paid job. The three Gypsy guys were skinny and sunburnt, and gruff but they smiled when they saw my notebook: here’s someone interested in plants! We grew up in the forest picking stuff, said one, Whatever’s going. Snails, primrose, berries. We’re used to it.

Up and down this broken road, making no money. In Western Europe, harvesters and agricultural labourers like these usually come from eastern countries. In Britain they are called unskilled workers. But the recognition, collection and processing of plants, wild or cultivated, is a complex craft with a distinguished lineage. If you chew Hemlock instead of Cow parsley, you will die. The wrong mushroom can give you kidney failure. You must know that Juniper cones are not berries and take two years to ripen and must be picked individually instead of cutting off entire branches. That you don’t pull up a plant by the roots, unless it’s the root you want, and even then you must make sure that enough is left for next season. And a well-mixed, expertly prescribed herbal tincture can help you with any kind of ailment, something I learned from using herbal medicine.

The three guys delivered 69 kilos of Coltsfoot in sacks and were paid 35 lev (18 euros). It was the going rate. Instead of petrol for their van, they used old vegetable oil. Rocky and Nafié spread the Coltsfoot in shallow crates to breathe overnight, and now we weighed them and packed them in Rocky’s van, for his driver to take to a bigger dealer. The Coltsfoot would then travel to suppliers abroad. It would be blow-cleaned, dried and shredded in this area. But packed, labelled, priced, and sold far away. Next time I see it, it will be in a health-food store near me — like Napiers the Scottish Herbalists.

Coltsfoot grows on my doorstep in Scotland. But people don’t recognise it anymore.

« Fancy a little pack of this? » Rocky handed me a bag of ground red Chili. « Very sweet. »

I did fancy it.

Back in Scotland, I would open my cupboard and look at the ground chillies, bought in a whole food store. Country of origin: packed in the UK. Anonymous chillies, then.

Authentic Italian sundried tomatoes: produced in Italy from non-EU sundried tomatoes, and in small print: Bosnia.

Sundried courgettes, parsnips and onions: from Uzbekistan.

Linden leaves and flowers: from Bulgaria. Maybe my grandmother’s town.

Rose petals: from Pakistan.

Oregano: from France.

Dandelion root: from Poland.

And authentic Italian forest mushrooms: from Croatia.

All of these plants grow well in all European countries. But the global chain of supply prefers to bring plants to our cupboard that have traveled a long road and left a large environmental footprint. The money is made at the top of the chain, while the origins are over-harvested and the gatherers and gurus remain poor. Napiers’ dried Coltsfoot costs £54 per kilo — because it was not harvested in Scotland and because medicinal herbs are a luxury instead of a lifeway.

The driver arrived and the Coltsfoot was placed in his van and taken away. Rocky used to drive the produce himself but now he was almost blind. What happened to your eyes, Rocky?

« It’s a long story. Let me first tell you about — »

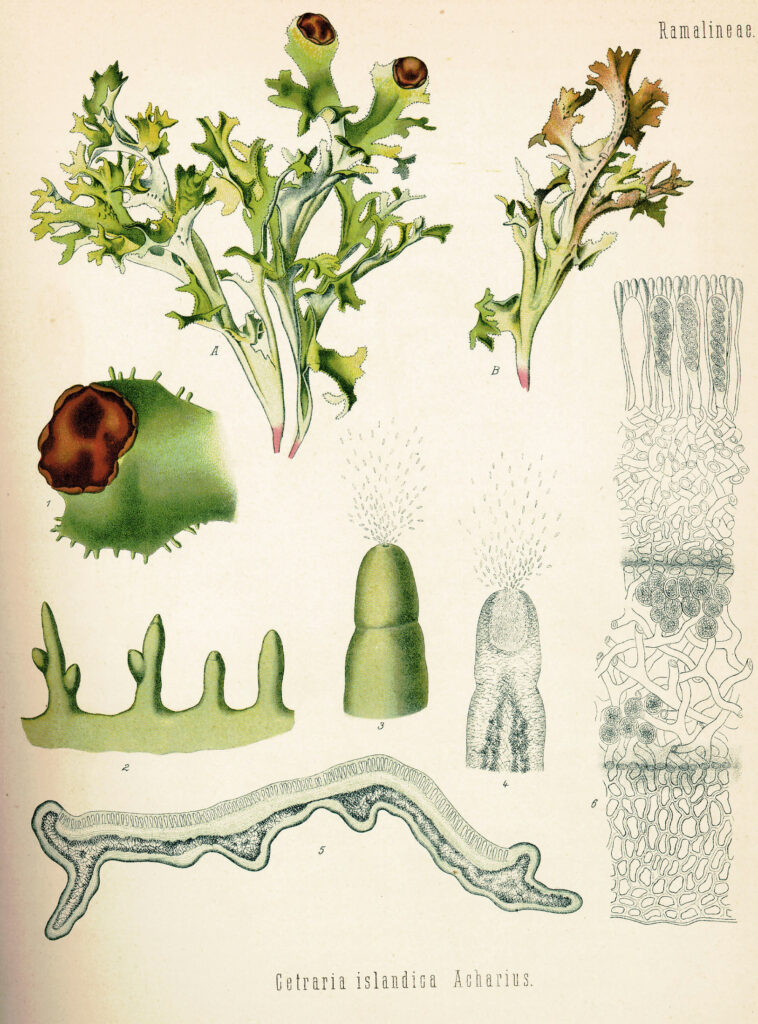

ICELANDIC MOSS

Rocky was nicknamed Enchanter after the little orange-red flower Avens whose Bulgarian folk name is the enchanter, Omainiche, because folk botany uses it to put people under a spell. And Rocky was enchanted by the plant world since childhood. He would go into the pine woods above Dogwood where bears roam, and return three days later with a dreamy look, leaves in his hair, and a bag of rare plants. After the fall of the Communist regime he rose to be supplier of the country’s largest herbal business. One day, high in the alpine pastures, he made a big discovery: Icelandic moss. Nobody knew it could grow in the southern Balkans! Icelandic moss is prized for its immune-boosting components and its healing effect on the lungs and throat. Before antibiotics, northern Europeans took it for tuberculosis.

« It’s a lichen that looks like a moss, » Rocky specified. « A pure plant. »

Icelandic moss, Cetraria islandica

Lichens like Icelandic moss are traditionally eaten by humans and grazing animals. For example, the lichen that reindeer like is called Reindeer moss. For centuries lichens have sustained northern European creatures with their high mineral content. A stranded Arctic explorer survived eleven days on boiled lichens. To get rid of the bitterness, you boil the lichens in water with a bit of wood ash, but I admit I haven’t tried this yet.

He made money from it, for a while. But others followed him into the secret home of the Icelandic moss, I mean lichen — and took it from him.

« It was a blow but we recovered. You know, there are over three hundred types of lichen in our mountains. The easiest to spot is Old Man’s Beard, a natural antibiotic. It likes Pine and Oak, and most other trees. Look for the white thread inside it. »

It looks exactly like an old man’s beard and oddly enough, it’s taken for hair and scalp problems. This is called the Doctrine of Signatures — when the plant resembles the thing it heals because of the energetic correspondence between them. Some researchers have called this « morphic resonance ». Mysterious things indeed.

And the stakes of this trade are as high as its roots are deep.

Out of view, large quantities of plants are sold to the pharmaceutical industry, the health-and-wellness industry, and the cosmetic industry. Rocky told me that Bulgaria has 742 medicinal herbs. Then there are the gourmet plants, of which berries and mushrooms are collected in the wild and the rest are cultivated. Bulgaria is one of Europe’s major exporters of edible and medicinal plants, and the largest exporter of Lavender and Paprika. Of all the plants harvested wild or cultivated, eighty per cent go abroad wholesale — that is, unpackaged. The main destinations are Germany, Austria, Spain, Britain, and Greece. The quality of our produce is due to the rich soil and the climate, Rocky stressed. In short, healthy ecosystems. But ecosystems are suffering. Forest felling is the main destroyer, because when a single mature tree is cut, a whole community disappears with it.

« Each tree you cut changes the microclimate. What grows in its place? Juniper and bramble. Nothing else. »

Monoculture: both the result of damaged ecosystems and the destroyer of ecosystems. It is because of mono crops, pesticides, and industrial farming that plants are becoming extinct from our planet at the rate of one per day. Sometimes two or three per day. This means that the 742 healing plants living in this corner of our continent can disappear in just two years. This fact causes me to feel pain in many places. That’s why I came here. To see what’s left.

The biggest blow to Rocky and Nafié came around the time when their business was really taking off. And it was to do with mushrooms. Mushroom, in local parlance. Is there mushroom? Mushroom is singular but infinite, like god. With their special sight, professional mushroomers see the underground cities called mycelium that prop up the world and communicate with forests. You recognise a mushroomer if you pass them on a forest road because they have a rucksack, a small motorbike, and look blind and deaf to all but the mushroom hiding in the undergrowth. A mushroomer once told me: If the overground cities are destroyed, the underground city will be here still. The city of mycelium. I hope he is right. I hope mushrooms inherit the world.

In the post-Communist years of feral privatization, an era known as the Transition, armed racketeers went round these abundant villages and took people’s plant businesses, or anything else they had, at gun point. These were the embryonic businessmen of the future oligarchy that fused with politics. A plant man in this village was placed on a wood-mill and threatened to be chopped up like a log unless he signed over his business to the racketeers. One evening, Rocky had mushroom to the tune of 7000 euro in the house. Ready to be loaded in the morning and delivered to a dealer in the City. That was a lot of money for a small business. But the racketeers came in the night and took his stock and his clients. The shock of it gave him diabetes and high blood pressure and over time, he lost his eyesight. He had to feel his way around, and when he peered at you, he also sniffed the air to work out who had entered the house. His sense of smell is his best asset, said Nafié in passing, deadpan.

« You know how you get to know a plant once it’s picked? » Rocky scanned me with milky blue eyes. « You leave it on the table, leave the room and enter the room again. And there it is. It fills the room. »

The smell is the voice of the plant.

Wild basil, Clinopodium vulgare

Originally brought in from Asia and Africa, Basil is the quintessential Mediterranean herb but only grows in European gardens. In the Balkans, no ritual is complete without basil and to this day, a sprig of basil is used in Orthodox churches for sprinkling « anointed » water. The reason is not magical but practical: basil is antibacterial, cleansing and uplifting. Basil clears the mind, makes you hungry and interested, and helps with urinary woes. Wild basil is not really basil but a member of the much tougher, wild-growing mint family. Yet it has some of the properties of basil, plus some of its own — it is a broad-spectrum regenerative plant and a tonic for gynaecological problems. Look out for its small pink florets in late summer pretty much anywhere in Europe.

« Now what’s this? » Rocky tested me with a crate full of some pink-floreted plant I couldn’t quite recognise and he couldn’t quite see. We sniffed it. Hints of mint.

« Wild basil. A regenerative plant. »

Never seen so much of it. In fact, never seen any of it. What was it for?

« Ladies’ » problems, indigestion, prostate and kidneys, and skin problems. But it’s more than that. It’s got very strong anti-oxidants. I tell you, one day it’ll be a cancer cure!

Bring it on! There is a saying in Bulgarian folk medicine: За всяка болка — билка. (« For every pain — a plant. »)

Then we ate blueberries from a big bowl, picked in the woods this morning by a neighbour. They were so sweet, I thought Nafié had sprinkled them with sugar.

Blueberry, Vaccinium myrtillus

The European blueberry, also called bilberry and blaeberry, is small and packed with flavour and goodness. The original Danish name bollebar means dark grain. This resilient berry can survive anywhere as long as there is clean air and drained soil. It seems to be adapting well to climate change through chemical self-regulation. It contains an astonishing amount of beneficial acids and tanins which make it a potent traditional remedy that clarifies the skin and the eyes, strengthens the urinary tract, and acts as an all around anti-oxidant in the body. The leaves are bitter and slightly toxic but you can dry them and make an immune boosting tea in winter. It was in the Middle Ages that the European blueberry was recognized as medicinal food, first in the writings of the mother of European phytomedicine Hildegard of Bingen.

BLUEBERRY

The heat was sapping and we sat on a shady bench outside their door to munch fresh goat’s cheese. Many Pomaks in the Mesta region make a living in summer by setting up road-stalls and selling delicious and too-cheap home-made cheeses and yogurts, and all the bounty of the forest. We ate the cheese with tomatoes, and sprinkled it with Oregano and Summer savoury which grows wild here. And crisps.

« Not as good as our own crisps, remember those, my boy? » Rocky turned to the large guy who’d joined us in the shade: Rocky’s nephew.

Twenty years ago the nephew was his apprentice and hoped-for heir. They tried all sorts of things, with success: home-made crisps from local potatoes packed with flavour which they sold to shops and supermarkets; cured animal skins; organic sundried vegetables. But the problem was — all the locals were emigrating or going across the border to Greece to work seasonally for 25 euro a day, which was more than was offered here. Now they do the same but in western Europe. Come summer-autumn, the young people of these villages travel west and only old people are left.

« It pains me to see it, » said Rocky. And there is no plant for that pain.

His nephew too had emigrated to Finland where he worked as a truck driver. He missed Dogwood, he missed dealing in living things, the excitement of it, the way of life.

« In twenty years we’ll retire here with a Finnish pension, » he said, and this is what happened in many of these half-empty villages. People spent a lifetime working abroad, built a dream house in their homeland, returned with a good pension and promptly died.

« That’s why I like people who want to learn about plants, » Rocky turned to me with his unseeing eyes.

Nafié smiled stoically. They had no successors. The long lineage of the plant guru would die with them. It was a quiet tragedy.

The village was silent. A van drove past, two guys waved and grinned. One of them was Rocky’s driver. They were returning from a morning’s harvest of blueberries in the uplands. But Rocky and Nafié didn’t deal in berries anymore and the two guys were going to another dealer in the Valley.

I’m off for blueberry. Blueberry, like mushroom, reigns supreme. It is everywhere. I bought myself a harvesting comb — you gently run it through the low berry bush, and the berries separate and fall into your bucket, no leaves. Back in the days of serious wild harvests — that was during Communism — the whole village would pack up and depart for the uplands. Families would spend the summer there, camping and picking. Barbecues, songs by the fire.

Star pickers could harvest 50 kilos of blueberry in a day. They are sticky and perishable and must be processed at once — so the star pickers would stay up all night in special processing buildings, separating the berries from any leaves. And in the morning, after a 24-hour shift, they would fall asleep with the sticky juice on their hands, just as forest stags crossed the rivers.

« Now hunters shoot the stags, » Nafié said with sadness.

They shot them back then too, but environmental crime was limited to the political elite. Now it is almost limitless.

« And there is less of everything, » Nafié added. « Less eagles, less deer, less forest. »

The ecological damage is lasting. The entir agro-economy was owned, controlled, and monetized by the Communist state and some plants were picked to near-extinction. Ancient Beech and Oak forests were cut and the priceless timber sold cheaply to the Soviet Union. Most of the forest that is now here is not native. And the felling continues, but without replanting.

« Tree-felling is my biggest sorrow. The Blueberry likes clean, well-aired places, » Rocky said. « When you cut a forest, the air changes, the soil changes, invasive species arrive, the shade disappears, and the berry goes somewhere else. »

Blueberry, mountain Cranberry, Raspberry and the small forest Strawberry — these aromatic soft fruits can be bought at market stalls in the region. But if you go to a supermarket, you’ll find those blueberries from Peru. Rocky groaned with the pain of it.

« We don’t have people. The irony is, all our people that know about growing plants go to pick strawberries in the greenhouses of Scotland and to plant Christmas trees in German farms. Instead of here. Without the Roma we’d be lost. » And here came the first mushroom delivery of the day. It always started around this time, 4 o’clock.

MUSHROOM

It was a Roma family. They unloaded bags and crates of fungi from their rickety van. They lined up the produce outside and soon the street was covered in fungi. Nafié sat at a desk inside, writing down the details in a ledger and handing out cash to the foragers. Rocky sniffed the produce and felt it, chatting all the while.

A young woman brought a 2 kilo cep.

« First quality, » said Nafié and paid her and the woman’s wilted face lit up.

The rate for first quality was 8 lev (4 euro) per kilo and 3 lev for second quality. First quality meant younger ones. You could tell from the colour and texture of their undersides. Chanterelles were bought for 4 lev (2 euro) per kilo. You could make decent money but the footwork was huge. I met mushroomers who made 200 lev a day, but they went to places where only bears roam. And sometimes attack. If you meet Mama bear in the woods, don’t look her in the eye coz that makes her mad, a mushroomer advised me.

A boy came in with a single Cep. Eighty grams, first quality. Nafié handed him the coins and the boy grumbled. His face was prematurely aged. She soothed him and he left.

« It’s hard with the young Roma. They’re often iliterate and can’t count. You need compassion. »

A man brought out crates of Ceps. His face was etched with hardship.

« Is that soggy? » Rocky picked up a Cep. It was a thing: some pickers sprayed their mushrooms with water to make them heavier. But Rocky was wrong this time. It’s just that the Ceps had sweated.

« The old eyes let me down, mate, » he apologized to the man who didn’t take offence.

« Ach we’re growing old, mate, » he replied. « The system kills us. »

This family were from the Roma ’hood in the Valley. It was a shanty town, men drank heavily and the oldest person was a sixty-year-old woman. The tragedy of the Gypsies is the tragedy of all once-free people in Europe. Forcibly settled in the early years of Communism — just like the pastoral nomads — they never took to the sedentary way of life. They fell between the cracks. Instead of travelers’ camps — ghettoes. The plight of the Gypsies and other Travelers is a stark reminder, if we need one, that Europe has no place for freely moving people, animals, or people with animals. Only tourists with the right passports.

I suddenly recognized the etched man. I’d seen him up in the alpine area a few days before. I’d driven up there with a local guide who showed me the abandoned Communist-era agri-complexes where he had worked as head shepherd. All the buildings were derelict, still with furniture and even some broken public signs from the 1980s: IN THE FIGHT AGAINST NATURE, WE SHALL BE VICTORIOUS.

This is where the summer pickers bivouacked, hung up their laundry washed in the river, and gathered mushrooms. And up there I saw something I can’t forget.

The bivouackers sold their harvest to a dealer from the Valley who drove up each day at 4 o’clock. He paid them the same rate as Rocky. They handed over their bags and he filled the empty crates in his van. But during the delivery, two women clashed over a bag of Chanterelles that fetched 20 lev. Each claimed it as hers. It got heated. One woman picked up a stake. The other — an axe. They lifted their weapons and screamed wildly, like banshees. We all froze. Then the etched man stepped in and pulled the women apart, risking an axe in the head.

Back at Rocky and Nafie’s, the last mushroom delivery was processed. Rocky’s driver arrived, we loaded the crates, and I joined them for the long scenic drive to the next dealer who lived in a Pomak village upstream the Mesta. Rocky’s driver did this virtually for free. Like all the younger Mestans, he worked abroad seasonally. Pulling asparagus in Germany. Coz we love our country but it’s not possible to make an honest living in it. The system kills us. When he came back home, he lounged about, picking berries for small change, but only coz blueberry and mushroom are an itch. You’ve got to scratch it. Nothing to do with money. The bigger dealers were a gruff family who regarded me, an outsider, with suspicion. What if I was spying for the competition? They made a bigger cut than Rocky. Rocky asked me to write down in a notebook the weight and price of every crate, as they weighed them again to make sure he wasn’t cheating. Tomorrow, these mushrooms would be cleaned, cut and dried in local premises by low-paid women, then sold to an Italian dealer in the City. He would have them despatched to Italy wholesale, where they would be labelled authentic Italian Porcini, and in small print: EU agriculture. I would next see them in a deli in Scotland or Italy, 12 euro for 100 grams, with a pretty ribbon. And if I hadn’t climbed to the source of it, I could be excused for not knowing that two women from the Mesta Valley nearly killed each other over a sack of Chanterelles.

By the time we drove back to Dogwood, it was dark. Nafié waited in the lit-up doorway of the house with a tired smile. Tomorrow they would do this all over again.

Galen the ancient physician wrote about a man who speaks the language of plants so well that he turns himself into a plant at will. Rocky is that man. If I stayed and became his apprentice, I too would become half-woman half-plant. Already my sense of self had shifted. From human-centric to biophilic. Being human is only part of being.

Night fell in the Valley. I closed my eyes and saw roots and mycelia stretching, hissing and discussing the future with 742 voices under the ground, while the world above slept. There are no dead plants. In the early morning, you saw that the Oregano was flowering purple, that the Coltsfoot flashed its silvery underside at you and the Bryony whispered with its deathberries.

And if you come from the Roma ’hood and are young and broke, it is in the early morning that you come out of your shack and hit the streets in search of work or old scrap for recycling. Then you trudge up the mountain road to where new mushroom has hopefully popped up overnight, or whatever gets you a few pennies. And keeps you close to the plundered paradise that is your homeland.

You’re reading this essay for free. With a membership, you can read the full magazine, and you get access to our fabulous Library.

Here’s our offer: 3 months unlimited digital access + 1 print edition for € 38,00 € 19,00

You’ll get Issue Eleven in print as your first magazine, right to your mailbox.