A new Mediterranean epic for the age of despair

Otherworlds: Mediterranean Lessons on Escaping History

Federico Campagna

(Bloomsbury Academic, 2025)

What is the Mediterranean world? Most of us, I’d guess, would think of a place on a map. We might define the Mediterranean by its borders, those of the twenty-two countries that currently have sea access. Our sense of Mediterranean history might default to the cartographic, too, tracing the older empires and territories that once existed around its shores.

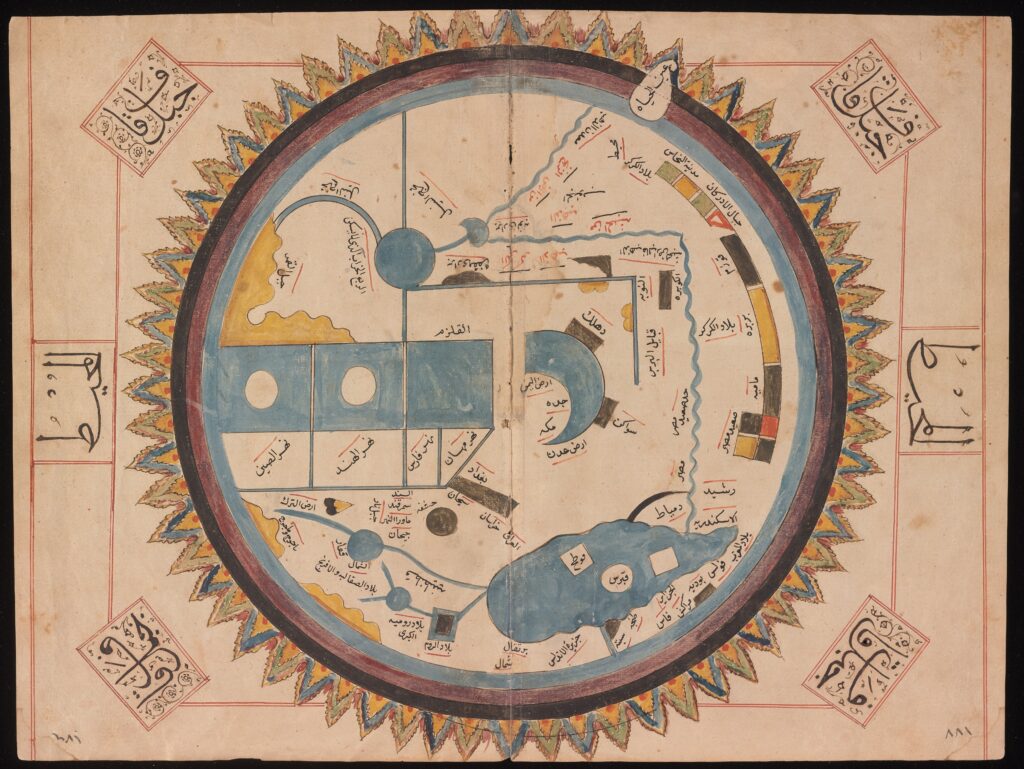

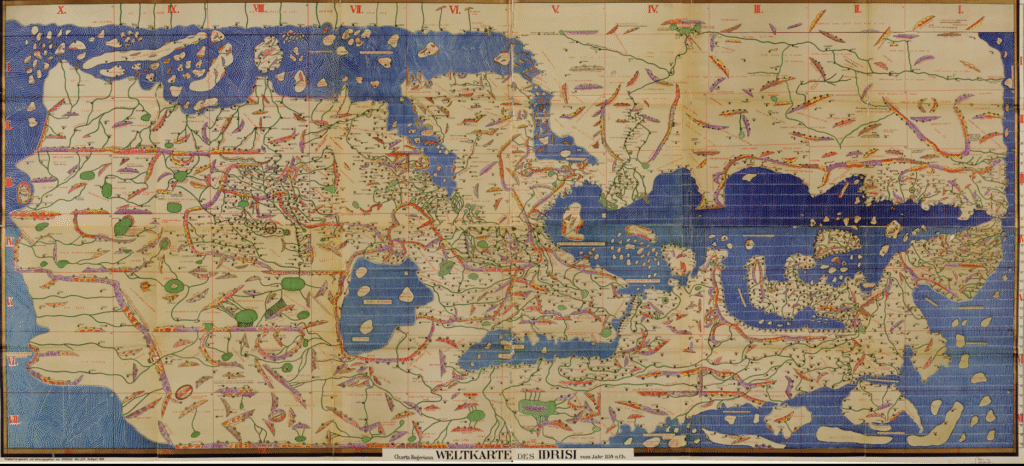

Maps can orient and disorient. The maps on our phones default to what’s known as the « Web Mercator projection », aka the « World Geodetic System 1984 ». One could, if one wanted, turn it upside down with one’s fingers so that it’s more like the Tabula Rogeriana of 1154, created by the Arab geographer Muhammad al-Idrisi at the request of King Roger of Sicily, his cosmopolitan Norman patron. North was on the bottom, south on top, Mecca at its center. « Europe » was relegated to peripheral status. Back in 2011, amid the simultaneous fevers of the Arab Spring and Occupy movements, I stumbled across another such map by the French cartographer Sabine Réthoré, which riffed on al-Idrisi’s proposal to striking effect: rotate the sea by ninety degrees, erase national boundaries, and our eyes will scan a Mediterranean defined not by geopolitical fractures but by … something else.

Mediterranean time has more than four dimensions. I remember as a student when I first read the historian Fernand Braudel’s masterpiece, The Mediterranean and the Mediterranean World in the Age of Philip II (1972). Philip II, the book’s eponymous Spanish monarch, is barely a character; Braudel’s real subject was time itself — historical, cultural, even geological. How continental shifts and climate fluctuations forced population movement over millennia, how weather and wind shaped the rise and fall of entire civilizations. Where his contemporaries had hurried to archive and document historical events according to preconceived periodizations (« the Age of Philip II » was in that sense an ironic title), Braudel’s approach was multi- or non-chronological, process-driven yet suspicious of straightforward determinism. If Mediterranean time sprawled, so did Mediterranean space, extending beyond the sea into areas of the Sahara Desert, and to the Black Sea. The Mediterranean, untethered from place, emerged as a world of cultural contradiction, encounter and adventure.

Braudel was writing in the 1970s; his method pushed beyond Cold War dualisms. It also excavated a deep historical precedent to « globalization », then seemingly new — and seemingly unstoppable. Today is another era. The space of the Mediterranean is changing rapidly, with new kinds of wars, ecological devastation, mass migration, increasing poverty. Of course, it never wasn’t changing — that was Braudel’s premise, too, and his histories conveyed a powerful ongoingness, equipping his readers to see the present as ongoing, and therefore promising. The overtone of promise surely strikes differently now, in an era consumed with a sense of its own ending.

You’re reading this essay for free. With a membership, you can read the full magazine, and you get access to our fabulous Library.

Here’s our offer: 3 months unlimited digital access + 1 print edition for € 38,00 € 19,00

You’ll get Issue Eleven in print as your first magazine, right to your mailbox.

Enter Federico Campagna, the Italian philosopher who, throughout his career, has been traversing the fringes of Mediterranean thought to recover and recuperate lost knowledge — in lost knowledge, after all, lie challenges to present hegemonies. From his early anarchist writings, in books like The Last Night (2013), to the mystic meditations in Prophetic Culture (2021), he has charted esoteric paths through history, with an eye on modern existence. His new and most ambitious work, Otherworlds: Mediterranean Lessons On Escaping History, is a philosophical epic for an age of despair — or, if you like, an adventure story, no less adventurous for being abstruse.

Part philosophy, part history, part literary criticism, Otherworlds gravitates, first, to the origins of storytelling itself. Creation myths, for Campagna, are not folklore but living cosmology. The Mesopotamian peoples imagined themselves as clay — slave-like machines that the gods invented only to relieve themselves of work. The Greeks considered life a « curse », and developed tragic art as a tool to endure the bleak truth that, for humans, the best fate would be not to be born at all. Then comes the Hebrew Bible’s account of the fall from innocent bliss to the world of hard labor and exile. For Campagna, the creation that these creation myths narrate is, in effect, a foundational brutality and suffering: life as a « labour camp » from which there is no mortal escape. These form, so to speak, the sea-floor of the Mediterranean cosmos.

In order to survive amidst this bleak existence, the Mediterranean people established two distinct strategies: hopelessness or salvation. Some embraced hopelessness as the best way to approach the absurd condition of human life. This path, which Campagna traces to pagan thinking, entailed an embrace of hedonism — a life in which love, art, and pleasure are sufficient to keep despair at bay, at least for a while. « If the human trajectory was a downward spiral, to every person remained, at least, the possibility of falling beautifully. »

The other path was to reject hopelessness and throw oneself wholeheartedly into stories of redemption, albeit in a life beyond. Campagna traces this tendency back to Egypt, where worshippers of Osiris refused to see death as a definitive end and instead proposed that the human mortal condition was part of a transformation, in which souls would unite, ultimately, with an essence both universal and eternal. This myth would develop into the Christian afterlife, in which the pure and/or faithful can achieve deliverance from sin.

For Campagna, both poles are equally valid or invalid modes of navigating existence. Together they frame the Mediterranean mind. Having established that binary (epistemologically shaky though it may be), Campagna’s narrative will arrive at, and in a way champion, cases in which it breaks down. Hence his attention to the « hermetic » cult of Hermes Trismegistus, which emerged in the third century, a fusion of the Greek god Hermes and the Egyptian Thoth, whose followers proposed that humans are already divine: they cannot really die but only flit in and out of the world in different forms. Or Manicheanism, the school of thought that detected, beneath humdrum human existence, a truer, albeit unseen, mystic realm of good battling evil. Or Gnosticism, some current of which heretically proposed that the God of the Bible was, in fact, a malicious demon who organized the murder of Jesus, humanity’s true savior, in order to subjugate the world’s population. Otherworlds is a scholarly book, and its account of Gnosticism is appropriately arcane, working through the fragmented codices of the Nag Hammadi Library — the Gnostic Gospels discovered in Egypt in 1945 — in the course of recovering, and celebrating, the movement’s « anarchic harmony of differences ».

Reading Otherworlds means moving, with clarity or confusion, between two planes of existence. On the one hand is the world of history, society and economics — in essence a series of catastrophes, one after the other. On the other — above or beneath that dismal plane — is the world of metaphysics, philosophy, literature and art, through and from which, the author claims, the Mediterranean has escaped itself (and we can, too).

Campagna is a migrant philosopher. Born in Northern Italy to Sicilian parents, he has lived and worked in London for many years. Migration is likewise a key frame — the key frame — of this book. The opening chapter of Otherworlds recounts childhood summers spent in the small village of Prizzi, in Sicily, where he’d observe itinerant workers experiencing time along « parallel lines » — between the « suspended instant » of their lost homeland and « the rhythm of work in a distant land ». Campagna’s own family packed their car boot with passata and olive oil, mementos to help them survive winter in the cold North. Later in the book, Campagna recalls a childhood memory of eating a giant candied puppet, a pupo di zucchero, which Sicilians believe preserves the souls of the dead. Munching on its sugared almonds on a November evening in Milan stirred both dreams of fantastical encounters and fears of ancestral ghosts.

These anecdotes, poetic and seemingly decorative, are a useful clue to the book. Otherworlds is populated with migrants of every kind; nomad scribes, geographers, poets, singers, precarious composers. Many of the protagonists are refugees. In one memorable passage, the author zooms in on the Roman poet Rutilius Namatianus, who fled the « barbarian » invasions in the fifth century. Not content with a bloodless account of that ransacking, Campagna turns novelistic, having the poet survey the « remains of burnt houses scattered across the fields […] the fresh graves of those who had been caught by the fury of the Visigoth troops. » Rome, Campagna writes, was « moribund, its few remaining inhabitants clustered around the stones of the old buildings, like mussels on a rock. » Similar descriptions — or imaginations, or projections — recur throughout the book, from the account of Muslims fleeing the Christian « reconquest » of medieval Andalusia and Jewish exiles escaping the Spanish Inquisition, to Italian coastal communities cowering in fear of Ottoman pirate raids. The present becomes powerfully legible in those terms: a particularly bracing chapter jumps into our century, the author imagining himself as an anonymous asylum seeker in an undisclosed part of the Mediterranean, listening to « the ominous quiet of the migrant detention center and the echo of traffic » while planning an escape from the Frontex border police.

Migrants are the principal custodians of Mediterranean cosmology and, as such, its archetypal subjects. A migratory experience of space and time is, after all, different from a more static existence — more intense, more historically and philosophically interesting. Vulnerable to various violences and brutalities, migrants have therefore, even in the best of circumstances, been forced to play a more active and conscious role in building worlds to live in. For Campagna, Mediterranean migrants in particular have had to forge their path between the twin poles of hope and hopelessness, narrating stories to defy the constraints of history and imagine themselves free amidst beautiful escapist fantasy or via the utopian dream of refuge.

Otherworlds‘ meticulous emphasis on the centrality of migrant experience to all aspects of Mediterranean culture is one of the book’s great achievements. Campagna’s historical interpretations pointedly unroot subjects from present containers: rather than write of « Greek heroes » as if they were tied to that modern language and nation, he conveys generations of population movement. The taken-for-granted epithet of « Alexander the Great », for instance (the familiar label for Alexander III of Macedon), has its accumulated layers restored in Campagna’s thickening interpretation. Greek-speaking colonizers spread Alexander’s story as they settled across central Asia, incorporating elements of Buddhist folklore into the tale as they moved. Centuries later, in Persia, a land the real Alexander had devastated, migrants and artists including the poet Abu’l-Qâsem Ferdowsi Tusi began to re-write this past in fantastical terms. And so, a millennia after Alexander’s death, Ferdowsi and others reimagined the hero as all things to all men: a Greek-Aristotelian who was also « spiritually » Persian, who respected Zoroastrianism, and who paid respects to the Kaaba in Mecca. The real Alexander, a power hungry, ruthless tyrant, was forgotten. In literature, he was reborn as Sekandar, a mythological hero, « freed from history. »

One of the more unexpected migrant protagonists in Otherworlds is the Austrian novelist Joseph Roth. Born in Brody in 1894 in Austro-Hungarian Galicia (now part of Ukraine), Roth becomes, for Campagna, a kind of honorary Mediterranean, all because his fictions preserved a certain cosmopolitan pluralism through the Habsburg Empire’s collapse. Roth was a melancholic man, tragically attached to the dying multi-lingual and multi-cultural world he saw slipping away. He spent his later years flitting from Austria to Paris and New York, drinking heavily and surveying history with a detached nostalgia. In his books, though — Radetzky March (1932) above all, an epic novel about a Slovenian family navigating the final years of Austro-Hungary over three generations — Roth created a romanticized, affectionate, tender fantasy of Habsburg society, removed from the real violence of history.

Why dedicate so much space of a « Mediterranean » book (with anarchist philosophical commitments) to a conservative Central European novelist? Well, why not? While Roth’s own wanderings were driven by the Nazi persecution of Eastern European Jewry, his experience of itinerancy connects him with Campagna’s Mediterranean migrants. His novels were a generosity: the gift of a literary reality in which other lost and untimely souls could learn to live, despite all odds, with dignity. Roth may not have understood himself to be working in a still-living tradition, « Mediterranean » or otherwise — but Campagna welcomes him into a borderless one, with generations of other existential exiles. In Otherworlds, Roth’s escapes are given a paradoxical new home.

From the sixteenth century forward, following the European colonization of the Americas, the Mediterranean would become what Braudel evocatively called a « provincial lake ». As Campagna notes, the tectonic effects for culture were devastating. As the world churned towards our modernity (teleology, technology, nationalism, capitalism, etc.), humans around the Mediterranean Sea, as elsewhere, would become more and more fixated on identity of particularly claustrophobic kinds. The Austrian and the Ottoman empires, for all their authoritarian hierarchy, contained multitudes of peoples — « nations but not nationalisms, » as the author puts it. The new world was starker. A Greek was a Greek. A Turk was a Turk. A Croatian, Croatian. Entire populations learnt to see their collective selves in flags and costumes — and, eventually, in brands. That is the « history » this book offers « lessons on escaping », lessons from a Mediterranean sea-turned-provincial-lake — no longer an economic vanguard, yet still alive with migrant flows and cultural syncretism.

To be sure, this is not a book that strategizes, or even expects, the Mediterranean to triumph over capitalism and nationalism. Campagna’s earlier books had a more pointed anarchist politics. While Otherworlds certainly lauds Mediterranean socialist movements, and excavates counter-hegemonic currents that flow beneath and beyond dominant power structures, its « escapes » are, by design, poetic or metaphysical — bespeaking, perhaps, a pessimism about present prospects for collective action to force historical change.

The book can instead be read as a catalog of isolated anomalies — of individuals and movements that have achieved a revolutionary break in « history », enduring or not, and others that found ways to articulate still-durable universals — or even the « universal » a vast abstraction that recurs throughout the book — as their own worlds broke around them. Among the book’s revolutionaries (for lack of a better term) is the Italian-born anarchist Cesare Camilieri, who in the nineteenth century converted to Islam, moved to Constantinople, changed his name to Hasan bin Abdullah and would have a hand in organizing the assassination of the Italian king Umberto I in 1900. Or Gabriele D’Annunzio, the decadent poet who formed a proto-fascist micro-state in Fiume in 1919 which, paradoxically, gave birth to one of the most unexpectedly progressive (and short-lived) constitutions of the age. What entrances Campagna about D’Annunzio’s messy experiment is the poet’s attempt to manifest a utopian society: universal suffrage, equality in the workplace, welfare for all, multilingual education, sexual freedom and, ultimately, the abolition of exploitative work. That the venture was doomed from the very offset is key to its appeal: « the collective effort, it seemed, was aimed at suspending the flow of time », Campagna observes. « Fiume could look no further than the instant of its present… the revolution could live only for as long as the imagination allowed. »

As for the book’s visionaries of the universal, Campagna’s point is that the Mediterranean — both a literal region and a metaphysical one — has been their incubator. Its system of differences shows us cracks in an age obsessed with fixed identity. Long-dead figures thus re-emerge with lessons: Hypatia, the fifth-century pagan Neoplatonist philosopher, mathematician and astronomer who lived in Alexandria and opposed superstition and religious dogma; Ibn Rushd, the twelfth-century Muslim-Andalusian philosopher who, amidst inter-dynastic warring, posited the existence of a universal ideal mind held in common by all Muslims, Christians and Jews; Isaac Luria, a sixteenth-century rabbi who preached that beyond earthly war there exists a divine, cosmic scheme, in which all are united, and that through prayer, ritual and study all of us can help to repair the world.

Campagna offers a particularly affectionate portrait of Pico della Mirandola, the Italian Renaissance polymath whose biography, and work, crystallize many of the book’s themes. Born near Modena in 1463, and based in Florence for most of his life, Pico embarked on a diligent study of world religions. His Oration on the Dignity of Man (1486) is a monument of humanist syncretism, building on Greek classics, Muslim and Zoroastrian philosophy, and especially the Jewish mystical tradition, all to propose a new, gloriously apocalyptic Christian kabbalah, in which the divine was everywhere. It fits Campagna’s account that Pico’s writings would ruffle feathers in the Vatican. How could they not? Pico gathered every Mediterranean particular — « the combined heritage of the whole Mediterranean » — and tried to assemble the pieces into a universal whole, every description of which (Campagna’s included) will slip through the fingers:

Moving systematically, he sketched the blueprint for a universal philosophy, where the different dimensions of reality appeared simultaneously through the angles developed by thinkers of any era or provenance. Since reality is infinitely varied, only the concerted effort of all human minds can hope to obtain even a minimal image of its true structure. Rationalism and mysticism must proceed hand in hand, since for every aspect that can be observed and analyzed, infinitely more exists beyond the grasp of mind and language. The prime example of such complexity is right before our eyes: the human, in all its limits, is a perfect case of how much more there is to reality than what meets the eye.

Reading this account of Pico’s heretical cosmopolitanism, I found myself, for a moment, possessed by the golden light of revelation. So this was what Campagna’s book was all about! Yes, the Mediterranean has become a site of historical pessimism: its foundationally bleak cosmology alive in the present’s endless struggle. Yet it is also, beneath and above « history », a place where catastrophe is answered. Reading about Pico, and some of the migrants and mystics who preceded and followed him, I found myself curiously light of heart, even while being trapped in history. There were comedowns, too, the whiplash of pure pessimism.

« Escaping history » is not escapism. Walking down a rainy grey street in Florence, where I live, past austere palazzi, and piazzas that Pico himself must have known, I found myself oppressed by the crowds, the adverts, the modern city’s dismal merchandise. Cold and damp, I ducked into the Palazzo Strozzi which is currently hosting an exhibition about the medieval Dominican friar and artist Fra Angelico. I’d already seen the show once, but as I surveyed it anew, with Campagna’s words still resonating in my mind, the paintings took on a different form. I paused transfixed before the monumental San Marco Altarpiece (1443), which was dismantled in the seventeenth century and which the curators have successfully reconstructed thanks to loans from museums in Washington, Munich, Dublin and Paris. As the sirens echoed down the street outside, I stood in silence before the newly reassembled panels, mesmerized by the details of palm trees, camels, fine silks, ornate carpets, miracles and visions. Angelico’s cartoon-like architecture, so starkly framed against twilight skies, suddenly transformed: it emerged as a direct portal into the celestial realm, a sanctuary from the catastrophe we call history. I began to appreciate fully the generosity of Otherworlds‘ invitation to dedicate more time to our own Mediterranean protagonists. In that moment I noticed a detail that had escaped me. The Christ-child is seated, imperiously, with a globe in his left hand, and there it was: a glimmering Mediterranean, speckled with cosmic dust, shining brightly at the center of the world.

You’re reading this essay for free. With a membership, you can read the full magazine, and you get access to our fabulous Library.

Here’s our offer: 3 months unlimited digital access + 1 print edition for € 38,00 € 19,00

You’ll get Issue Eleven in print as your first magazine, right to your mailbox.