Read in:

Подолати минуле: глобальна історія України (Overcoming the Past: The Global History of Ukraine)

Ярослав Грицак (Yaroslav Hrytsak)

Київ: Портал, 2021

A history told twice, from inside and out

« First I wanted to become a rock star, » said Ukrainian historian Yaroslav Hrytsak in an interview.

He did, in a way. Being an academic historian, professor at Lviv National University and Ukrainian Catholic University (also in Lviv), someone who spends his time in archives, writes books, someone who taught at Harvard and Columbia, Hrytsak is also columnist for the illustrated weekly magazine NV and a lecturer welcomed beyond the academic world.

« That doesn’t make you a rock-star, » one may say. « Just another Harari ». But that’s the thing about Ukraine: if you happen to be a Ukrainian historian, writer, or poet, or even an academic philosopher, you must become a rock star. In some cases literally: before the pandemic, Serhiy Zhadan, likely the best-known Ukrainian writer outside of Ukraine, was on tour roughly 300 days a year: either as a front man with his band or doing poetry readings. Performing with a band on stage — be it hip-hop, rock, punk or electronic music, or just recitation with jazz accompaniment — has been rather a norm for a Ukrainian writer for the last three decades. More: the response, even to an unaccompanied poetry reading, may remind you of a rock concert: the turnout, their age, how the crowd behaves. It’s a shocking experience for an outsider. But back in the 1990s almost everyone was poor, the book industry was scarce, and to write in Ukrainian, not Russian, meant being an underdog from day one. It wasn’t enough to be good, you had to be cool to get attention.

Yamandu Roos:

Odessa, 2010

YAMANDÚ ROOS

25 September 2010, Odessa

Yaroslav Hrytsak doesn’t sing, but you can listen to his twenty-two podcasts on the history of popular music from the 1960s to 1980s. He connects it all: tracing progressive rock back to its inspirations — to Bach and Beethoven, and to Marianne Faithfull’s song « Plaisir d’amour », the original of which, by the way, was written a couple of years before French Revolution, and the aristocrats who heard the premier would be guillotined soon, and Marianne Faithfull, by the way, has aristocratic ancestors herself, and one of them, by the way, was the Galician writer Leopold von Sacher-Masoch, globally known for Venus in Furs but less known as an admirer of Rusyns (Galician Ukrainians); and on and on. Hrytsak started his academic career researching worker movements in late-19th-century Galicia, then an eastern province of the Austro-Hungarian empire. He wrote a 600-page book about the Ukrainian intellectual Ivan Franko and the political and intellectual atmosphere of that era, and he also gives lectures about The Beatles.

His newest book, Подолання минулого: глобальна історія України (Overcoming the Past: The Global History of Ukraine), appeared last November and quotes The Beatles in the introduction, as well as Sting (« As Hegel wrote, and Sting sang, history will teach us nothing »). It explains the difference between 17th-century Ukrainian and Russian orthodoxy with carols (the Catholic origins of caroling meant no carols in Russia). It explains the difference between the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe with rock music (underground in the former, openly available in the latter), and between communist Poland and the other communist countries with The Rolling Stones (they performed in Warsaw and nowhere else).

The concept of the nation is Hrytsak’s main topic. A nation is not a good in itself, but the necessary « platform for modernization ». He has been saying this for many years. He has gathered, accordingly, a diverse collection of haters. The most obvious opponents are the ultra-nationalists, for whom he is a man of many sins: his writings on Ukrainian nationalist organizations of the 1930-40s are way too unflattering; he is too good to Poles, Jews, Russophones, Ukrainian socialists and social-democrats of the late 19th and 20th centuries; he promotes Western liberalism and has been welcomed by the unforgivably monied academic institutions in the West. But this litany doesn’t automatically make Hrytsak a sweetheart of the Left, Poles, Jews, Russophones, and Western academia. For some of them, his writings on Ukrainian nationalist organizations of 1930-40s are way too flattering, he says that Poles were not only heroes and that Jews were not only victims, he unapologetically criticizes the Soviet regime, and he promotes Western liberalism. You get the idea.

In the afterword to Overcoming the Past, Hrytsak admits that although he would prefer Ukraine to be a liberal democracy, he doesn’t consider himself a liberal. He rather follows the advice of philosopher Leszek Kolakowski, one of his intellectual gurus, and tries to be « a conservative liberal socialist ». This new book may add some more haters along with admirers.

I might as well note here that I began this essay before the Russian invasion of Ukraine; I am finishing it during that invasion. Hrytsak, meanwhile, has stated that February 24 marked the beginning of a « new era in Ukrainian history »: « We are not ‘Ukrainian people’ anymore » he wrote in a column for Ukrayinska Pravda, « We are the Ukrainian nation now. » The war, he says, calling a spade a spade, is « not Russia’s aggression against Ukraine, but the patriotic war of the Ukrainian nation with Russia. » The book aimed to overcome the past; perhaps the present has in turn overcome the book.

Or, after February 24, maybe the book takes on new poignancy. Hrytsak demonstrated that Ukraine was never an island; its history was always intertwined with the global, even in its deepest Soviet isolation. In 2022, likewise, Ukraine didn’t become an epicenter of world history all of a sudden. It’s truer to say that Ukraine became an epicenter again, only this time the world is watching.

Professional music producers know that to become a hit, a song must mix something familiar and something new. The same goes for popular history: a hit must consist of well-known facts and an unexpected interpretation and reshuffling of those facts.

While the 19th and 20th centuries have been Hrytsak’s main expertise, the new book shakes the usual narrative of Ukrainian history to the medieval core, beginning with the labels themselves: Ukrainian political history starts with the « Kyivan/Kievan Rus’ », the 9th-century state formed on the territory that is now the heartland of Ukraine. The term is widely used both in Ukraine and in Russia, but it is anachronistic: a state with that name never existed. « Rus’ » did, but no one called her « Kievan ». The awkward « Kievan Rus’ » is an invention by Russian historians in the 19th century. (The « Byzantine Empire », meanwhile, is an invention of the 16th century.) The greatness of the state that did exist is usually exaggerated both in Ukrainian and especially Russian history—Vladimir Putin is obsessed with the idea. (Hrytsak ties what he frames as Kieven Rus’’s intellectual backwardness to its adoption of Eastern over Western Christianity in the 10th century, when Kyiv King Volodymyr married Grand Princess Anna Porphyrogenita, the sister of Byzantine Emperors Basil II and Constantine VIII. Anyway.) Nor was Rus’’s transformation into Ukraine the fulfilling of some providential destiny, and nor, of course, does that destiny extend into the present. In fact, old Rus’ had to die so that Ukraine could be born. Or as Hrytsak says, Rus’ was to Ukraine what a caterpillar is to a butterfly: there is a connection, but this connection becomes irrelevant the moment one starts to fly instead of crawl. Cossacks, Ukraine’s official founding fathers (they’re in national anthem: « We, whose forebears, and ourselves, proud Cossacks are! »), weren’t even all ethnic Ukrainians, necessarily: they were a mix of different peoples, and at some point chose to become Ukrainians.

These and other notions won’t be entirely new to academic historians. A gap between the academic and the popular view of the past is not unique. What marks the Ukrainian case is that both the academic and the popular perspectives were under severe pressure and censorship more or less until 1991; some historical facts and interpretations were forbidden. It’s only natural that myths would emerge as overcompensation, to counter a loaded Russian narrative. Some Ukrainian myths might merely invert the Russian ones, replacing one « cradle of civilization » with another. Even quite credible Ukrainian literature and media often fall into the same toxic trap of claiming « greatness » for something as arbitrary as national history. Hrytsak’s goal, though, is less to debunk myths than to reveal history as a process. « My ideal is a history without names and dates, » he writes in the preface. He focuses on the twists of cause and effect that become clear when one observes the broader picture or the longer durée.

For those who follow Hrytsak as a columnist and a speaker, substantial parts of The Global History of Ukraine may sound familiar. (Full disclosure: Hrytsak contributed a lot of his energy and knowledge to the Nestor Group and Univ Group—independent groups of experts that met once a month on Saturdays to ponder strategic visions for Ukraine and for the city of Lviv, something between a 19th-century salon and a floating think tank—and your reviewer is also a member of both.) For many years Hrytsak has been working on a Ukrainian history for the British publisher Blackwell’s. That book he never wrote. The Global History of Ukraine is the one he finally did. With this in mind, it’s hard not to inwardly translate it to English and to imagine how a non-Ukrainian reader, especially from a distant country, would perceive it—especially now, when any history of Ukraine will be read as a preface to the war.

Then again, would they even pick it? Will it be translated? The Gates of Europe: A History of Ukraine (Basic Books, 2015) by Serhii Plokhiy of Harvard University may be the safer choice. If such a reader was interested only in the past—in the historical facts, be they « Ukrainian » or « global »—Hrytsak’s book might annoy them, because « Overcoming the Past » is not just a title, but a mission. The title is a literal translation of the German term Vergangenheitsbewältigung, the country’s policy to cope with the past after the Second World War, though Hrytsak’s is a very different kind of « overcoming ». His focus is not historical memory, exactly, nor the traumatic past, but historical narrative itself.

And yet a reader not particularly interested in Ukrainian history may be all the more fascinated by the Ukrainian story, and what Hrytsak secures for his country is a story line in the global tale. For example: the iconic images of Soviet tanks in Prague in 1968, crushing the Prague Spring, are easily recognizable, but few in the West, even among historians, know the name of Petro Shelest. Shelest, the first secretary of the Communist Party of Ukraine, was a vigorous promoter of the Soviet crackdown. A reader at this point may imagine him to be a Moscow loyalist, but Shelest had more complicated reasons to applaud the tanks. As a result of the Prague Spring, the Greek-Catholic Church was legalized in Czechoslovakia; it had been forbidden in the USSR since 1946 and severely persecuted in the Russian Empire before that. The faithful of the church, a mostly Ukrainian minority, were localized in the eastern region of Slovakia. Across the Czechoslovakian-Ukrainian border lived the Greek-Catholics of Western Ukraine, which was, along with the Baltics, one of the least Sovietized region in the USSR (as it was first annexed only in 1939, and then again in 1944). The region was also notoriously rebellious. Czechoslovak legalization might reanimate Western Ukraine’s surprisingly resilient underground movement. Shelest was managing the risks.

Hrytsak also shows the reverse: how supposedly « national » historical events would be impossible without developments elsewhere. For instance, 1492, a standard milestone in world history, becomes a milestone in Ukrainian, too. Two major events happened on opposite sides of the globe that year: Christopher Columbus stumbled upon America, and the Cossacks of the steppe frontier first appeared in the historical records. 1And in the Orthodox calendar, as fate would have it, the year 1492 was the year 7000, an apocalyptically round number. Hrytsak exploits the coincidence, narrating Ferdinand and Isabella’s Reconquista of the Iberian peninsula, and their subsequent sponsorship of Columbus’s voyage, alongside the Orthodox expectation of the end-times. (« That was the end. The end of the world created seven thousand years ago. ») Columbus’s plan for Ferdinand and Isabella was to find the new route to India, and fund their Reconquista of Jerusalem with his trophies. And there Ferdinand would wait for the Antichrist, and then for the Christ, because where else?

The idea of Ukraine—that is, the entity that isn’t merely the territory or its material resources; the thing that is somehow different from its neighbors; the work-in-progress that is Hrytsak’s protagonist and that will, over the centuries, articulate itself with Western tools—would emerge as the world became global. In the century that followed, Spaniards found vast deposits of silver in Potosi (now Bolivia), the mass import of which caused an increase of money supply, which in turn caused a jump in prices, first and foremost for food. The ensuing crisis in the western part of Europe benefited the elites of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth (the Rzeczpospolita, literally Res Publica), which had meanwhile absorbed the Ukrainian territories. The local barons who controlled those territories, now filthy rich, forced the colonization of the eastern frontier – the Ukrainian Wild East, if you wish – and enslaved peasants to maximize the output of grain. This spread of serfdom in the 16th and 17th centuries, Hrytsak notes, prepared the ground for the later division of Europe into « West » and « East »: Eastern Europe would become, in effect, an agrarian colony of the West, a periphery of the capitalist society that would arise on the Atlantic coasts. More immediately, that economic model, with its huge gap between the mighty magnats (barons) and their subjects, set the stage for the violent uprisings to come.

1648 is another milestone, another year of global coincidence and grand irony. The Peace of Westphalia ended the Thirty Years’ War; the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth had stayed out of it—had indeed enjoyed a decade of so-called « golden peace »—but turned into a bloody mess just as the war ended. By this time the Cossacks were a military estate that served the king of the Commonwealth, protecting its southern and eastern frontiers. Aware of their importance, and expecting the same rights and privileges as the gentry of the realm (the szlachta, their rivals), they revolted. The Cossack revolt of 1648 marked the beginning of the long end for the Rzeczpospolita. Seeking support for their uprising, Ukrainian Cossack elites, having proclaimed a new separate state, the Hetmanate, opted to become a protectorate of the Muscovite tsar. The Muscovites, in turn, would absorb them, and together they would transform the Russian backward state into a fast-expanding empire. But the protector/protectorate relationship was, to say the least, an unequal one, with much lost in translation. Cossacks understood it as a treaty with mutual obligations; Muscovites understood it as an eternal enlargement of the tsar’s realm. The Cossack Hetmanate had its own customs system and could make agreements with foreign states until the beginning of the 18th century, when the Russian tsar Peter I ripped that agency away. In 1781, Catherine II abolished the remnants of the system and fully absorbed the territory of Hetmanate into the Russian empire. The final blow to what was left of the bleeding Commonwealth, meanwhile, would come in 1795, with Poland-Lithuania partitioned between the Russian Empire, Austria, and Prussia.2

The outcome of the 1648 uprising for Ukraine still provokes heated debates far beyond academic circles. On the one hand, the scale of devastation, the economic and human losses, were so appalling that the subsequent thirty-year period is still called The Ruin. But on the other hand, an aspirational Ukrainian nationhood emerged, however haltingly, out of those Cossack wars and their complex aftermaths—a distinct Ukrainian political tradition, too. « The main national difference between Russia and Ukraine, » Hrytsak writes, « is not religion and not even a language, but the difference of political traditions. » Indeed the distinctions of language, religion, and identity are secondary, even red herrings. Ukrainian Cossacks were distinct from Russian Cossacks: the Cossacks in Russia as well (on the river Don, so the name is Donskie Cossacks) never became a nation, while the educated Cossacks elites in Ukraine were supported by organized burghers, with a network of schools and publishers, with autonomous institutions and the separation of powers. Partitioned yet strongly connected to the developments in Western Europe, the Ukrainian political tradition was insulated from the trajectory of Muscovite and Russian autocracy.

But the modern version of the Ukrainian political entity would need Western ideological boosters.

If modernization was a religion, Professor Hrytsak would be one of the first apostles. Back in the late 1980s, as a young Lviv professor, he was involved in new legal and semi-legal Ukrainian organizations, as well as in the underground milieu. As a member of Lviv’s Lion Society (a sort of fraternal or civic society, originally concerned with local history, that germinated into a more radical organization as the Soviet regime became more vulnerable), he named its newspaper, which later became one of the most important ventures in Ukrainian journalism: « Поступ / Postup » (« the progress » in Ukrainian). The paper’s slogan—« More sweat, less blood! »—was a quote from Ivan Franko, the protagonist of Hrytsak’s earlier histories. This motto reflected the worldview of the new generation of Western Ukrainian, anti-Soviet activists, journalists, and intellectuals, who would later take part in non-violent protests on Maidan in Kyiv, in 1990 and 2004, and launch political campaigns, media outlets, and non-governmental organizations.

As a child growing up in a Galician village near an old resort town, Hrytsak glimpsed some of what traditional country life used to be. His adolescence coincided with rapid Soviet modernization, which in the Ukrainian case was asymmetric: Ukraine was deliberately provincialized, for instance by a censorship regime that was harsher than in Russian metropoles like Moscow or Leningrad, that confined the Ukrainian language to the Communist party line or to a tackily « authentic » Ukrainian folklore, as if Ukrainian culture was all paysan dances and songs. Hrytsak cites the Ukrainian-Canadian historian Orest Subtelny to describe that period: « Everything Ukrainian was not modern, and everything modern was not Ukrainian. » (International flights departed from Moscow, not Kyiv. As late as 1991 a call from the USA to, say, Lviv would route via Moscow.) Hrytsak now lives in postindustrial Lviv. From traditional to modern, from modern to postmodern, all in one lifetime. Modernization for him also means a political program: how to do justice to those who were deprived of access to it.

The terms « modern » and « modernity », Hrytsak notes in the first chapter of the book, took on new meaning in the 19th century: educated classes began to imagine « modernity » as a promise that things would change for better: « Modernity starts when people believe in changes and wish for changes. » The narrative is structured by binary oppositions, which Hrytsak keeps always in sight: tradition and modernity, people and nation, Rus’ and Ukraine. These oppositions shape Hrytsak’s account of the Ukrainian path through « the long 19th century »; from partition through the First World War and the short-lived Ukrainian People’s Republic.

«temperament»,

«how they dress»,

«how they die» .

From the Völkertafel,

c. 1720-1730

«temperament», «how they dress», «how they die»

The chapter on « The long 19th century » opens with a backward glance at the Völkertafel, (Table of Nations), an early 18th-century Austrian oil painting of stereotypes about « ten leading nations ». It includes Poles, Muscovites, an odd « Turk or Greek », but no Ukrainians. Each representative appears in national costume and is ranked on 17 scales, like « character of personality », « temperament », « how they dress », or « how they die. »

The chapter on « The long 19th century » opens with a backward glance at the Völkertafel, the « Table of Nations », an early 18th-century Austrian oil painting of stereotypes about « ten leading nations ». It includes Poles, Muscovites, an odd « Turk or Greek », but no Ukrainians. Each representative appears in national costume and is ranked on 17 scales, like « character of personality », « temperament », « how they dress », or « how they die ». The table makes it obvious that the more Western a nation is, the better it looks. For Hrytsak, the Völkertafel reflects not only the gap between East and West that existed in the early 18th century, but, more importantly, the fact that the Völkertafel’s authors lacked a modern idea of progress: the Völkertafel was, after all, a static piece of furniture, and the different Völker didn’t move up the scale. The word « progress » existed, but in the 19th century its meaning would change to « more, and more, and more; faster, and faster, and faster ». The static Völkertafel would gave way to, for instance, Marx’s certainty that « the country that is more developed industrially only shows to the less developed an image of its own future. » The ensuing conflict, between opponents and advocates of progress, « one of the principal storylines of 19th-century Ukrainian history », is for Hrytsak a story of contested Westernization.

And that’s the point where Hrytsak turns the standard narratives around. He covers the expression of Ukrainian and other nationalisms—typical story for the 19th century, particularly for the dozens of nations omitted from the Völkertafel—but cleverly threads and sometimes inverts the parochial and the cosmopolitan. Hrytsak writes that 19th-century Ukraine might have seemed like a parochial and quiet place—even a bucolic paradise, as Gogol described it in his early works—but only for those who didn’t know the country. « It was like a sleeping volcano: under its surface ran turbulent underwaters, exploding here and there » in uprisings, strikes, and revolutions. Ideological phenomena usually considered parochially « Ukrainian » were drawing from those broader radical streams, on both the Habsburg and the Russian sides.

For instance: nobody is more Ukrainian than the romantic poet Taras Shevchenko—the most prominent Ukrainian figure of the 19th century and the central figure of the national canon, still honored by Ukrainians of different ideological views. Shevchenko updated the old Cossack model of nation—driven by the interests of the Cossack estate—to a nationhood more inspired by the ideas of the French revolution, embracing other estates, first of all peasants. Shevchenko was born a serf in 1814, in the Ukrainian heartland. He moved with his master to Vilno (Vilnius), managed to secure education and freedom, and eventually joined the artistic and intellectual elite of St. Petersburg. (Later he would be convicted for membership in a secret society.) Shevchenko likely never read Edmund Burke, but one of his best-known poems, « Epistle To the Dead, the Living and the Still Unborn », evokes Burke’s « eternal society », articulated in Reflections on the Revolution in France as a contract « not only between those who are living, but between those who are dead, those who are living, and those who are to be born. » In Hrytsak’s account, both Burke and Shevchenko « were drawing on the same source – the new European zeitgeist. » Shevchenko spent most of his life on the Russian side of the partition, not the Habsburg side, though his influence on Ukrainians in the Habsburg Empire is hard to overestimate. For Hrytsak, Shevchenko’s life and work is « proof that the idea of Ukraine emerged due to export of Western ideologies to Eastern Europe ».3

The next ideological booster was Marxism, but this trajectory is more circuitous. Rather a modernization theory than a theory of class struggle, in the late 19th century Marxism enabled what Hrytsak calls « the formula of Ukrainian identity »: « Rus’ + Progress = Ukraine ». Hrytsak turns here to the figure of Mykhaylo Drahomanov, a history professor at Kyiv University in the 1860s and early 1870s, who propounded the idea that since the majority of Ukrainian population were Ukrainian peasants, every Ukrainian should be a socialist and every socialist should be a Ukrainian. Drahomanov was also one of the leaders of Kyiv’s « Hromada », an organization drawn from the intelligentsia. (Hromada members were said to have a volume of Shevchenko poems in one pocket and Das Kapital in the other.) His life illustrates the era’s conflicting pressures and possibilities. His academic and intellectual milieu spanned Western Europe as well as the partitioned Ukrainian world. In 1876, though, he was deported from the Russian empire, along with another member of Hromada, Pavlo Chubynsky (whose poem from 1862 would become an official anthem of the short-lived Western Ukrainian People Republic in 1918, and the official Ukrainian anthem in 1992). Their expulsion was the last point of the notorious Ems Decree, which forbade using the Ukrainian language in the Russian Empire. 4Drahomanov settled in Geneva, where he published Hromada’s newspaper (until his own break with Hromada), and from where he continued to inspire Ukrainian intellectuals in Austrian Galicia, notably Ivan Franko.

Hrytsak’s formula for Ukrainian identity needed the proper environment, after all, and the relatively liberal political culture of the Habsburg Empire served. « National identities need enrooting, » Hrytsak explains in the chapter on urbanization and industrialization. While « identities were amorphous and unstable in the cities of the Russian part, » he writes, the cities of Austrian Galicia « were quite nationalized at the end of 19th and the beginning of 20th century. » Galician urban public spaces—with « newspapers, magazines, coffee shops, etc. »—fostered a free exchange of ideas, growing from the ‘bottom up’, not planted from above. Here Drahomanov’s followers soon outgrew his federalist views: in 1895, the congress of the Rus’-Ukrainian Radical Party (Ivan Franko was one of the founders) included the appeal for Ukrainian independence into its political program.

If all this seems quite dizzying, that’s because it is, and not only for outsiders. Hrytsak’s book internationalizes Ukrainian nationalism; it offers new spins on the figures that Ukrainian readers know, or more likely sort of know. The personages whose faces adorn Ukrainian banknotes—Ivan Franko, for instance, as well as Shevchenko and Lesia Ukrainka—exist in a kind of probationary canon. The sturdier and more standard canon of 19th-century history was, after all, cemented by states and empires. The canons of stateless nations will inevitably seem exotic or opaque. Emile Zola doesn’t need a footnote, for either French or Ukrainian readers, but Julian Bachynsky will.5 It feels as if these figures just missed the chance to introduce themselves.

But the trajectory of Ukrainian nationalism is not even the most complicated story in the book: try the Ukrainian revolution of 1917-1920, which Hrytsak compares to Il trovatore, an opera by Verdi: « its notably complicated plot is impossible to tell without digressing and missing important episodes. That’s why the narratives of the Ukrainian revolution are unavoidably selective. » The First World War brought modernity into Ukraine’s traditional, agrarian universe. Ukrainian territory was an almost inexhaustible reservoir of resources, first of all wheat, and the outcome of that war very much depended on developments here. The war modernized, socialized, and nationalized—nay, Ukrainianized—the peasants, notably those from the Russian Empire who were sent west for the war and encountered fellow Ukrainians there. It was no longer only the intelligentsia that traveled. That is what Hrytsak means when he suggests that « If nations had passports, the date of birth in that passport of Ukraine would be 1914. »

A half century and another world war later, another Western injection would boost national movement again: with the introduction of the transistor radio to the Soviet people (the first was in 1957; mass production came in the 1960s), the forbidden Radio Liberty, Voice of America, and the BBC made their way to the big cities and western regions of USSR, and so did rock music. One cannot march to rock music, Hrytsak notes: the younger generation chose rock over Soviet songs, and eventually « Lenin lost to Lennon ».

And so, over the centuries, with twists and ironies and detours and digressions, the West modernized « the world of Rus’ ». Ukraine rose alongside, and because of, « the rise of the West ». In Hrytsak’s account, « liberal democracy »—along with modern technologies, modern ideologies, parliaments and nations—wouldn’t exist if not for the West. Ukraine wouldn’t exist either. You may not like it, it may sound unacceptable in other parts of the world, but in Ukraine it is a fact, like gravity. You can be modernized successfully as long as you are open to Western influence, be it Aristotle (absorbed by Catholic theologians, and almost unknown in premodern Rus), or The Rolling Stones.

Even by the terrible standards of Europe through two world wars, the scale of violence in Ukraine was abnormal. The American historian Timothy Snyder labeled as « bloodlands » the territories of contemporary Belarus, three Baltic states, Poland, and Ukraine. Ukraine was the worst place to be: in 15 years, from 1932 to 1947, Ukraine experienced not one but several genocides. It was not only how many people died, but also how they died: the deaths of every second man and every fourth woman were violent. Hrytsak, opening a chapter called « The short history of violence » warns readers who have heart conditions.

One of the intriguing questions in Overcoming the Past is how a country with such enormous trauma and with so recent a history of violence (just two or three generations back) managed to make it through the transformations of the last 30 years—including the fall of the USSR and two revolutions—with no large-scale violence.6 Something changed, and suddenly the revolutions were music festivals rather than bloody clashes. Hrytsak’s explanation is geopolitical: with Cold War détente and the signing of the Helsinki Final Act in 1975, dissidents in Soviet republics (Ukraine, Lithuania, Georgia, and Armenia) seized the rare opportunity to speak up, both for human rights and for national rights. In the Ukrainian case, this harkened back to democratic traditions inaugurated in the late 19th century, though now the slogans reflected not only interior or « national » issues, but global ones: human rights, freedom of thought, freedom of speech, and democracy.

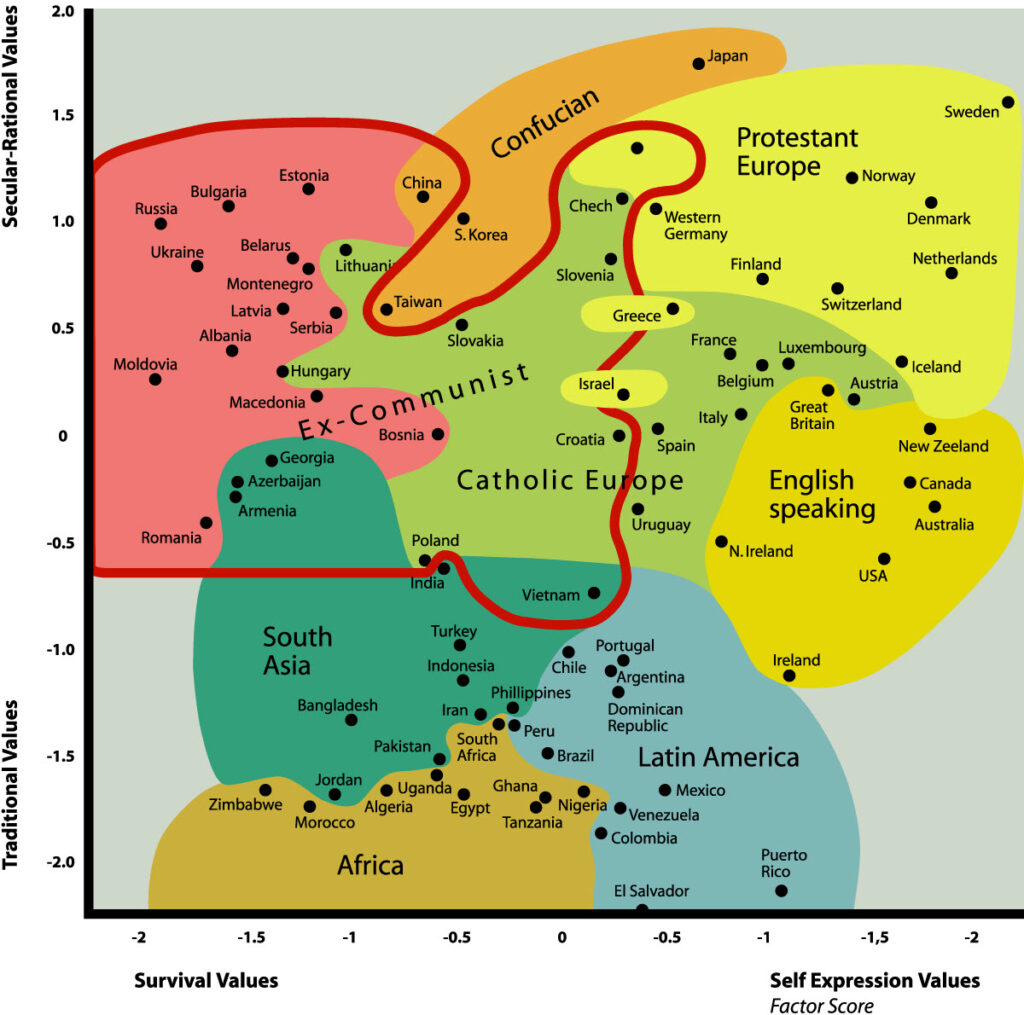

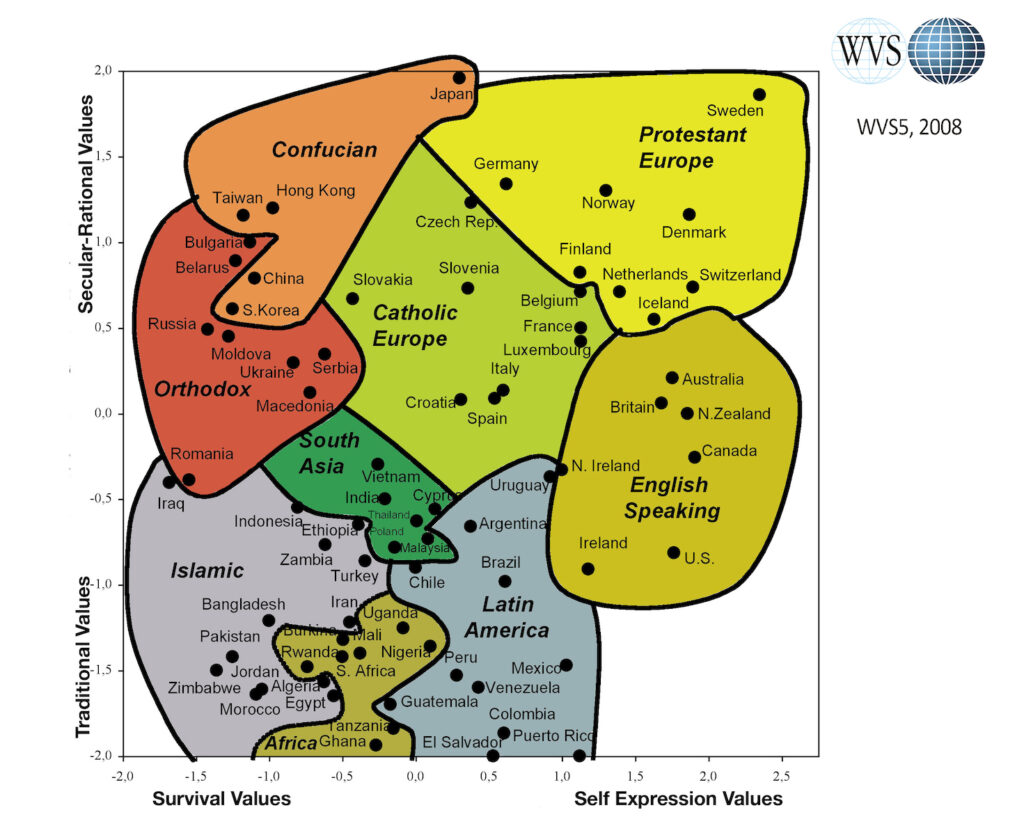

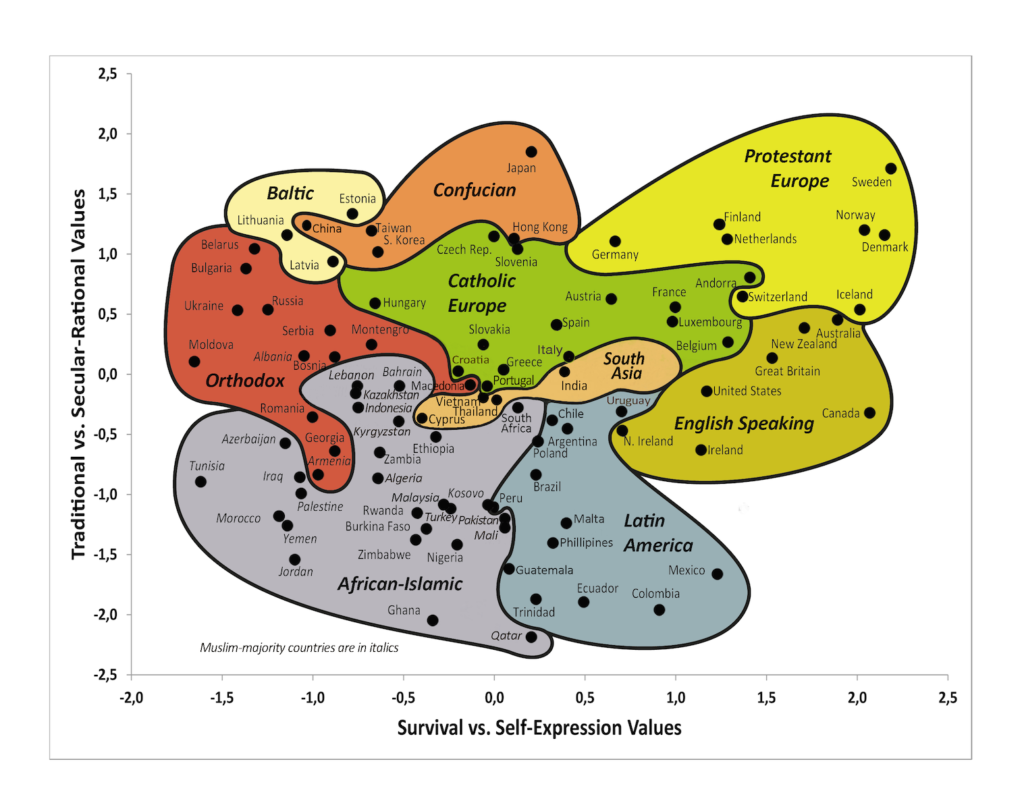

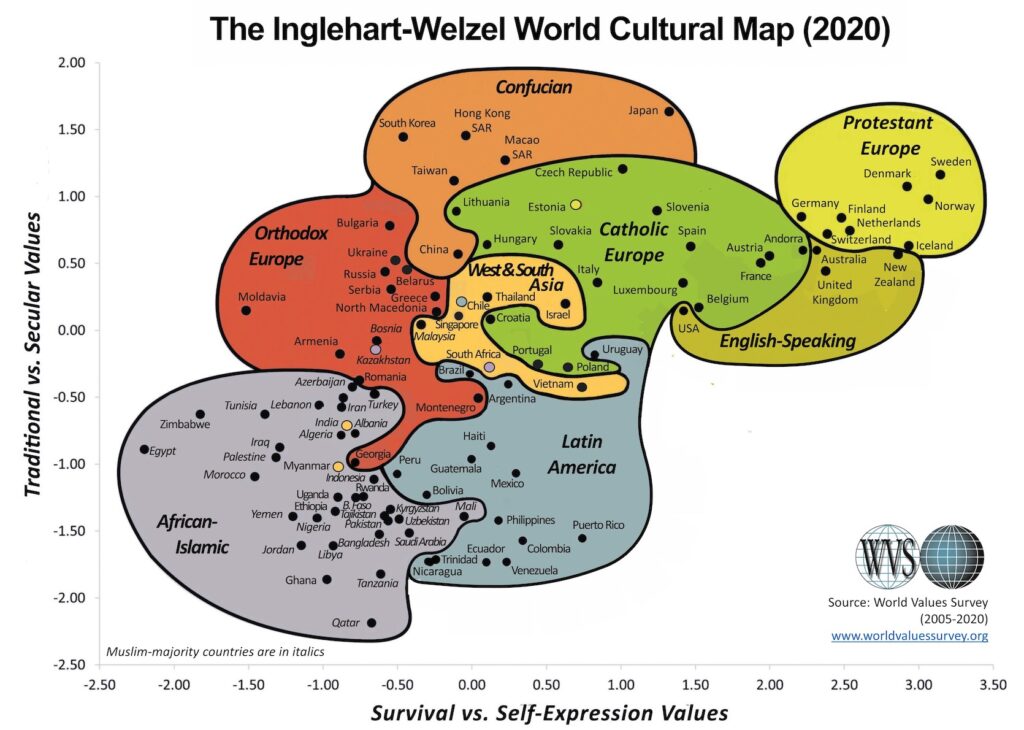

The World Values

Survey is the

Völkertafel of our

era.

The Völkertafel of our era

… The idea that « values » are, in fact, measurable and visualizable data, collectable in the field … the World Values Survey is the Völkertafel of our era. It began as the European Values Study but has since expanded to more than 120 countries. « Survival values » vs. « self-expression values », « traditional values » vs. « secular-rational values »; Ukraine first submitted to these measurements in 1996. …

Inglehart, R., C. Haerpfer, A. Moreno, C. Welzel, K. Kizilova, J. Diez-Medrano, M. Lagos, P. Norris, E. Ponarin & B. Puranen (eds.). 2021. World Values Survey: All Rounds – Country-Pooled Datafile. Madrid, Spain & Vienna, Austria: JD Systems Institute & WVSA Secretariat. Dataset Version 2.0.0. doi:10.14281/18241.15.

In other words, liberal values. A step back: as a public intellectual, Yaroslav Hrytsak is to a large extent responsible for introducing the concept of « values » into Ukrainian public discourse, in particular the methodology and categories of the World Values Survey, inaugurated by the American political scientist Ronald Inglehart in 1981. It began as the European Values Study but has since expanded to more than 120 countries. « Survival values » vs. « self-expression values », « traditional values » vs. « secular-rational values »—it is the Völkertafel of our era. Ukraine first submitted to these measurements in 1996; Hrytsak now uses them to explain Ukraine to Ukrainians. The idea that human beliefs and values are, in fact, measurable and visualizable data, collectable in the field, has easily prevailed over the older vocabularies that dominated in domestic Ukrainian discussions up through the 1990s: vocabularies of « national mentality », say, or Samuel Huntington’s apocalyptic « clash of civilizations ». Hrytsak’s main message is that values may—and, in the case of Ukraine, should—change, and that usually it takes a generation.

Hrytsak has praised all three Ukrainian uprisings on Maidan Nezalezhnosti on Kyiv: the student strike known as the Revolution on Granite in 1990, the Orange Revolution in 2004, and Euromaidan in 2013-2014. He examines the latter two revolutions in Overcoming the Past: nary a decade apart, they make a generational change particularly visible. In 2004, the Orange Revolution had a leader, future president Viktor Yushchenko; his name was the rallying cry. But the 2013-2014 Euromaidan belonged mostly to a generation that has more in common with its global peers than with older compatriots: Hrytsak sees Euromaidan as part of the global precariat movement that began in 2011 with Occupy Wall Street and the Arab Spring, and that continued in countries like Chile (2019) and Belarus (2020). All were responses to rising inequality and a shrinking middle class; all drew heavily from the younger population, born after the Soviet Union fell apart, that grew up in the period of elevated expectations and were thus the most aware of their losses. No wonder they rebel. Their future seems grave and uncertain. Who can promise them « progress »? The plots in Chile and Ukraine, Hrytsak observes, are almost identical. Student protests are crushed by authorities, but then snowball as the media expose the brutality. The authorities exert more pressure in turn. Non-violent protest gives way to bloody clashes with police; street fighters use Molotov cocktails and cobblestones. Thousands of citizens provide food, water, medical assistance, and, yes, assist with the Molotovs, too.

« No leaders, the core consists of young, educated people with university diplomas, whose demands are hard to define, and even harder to measure – respect for human dignity and justice. » The structural affinities, Hrytsak suggests, extended to language, too: « The language of their revolutions was the language of values, not interests. » The newer generation avoids hierarchical organizations and is used to communicating online. The organizational architecture reflected the egalitarian ethos of social media. Party symbols were banned during the first week. Opposition parties had Euromaidan’s mandate to negotiate with the authorities, but the leaders of those parliamentary parties could not promise anything that Euromaidan would not approve. Nor could international leaders: Euromaidan didn’t accept the deal with notorious then-president Viktor Yanukovych (a deal facilitated by the foreign ministers of France, Germany, and Poland), and he fled the country. The movement had no leader, and was thus unbreakable. Yet Hrytsak warns that the « energy of horizontal connections » has its downside: to reboot a country, he argues (in Ukrainian, « reboot » doesn’t sound quite as techy-neoliberal as it does in English), young people will have to join political parties and at least provisionally accept the inevitable hierarchies thereof, while voting and speaking up on a daily basis.

Of the « revolutionary wave » that swept through Hrytsak’s global 2010s, most protests failed. Euromaidan is one of the few that succeeded: Yanukovych fled to Russia in disgrace, as did his close allies, and Ukrainians have since had several elections, fair and transparent. The goal of joining the EU and NATO was inscribed in the Constitution in 2019, no longer a matter of political discussion as it was just ten years ago. Ukrainian political life has been turbulent, unpredictable, and sometimes very odd, and the pace of reforms may be disappointing, but no one can say Ukraine does not enjoy freedom and democracy. Of course, any war risks pulling a society down to survival values, and Russia occupied Crimea and parts of eastern Ukraine in 2014. Nonetheless, Hrytsak shows with his charts that the currents were pushing Ukraine toward the values of self-expression. Russia and Belarus, too, at least on the World Values Survey map, but Ukraine has longer democratic experience and an advantageous political climate. The combination means Ukraine has a chance.

Did Hrytsak’s book predict anything of this? Not precisely; its predictions were more general: « While Ukraine is increasingly globalizing, » he writes in the last chapter of the book,

the global world is increasingly Ukrainizing. Ukrainian problems — political instability, increasing inequality, aging population, Russia at the door, are the problems of the entire world. And since Ukraine became again the strategically important frontier after the fall of the Soviet Union, Ukrainian developments potentially may have global consequences. The ongoing war in Donbass is more than just a war between Ukraine and Russia; it is the war for outlining the future world.

It’s strange to think that non-Ukrainian readers would find such a prediction resonant now. Hrytsak’s book was written to secure for his country a story line in the global tale; an irony of this review is that its readers, expressing sentiment or solidarity from afar, now try to secure a place for themselves in the Ukrainian tale.

A more bitter irony of writing an essay on historical narrative is that the Russian invasion is driven by a maniacal desire to rewrite history, or to turn back time. The war is not simply with Ukraine, but with the turn that history took in the late 1980s. Hence Putin’s obsession with history, his nostalgia for Russian might. His boring historical lectures (warnings that the world ignored) make it seem like an obsession all his own, but he is not the lonely lunatic so often pictured by the West; he is also a product of Russian society, political traditions, and thirsts. Any war is archaic, but this one is archaic on a second level: it is also the war for the archaic, a war to destroy the tracks of Ukraine’s path to modernity.

« I am in the Team —

Effectivity,

Responsibility, Order

», 25 September

2010, Odessa. From

Europeans (2015)

YAMANDÚ ROOS

« I am in the Team — Effectivity, Responsibility, Order », 25 September 2010, Odessa

Hrytsak has often compared Ukraine to a bumblebee, citing the British Ambassador to Ukraine in 1994, who referred to « the bumblebee flight myth »: engineers, the story goes, proved that bumblebee flight is not consistent with known aerodynamics, and yet somehow it flies. Ukraine was proved to not exist, but it does. International pundits predicted a civil war in the 1990s that would devolve into a catastrophe worse than the Balkans — and it never happened. They expected a split into two or more parts in the 1990s and in the 2000s, and again it never happened. Almost no one believed that Euromaidan might prevail, and it did. In 2022, Western military experts calculated that most of Ukraine’s territory, including Kyiv, would be occupied by Russian forces in 48 to 96 hours. After a month of war Ukraine was bleeding, but the plan failed dramatically.

The riddle of bumblebee flight was solved in the early 2000s: with new technologies, such as aerodynamic modelling and sophisticated cameras, engineers explained how. Hrytsak, throughout his career, has argued against framing Ukrainian history as a tragedy. It is indeed full of tragedies, but it isn’t a sequence of failures. He has tried to prove that Ukrainian history was, despite its thorns and intricacies, normal. Most of Hrytsak’s predecessors ended up explaining Ukrainian failures. In his book he bravely explains Ukrainian victories.

« As a modern nation Ukraine was born in the fire of war and revolution, » Hrytsak states about the context of the First World War, which turned the vision of Ukraine into political reality. When revolutions and wars are equipped with online cameras, the whole world can see: a bumblebee can fly.

Photo by Lesya Ganzha, Kyiv, 24 January 2014, during Euromaidan. The National Philharmonic of Ukraine is visible in the photograph’s upper left, beyond the barricade.

- A Tatar ship was raided on the Dnieper river; the Crimean khan complained to the grand duke of Lithuania that the perpetrators were Cossacks, then the grand duke’s subjects. Cossacks were martial people of different origins who had settled the lands south of Kyiv. Hrytsak describes them as « pirates of the steppe », « social bandits » in Eric Hobsbawm’s terms—not a pejorative, more like Robin Hood. ↩︎

- Another bombshell history published in 2021 focused precisely on the Commonwealth: in The Ukrainian Universes of the Commonwealth (Українські світи Речі Посполитої. Київ: Laurus, 2021) by Natalya Starchenko. Starchenko challenges the usual notion (Hrytsak’s too) that one of the main causes of the 1648 revolt was the exploitation of peasants; she also cautions against projecting the later histories of serfdom and chattel slavery onto earlier eras. ↩︎

- Shevchenko pops up at every Ukrainian existential moment. During Euromaidan, Shevchenko’s stern visage found its way into street art: walrus mustache, bald head in the open air or under the giant fur cylinder of a hat. The iconic photo with the hat was taken after his comeback from exile in Kazakhstan: under his traditional Ukrainian clothes, a dress coat may be noticed. His birthday, March 9, is the occasion of « Shevchenko days », which this year fell during the invasion. His writings on the Cossack wars can resonate in the current war. The Ukrainian Defense Minister, Oleksii Reznikov, posted a flack-jacketed selfie in front of Shevchenko’s statue in Kyiv; Shevchenko memes abound. ↩︎

- Russian emperor Alexander II issued the decree while vacationing at the German resort Bad Ems. In its 11 points, it banned both the publication and importation of books in the Ukrainian language—original texts and translations. It also banned the Ukrainian language from the theater, from concerts, public readings, and elementary education. Ukrainian books had to be confiscated from the school libraries. Authorities were urged to check the loyalty of schoolteachers: suspicious ones were to be transferred to ethnic Russian regions and replaced by the teachers from there. (The decree recommended such transfers in general.) The Kyiv branch of the Geographical Society was shut down, as was one of the newspapers. The Ems decree remained in effect until the Russian revolution of 1905. ↩︎

- Julian Bachynsky, a young Marxist intellectual in Lviv, part of the student circle that surrounded Franko, articulated the appeal for Ukrainian independence in Україна Irredenta (1895). Hrytsak’s intellectual biography of Ivan Franko has been translated into English by Marta Daria Olynyk: Ivan Franko and His Community (2019). While we’re at it, Hrytsak’s own intellectual hero is not Ivan Franko but Ivan Lysyak-Rudnytsky, a great historical essayist. Lysyak-Rudnytsky was from an influential Galician family of liberal politicians, journalists and intellectuals (his mother was the most prominent figure in the women movement, a vocal feminist); a student at Lviv University until 1939, he would spend the rest of his life in Europe, the USA and Canada. ↩︎

- The 2004 Maidan, also known as Orange revolution, was like the 1989 carnival of Central European non-violent revolutions, transplanted 1000 km to the east and delayed 15 years. The 2013 protest began as non-violent too. The beatings, killings and kidnappings in Kyiv in January and February 2014, by special forces, pro-Russian paramilitary groups and paid thugs, were approved, provoked, and assisted either by the Yanukovych ruling clan, or by Russian agents provocateurs, at least to some extent, and it’s also clear that the separatist coups and war in the Donetsk and Luhansk regions would not have happened if not for Russian infiltration. ↩︎