On catastrophic learning

(Photograph by Bror Brandt, August 1956, Finnish Heritage Agency, Finland, CC4.0.)

The Zaporizhzhia Nuclear Power Plant in Ukraine, one of Europe’s largest nuclear facilities, has improbably made it through more than three years of war, occupation, and direct military threats. Before the war, the plant provided about one fifth of Ukraine’s electricity; it also exported power to Europe. It had a staff of twelve thousand highly skilled workers. Russian forces seized Zaporizhzhia on 3 March 2022. Most of the Ukrainian staff fled; the plant has since been subjected to drone strikes and shelling. In June 2023, the Kakhovka Dam was breached; its water reservoir is important to the plant’s cooling infrastructure. Now controlled by occupying forces, Zaporizhzhia is severely understaffed and no longer generates power — a situation that itself dramatically increases the risk of overheating and failures.

Reckless and destructive interference with Ukrainian nuclear facilities has been one of the most alarming features of this war. Chornobyl Nuclear Power Plant was occupied before Zaporizhzhia, on the very first day of the invasion, 24 February 2022. Since then, Russian troops have excavated, mined, and shelled Chornobyl’s irradiated exclusion zone. They destroyed radiation monitoring stations and looted dosimeters, disrupting data flows to the International Radiation Monitoring Information System (IRMIS). On 26 April 2022, the anniversary of the 1986 Chornobyl catastrophe, the European Commission urged Russia to allow Ukrainian operators to resume safety procedures. Most European states, together with Australia, Canada, Japan, New Zealand, South Korea, Turkey, the United Kingdom, and the United States, reiterated these demands in August, and the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) launched a series of missions to reach Ukrainian nuclear power plants across the front line. On 14 February 2025, a drone pierced Chornobyl’s outer shell and provoked a fire, increasing significantly the risk of a nuclear disaster.

You’re reading this essay for free. With a membership, you can read the full magazine, and you get access to our fabulous Library.

Here’s our offer: 3 months unlimited digital access + 1 print edition for € 38,00 € 19,00

You’ll get Issue Eleven in print as your first magazine, right to your mailbox.

The International Atomic Energy Agency was established in 1957 by the United Nations, at the height of Cold War escalation, to promote the peaceful use of nuclear technology and prevent the proliferation of nuclear weaponry. Zaporizhzhia, though, was unprecedented — a potential radiation disaster amid a full-scale war — and the IAEA’s security protocols proved inadequate. Those protocols, as it happened, were developed in peacetime, and what shaped them was the « lessons » learned from Chornobyl.1 Ironically, it was a war between the two heirs of Chornobyl, Russia and Ukraine, that forced the agency to establish new protocols.2

Despite extensive assaults, the Zaporizhzhia reactors have proven resilient. Is this surprising? Yes, no, it depends on how the question is asked. It also depends on when the question is asked, and on when the reader is reading this essay. At the moment of writing, at least, to explain Zaporizhzhia is to explain a catastrophe that didn’t happen, or that so far hasn’t happened. It is possible, while doing that kind of explaining, to find a sliver of something like optimism in catastrophic times.

Let’s cling to it, at least for a moment. One explanation for Zaporizhzhia’s endurance is its use of VVER reactors — a water-water energetic reactor model significantly safer than the graphite-moderated RBMK reactors used in Chornobyl in the 1980s. The VVER is as different from its RBMK predecessor as helicopters are from airplanes: both fly, but with entirely different mechanics. Following the Chornobyl disaster, many Eastern European states transitioned to VVER reactors. These safer designs, it is bitter to learn, were developed well before the 1986 accident. (The RBMK reactor design used at Chornobyl was chosen not for safety but because it was cheaper to build. The Soviet nuclear program, as Per Högselius and Achim Klüppelberg note in their history of the « Soviet nuclear archipelago », was supposed to demonstrate socialism’s superiority over capitalism; its real history suppressed dissent and manipulated data.3) Had Chornobyl not occurred, the Soviet Union might have continued installing unsafe RBMK reactors all over eastern Europe and northern Eurasia, and a Chornobyl-type catastrophe would have happened in a different place.

What Zaporizhzhia’s historical background illustrates is how global nuclear security has been shaped into our own time: not by hypothetical scenarios, but by real, unfolding catastrophes. It is, grimly, a case study in catastrophic learning. It also serves as a metaphor for our epoch. It exposes the illusion of stable systems and underscores the urgency of finding meaning, cohesion and care amid institutional collapse. Not merely a war zone or energy site, it is a grotesque theater of technology without use and humanity without reason. Control without mastery, survival without certainty.

« What is a double-headed eagle? It’s a Chornobyl chicken. » A late Soviet joke, the getting of which requires some knowledge of heraldry: the coats of arms of the Seljuks, the Mamluks, the Palaiologos, the Romanovs, and the Habsburgs all featured double-headed monsters. The joke compresses centuries of imperial vanity and hubris into an allegory of ineptitude: feathered monsters, looking in two opposite directions, blind to everything straight ahead.

But the punchline gets it wrong: double-headed birds are as rare in Chornobyl as they are anywhere else. The actual reverberations of Chornobyl in politics and society are far vaster and more convoluted. It was neither the first emergency involving the « peaceful atom », nor the first disaster within the nuclear archipelago. What distinguished Chornobyl was the scale and scope of its impact — both immediate and longterm, both direct and cascading — as well as its symbolic power.

Chornobyl profoundly reshaped many parts of Europe — East, West, and Central. It galvanized Green politics, spurred anti- nuclear activism, advanced medical research, and led to sweeping changes in industrial regulations. Apart from Covid-19, no other peacetime emergency has had such far-reaching consequences. The USSR’s disintegration was hastened by it, as Scott Kaufman and others have argued. In Ukraine, the regime’s failure to respond transparently and effectively would trigger widespread disillusionment and catalyze, over time, what the historian Serhii Plokhy has termed « eco-nationalism »: a potent blend of environmental anxiety and political awakening in emerging post-Soviet countries.4

The fallout was not only radioactive but geopolitical. Afterward, nuclear energy programs across eastern and central Europe were abandoned: four reactor sites in the Volga region, one in Crimea, and dozens more across Poland, East Germany, Czechoslovakia, Bulgaria, Austria and Lithuania. Only after a decade and major political change did the nuclear industry cautiously resume, and then only with new, safer reactor designs.

Western Europe, too, reeled from the disaster. Chornobyl remains associated with a surge in cancer rates — especially thyroid cancer — and its victims are still called the « Chornobyl generation ». The radioactive cloud that swept across the continent underscored a shared vulnerability — indeed made a shared « European » fate terribly vivid.5 In countries like West Germany and Italy, where nuclear power had once enjoyed strong political support, public outrage spurred referendums and swift legislative action. Within months, both countries passed resolutions to phase out reactors and halt expansion plans, and yet this turn away from nuclear power came without a clear alternative. Germany, in particular, substituted nuclear plants with fossil fuels, becoming the continent’s largest importer of Russian gas and one of its top consumers of coal. In a now-bitter irony, that moment’s energy transition — intended as a moral response to ecological risk — made Germany the biggest carbon emitter in Europe and would deepen its entanglement with Russia’s war of petroaggression. « Lessons » from Chornobyl produced, over time, perverse outcomes. Technology was out of sync with politics: engineers learned to build safer reactors, but politicians would fail to prevent an oil-and-gas-fueled war. (Now, as Germany half-heartedly seeks to reverse those energy policies and to rely no longer on its belligerent partner, the prospect of nuclear revival has resurfaced.)

You’re reading this essay for free. With a membership, you can read the full magazine, and you get access to our fabulous Library.

Here’s our offer: 3 months unlimited digital access + 1 print edition for € 38,00 € 19,00

You’ll get Issue Eleven in print as your first magazine, right to your mailbox.

Chornobyl’s aftermath has inflected Green politics as well, in ways so broad they can become easy to miss. If not for Chornobyl, the Green movements that arose during the Cold War might have faded in the post-Cold War era of neoliberal globalization. But Chornobyl, and its uncanny synchrony with Gorbachev’s perestroika, reinvigorated Green movements across the continent, from the United Kingdom to Poland.6 The Soviet Union’s « local » crisis generated global lessons. Green politics has evolved through its own catastrophic encounters. Initially galvanized by Cold War fears of nuclear weapons, its anti-nuclear stance was reinforced by Chornobyl. Chornobyl was taken as a repeatable template rather than a tragedy specific to, say, Soviet perestroika. The fight against nuclear weapons morphed into a fight against nuclear power plants, a stance only strengthened decades later by the Fukushima disaster of 2011.

Today, though, in the context of accelerating climate crises, this orientation of Green politics seems increasingly untenable. What began as a principled rejection of atomic modernity now resembles a nostalgic holdover from the 1970s and 1980s — one that clashes with the twenty-first-century imperative of deep decarbonization. Even after COVID-19, even amid climate acceleration, European Green parties, with an uneasy mix of old doctrines and new realities, continue to oscillate between principled resistance and strategic compromise. War in Eastern Europe, with its nuclear threats and energy blackmail, once again puts them to the test.

Chornobyl reverberated in social thought, too. Intellectuals and activists, while grappling with a specifically Russo-Ukrainian breakdown, extrapolated a wider model of systemic failure: a risk politics of late modernity. In 1986, the German sociologist Ulrich Beck captured the zeitgeist in his now-classic Risikogesellschaft: Auf dem Weg in eine andere Moderne (translated to English in 1992 as Risk Society: Towards a New Modernity). The book was finished just before Chornobyl but published when the Soviet « liquidation » efforts were at full swing. Beck, in his long-running dialogue with Marx’s thought, endeavored to reorient the analysis of capital — the production and accumulation of private goods — to what he called « public bads » such as radiation, climate change, and infection, costs that could not easily be confined or compensated. In Beck’s « new modernity », societies were becoming more concerned with redistributing public bads than private goods. The radioactive plume drifting across borders became a physical embodiment of what Beck, in a powerful diagnosis, called the transboundary nature of modern hazards.

Beck died in 2015; in an unfinished book published posthumously in 2016 — The Metamorphosis of the World: How Climate Change is Transforming our Concept of the World — he would propose « emancipatory catastrophism » as something like a remedy: the idea that global disasters, while devastating, could foster new solidarities and institutions. The process was not exactly intentional, like revolution or reformation; the metamorphosis he was concerned with would « proceed latently, behind the mental walls of unintended side effects. » Still, if Risk Society diagnosed the problem, Metamorphosis offered a tentative hope: that from catastrophe might emerge a deeper cosmopolitanism. Even the grimmest tragedies could yield converse wisdom; World War II, Beck posed, shaped cosmopolitan institutions such as the United Nations or the European Union. When it came to climate change, emancipatory catastrophism was, in Beck’s account, the only thing that could save us. If his old theory of risk society was about « the negative side effects of goods », Beck wrote, his new idea of metamorphosis was about « the positive side effects of bads ».7

It is curious to revisit Beck’s works now, saturated as the world is with a sense of its own ending. Beck’s optimism (if optimism is the right word) is in some ways out of sync with the eschatological grammars through which our discourses have moved since the dawn of the atomic age.

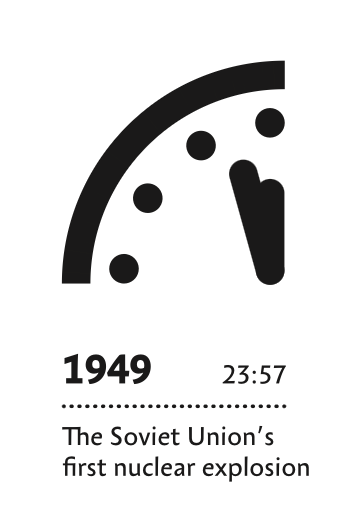

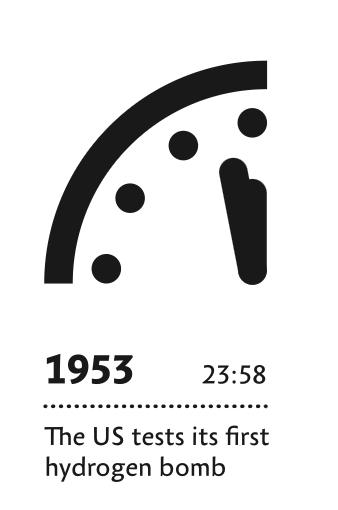

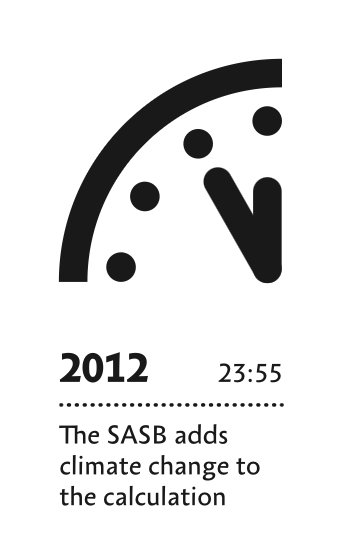

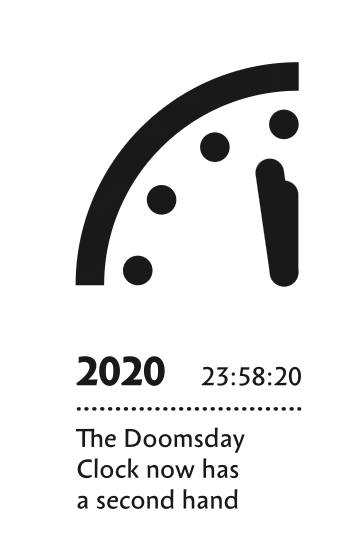

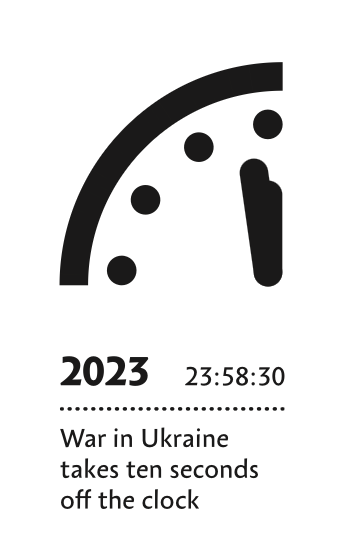

We can start with the simplest such grammar. The Doomsday Clock was introduced in 1947 by former Manhattan Project scientists who had helped develop the atomic bomb. They intended the Clock as a symbolic warning about humanity’s proximity to self-destruction. They set it at seven minutes to midnight. For decades, the Clock has oscillated in response to arms races and, later, climate threats. The measurement is charmingly one-dimensional. It was born of an era that assumed, quaintly, that disasters can be anticipated and prevented. The Cold War, that is to say, offered a seductive eschatology: the world could end at any moment, but also could be saved by negotiation, deterrence, or disarmament. Apocalypse was both luridly imminent and saliently preventable — a narrative structure that made fear productive rather than paralyzing. Catastrophes did happen, but the big one was narrowly avoided. Closeness to planetary destruction did, after all, prompt political leaders to learn from their fear of mutual annihilation, as in the Cuban missile crisis (15-28 October 1962) when U.S. President John F. Kennedy and Soviet General Secretary Nikita Khrushchev stepped back from the brink of war, ushering in a period of détente.8

The early climate-change reformers were likewise, in their way, optimists about the possibility of politics to do things. From the 1960s onward, many scholars and politicians believed that once climate catastrophe was widely acknowledged and consensually understood, coherent political responses would naturally follow. How naive it all looks now, as the science of climate change is clearer than ever, yet political action remains gridlocked or performative.9

The twenty-first century’s eschatology is, accordingly, pluralistic: climate collapse, financial meltdown, a new world war, and (most recently) unregulated AI. It is not surprising that a pervasive and manifold sense of doom would revive nostalgia for the Cold War, when, at least, the enemy (on either side of the Iron Curtain) could be defined in crystal-clear ideological terms. Nor is it surprising that « permacrisis » (a term coined in the 1970s for something else) would be Collins Dictionary’s Word of the Year in 2022, or that an academic term like « polycrisis » (a term to which we will return) would feel like it needs no explanation. We lurch from one emergency to the next, a politics of reactive, short-term decision-making aimed solely at damage control. One « state of exception » follows another, with no satisfying understanding of their distinctness or their interconnectedness. Better to call it a chain of exceptions, which normalizes the policies that respond to the last disaster without anticipating the next.

The eschatological literature is vast; let us take partial stock. In 2008, the climate researcher Timothy Lenton spoke of « catastrophic tipping points »: catastrophic events — megafires, heat waves, devastating floods, pandemics, and genocidal wars — that have occurred more and more frequently, with a rate of acceleration that has surprised even the most bitterly concerned scholars.10

In 2011, the political theorist Timothy Mitchell’s Carbon Democracy: Political Power in the Age of Oil furnished historical depth. His premise was that the physical properties of energy systems — coal, oil, renewables — have shaped economies, obviously, but they’ve also made particular political forms possible, and conditioned those forms. Thus have centralized fossil fuel infrastructures historically enabled authoritarian governance and limited democratic participation. Energy transition — uneven, contested, deeply political — would in turn shape not only thermodynamics but also geopolitics. Mitchell’s question was whether renewable systems would be locally distributed, or simply re-centralized through global tech monopolies. It was a call for carbon democracy against carbon capital — against, that is, the tendency of capital to accumulate in monopolies and cartels.

Materials limit possible political forms; carbon’s political forms in turn drive us crazy. In a 2012 paper, the climate scientist Kevin Anderson pondered the psychological compartmentalizations and cognitive dissonances common (or necessary?) in our era: stark warnings coexist with business-as-usual practices. Even well-informed climate scientists and policymakers, he noted, had engaged in forms of denial by embracing « impossible arithmetic » — targets and timelines that could not be reconciled with existing emissions trajectories and carbon budgets.11 This dissonance enabled a kind of double-consciousness — still familiar thirteen years later — where catastrophic knowledge exists alongside unchanged practice.

(Is it a brain problem? — cognitive information overload leading to traumatic forgetting, the collapse of interpretative hierarchies, the plausible and the implausible, the proven and the unproven? With knowledge no longer cumulative and analytical, societies oscillate between panic, denial, and paralysis, while time runs out? Maybe. Engineers working on artificial neural networks speak of « catastrophic interference »: when an excessive amount of new data is processed, it can overwrite existing patterns, leading to abrupt erasure of previously recorded information. We could call it artificial oblivion.)

It would be wise, then, to look to warnings against both catastrophism — which leads to nihilism — and false optimism — which breeds complacency. This was the thrust of the environmental and legal scholar Dale Jamieson’s Reason in a Dark Time: Why the Struggle Against Climate Change Failed — and What It Means for Our Future, published in 2014. Climate change, Jamieson suggested — with its scales of space and time, its diffuse causality, its resistance to direct experience — challenged conventional notions of responsibility, and even defied our moral frameworks. A coherent politics would need, therefore, a robust faith and sturdy « Green virtues »: humility, patience and temperance, virtues that resist both despair and hubris.

Or it would need new narratives. In 2016, Amitav Ghosh, in The Great Derangement: Climate Change and the Unthinkable, attributed our inertia not to ignorance but to narrative failure. Climate change, he proposed, escapes our most fundamental genres — tragedy, comedy, redemption. It lacks protagonists, villains and closure. Ghosh urged new metaphors, new stories, new modes of attention — an expansion of the narrative imagination — that would link local lifeworlds to planetary processes.

Around the same moment, a constellation of thinkers — from anthropologists and feminist theorists to Indigenous scholars and environmental humanists — outlined modes of living that did not seek the restoration of a lost order but embraced the improvisational, the partial, and the collective work of making life possible in damaged worlds. In 2015, Anna Tsing’s masterpiece, The Mushroom at the End of the World, looked to matsutake foragers in disturbed ecologies who, in her account, foregrounded an ethic of salvage over restoration: communities that navigated collapse not through mastery, but through fragile interdependence and attentiveness to what still grows in ruins.12 Resilience, in this emerging lexicon, would not be a return to normal but a reorientation toward continuity within disruption.

Rebecca Solnit’s research into historical disasters would likewise reveal how grassroots responses evinced mutual aid rather than selfish panic — suggesting that social solidarity could flourish not despite disaster, but because of it. These insights were echoed by Donna Haraway’s more abstruse meditation, in 2016, proposing a successor to the « Anthropocene » (the now-familiar name for the geological epoch dominated by humanity) in the form of a « Chthulucene », drawing inspiration from the Greek root chthon (earth, or soil). « Staying with the trouble », Haraway suggested (as opposed to imagining some tabula rasa), would cultivate « response-ability » among human and nonhuman collaborators. Rather than seek control or return, Haraway proposed sympoiesis — making-with — as a practice for inhabiting ongoing catastrophe.13 These perspectives unsettled the logic of systems thinking that would imagine catastrophe as a problem to be resolved by, say, the right models, metrics, or market incentives. They shifted the discourse of climate response away from a fantasy of resolution, and toward a posture of cohabitation.

The most brilliant books, alas, do not capture carbon, and some eschatological grammars have shifted in the last decade towards a politics of mitigation on an « uninhabitable Earth », as David Wallace-Wells put it in 2017. Regardless of future emissions reductions, the carbon already released will continue warming the planet for decades. At what point does the work of mitigation itself become a form of denial? Jem Bendell’s framework of « deep adaptation », first articulated in 2018, sought to confront this temporal predicament directly.14 Rather than pursue mitigation strategies that assume business-as-usual, Bendell pushed preparation for civilizational breakdown, posing four key questions: What do we most value that we want to keep? What could we let go of so as not to make matters worse? What could we bring back that we have lost? What shall we make peace with that we cannot change? This framework, suggesting that collapse is not a possibility but an inevitability, was controversial when it was articulated, for it seemed to some readers like veering into despair, and yet it also spoke to a public appetite for vocabularies that acknowledge the scale of loss.

In parallel to these profound reflections, the global right was developing its own catastrophic grammar. In the US, « Dark Enlightenment » thinkers cast a so-called European civilization as a spent force. Their radicalism cloaks itself as realism: only by tearing down liberal institutions, they argue, can planetary catastrophe be averted. This nihilistic revisionism would converge with the authoritarianism of Russia, Qatar, and other petrostates to form a transnational counterrevolution. What animates this hyperactive coalition is a shared enemy: meaningful climate action, and the redistribution of wealth, power and resources that would have to accompany a genuine global transition to a low-carbon economy.

And now? The modern world races forward with all its technological might, yet remains trapped in a reactive cycle of disasters. On 28 January 2025, one week after Donald Trump’s second inauguration, the one-dimensional Doomsday Clock moved to 89 seconds before midnight — the closest it has ever been to the end of the world. The war in Ukraine, now in its third year, continues to strain the clock’s second-hand. By targeting nuclear plants, refineries, and power stations, Russia weaponized energy infrastructure on a scale unseen since the Cold War.

Expectations from seeming historical precedent fail to illuminate. Economic sanctions have not deterred Russia from massacring its neighbor. The world’s stock markets did not crash with the invasion — quite the opposite has happened. The European Union and the United States have not been consistent in defending their values from Russia’s assault. So far, the Russian Federation has not collapsed in the way the Austro-Hungarian Empire did in 1918 and the Soviet Union in 1991.15 The doctrine of deterrence no longer holds: the aggressor now defines the catastrophe not through nuclear launch codes, but through the destruction of civilian energy grids. The sense of despair can even create a perverse wish for an old-fashioned catastrophe, as if, in the face of apathy or denial, only a Chornobyl-grade shock could jolt us to action. Yet it might be truer to say that we’ve already passed the Doomsday Clock’s midnight, without a bang but with a thousand whimpers.

Here it is worth noting the limits of « polycrisis » as a term. Coined by the French philosopher Edgar Morin in 1993 and popularized in the last decade by the economic historian Adam Tooze, among others, polycrisis handily describes our current condition: multiple emergencies, not merely simultaneous but interconnectedly amplifying one another in a structural entanglement. The term, while a welcome rejection of monocausal thinking, can devolve into conceptual overload: with every cause linked to every effect, the ability to learn from crises is overwhelmed by their simultaneity. The discourse itself risks paralysis — or it creates a temptation for centralized control: the octopus-logic of managing all fronts at once. It is hard to learn from polycrisis; the term has its own totalizing pull. Polycrisis spurs indiscriminate pessimism — an inverse of the indiscriminate optimism that defined Pollyanna, the irrepressibly cheerful young heroine of the eponymous American children’s novel. What defines both extremes, Pollyanna and Polycrisis, is their failure to discriminate. We need other ways to think.

Because humanity has failed to act preemptively on climate change, necessary responses will follow catastrophes rather than prevent them. There will be no singular apocalypse, no clean ending that resolves our contradictions. We have already inherited the consequences of proliferating catastrophes, overlapping and recursive, each compounding the failures of the last. To enter the future is to inherit a catastrophe. We are living after the age of scientific revolutions; perhaps we are living only in the era of catastrophic learning. The question, then, is not whether we can escape it but how we live with it and after it, and how we can influence its direction. The wish, of course, is easily stated: toward justice rather than domination, care rather than extraction, and collective flourishing rather than individual accumulation. If we are learning in the process, then we are worthy of survival in the only sense that matters — capable of creating conditions where life, in all its damaged beauty, can continue.

In the meantime, Zaporizhzhia endures, neither fully functioning nor fully broken. If, by the time the reader encounters this essay, the power plant has still not exploded, then its ongoing existence should be seen as a prolonged and perilous suspension. Its reactors sit dormant but dangerous; its systems operate not through resilience, but through patchwork improvisation under siege.

You’re reading this essay for free. With a membership, you can read the full magazine, and you get access to our fabulous Library.

Here’s our offer: 3 months unlimited digital access + 1 print edition for € 38,00 € 19,00

You’ll get Issue Eleven in print as your first magazine, right to your mailbox.

- The Convention on Early Notification of a Nuclear Accident was signed in September 1986; the Convention on Assistance in the Case of a Nuclear Accident or Radiological Emergency took effect in February 1987. ↩︎

- See IAEA, « Nuclear Safety, Security and Safeguards in Ukraine, February 2022–February 2023 ». ↩︎

- Per Högselius and Achim Klüppelberg, The Soviet Nuclear Archipelago: A Historical Geography of Atomic-Powered Communism (Central European University Press, 2024). ↩︎

- Scott Kaufman, The Environment and International History (Bloomsbury, 2018); Serhii Plokhy, Chernobyl: History of a Tragedy (Penguin, 2018). ↩︎

- Popular lore has it that French officials proclaimed that « the Chornobyl cloud has stopped at the French border »; in fact they didn’t use that phrase, but there was no shortage of misleading reassurance. ↩︎

- See Dolores L. Augustine, Taking on Technocracy: Nuclear power in Germany, 1945 to the Present (Berghahn Books, 2018); Stephen Milder, Greening Democracy: The AntiNuclear Movement and Political Environmentalism in West Germany and Beyond, 1968-1983 (Cambridge University Press, 2017); Tomasz Borewicz, Kacper Szulecki and Janusz Waluszko, The Chernobyl Effect: Antinuclear Protests and the Molding of Polish Democracy, 1986-1990 (Berghahn Books, 2022). ↩︎

- Ulrich Beck, The Metamorphosis of the World: How Climate Change is Transforming our Concept of the World (Polity, 2016). ↩︎

- See Craig Daigle, « The Era of Détente », in The Routledge Handbook of the Cold War, edited by Artemy M. Kalinovsky and Craig Daigle (Routledge, 2014). ↩︎

- The Doomsday Clock ticked in the background of the music video for Sting’s « Russians » (1985), an affecting expression of the long, grey period of détente. « There is no such thing as a winnable war, » the lyrics aver, « We share the same biology regardless of ideology, but what might save us, me and you, is if the Russians love their children too ». The song was an adaptation of Sergei Prokofiev’s Lieutenant Kijé suite (1934), composed for the Soviet film of the same name. Set in St. Petersburg at the turn of the nineteenth century, the plot centers on a nonexistent officer whose name is mistakenly entered into military records. Too embarrassed to admit the clerical error, officials fabricate an entire biography for Kijé. When the emperor finally demands to meet this loyal servant, they claim Kijé has died heroically in battle, and the emperor commends the brave officer who never existed. One could take from this tale the lesson — complete with empty coffin — that our Cold War eschatology was always more Kijé than Kennedy: a fiction of control when there was none. ↩︎

- Timothy M. Lenton et al, « Tipping Elements in the Earth’s Climate System », Proceedings of the National Academy of Science 105:6 (2008), 1786-93. ↩︎

- Kevin Anderson, « Climate Change: Going beyond Dangerous – Brutal Numbers and Tenuous Hope », What Next, Volume III (September 2012). ↩︎

- Anna Tsing, The Mushroom at the End of the World (Princeton, 2015). ↩︎

- Donna J. Haraway, Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene (Duke, 2016). ↩︎

- Jem Bendell and Rupert Read, eds., Deep Adaptation: Navigating the Realities of Climate Chaos (Polity, 2021). ↩︎

- See Alexander Etkind, Russia Against Modernity (Polity, 2023). ↩︎