〖 Found in translation 〗

Found in translation

Found in translation

The reader will find, seeded throughout Issue Three, some translation tales from writers in Arabic, German, Hungarian, Romanian, Spanish, Swedish and Turkish, finding their way into German, Greek, Italian, Serbian, English and more. These tales can be filed with (also in this issue) Oksana Forostyna’s parsing of « untranslatable » Ukrainian humor and with Alexander Wells’s defense of Denglisch (and Berlinglisch, and Globish).

Translation, as a topic, tends to invite polemic or lamentation. Does the ERB have a stance? Not really. Our premise is that translation finds as much as it loses. The ERB’s editorial assistants, Nienke Groskamp and Job Wester, asked nine writers not what was lost but what was found in translation, as a text is given new surfaces and new depths. What’s the rightest or wrongest or closest or strangest thing that a reader has found in a new language? What’s something you wish would be found?

An inquiry into varieties of translational experience became a series of reflections on artful error and unexpected intimacy.

☞ Mona Kareem: « Bidoon » ➞ « Bedouin »

☞ Carlos Fonseca: « Para Ati » ➞ « Para ti »

☞ Agnes Lidbeck: Why are you so cold-hearted?

☞ Defne Suman: Borrowed time is borrowed money

☞ Hans von Trotha: Judge a book by its covers

☞ Iman Mersal: Panties of the people

☞ Krisztina Tóth: « droid » ➞ « druid »

☞ Lavinia Braniște: Overalls & eyeglasses

☞ Lydia Sandgren: Read between the stripes

We asked nine writers not what was lost but what was found in translation, as a text is given new surfaces and new depths. What’s the rightest or wrongest or closest or strangest thing that a reader of yours has found in a new language? What’s something you wish would be found?

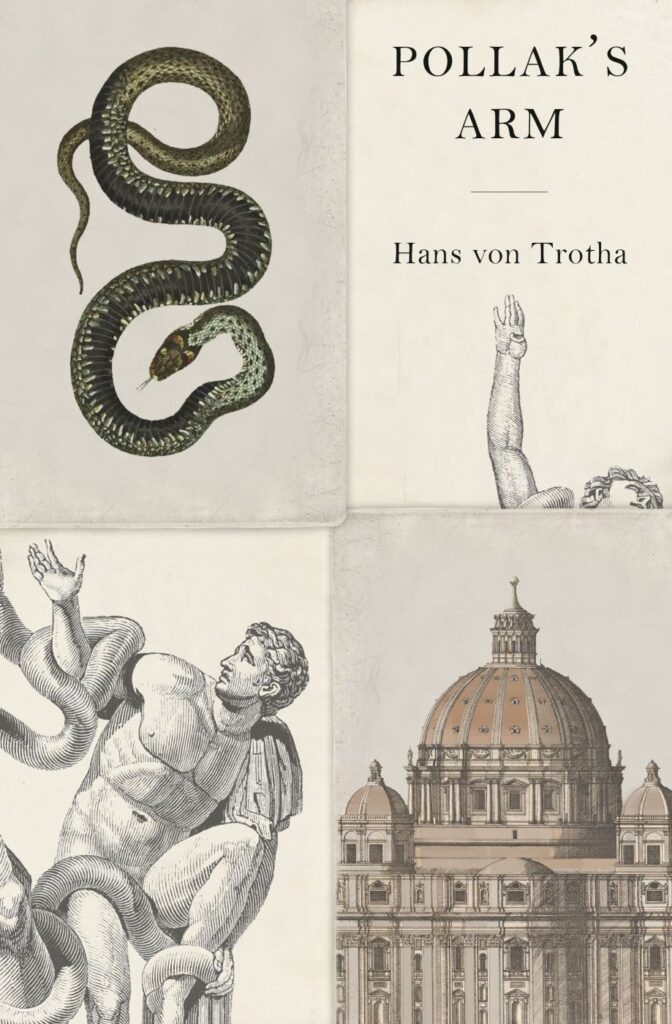

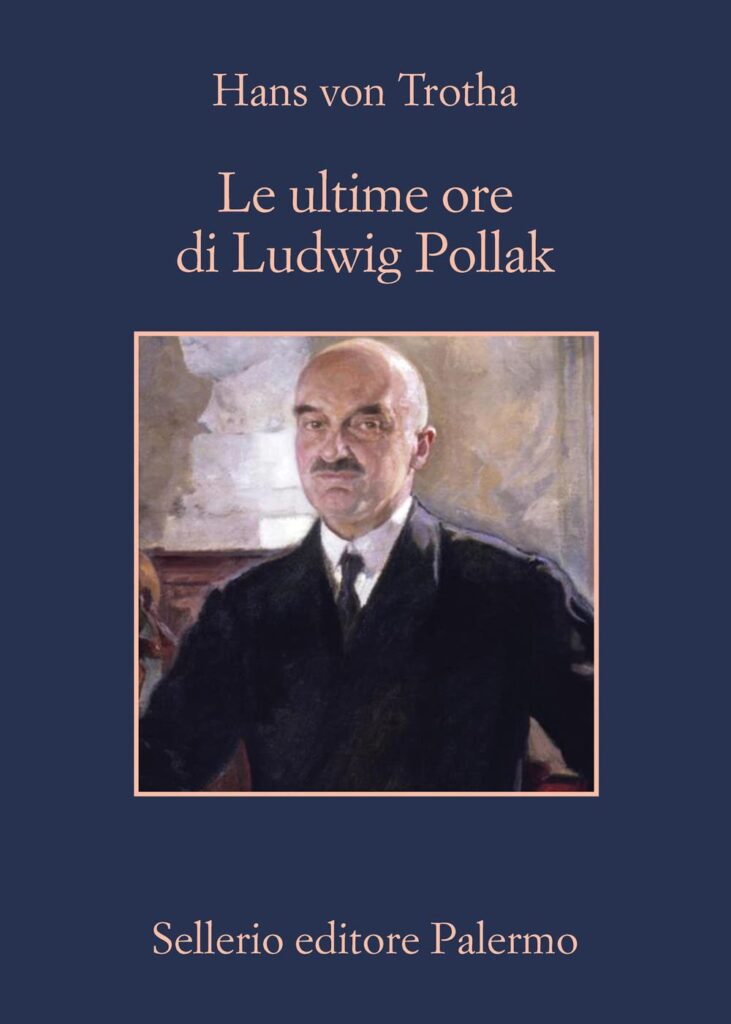

The German original of my novel Pollak’s Arm, the American translation and the Italian version: they look like three completely different books and they also present the story in a very different way. The Italian publisher even changed the title, because Pollak’s Arm was thought to be too enigmatic. At first I was annoyed about the American cover, because I come from a very academic tradition and it looks almost like the cover of a comic. But the task of cover art is to hold your attention for more than three seconds, and I now think the cover tells and sells a very intelligent and intriguing small story.

Pollak’s Arm is about the Jewish archaeologist Ludwig Pollak, an art dealer who got famous for finding the lost marble arm of the statue of Laocoön that stands in the Vatican. In October 1943, he, his wife, and his two adult children were sent to Auschwitz, where they all died. The book can be read as an art-historical novel, as an exploration of an archaeological issue or as Holocaust literature. In Germany it’s read as the latter, which is a problem, because there’s so much of that out there already. The Italian translation came with a blurb by a famous archaeologist on the cover, and there it’s seen as describing a chapter in art history. The American edition received the best reviews and acknowledgements, and I think that is because it’s read as both. There are so many layers and secrets hidden in the text, and American readers found them all. That was very touching.

In April 2022, Ingrid D. Rowland reviewed my book in the New York Review of Books and made a link to the war in Ukraine. She said the book was important, because it explains how a civilization that believes in art and culture could be convinced that barbarism does not exist. This is the reason the protagonist doesn’t flee — he can’t imagine such barbarism. She very aptly added that it’s the same for us now: we couldn’t imagine that barbarism still exists, and now we suffer the consequences.

Hans von Trotha is a German historian and author. His novel Pollak’s Arm (2021) was translated by Elisabeth Lauffer and published in English by New Vessel Press. Spanish and Turkish translations are forthcoming.