Aarhus City Hall, 1941

Architect: Arne Jacobsen

Back to the office:

A series

STEPHAN PETERMANN, RUTH BAUMEISTER & MARIEKE VAN DEN HEUVEL

As people are returning to their offices, so is the blah-blah-blah about office space optimization. Stripped, rethought, and renewed: the office of the future!

But what can be learned from the office of the past? Stephan Petermann, Ruth Baumeister and Marieke van den Heuvel wondered what endures. They’ve researched landmark office buildings that still function as offices today, studying archival documents, photography past and present, contemporary interviews and criticism, and compiled their findings in their bulky book, Back to the office: 50 revolutionary office buildings and how they sustained. They bring us to four of these locations:

The Reliance Building is a revolutionary pigeon haven (Chicago, USA)

Aarhus City Hall is a Gesamtkunstwerk (Aarhus, Denmark)

The Shizuoka Press and Broadcasting Center is a Metabolist pearl (Tokyo, Japan)

The Van Leer headquarters is not a « troubling fish tank » (Aalsmeer, Netherlands)

Aarhus City Hall. Photo on the right by Jens Frederiksen.

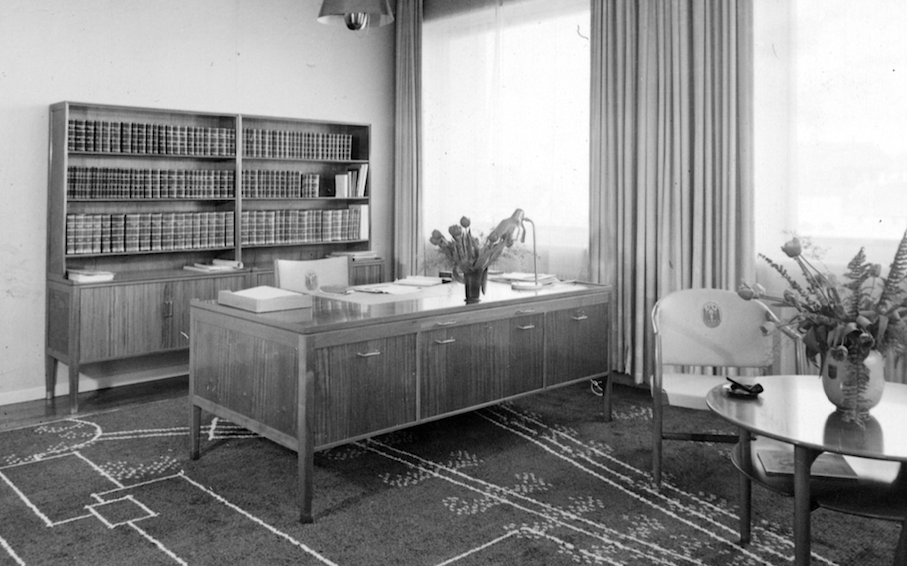

The design of Aarhus City Hall, which initially divided the Danish nation, today is considered one of the highlights of Scandinavian Modernism: a Gesamtkunstwerk in which everything — from the urban scale of the building to the interiors, the uniforms and briefcases of some of the personnel, as well as the lamps, ashtrays, coat hangers, and stamps — was subject to design. For the furniture design, Jacobsen and Møller hired the young cabinet maker and then-recent design graduate Hans Wegner, who became one of the most successful Danish furniture designers worldwide. Due to their comfort, timeless aesthetics, and the quality of the craftsmanship, much of the furniture is still in use, almost eighty years after the building’s inauguration (an impressive sustainability credential).

A glance at the mayor’s office today speaks for itself: « The cigar box has been removed and the bitters hidden from sight, if they are there at all, » is how an architect recently described the almost untouched spatial setup of the room. Besides the repairs due to the war damage, there have been no major large-scale renovations since the building’s inauguration in 1941. Contemporary additions such as accessibility ramps, a smoke detection system, CCTV, and coffee kiosks, have had minimal impact. Occasionally, single office windows and worn-out pieces of linoleum or wooden flooring or stairs have been replaced. Invisibility is the goal.

Inside City Hall, then and now. Photo on the right by Jens Frederiksen.

But the building’s ability to sustain has been enabled by factors beyond architecture: the owner — who also happens to be the user — has not changed since 1937. Moreover, the owner/user also maintains the building. Craftspeople and facility management are in-house and a committee of representatives from all departments of City Hall collectively agree on changes or adaptations, which are then forwarded to the architect-in-charge. Those who complain about the draft in their office are reminded that they inhabit a landmarked building and are advised to bring an additional sweater.

The other buildings in this series:

The Reliance Building is a revolutionary pigeon haven (Chicago, USA)

The Shizuoka Press and Broadcasting Center is a Metabolist pearl (Tokyo, Japan)

The Van Leer headquarters is an admirably troubling fish tank (Aalsmeer, Netherlands)