published in Issue Four

Somehow this fever dream of eighteenth-century beauty helped me see the worst parts of our life online.

White waterlily (Nymphaea alba L.): leaf, flowers, fruit and seed. Colored etching by M. Bouchard, 1777.

A famous doctor reporting a man’s death from a venomous duck bite. A man living inside a silk bag for months recording his bodily inputs and outputs. A naturalist putting his young servant into a hot oven to observe the effects of extreme heat. A famous scientist studying how the environment affected the smell of his farts. A theory of the relationship between acute illness and haircuts.

As a historian of the Enlightenment, I find oddities like this frequently, not just deep in the archives or in obscure periodicals, but in some of the most popular and respected books of eighteenth-century European history. Some are ghastly, some are silly. Often, they feel curiously private, like personalized reminders of the foreignness of the past. They prove difficult to assimilate into what I know of the Enlightenment. I save them in a file on my computer with the hope that one day I’ll be able to make sense of them, to use them, somehow, in my writing. But mostly I hold onto them because they remind me that no matter how receptive to weirdness I may be as a scholar, there are always surprises, always a venomous duck, silk bag, or tortured servant that just moments before was beyond my imagining.

These kinds of oddities defamiliarize the past, but rarely do I experience them as illuminating something of our world today. Then recently while reading a French journal of the 1750s — Journal oeconomique of August, 1754 — I came across (amongst reports of German bee cultivation, Dutch epidemics and methods for improving French wool) an anonymous letter to the editor reporting a recipe for eau de pigeon. It’s a wild recipe with lots of ingredients. I’d never seen anything like it, but it also felt familiar in a way that I couldn’t quite place:

Take an ounce of each: the juice of water lilies, broad beans, melon, serpentine cucumber, and lemon. Add a handful of white bryony, wild chicory, lilies, borage flowers, and broad bean flowers. Then take seven or eight white pigeons, from which you will remove all the feathers, the tips of the wings, and the head; mince them well and put them with the previous ingredients in a still. Add to this mixture four ounces of crushed royal sugar, a dram of borax, and the same amount of camphor, the crumb of three small white breads fresh from the oven, and half a pint of good white wine. Let all of these materials digest in the still for seventeen or eighteen days, after which distill the whole thing, and reserve the water to use as necessary.

This pigeon water looked to be some kind of cosmetic, and was said to come from Denmark. In the letter, claims were made for its positive impact on the complexion: it could freshen the skin and return a youthful appearance. As I reread the recipe for clues on why people of the time would want to splash their face with the distilled essence of heavily-herbed pigeon meat, I kept repeating the phrase to myself. Pigeon water. Pigeon water.

The recipe seemed legitimate and well-intentioned even though the journal did not usually include beauty tips or instructions for making cosmetic concoctions. The Journal oeconomique, ou mémoires, notes et avis sur l’Agriculture, les Arts, le Commerce, & tout ce qui peut avoir rapports à la santé, ainsi qu’à la conservation & a l’augmentation des Biens des Familles, etc., to use its long solemn title, did not publish satirical essays by the likes of Voltaire or Jonathan Swift. There was little esprit or play in its prose. It was a venue for reforming ministers of state, high minded philosophers and zealous agricultural improvers to learn and share ideas. Its editors envisioned a better future through the breeding of vegetables, the study of diseases and the refining of economic ideas.

Since my knowledge of historical meat-based cosmetics lags behind my understanding of the philosophical and scientific ideas of the Enlightenment, I wanted to read more about the history of makeup and beauty advice. Turning away from the pages of the Journal oeconomique, my online research took me down rabbit holes to some very obscure websites. A few other people had rediscovered pigeon water and similar curious cosmetic recipes, but most of the information on these websites seemed wrong or misleading. Historical context was mostly absent or incorrect. Pages seemed to copy one another, distorting and sensationalizing as they went along — it seemed like some hyper-niche online echochamber. I stumbled upon unsourced blogs from amateur historians of cosmetics, promotional material from industrial trade groups posing as news, posts from little known fashion magazines, lots of automatically generated beauty content and a whole world of eighteenth-century dress-up for adults. Within thirty minutes, I found myself reading an excerpt from The American Duchess Guide to 18th Century Beauty: 40 Projects for Period-Accurate Hairstyles, Makeup, and Accessories.

The further I was pulled away from the earnest Enlightenment journal, the more that pigeon water began to feel like a dark mirror. Somehow this fever dream of eighteenth-century beauty helped me see the worst parts of our life online. The misinformation, the promise of something better, the seemingly random combination of many ingredients, the sensational claims, the violent dismemberment, the fermentation.

I'd long ago given up on Facebook and chose not to use Instagram. TikTok wasn't meant for me, but it found me when videos of disgusting food recipes began to be posted cross-platform on Twitter. This was not food as I was used to it. The videos veered away from presenting recipes you’d want to make. They employed unnecessary hacks, unsavory combinations and stunt ingredients. They also exhibited a number of their own genre conventions, orbiting new centers of gravity.

First, I noticed the ooze. Cheese is often included in these videos, in order to explore the visual, gustatory and sexual dimensions of gooeyness. TikTok creators love cheese. They use a lot of cheese. There is too much. It appears in foods that have no need for cheese or any other goo. There are also many, many full sticks of butter.

If there is no cheese or butter involved, other things ooze. Runny egg yolks, creamy sauces, syrupy toppings. Spaghetti can be included for convenience or hyper-redundancy; in a peak moment for the micro-genre, an influencer ground up dried spaghetti in a blender to make the dough for a « fresh pasta ». Other forms of pasta are also popular. Many forms of macaroni casserole make an appearance.

If no oozing or pasta-based ingredients are involved, then excessive amounts of ground meat should be. Preferably all of these ingredients should be included, possibly along with common convenience items like taco seasoning or corn chips. Since many of these videos originated in the United States, its junk food and snacks often find their way into the meals in unexpected ways. Doritos bags have become a vessel for food preparation.

Chefs are generally not involved in these videos. The dishes are made by people with no special knowledge or interest in food. Attention of viewers, not tastiness is key. Some of them are made by well-established influencers, some by copycats trying to get in on the game, and many now appear from content farms that pump out as many iterations of recipes as they can think of. All of these producers are hungry for views and clicks and comments and reposts, which means: money. Creating novel culinary abominations to get attention is the purpose of the genre. Hence, ramen pizza.

Historians in the future looking back on these videos would understand that stunt cooking videos have existed for a while, but that culinary rage baiting and treat-based trolling gained new visibility and popularity in 2022. That year, there was a wave of new videos of unnecessary preparation hacks. Frozen chicken breasts were grated. Meals were made from potato chips. Raw eggs were frozen in ice-cube trays. Odd food combinations proliferated. Chicken parmesan sushi. Cream cheese pasta. French toast tacos. A seven-pound sheet-pan hamburger seasoned with salsa and wrapped in tortillas. Performance art pioneers and teenagers joined moonlighting comedians and out-of-work magicians. Content farms followed. Mayonnaise was pan fried. Instant noodles were cooked in chocolate milk. Kebabs rolled in crushed candy.

Borage (Borago officinalis L.): flowering stem. Colored etching by M. Bouchard, 1774.

These disgusting food preparation videos have sent out reverberations across the internet, ripples in the pigeon water. In addition to the videos themselves ending up on other platforms, they spawned commentary videos, recipe reaction accounts and endless articles on websites that link to one another. Some reaction accounts have over three million followers, while long chains of commentary articles referring to one another can be traced thanks to the generous hyperlinking needed for search engine optimization. When the videos started appearing on Twitter, the middle-aged crowd was not ready for this new type of shitposting. There was outrage, food traditions of various cultural heritages were defended, disgustingness called out. They took the bait and regurgitated it as new angry content. Another gulp of pigeon water.

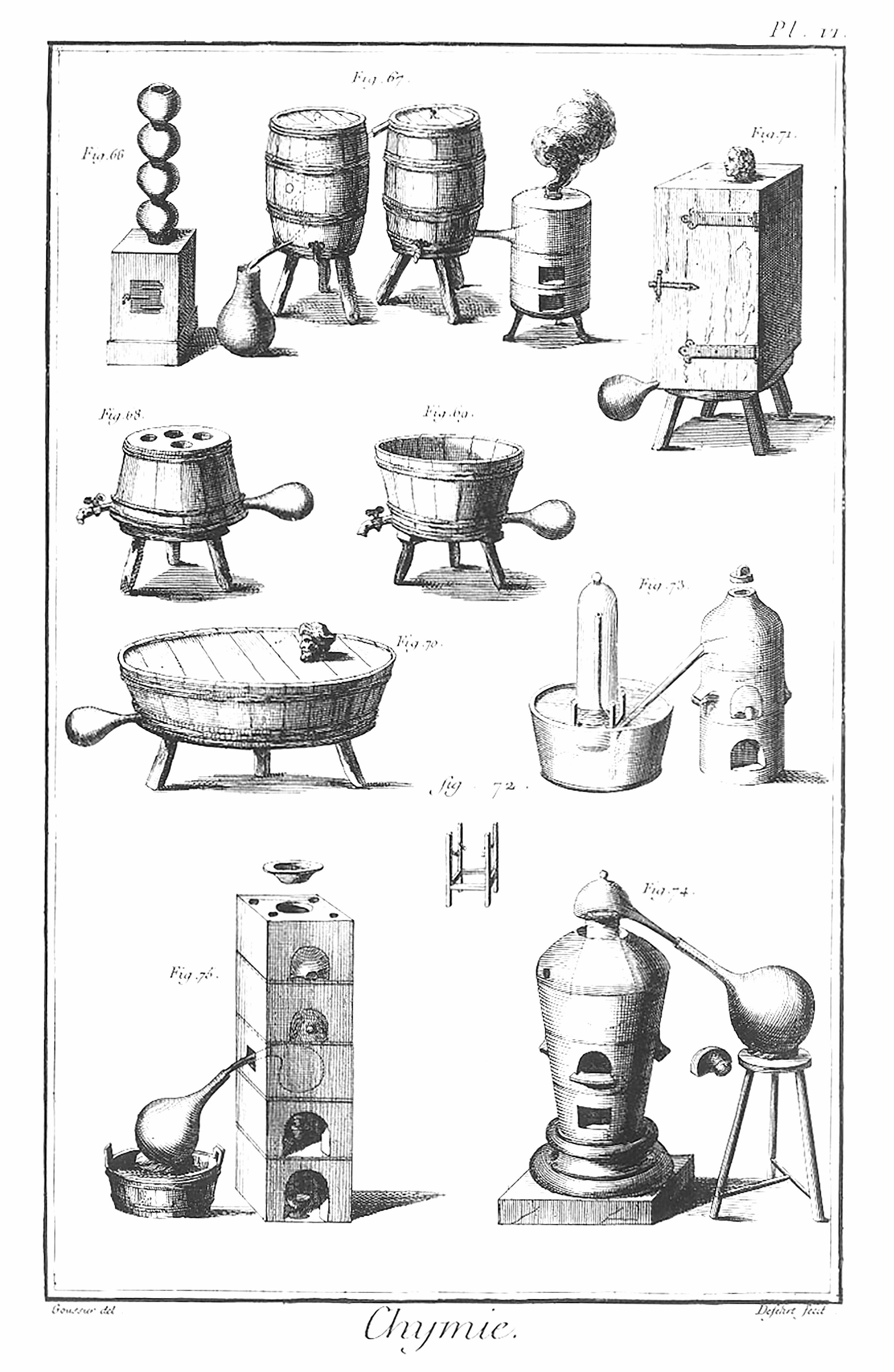

Chemistry from Encyclopédie, ou dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers. Wellcome collection.

Watching these videos, I began to feel like the Enlightenment naturalists I often study. I began categorizing and making a taxonomy of this odd pocket within social media. The subgenre of these videos that’s purely meant to generate outrage, can be further divided up between American Midwestern wholesomeness, stereotypical twenty-something influencing, teenage gross out and attractive homogenous condo cooking. This latter group of videos is my favorite. They mostly feature hosts who seem to be chosen because they are attractive in a bland way and demonstrate little personality — sometimes two of them appear, why not — working in similarly clean, new kitchens. The cooking space is as mildly attractive as the hosts, just appealing enough to get the attention while not attractive enough to be distracting. The food is still often disgusting and odd — the bland beauty uncannily heightening the terribleness of the recipes. These videos speak of a world of bright white quartz counters tops, shining stainless steel ovens, large sheet pans and casserole containers, as if every new condo unit were first used to vomit food-like creations online.

These creations remind me of the first time, four or five years ago, I noticed the banner ads for T-shirts that did not seem to be the product of human design. Weird enlarged pictures that no one was likely to want, covering the entirety of their chest and stomach. A baby’s belly. A sponge. Strange phrases in ugly fonts. A concrete municipal water tower. It was like a computer had been set to work on creating random combinations of picture and shirt. If enough people choose to purchase one of these monstrosities, they would be produced in a small batch, or maybe the operation was automated and each purchased shirt was made to order. With complete disregard for taste or style or tradition, the algorithms tried to find and exploit previously unrecognized niches. The logic of capitalism, supercharged. I can only imagine the food recipes that will be created once AI gets in the game.

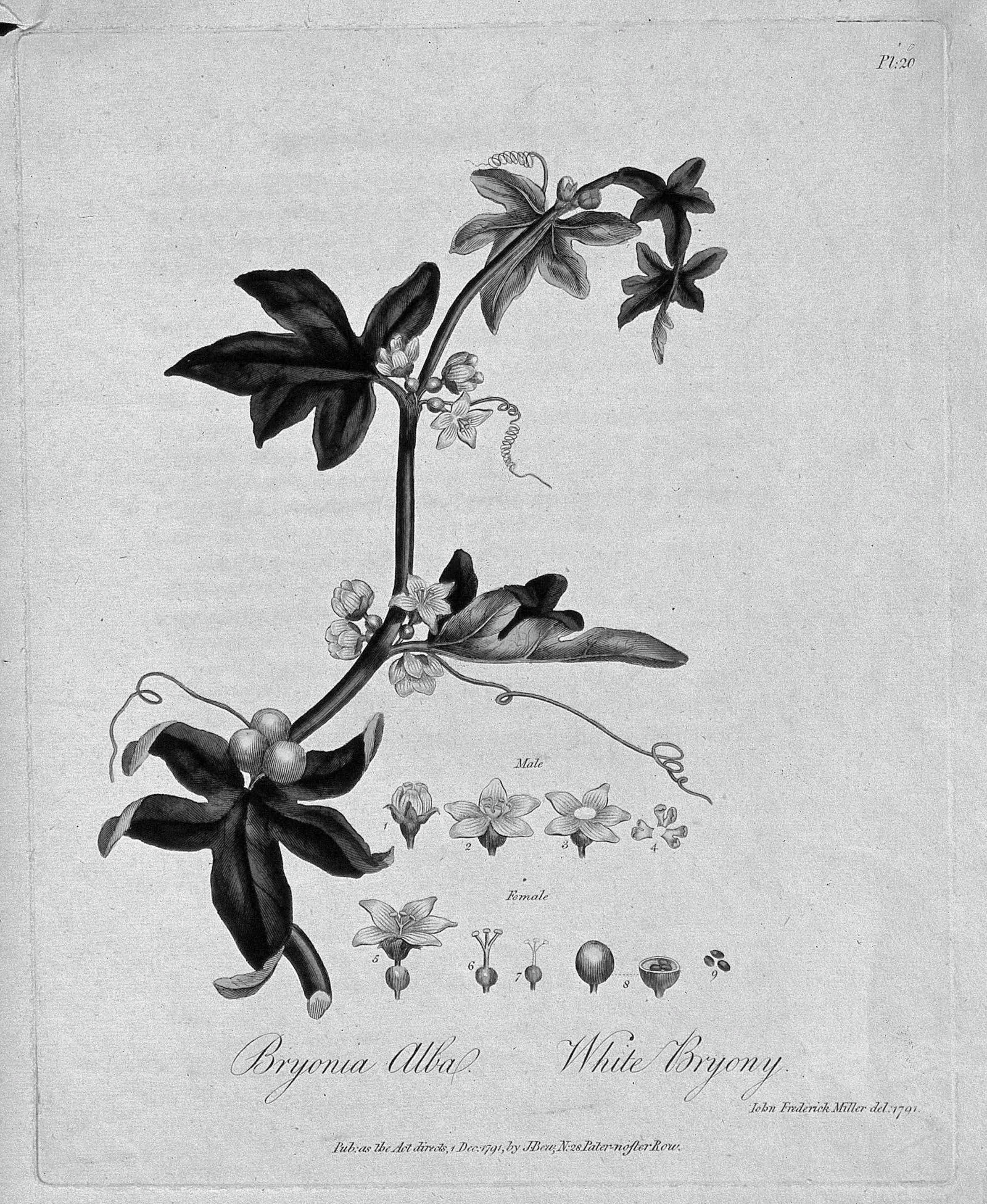

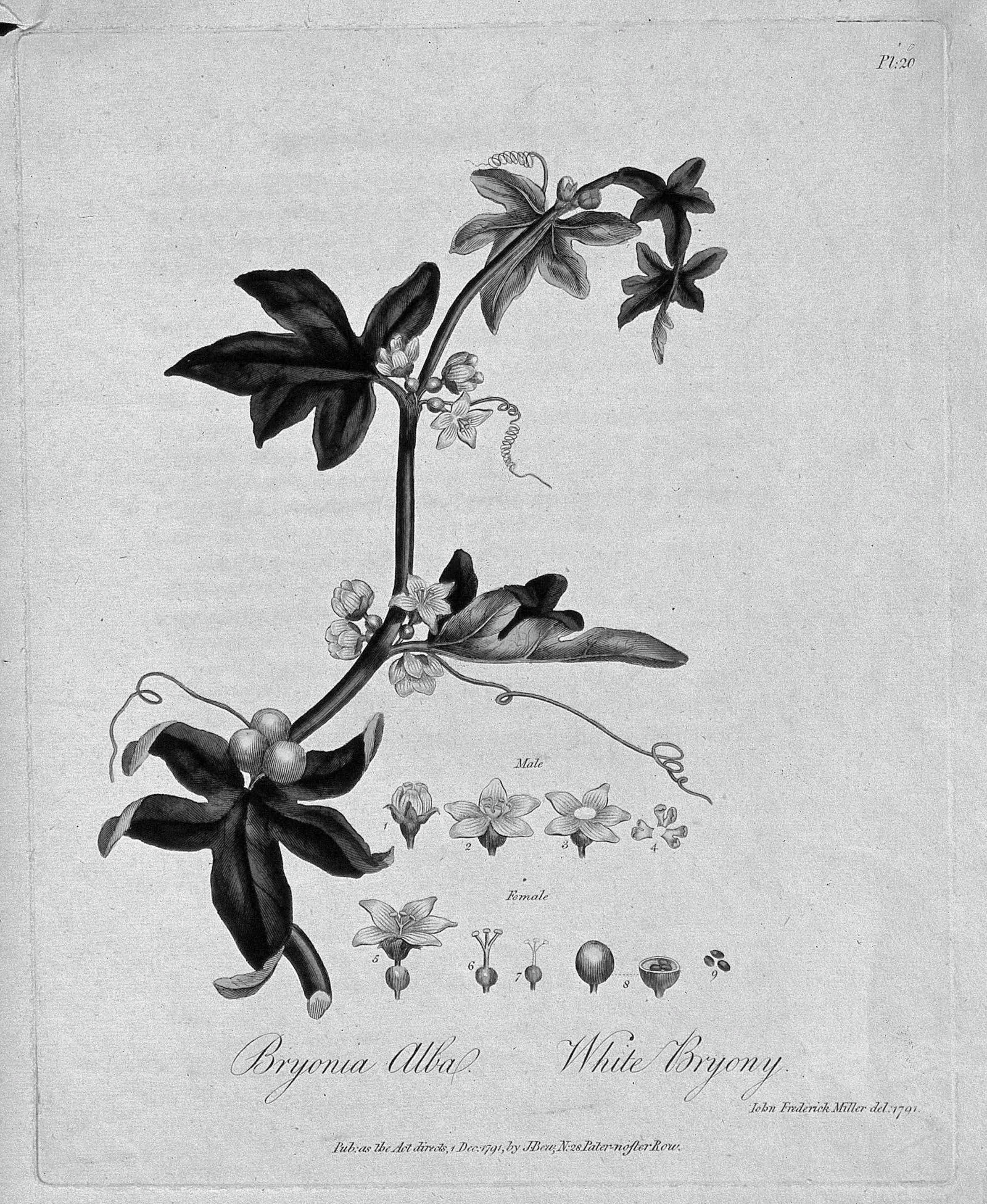

White bryony (Bryonia dioica): flowering and fruiting stem with floral segments. Colored etching after J. Miller, 1791.

There’s a principle of plenitude that most eighteenth-century philosophers professed: everything that can be, is. What was once a metaphysical conviction about the natural world is now a rule of hyper-capitalism. Every niche must be filled, every opportunity for revenue exploited, every bat-shit-crazy idea blurted out in text or video. Everything that can be imagined must be made into a short, jumpy video.

Rage-baiting food recipe videos are probably a blip in the history of the internet. They will be replaced by some other equally niche phenomenon — they may even be technofossils by the time this essay is read. But there will be many more pigeon water recipes produced, filmed, posted, cross-posted, commented upon and raged against. Online pigeon water is what we swim in and slather on ourselves. It’s what oozes out of our social media apps. It’s clickbait and fake news. It’s the comments section and the twittersphere. It’s banner ads and branded content. Reaction accounts and unboxing videos. It has no end or limit. It flows everywhere, drenches everything. Or at least that’s what it feels like sometimes. Pigeon water on our faces and in our brains, reminding us why the internet gave new life to the old term « hellscape ».

It’s almost enough to send me into the fields to forage for wild chicory and borage flowers.

Rock Dove, Rock Pigeon. White Barb/Mahomet, by Peter Paillou, 1744. Taylor White Collection, McGill Library, Montreal, Quebec.

White waterlily (Nymphaea alba L.): leaf, flowers, fruit and seed. Colored etching by M. Bouchard, 1777. Wellcome collection.

Borage (Borago officinalis L.): flowering stem. Colored etching by M. Bouchard, 1774. Wellcome collection.

White bryony (Bryonia dioica): flowering and fruiting stem with floral segments. Colored etching after J. Miller, 1791. Wellcome collection.