On Arnold, action cinema & Übermenschlichkeit

The first movie Arnold Schwarzenegger remembers seeing was a Tarzan film, starring the athlete-turned-actor Johnny Weissmuller. For reasons that will become clear, I like to imagine that it was Tarzan Finds a Son! (1939). Weissmuller, born Johann Peter Weißmüller in a now-Romanian corner of the Austro-Hungarian empire, was brought as an infant to America in 1905, and was an Olympic swimmer before swinging from trees on a screen — a model for Arnold’s own path, though Arnold migrated as a fully-formed and at least subculturally famous « Mr. Universe », the bodybuilding pageant he won in 1967.

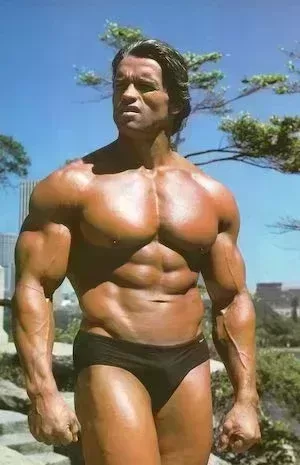

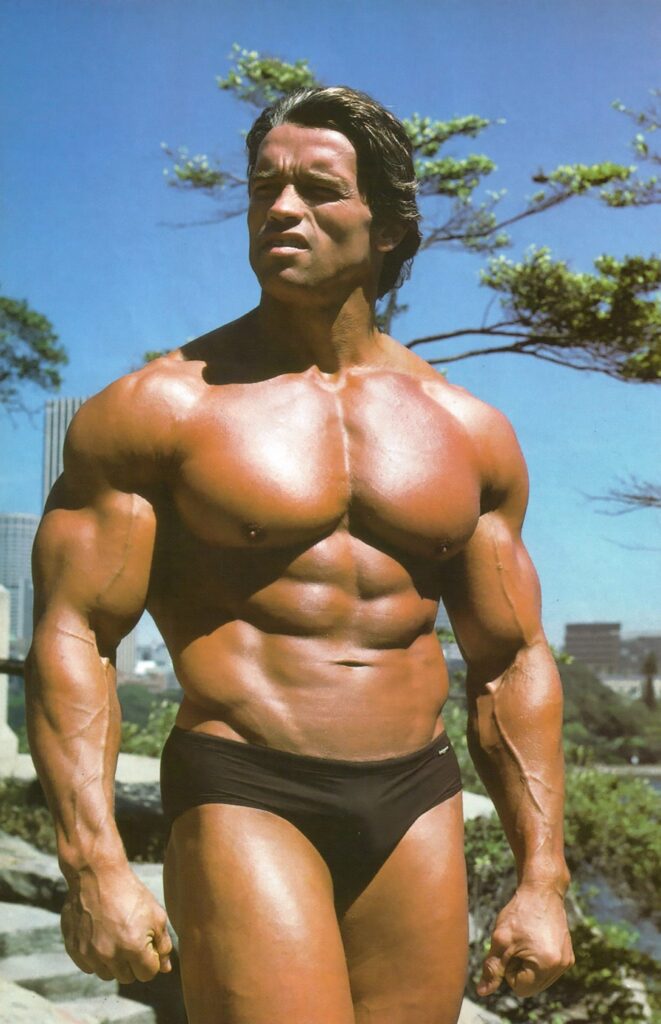

Born in Thal, a village outside of Graz, Austria, in July 1947 — a Leo, obviously — Schwarzenegger arrived in America in 1968, twenty-one years old at the peak of « the Sixties ». But Arnold’s Sixties weren’t the Woodstock Sixties, nor a Sixties of generational political strife; they were the Sixties of Gold’s Gym on Venice Beach in LA, and of the world around it. Steroids, marijuana, transcendental meditation. From the subculture of bodybuilding, Schwarzenegger would spring to the mass culture of Hollywood. He never really had to be a struggling actor because he’d also become a landlord, scaling up from the six-unit apartment building he first bought, to ever-larger commercial real estate (he was always entrepreneurial, self-pumped and self-made). Or rather, his struggles as an actor weren’t financial but linguistic and, counterintuitively, physical, insofar as his body made him a freakish curiosity. It makes sense, therefore, that his first starring role was as an otherworldly god, and that his voice had to be dubbed.

Hercules in New York (1970) casts Arnold as a restless Hercules who, after an argument with his father Zeus, ditches Olympus for semi-divine escapades in the big city of puny mortals. Not a great movie, alas, but it does inaugurate a key Schwarzeneggerian motif: the naïve straight man paired with a comic Jew. Hercules arrives by ship, sees the Statue of Liberty, defeats some dock workers in a slapstick brawl, and meets Pretzie, the street-smart, wise-cracking pretzel-seller who will shepherd him around. Played by the Jewish comedian Arnold Stang, Pretzie is this movie’s answer to Dustin Hoffman’s more tragic Ratso/Rizzo in Midnight Cowboy (1969), a film which Hercules in New York faintly resembles.

Few have watched Hercules in New York to the end: Zeus decides to come to New York himself, but he does so in the form of a flying rabbi. It’s an in-joke about Hollywood, the celluloid melting pot from which Jewish-immigrants-turned-Americans churned out hard-boiled Westerns, utopian screwballs, liberal melodramas and everything else for a consuming world. It’s a fitting irony that Arnold’s first Hollywood role required him to Americanize his foreign name, like so many other assimilated exotics: he is credited as « Arnold Strong ». By the time he played the bit part of « Handsome Stranger » in the forgettable Western satire The Villain (1979), starring Kirk Douglas (né Issur Danielovitch), Schwarzenegger was credited as himself.

There are many reasons Arnold Schwarzenegger invites cultural, political and historical inquiry (Schwarzeneggerology). He has, for example, embodied the international cliché of the American Dream more fully and more famously than anyone else: the immigrant from a pre-modern European nowhere, who became the most famous bodybuilder of all time. (Aesthetic inquiry, too: Andy Warhol photographed him, and he was exhibited at the Whitney Museum in 1976, in Articulate Muscle: The Body as Art.) He became the world’s most famous action hero, and then the « Governator » of California in 2003. And he would seem to embody, again more perfectly than anyone else, the American Century and its obsolescence, for neither Arnold nor America can stave off the inevitable. Those « American » arcs are good ones to start with, but a full Schwarzeneggerology will demand other arcs: from body to commodity, from action to comedy, from Mensch to Übermensch — and back.

All of Schwarzenegger’s movie roles bear some relation, overt or veiled, to Schwarzenegger the actual human being; Hercules in New York is no exception. In Schwarzenegger’s autobiography, written in 2012, the Pretzie-figure who picks up immigrant Arnold from the airport is the bodybuilding photographer Artie Zeller, and they will become fast friends. Schwarzenegger describes him with affectionate perplexity:

Artie fascinated me. He was very, very smart, yet he had absolutely no ambition. He didn’t like stress, and he didn’t like risk. He worked behind the window in the post office. He came from Brooklyn, where his father was an important cantor in the Jewish community; a very erudite guy.

For Arnold the new immigrant, Artie the more experienced son of immigrants is modernity’s upperclassman, having achieved a paradoxical anchoredness, his own uprootedness having matured into an identity and an orientation to the world:

Artie went his own way, getting into bodybuilding in Coney Island. … He was fascinating because he was self-taught, endlessly reading and absorbing things. Besides being a natural with languages, he was a walking encyclopedia and an expert chess player. He was a die-hard Democrat, liberal, and total atheist. Forget religion. To him, it was all bogus. There was no God, end of story.

It is Artie, tellingly, who serves in the autobiography as the foil for Arnold’s early commitment to the Republican Party.

Arnold arrived a mere month before the 1968 Presidential election, which faced Hubert Humphrey against Richard Nixon; Artie and his Swiss wife would translate the candidates’ speeches for him. Arnold’s stylized account emphasizes total naïveté, both linguistic and ideological. « Humphrey, the Democrat, was always going on about welfare and government programs, » he writes, « and I decided he sounded too Austrian. But Nixon’s talk about opportunity and enterprise sounded really American to me. » And then comes the commitment, wrapped in a punchline:

« What is his party called again? » I asked Artie.

« Republican. »

« Then I’m a Republican, » I said. Artie snorted, which he often did both because he had bad sinuses and because he found a lot in life to snort about.

And it’s Artie the charismatically jaded Jewish Democrat who will first introduce Arnold the ingénu to the personage of Ronald Reagan. Schwarzenegger happens to buy a « cool black-and-white poster of a cowboy with two guns drawn » in Tijuana, for five bucks, and he « put it up on the wall with Scotch tape » — like the muscleman pictures he’d taped above his bed as a boy. Artie sees it and snorts, and then comes the perfectly apolitical foreshadowing of Schwarzenegger’s political future:

I said, « What’s the matter? »

« Oh, Reagan, I mean, Jesus. »

« That’s a great picture. I found it in Tijuana. »

He said, « Do you know who this is? »

« Well, it says below, ‘Ronald Reagan.’ »

« He’s the governor of the state of California. »

I said, « Really! That’s amazing. That’s twice as good. I have the governor of the state of California hanging here. »

« Yeah, he used to be in Westerns, » Artie said.

It’s all so innocent. By his own account, he’d fled a stultifying « socialist » country for the land of opportunity. From the beginning he was entrepreneurial — disciplined — but his discipline and entrepreneurialism were not driven by any bitter grievance against longhaired hippies. The New Left, meanwhile, was for Arnold both new and not new. To pick an example from his slice of the counterculture, he found nothing remarkable or « liberating » about American women’s unshaved legs, since he’d found unshaved legs to be the European norm. Having left « Europe » behind, he could be naturally as libidinous as the counterculture and naturally as business-oriented as Nixon, without any turmoil of contradiction.

Conan the Barbarian (1982), Schwarzenegger’s first genuine star turn, marks another spectacular entrance into human time, albeit in a pulpy, pseudo-ancient, fantasy-adventure landscape. The plot, like most of the plots that Schwarzeneggerologists have to deal with, is not un-fun to summarize. As a child, Conan sees his mother brutally slayed by Thulsa Doom, played with hilarious gravity by James Earl Jones. Orphaned and enslaved, Conan is condemned to turn a giant wheel in a desolate landscape — a grain mill, apparently, but the function is irrelevant.1 Chained to his post, turning and turning, scrawny Conan grows into hulking brute Conan, who’s then conscripted into gladiatorial battle. « He did not care any more », the legend’s narrator intones. « Life and death: the same. Only that the crowd would be there to greet him with howls of lust and fury — he began to realize his sense of worth. He mattered. » After his victories in these bloody contests comes the learning of language, writing, poetry, sex (Conan becomes a human stallion, « bred to the finest stock »). Finally freed, his steely discipline endures through his many adventures, culminating in his revenge upon Thulsa Doom. « What’s best in life? » Conan is asked upon reaching fame as a gladiator. « To crush your enemies », he answers, « see them driven before you, and to hear the lamentations of their women. »

« Conan the Barbarian » was an anti-antiwar film, a counter‑countercultural fantasy

Appearing almost a decade after the ignominious American exit from Saigon, Conan the Barbarian was an anti-antiwar film, a counter-countercultural fantasy: Conan doesn’t dodge the draft, and when he rescues a princess from a cult, he kills the cult’s hippie-looking leader. The director, John Milius, occupied the surfer-anarchist-militia fringe of New Hollywood. He’d drafted Dirty Harry and written Apocalypse Now, among other gory autopsies of Americana.

For Schwarzenegger, though, the Vietnam War had been a distant abstraction. « If anybody had asked me, » he recalled in his autobiography — the implication being that nobody did ask him, or had any reason to — « I’d have been for the war. I’d have said, ‘Fucking Communists, I despise them.’ I grew up next door to Hungary, and we always lived under the threat of Communism. … So I felt very good that America was fighting Communism big-time. » But he was insulated from the draft — indeed had gotten out of his obligatory Austrian military service early — and he wasn’t a student.

…it is better to consider Conan as a late entry into the peplum genre…

Conan and the peplum genre

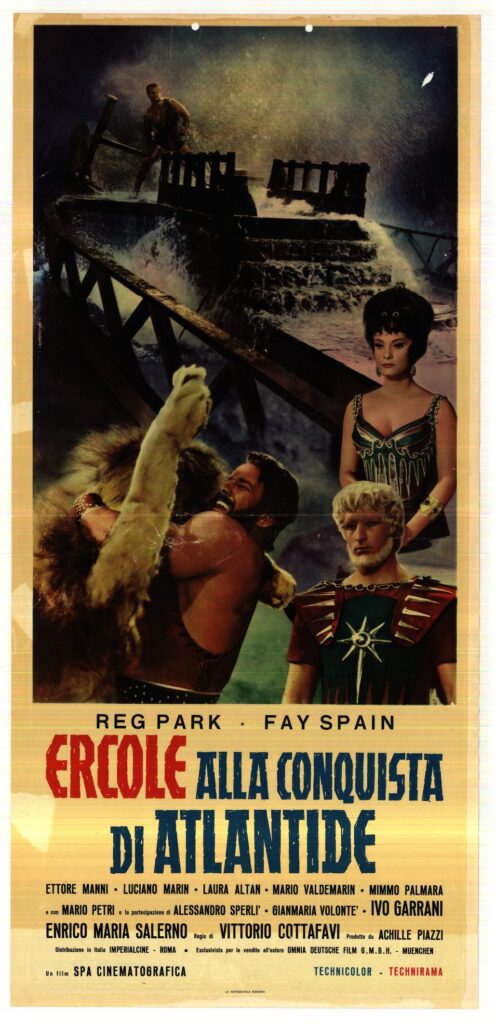

… it is better to consider Conan as a late entry into the peplum genre (from the Latin word for tunic), the sword-and-sandal epics of the sort that young Arnold saw in Thal, imported from Italy: Ercole alla conquista di Atlantide (Hercules and the Conquest of Atlantis, 1961), for instance, starred the English bodybuilder Reg Park, later Arnold’s mentor. …

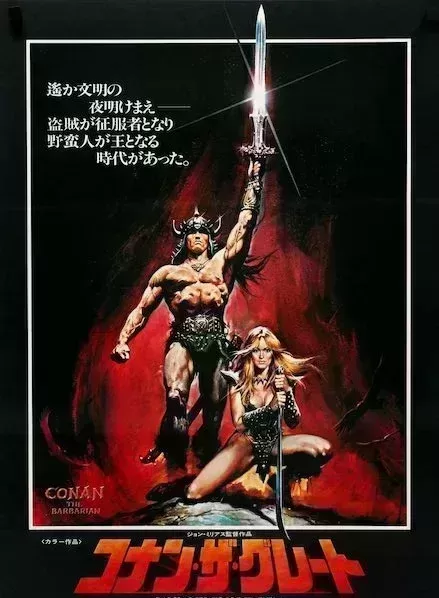

Japanese film poster for Conan the Barbarian, by Renato Casaro; Ercole alla conquista di Atlantide (1961)

For the purposes of Schwarzeneggerology, it is better to consider Conan as a late entry into the peplum genre (from the Latin word for tunic), the sword-and-sandal epics of the sort that young Arnold saw in Thal, imported from Italy: Ercole alla conquista di Atlantide (Hercules and the Conquest of Atlantis, 1961), for instance, starred the English bodybuilder Reg Park, later Arnold’s mentor.2

The film scholar Richard Dyer has best captured the workings of that genre, from its European pedigree forward. In their Italian heyday, from 1957 to 1965, peplum films thrived, Dyer observes, because they straddled contradictions both economic and ideological. In an era of internal migration and industrial boom, « The peplum celebrates a type of male body for an audience to whom [that body] had until now been a source of economic self-worth » — and it did so as the economic foundation of that self-worth was being shaped and reshaped, ongoingly crumbled and ongoingly reassembled. The peplum hero rescues helpless laborers from giant wheels; he defeats massive pre-modern war machines. « His triumph over the machine by body alone offers an audience a fantasy of triumph over their new conditions of labour in terms of their traditional resources. »3 He slays mythical beasts whose mechanical-ness is both masked and revealed by the era’s special effects.

Peplums were created and screened in the wake of Italian fascism, but before the films of the 1970s that would look more squarely at fascism. They may appear vaguely fascistic in their strongman theatrics, but for Dyer they represented « an imaginary working through of the shameful monstrousness of the [fascist] period, shameful because it was fascist or because [fascism] was defeated. » Their power lay in the ambivalence they registered.

Conan the Barbarian, a generation later, marks a turning of transatlantic screws. It was filmed in Spain because Spain’s film industry wasn’t unionized (unlike Italy’s, by then). « The choice was the same as always in modern movie production », union-skeptic Schwarzenegger would recall in his autobiography: « between countries with an established moviemaking industry and labor unions, like Italy, and entrepreneurial, nonunionized countries like Spain. » There were deeper cultural twists, too. The heroes of those Italian peplums — endearingly clunky, and far from Hollywood’s polish — were often American bodybuilders, playing semi-divinities in an era of American ascendancy. Conan, by contrast, arrived from Hollywood, and starred Arnold, the former Mr. Universe whose very Europeanness made him at once exotic and utterly at home in that fantasy world.

Come for James Earl Jones wearing green contact lenses and morphing into a giant snake. Stay for the moment that Arnold lumbers through a crowd and punches a camel in the face.

The 1980s and 90s were Schwarzenegger’s platinum age, in terms of body count and market share. He became the money-makingest star in the most expensive and spectacular movies then being made: the action film proper that flourished through Ronald Reagan’s presidency and into the post-Cold-War era of American unipolarity. Like any cultural icon, Schwarzenegger needed no introduction then (and it’s weirdly difficult to « introduce » him in an essay), because he was a hyper-familiar point of global reference, or a punchline in the collective joke (a joke he was in on), all of us knowing what it means to get to the chopper.

He was only the most muscular star in a constellation of greased-up leading men. Some tended to play wry everymen in the wrong place at the wrong time (Bruce Willis in Die Hard); some played white-working-class underdogs turned international freedom fighters, winning the wars that piss-ant pencil-pushers were too cowardly to win (Sylvester Stallone in the Rambo sequels); some played suicidal cops who derived medieval satisfaction from electrical torture (Mel Gibson in Lethal Weapon). These were the Hard Bodies of the literature and media scholar Susan Jeffords’s study of masculinity in the Reagan era, written during the platinum age itself.4

Schwarzenegger stood at the top of this heap, 5but he was always noticeably other. Unlike, say, Rocky or Rambo, we never really see an Arnold character climb the steps to Apollonian physicality; he arrives, if the phrase will be forgiven, always already pumped, immer schon aufgepumpt. Often his accent placed his characters on some vague international fringe of the military-industrial complex, a black ops isolato. Commando (1985), the stupidest Schwarzenegger movie, sends Arnold as « John Matrix », a special-forces-something-or-other, to slaughter a cartel in the fictional Latin American country of « Val Verde » (and to rescue a daughter he somehow also has?). Predator (1987), the purest Schwarzenegger movie, sends Arnold as Alan « Dutch » Schaefer, a paramilitary-something-or-other, into the jungle for a Melvillean confrontation with opaque evil, and he alone will survive the wreck.

Arnold was action cinema’s Adamic man, alternately entering and exiting normal human time.

We could push the point further: that otherness allowed Arnold to inhabit a deeper and paradoxically more « American » mythology: the American Adam that the literary scholar R.W.B. Lewis, in a classic study from 1955, saw permuting through canonical American literature, from Ralph Waldo Emerson forward: « a figure of heroic innocence and vast potentialities, poised at the start of a new history. » Arnold was action cinema’s Adamic man, alternately entering and exiting normal human time, « emancipated from history, happily bereft of ancestry, untouched and undefiled by the usual inheritances of family and race. »6 It is not a coincidence that the Terminator arrives from the future naked yet unashamed, indeed incapable of shame: he is Adam’s demonic opposite, a post-postlapsarian nightmare.

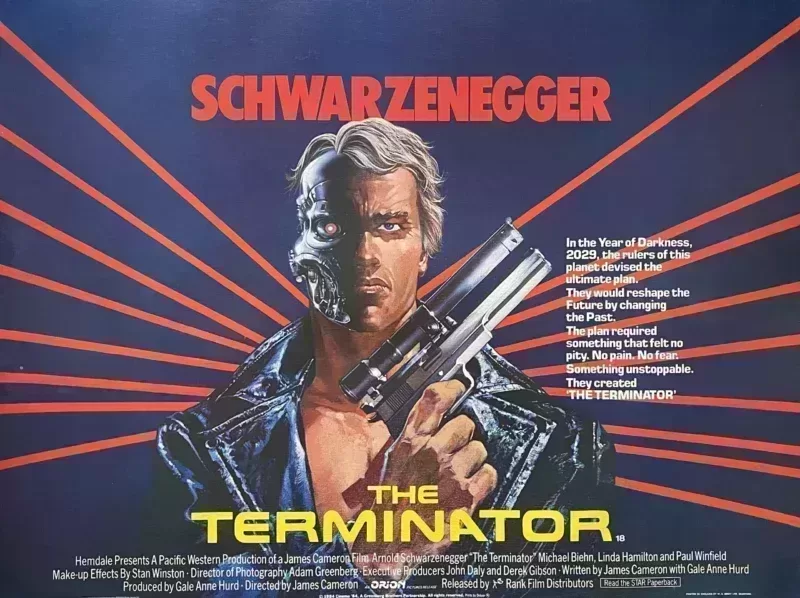

Terminator (1984) was his first foray into science fiction, and he would go on to star in action movies that aspired to profundity: movies about labor and capital, about colonization and decolonization (of Mars), about time and fate, about the action-film economy itself. (Last Action Hero [1993] was Schwarzenegger’s Barbie.) There were also grandly stupid grotesques. True Lies (1994) has it all, and all of it is too clever by half: an interchangeably Arabic terrorist organization called « Crimson Jihad », a surveillance state mobilized to spy on a bored sexy housewife, action as the cure to suburban malaise at the end of history. « You’re fired », Arnold’s Harry Tasker finally says, from the cockpit of the Harrier jet (very expensive), as he launches the missile from which the bad guy dangles, aiming it through a skyscraper at an enemy helicopter.

What really mattered about True Lies, though, is that it was the first film with a production budget larger than $100 million. To fathom Schwarzenegger’s turn to politics, one must comprehend the globalized culture industry at the center of which he now stood.

Total Recall (1990) is pivotal in this history — a garish gem in Schwarzenegger’s action corpus. Schwarzenegger, according to the Hollywood lore, singlehandedly saved the project from so-called development hell and pushed Paul Verhoeven to direct. It was an inspired choice, resulting in a trashily high-concept rumination on false memories and finite planetary resources. Arnold plays Douglas Quaid, an implausibly-jacked construction worker in the year 2084. Bored and listless on Earth, he goes to an entertainment company called « Rekall », which specializes in implanting thrilling memories as if they were real. Entertainment-consumer Quaid picks secret agent on colonial Mars as the fantasy to be implanted, only to realize that the fantasy is in fact his real job (or is it?), setting off the movie’s thrilling chase to Mars.

The movie was filmed in Mexico City, where costs were cheap, and where brutalist skyscrapers could conjure « Earth’s interplanetary imperialism », in the cultural studies scholar Simon During’s compelling reading of the film. Technically an « independent » production (insofar as the studio, Carolco Pictures, Inc., was not one the majors), Total Recall demanded a dizzying array of international capital, and its distribution required « cross-collateralization, in which market performance … in one territory can be discounted against its performance in another. » The movie, meanwhile, itself cannily thematized postmodern means of production and consumption — whether the commodity being produced and consumed was « turbinium » (the fictional mineral extracted from Mars) or an action movie itself. As During distills the movie’s question, « What is more real (more deadly): leisure’s fictions or work’s reality? »7

Given the daunting academic critical exegeses that this (admittedly excellent) movie would inspire, it is refreshing to read Arnold’s own gloriously one-dimensional commentary on it.

The story twists and turns. You never know until the very end: did I take this trip? Was I really the hero? Or was it all inside my head, and I’m just a blue-collar jackhammer operator who may be schizophrenic? Even at the end, you aren’t necessarily sure. For me, it connected with the sense I had sometimes that my life was too good to be true.

His autobiography, I should have mentioned, is called Total Recall: My Unbelievably True Life Story.8 Of the scene where Martian thugs are tricked into shooting at an Arnold hologram, he writes:

In science fiction you can get away with such stuff, and no one even questions it. That’s great, great storytelling; the kind that has international appeal and staying power.

Hard to disagree! Total Recall was among the first movies of this sort to make more money internationally than domestically (and this is not to mention the pirated market). Schwarzenegger, to state the obvious, was on the vanguard of Hollywood’s global market — « he belongs to the global populace », as During put it, writing in 1997. All of which illuminates an economic logic of Arnold’s performances, and of action movies in general. « In his films, his body is a resource available when everything else — guns, money, status, power — runs out », and the genre itself was singularly adapted to the market’s now-global imperatives.

Ever keen to the logics of commodification, Schwarzenegger could understand himself as a mass of muscled capital, the function of which was to generate more capital. It’s no wonder so many of his movies have him encounter another version of himself, always goofily. Last Action Hero (1992) is a meta-cinematic exercise in which the fictional action hero « Jack Slater », played by an in-movie « Arnold Schwarzenegger », escapes the fictional world for the real one. The in-movie Arnold will marvel at « the best celebrity lookalike I’ve ever seen », while the fictional character will tell him, « Look, I don’t really like you; you’ve brought me nothing but pain. » In The 6th Day (2000), Arnold teams up with his own clone to bring down the evil cloning company — a nod, I’d argue, to the pirated copies of Schwarzenegger movies around the globe, and the millions of dollars that Hollywood thereby « lost ».

a mass of muscled capital, the function of which was to generate more capital.

What does such proliferating success do to a person’s political and economic imagination? In 1997, Schwarzenegger, after learning he’d been born with a bicuspid aortic valve, had the first of several open-heart surgeries. A moment of humanizing vulnerability? — sure, yet therefore also an event that had to be properly messaged, given the financial stakes for the action-hero industry in which he played so large a part. It is both surprising and not surprising to learn that he brought successful libel cases against a German doctor and a tabloid that predicted his early death.

Or consider another example from the ledgers of action-movie futures: Imagine you’ve finished shooting a movie called Collateral Damage, with a production budget of $85 million, in which you play a firefighter whose family is killed when a building is bombed, and who thereupon goes to Colombia for vengeance and/or justice (it was Libya in earlier versions of the script), and in the process heroically foils a terrorist plot to bomb the US State Department. Now imagine that this movie was set to appear in theaters on 10 October 2001, and had to be delayed by the September 11 attacks.

This, if you were Schwarzenegger, might feel like the stuff of high finance and global geopolitics, indeed an education for politics, for the burdens of statesmanship as a Weberian calling. For such a celebrity-businessman or businessman-celebrity, becoming governor of what is routinely and annoyingly called « the fifth largest economy in the world » (sixth-largest when Arnold took over) was less a departure than a continuation, or maybe even a lateral move.

And so it was that in 2003, in his mid-fifties, Schwarzenegger put movies (mostly) aside to become the Republican governor of California, in a zany recall election — or, more precisely, a zany and chaotic coup.9 Notwithstanding the performative stupefaction that greeted his victory — what? Schwarzenegger?! — his move to politics was entirely logical, entirely in keeping with the Reaganite trajectory he had so enthusiastically embraced. Scratch that: it was importantly different from the Reaganite trajectory, because Ronald Reagan, when he turned to politics, was a B-lister at best. Reagan « used to be in Westerns », but Schwarzenegger didn’t « used to » do anything: he announced his bid for governor only a month after the release of Terminator 3: Rise of the Machines, in an appearance on the Tonight Show in August 2003.

The « Governator » spawned a cottage industry of commentary on the politics of the spectacle, and it may be tempting, now, to see Schwarzenegger as the vanguard of celebrity pseudo-populism, the more demonic expression of which would eventually arrive in the figure of Donald Trump. But that would be drawing the line too straight. Better, for the moment, to note that in 2004, a month after Barack Obama wowed the Democratic National Convention channeling « the hope of a skinny kid with a funny name who believes that America has a place for him, too », Schwarzenegger, who has a funnier name, assumed the analogous podium at the Republican National Convention to channel a similar skinny-kid aspiration. « To think that a once-scrawny boy from Austria could grow up to become Governor of the State of California and then stand here — and stand here in Madison Square Garden and speak on behalf of the President of the United States. That is an immigrant’s dream! It’s the American dream. »

Once he’d become the union-antagonizing governor, the real moral of the Terminator story could become miserably simple. The premise of Terminator is that in the future, a corporate computer program becomes self-aware, declares nuclear war on humanity itself, and then sends an unstoppable cyborg (Arnold) back in time to murder the mother of the leader of the human resistance before that leader has even been conceived. It’s a powerfully simple action premise that will become stupidly convoluted in later installments (about which more below). But look past the time travel, the sunglasses, the explosions: what was this emotionless robot from the future, really, if not a « quintessential neoliberal Frankenstein, » as one analysis put it, « the labor-killing machine »?10 And what was the Terminator’s melodrama — malevolently self-aware computers declaring nuclear war on humanity-in-general — but an obscuring of the class warfare waged in dismal reality? The lurid apocalyptics of the day the machines would initiate their attack, « Judgment Day », would then echo, in this account, the manufacturedness of the perpetual budgetary crisis used to justify unemployment and austerity.

That account doesn’t capture the convolutions of his actual tenure as governor. Having ascended to the position by referendum, Schwarzenegger called for a special referendum in 2005, with ballot measures introducing austerity and targeting teachers’ and public sector unions. They all failed. In the wake of that costly failure, he restyled himself as an aisle-crossing moderate and as the rare climate-friendly Republican. He was re-elected in 2006, but his popularity plummeted in the wake of the 2008 crash — California’s meltdown was among the most severe — the repercussions of which he tended to blame on the legislature and on unions. What is now held aloft as his signature success is the Global Warming Solutions Act of 2006 — a cap-and-trade policy to reduce carbon emissions, a notable achievement of subnational climate policy-making. That policy was articulated against a national government that was doing nothing; it now stands as a measly American something.

Spectacle aside, the Governator moved cannily within the neoliberal order’s spectrum: a celebrity populist whom a New Yorker profile would call a « Supermoderate! » in 2004. In retrospect, his report card would score solidly in what had become the American political center, or even on the progressive side (a low bar): awkward disillusionment with the Iraq War, openness to market-based climate regulation, capitulation to draconian nativism (denying drivers licenses to undocumented immigrants was one of the immigrant governor’s sops to the right), all of it remarkably unremarkable.

The end of his governorship in January 2011 coincided with a fall from grace: the revelation in May of a « love child », fourteen years old, who’d aged into undeniable Schwarzeneggerian resemblance.11 Arnold had married into the Kennedy dynasty in 1986 (Maria Shriver is JFK’s niece); their divorce doubly resonated as celebrity news and political news. This familial crumbling was not the only hurdle, alas, on his destined course. The obvious next rung of his ambition was the American presidency, but it was closed to him by the absurd constitutional requirement that the president be a « natural-born citizen ». An amendment to the constitution proposed by Utah Senator Orrin Hatch in 2003 — the « Arnold amendment » — never even made it out of committee.

There follows a period of drift. Schwarzenegger’s biography fits, with some tweaking, to the schema laid out by Carl Jung in « The Stages of Life » (1930). Jung proposed four stages, the second of which tracked the upward climb of adulthood and the inevitable arrival at a plateau. From below, so to speak — or during the climb — the plateau isn’t visible; we can’t fully see the realizations we’re climbing toward. In Jung’s schema, a man’s plateau comes at around forty; for Schwarzenegger, I’m extending that deadline about two decades, partly to accommodate the nonstandard, nonsensical trajectories of absurdly wealthy and famous male celebrities, but more because Schwarzenegger’s post-governatorial flailings constitute a mid-life crisis in the most robust Jungian sense.

Jung lamented the human tendency to enter life’s third stage as if we were supposed to continue fighting and winning the second stage’s battles. To carry on in that stage « with the false assumption that our truths and ideals will serve us as hitherto » was the near-universal error, an error that would only bring some measure of melancholy or despair. After all, « we cannot live the afternoon of life according to the programme of life’s morning », Jung wrote, « for what was great in the morning will be little at evening, and what in the morning was true will have become a lie. » Arnold (2023), the documentary, for all its militant cheerfulness, cannot help but betray a melancholy sense of its own non-reason-for-being. It has the feel of a campaign video for a job one is ineligible for. Funereal despite itself, it presents a poignant figure, at once reconciled to the latter stages of life, and yet at the same time annoyed at death’s existence, and able to express that annoyance only in the simplest and most childish way.

One detail in the first episode stuck out to me: recounting his childhood, Schwarzenegger recalls fantasizing that his real father was an American GI in occupied Austria, that he had a secret patrimony different from his broken Nazi father. It is a revealing if only. Such a family romance would, of course, make him eligible for the presidency: the Austrian claimant. We might think of it, too, as the kindly liberal Republican counterpart to the sinister delusion that Obama was really born in Kenya. It is also an eerily comic anticipation of the illegitimate Arnold-offspring’s probable fantasy that his real father was Arnold Schwarzenegger — a fantasy that was realized, unlike Arnold’s own.

a mid-life crisis in the most robust Jungian sense

One cannot help but imagine the alternate history. The Secret Service agents tasked to protect President Schwarzenegger would be punier than the man they were protecting, an incongruity that the First Immigrant President would joke about often. He’d make occasional winking cameos in movies, which might or might not violate the Federal Communications Commission’s « equal-time rule » (opponents being denied comparable cameos). These questions would fade, and the humor and the novelty would wear off soon enough. The neoliberal order, with some new progressive trappings, would hold. Soon after his reelection, the Commando-in-Chief would opt to be motorcaded around not in a bulletproof presidential limousine but in a presidential Hummer (It was Schwarzenegger — in actual history, not just the alternate history — who first pushed a civilian version of the military’s Humvee to market in the early 90s), albeit a Hummer that had been converted to electric: Eco-Hummer One.

With that destiny foreclosed, Schwarzenegger returned to Hollywood, firing a bunch of machine guns in 2012’s Expendables 2, the franchise in which the boomer hardbodies who’ve aged into self-parody capitalize on the parody. But returning to Hollywood only deepened the predicament, because Hollywood itself had changed. The old quips didn’t land in the same way. And — more uncannily still — all the other male movie stars had become weirdly jacked. Child actors were graduating into a pointless and implausible shreddedness. Schwarzenegger returned to the reliable Terminator franchise. In Terminator Genisys (2015) — his fourth time playing the role — he is « Pops », another one of the good terminators sent back in time to protect the young Sarah Connor so that her son can grow up to resist the machines. The film opens with a poignant drama of obsolescence, in which 67-year-old Schwarzenegger battles a 37-year-old version of himself, digitally reconstructed from the first Terminator.

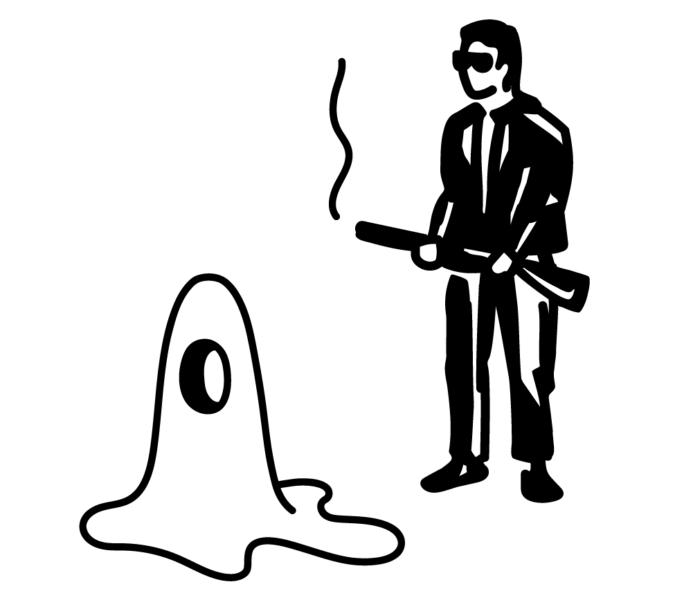

In fact, obsolescence had already become the Terminator franchise’s abiding theme. Just as Frankenstein’s monster becomes more human than his creator, so the Terminator sequels anticipated this existential drift more penetratingly than Arnold himself could. The first Terminator was simple and stark; Terminator 2 (1991) cast Arnold as a protector-Terminator, and thenceforward the films should be understood less as action-movies-of-ideas than as meta-exercises in Schwarzeneggerology themselves — that is, as existential Schwarzeneggerological comedies. An Arnold will always come back, and then always die. It will arrive naked in the world, its first task being to clothe itself. In Terminator 2 the Arnold gets its leather from a biker bar. In Terminator 3, the Arnold approaches what we expect to be another biker bar, but surprise! — it’s ladies’ night at a strip club, and the Terminator is welcomed with squeals of pleasure.

Each Terminator movie has to up the technological ante of the evil Terminators to be vanquished so that humanity can endure: merciless upgrades, with model numbers, each one a sinister allegory of special-effects innovation itself. There’s the molten metal man of Terminator 2 — the T-1000 — and the female Terminator of Terminator 3 — the T-X. Each Terminator movie must then, correspondingly, escalate the jokes about the Arnold-Terminator’s own inevitable obsolescence. Each Arnold — the lowly T-800, model 101 — is spit from an assembly line of the future and sent back in time, but even in the past it won’t be new: it’s a no-longer-supported app, installed on an aging chassis. It arrives, if the term will be forgiven, always already obsolete, immer schon überholt. Hence the deadpan gallows’ humor: « Your levity is good, » says the rusty robot from the future who cannot understand what you humans call a joke: « it relieves tension and the fear of death. »

always already obsolete, immer schon überholt

The well of obsoleteness-humor inevitably runs dry, but Terminator 3 delivers one good joke, at least. The Arnold battles the superior « Terminatrix » in a men’s room. A urinal is smashed over her head, with zero effect. It is action cinema’s slapstick nod to Duchamp’s Fountain. There’s a comic pause, ever-so-slight, to let the Arnold look at the broken urinal, one readymade beholding another.

Celebrity politics in its more toxic form would pass him by as well. After Trump’s election in 2016, Schwarzenegger took over the helm of Celebrity Apprentice, determining the fates of Boy George, Jon Lovitz and Snooki, among others. It was a low point. Trump’s odious « You’re fired » became Schwarzenegger’s sad « You’re terminated », sad because dickish boardroom CEO wasn’t a natural Schwarzenegger persona: he’d been in Kindergarten Cop! The show was cancelled after one season.

All of which explains, if that’s the right word, both the familiarity and the strangeness of the Schwarzenegger who reemerged in the Trump and Covid years: the weird former action star, now also a YouTube and Instagram personage, issuing reflections and motivations from his sprawling yet folksy mansion, a simulacrum of ruralism complete with a donkey (Lulu) and a miniature horse (Whiskey). Schwarzenegger became an un‑Trump, and the Schwarzenegger homestead became the un-Mar-a-lago: close to the land, gemütlich, a Tolstoyan idyll interestingly reminiscent of the mitteleuropäische landscape that he’d left behind. For Jung, it was a pity that modern civilization, particularly American civilization, had become blind to the cultural and spiritual possibilities of that third stage of life, after we had entered our afternoon but before our evening senescence. Schwarzenegger, though, seemed to find at least some inkling of those possibilities, and even a capacity for historical self-reflection.

The mantle of avuncular elder statesmanship presented itself after the storming of the Capitol on 6 January 2021. Schwarzenegger achieved virality with an earnest video oration that likened the stormers to the Stürmers of Kristallnacht. Sitting in a mahogany office, a shirtless photo from his bodybuilder days visible on the wall behind him, he spoke of his childhood in postwar Austria, of his abusive Nazi father, of the broken men who’d embraced a « loser ideology ». In that speech’s climax, he wielded once again the sword from Conan the Barbarian, this time as a symbol of democracy’s resilience. « This is the Conan sword », he says, assuming we know what that is, which we do.

Here’s the thing about swords: the more you temper a sword, the stronger it becomes. The more you pound it with a hammer and then heat it in the fire, and then thrust it into the cold water, and then pound it again, and then plunge it into the fire and into the water, and the more often you do that, the stronger it becomes. I’m not telling you all this because I want you to become an expert sword maker, but our democracy is like the steel of this sword. The more it is tempered, the stronger it becomes.

Stirring! It was a message about swords and democracy that I am sure some people needed to hear. It was also a rhetorical tableau that would be very difficult to explain to a historian of the future. I have my doubts about whether artisanal steel-production is a good metaphor for democracy, but I can only marvel at a genre transformed: one era’s sword-and-sandal gore — at once absorbingly campy and inchoately reactionary — is tempered into another era’s earnest liberalism.

« This is the Conan sword », he says, assuming we know what that is, which we do.

Schwarzenegger lives in a private museum of these totems. He poaches from that museum to speak with gravity to a present that might benefit from his now historic-seeming experience. Upon the Russian invasion of Ukraine, he addressed the Russian people as a « longtime friend », with a message about the evils of propaganda. It feels old-fashioned, like a digital version of the paper leaflets dropped over enemy lines in an earlier era’s wars. His own Nazi father, he says, was « all pumped up on the lies of his government » when he arrived in Leningrad to face the Red Army, only to come back « broken, physically and mentally. » He speaks of his childhood idolization of the Russian bodybuilder Yuri Vlasov, « the first human being to lift 200 kilograms over his head » (while wearing glasses, endearingly). He turns for Schwarzeneggerological inspiration not to Conan but to Red Heat (1988), a buddy movie with Jim Belushi, in which Arnold plays a comically humorless Soviet police officer, and which was the rare Hollywood movie to film a scene in Red Square.

Another video documented his visit, in the autumn of 2022, to Auschwitz, and delivered a message against anti-Semitism, hate and paranoia. (« Let me tell you something. The weight on your back hits you at the very beginning, heavier than any squat I’ve ever done. And it never goes away. ») He wrote « I’ll be back » in the Auschwitz guestbook, which elicited some snark, but I take the expression to be genuine and unironic, a commitment to return. He does want to come back.

For three decades, Schwarzenegger played — for the culture and for himself, cartoonishly or earnestly — the role of Übermensch on screen, in various permutations, and the culture-at-large took that role seriously, or satirized it. (It was taken seriously enough to satirize.) I mean Übermensch in every sense of that loaded term, from the kitschy to the philosophical, from the fascist eugenic fantasy (a perversion of the Nietzschean term) to the Übermensch that Nietzsche actually conjured. Schwarzenegger ran the gamut of them. Nietzsche’s Übermensch emerged out of a philosophical interrogation of history and history-writing: what distinguishes the Übermensch is a peculiar freedom from history, or, more precisely, a freedom from the stasis and melancholy wrought by the modern historical imagination itself. Nietzsche critiqued the historical consciousness of his own era as an enervating orientation to the world, and sought instead « a concept of history that engenders action, not reflection », in Elizabeth Grosz’s powerful distillation.12 The Übermensch can forget, and therefore invent.

The best

Schwarzenegger-led

movie, if you are

wondering, is Twins,

from 1988.

Take out da papers and da trash

…The best Schwarzenegger-led movie, if you are wondering, is Twins, from 1988. The director who discovered and most fully harnessed the comic potential of Arnold-as-Übermensch was Ivan Reitman, Czechoslovak-born son of Hungarian Jews, in a film that deserves an essay of its own…

A parody of eugenics, Twins casts Apollonian Arnold and Dionysian Danny DeVito as the separated offspring of a mid-twentieth-century experiment « designed to produce a physically, mentally and spiritually superior human being. » Twins’ joke, which is also the moral of the story, is that the real figure of self-reliance and self-invention isn’t Arnold’s genetic superman but Danny DeVito’s « genetic garbage ». The movie’s first five minutes are a masterclass in economical storytelling, culminating with yet another Arnoldian entrance into modernity: on the plane to LA, wearing headphones, jubilantly singing along to « Yakety-Yak » in an exaggerated version of his own accent:

Take out da papers and da trash

Or you don’t get no spending cash

If you don’t scrahp zhat kitchen flo-ah

You ahyn’t gonna rock-n-roll no mo-ah

« Excuse me », Arnold replies to the stewardess’s flirtatious scolding, « I just have never heard this kind of music before. » For a movie riffing on « genetic garbage », the song is well chosen — and was written for The Coasters, moreover, by the Jewish songwriting duo of Leiber and Stoller.

Schwarzenegger’s various roles are riffs on that figuration, and they’re varyingly smart or stupid, conscious or unconscious, cheap or earned. (The best Schwarzenegger-led movie, if you are wondering, is Twins, from 1988. The director who discovered and most fully harnessed the comic potential of Arnold-as-Übermensch was Ivan Reitman, Czechoslovak-born son of Hungarian Jews, in a film that deserves an essay of its own.) The figuration inflects his politics, too. He arrived in America as a total ideological naïf; he entered American history uniquely free from American history, ready for his conversion to the religion of the market. Schwarzenegger ditched « socialism » not because he understood socialism or found it unjust, exactly, but because it seemed, well, old and boring and stuffy, a constraint on the individualist destiny he knew to be his.

And from that pedestal of ersatz Übermensch, he stepped into the more mundane arena of politics, from the undemocratic market of global celebrity into the ostensibly democratic, or ostensibly liberal, world of government. (As governor, he delighted in the company of neoliberalism’s favorite economist, Milton Friedman, who happened to be Danny DeVito’s size: « It’s Twins 2! » he said.) Schwarzeneggerian politics was a buddy comedy pretending to be an action movie.

And now? The Arnold of our own era radiates a we-can-do-it positivity, a relentless optimism, emphasizing, for instance, the solvability of climate change, if only we’d all get together and will it. He is likely to be perplexed by others’ lack of drive or discipline, confused by other people’s griefs — surprised, in fact, by his own griefs. One refrain of the Netflix documentary is Arnold musing about his own differentness — I’m just built differently — but with an edge of sorrowful perplexity about his own Übermenschlichkeit. Why would I have been born incapable of pessimism?

There’s nothing more boring than success. Schwarzeneggerology becomes, I would submit, most interesting at this juncture: no longer merely an interrogation of the success myth he’s hammered so relentlessly, but an inquiry into failure of an almost metaphysical kind. The last Terminator movie (one hopes) brings unlikely consolation, as the cyborg-assassin from the future is tasked, finally, with expressing a chastened consciousness in a fallen world. In Terminator: Dark Fate (2019), the Arnold-Terminator has succeeded in killing the future-resistance-leader whom it was sent back in time to kill. It then grows old, and when when we encounter it, it has been living (not unlike the real Schwarzenegger) in a spacious cabin in the woods. This Terminator gets to tell its story, for it has adapted to a world that prizes therapeutic vocabularies. « When my mission was completed, » it says, « there were no further orders » (the malevolent future-AI never thought to write a code for what to do next), and so, « for twenty years, I kept learning how to become more human. » It meets a woman! Or rather rescues her, along with her child, from an abusive husband: « She had nowhere to go », it says. « Caring for this family gave me purpose. Because without purpose, we are nothing. » Pinocchio became a real boy; the Terminator becomes an aging pater familias. They should have called it Terminator Finds a Son!

His scandals consigned to the past, Schwarzenegger has graduated into the pantheon of self-help with Be Useful: Seven Tools for Life, published in October 2023.13 To happen upon him today is to encounter an Übermensch emeritus, swimming against the tide of « toxic masculinity » to salvage a useful masculinity for an age that has no use for the hyper-masculinity he typified. Ironies abound in this denouement, poignant or absurd. A good action movie isn’t useful, after all, but gloriously useless. A bodybuilder’s muscles aren’t pumped for the using but for the glistening. Usefulness, for Schwarzeneggerology, is not a goal but a side effect. Bildung isn’t the point of Pop Art, any more than grain is the point of the Wheel of Pain.

- The « Wheel of Pain » is now one of the strongman competition events at the « Arnold Strongman Classic ». ↩︎

- The US title was Hercules and the Captive Women. ↩︎

- Richard Dyer, « The White Man’s Muscles », in White (Routledge, 1997). ↩︎

- Susan Jeffords, Hard Bodies: Hollywood Masculinity in the Reagan Era (Rutgers University Press, 1994). ↩︎

- He was also, along with Willis and Stallone, the main face of, and investor in, the Planet Hollywood chain of restaurants, which rose and fell in this same era. ↩︎

- R.W.B. Lewis, The American Adam: Innocence, Tragedy and Tradition in the Nineteenth Century (University of Chicago Press, 1955). ↩︎

- Simon During, « Popular Culture on a Global Scale: A Challenge for Cultural Studies? » Critical Inquiry 23, no. 4 (1997): 808–33. ↩︎

- It was co-written with Peter Petre, whose co-writing resumé also includes the memoir of Alan Greenspan, the Reagan-appointed chair of the Federal Reserve. ↩︎

- Long story short: the effort to oust Governor Gray Davis was spearheaded and funded by anti-tax crusaders taking advantage of California’s openness to ballot initiatives and referenda. That openness is a once « progressive » measure, but since the 1970s, it has more often been co-opted by the right. Davis was a centrist Democrat who had borne the brunt of the millennial electricity crisis as well as the bursting of the « dot com » bubble. The recall’s flame was further fueled by the scapegoating of immigrants. Schwarzenegger, looking back on the speed of the campaign in the Netflix documentary, observed: « It’s like in Europe. Two Months. Bang. » ↩︎

- Jeffrey Broxmeyer, « From the Silver Screen to the Recall Ballot: Schwarzenegger as Terminator and Politician », New Political Science 32, no. 1 (March 2010): 1–21. ↩︎

- « Love-child » has an old German pedigree, reaching back to Das Kind der Liebe (1790), a play by August von Kotzebue. ↩︎

- Elizabeth Grosz, The Nick of Time: Politics, Evolution, and the Untimely (Duke University Press, 2004). ↩︎

- « The useful is what is at hand, available for use now », Elizabeth Grosz observes in her reading of Nietzsche. « Nietzsche himself, though, is concerned with a different — deranged — sense of usefulness, the useful in nondeterminable contexts, the useful for a future that cannot be predicted, in other words, a useful that is not so much of use but awaiting the invention of a use from its current excess. » The Nick of Time ↩︎