Earth for All: A Survival Guide for Humanity

Sandrine Dixson-Declève, Owen Gaffney, Jayati Ghosh, Jørgen Randers, Johan Rockström, and Per Espen Stoknes

New Society Publishers 2022

Half-Earth Socialism: A Plan to Save the Future from Extinction, Climate Change, and Pandemics

Troy Vettese and Drew Pendergrass

Verso 2022

Limits to Growth: A Report on the Predicament of Mankind

Donella H. Meadows, Dennis L. Meadows, Jørgen Randers, and William W. Behrens III

Potomac 1972

« We are fucked » vs. « It’s not too late ». The Club of Rome’s Earth for All offers a burst of stubborn optimism. But when does stubborn optimism become cruel optimism?

Victor Frankl once compared optimism to laughter: If you want people to laugh, really laugh, then you must provide them with a reason for it. You must tell a joke, or do something funny. It is impossible to evoke real laughter just by urging someone to laugh. « Doing so would be like urging people in front of a camera to say ‘cheese’, » Frankl explained, « only to find that in the finished photographs their faces are frozen in artificial smiles. »

The phrase « it’s not too late », for me, brings an artificial smile. I stumble onto it as I walk into a bookstore and see the flashy Carbon Almanac (2022) promoted at the entrance, one of many such books to appear in the last, late year. It shouts from the cover: « It’s not too late. » The foreword was written by Seth Godin, a marketing guru out of the dot-com avantgarde. What will save us is « the hope that comes from realizing that it’s not too late. » The refrain is a staple of the genre. Another entry, a new report from the Club of Rome entitled Earth for All: A Survival Guide for Humanity, offers a kindred burst of optimism about the future against the backdrop of a bleak present. Greater planetary health and social well-being are within reach. The authors will « show you that this is indeed fully possible ». Meanwhile the heavy-weight United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), released two punchy reports of its own in 2022. They hammered the message that countries’ pledges to cut emissions fall far below climate change targets, and that the impact of climate change is already devastating for many parts of humanity, the ecosystem, and for the biodiversity that now suffers a mass extinction.

Earth for All may have drowned in the sea of climate commentary. But it is worth reading, for what it is, and what it is not.

We must begin, though, in an earlier era. The Club of Rome was founded in 1968, when the Italian business manager Aurelio Peccei, formerly of Fiat and Olivetti, convened thirty intellectuals, entrepreneurs and civil servants from ten countries to study, with urgent concern, the « predicament of mankind »: poverty in the midst of plenty, degradation of the environment, insecurity of employment, as well as inflation and other monetary and economic disruptions.

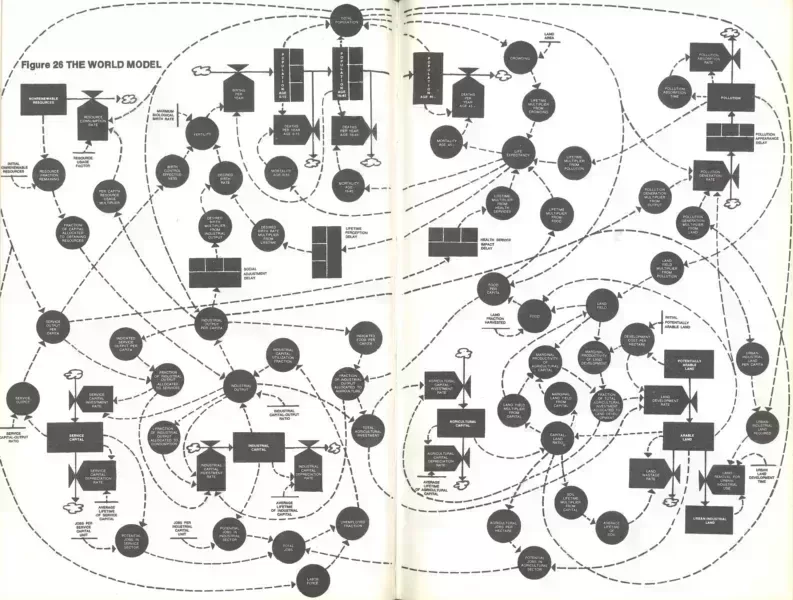

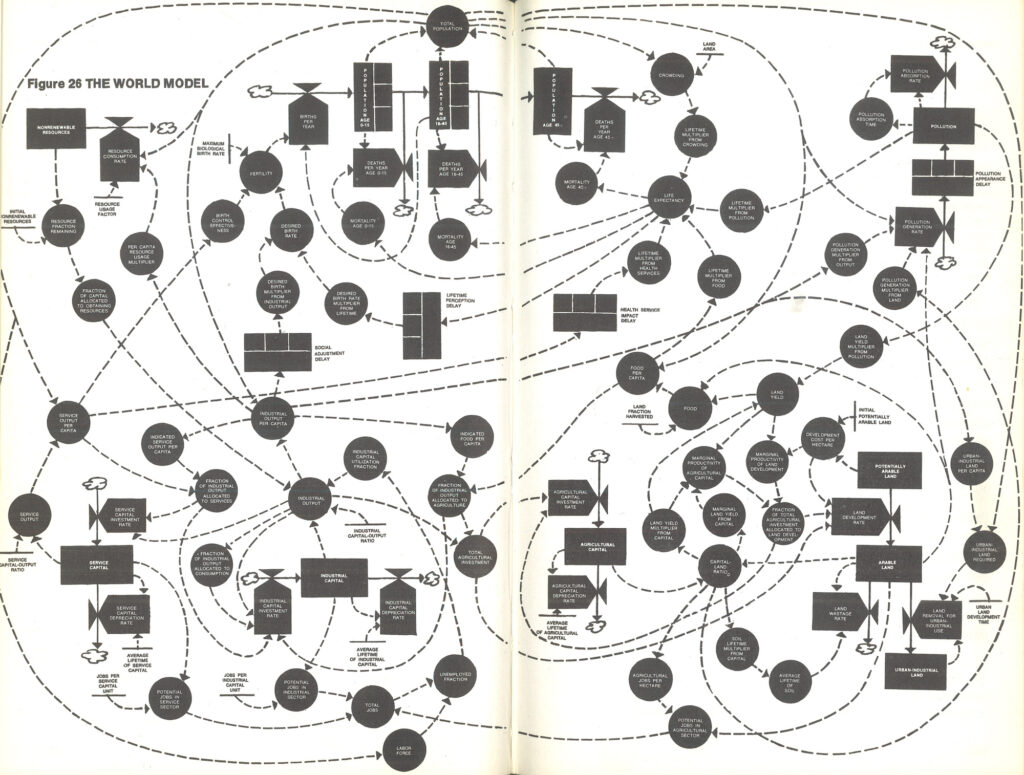

What were the dynamics driving this predicament, and what was the future likely to be? The capacity to answer these questions through complex and dynamic models increased rapidly at the time of the Club’s creation. Listening in at the Club’s first meeting in 1968 was Jay Forrester, a professor at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) and a pioneer of computer engineering, cybernetics and the study of systems dynamics: Conversant in the study of circular causality, or feedback loops, Forrester had developed a prototype of a formal, written model of nothing less than the world, which he would spell out in his book World Dynamics (1971). Dennis Meadows, then a 30-year-old professor at MIT, took over from Forrester the work of modeling possible futures. Those models are at the core of the Club of Rome’s iconic first report, Limits to Growth, which appeared in 1972. With large amounts of data and then-new computing technology, Meadows and his team modeled the five closely intertwined variables that Peccei had deemed key: population, food production, industrialization, pollution, and resource use.

A group of six young researchers fed data on those five variables into their monstrous « World 3 model » and summarized the model’s behaviour to draw out developments such as population growth and resource use in relation to what they calculated as the carrying capacity of the planet. Like any model, World 3 was an abstraction from reality, boiled down to an ordered set of assumptions about complex systems — « imperfect, oversimplified, and unfinished », as the researchers acknowledged in the report. But compared to what had been done before, it appeared much better, closer to the messy reality of myriad interconnections. It also claimed to reach further into the future: up to one hundred years.

THE WORLD MODEL

from Limits to

Growth

THE WORLD MODEL from Limits to Growth

A data-lover’s centerfold, the model spreads over a double page with a whirl of dashed lines and arrows to indicate relationships of causation.1 The report distilled twelve snapshot scenarios of possible futures from the model’s spittings, according to various assumptions about resource use, agricultural productivity, controls placed on pollution, capital, and — most controversially — birth rates. Innocent looking graphs sketched scenarios of salvation or doom: A dip in the population curve could mean the death of one or more billion people.

Limits to Growth made a splash with its finding that there are definite limits to growth on a finite planet, and that we would encounter those limits in the next generation (ours). If we ignore the limits, the authors averred, civilization will collapse: « A decision to do nothing is a decision to increase the risk of collapse. » A concern for human flourishing must therefore replace a fixation on economic growth.

The report became a bestseller. The specter of catastrophic collapse caught the attention of the media and the public. It chimed, in 1972, with the turmoil of food and oil crises, with growing environmental awareness and with global thinking. That year, the first world conference on the environment was held in Stockholm, and the Apollo 17 crew took their famous photograph of the Earth — The Blue Marble — on their way to the moon.

Environmental and systems scientist Donella Meadows was the gifted lead author of Limits to Growth. She and Dennis were a young couple at the time. She conveyed urgency with a now perhaps well-known parable:

Suppose you own a pond on which a water lily is growing. The lily plant doubles in size each day. If the lily were allowed to grow unchecked, it would completely cover the pond in 30 days, choking off the other forms of life in the water. For a long time the lily plant seems small, and so you decide not to worry about cutting it back until it covers half the pond. On what day will that be? On the twenty-ninth day, of course. You have one day to save your pond.

The lily pond impresses on the reader an uneasy sense of the suddenness with which exponential growth bumps against fixed limits. It sustains the report’s anxiety, in 1972, that humankind had not learned, and wouldn’t.

Limits to Growth’s brighter scenarios of a stabilized world are largely forgotten. Such a world could be made possible with stabilizing policy interventions such as a birth rate equal to the death rate, and a rate of capital investment equal to the rate of depreciation. If introduced by 1975, those policies would have enabled « the equilibrium state » in which human needs could be met and the carrying capacity of the planet would be respected. The vision was of a world not addicted to growth, but with people reveling in their new-found freedom and reconnecting to the multiple meanings of life.

Futures could now be known, and therefore be changed. The report was alarming but also optimistic. Problems were daunting, but « easily solvable if human society decided to act ». The final scenario set a deadline, warning that the equilibrium state could no longer be reached if the stabilizing policies were not introduced before 2000. The authors of Limits to Growth knew that a socio-economic transformation would evoke resistance and would not come about without struggle. The equilibrium state « would make fewer demands on our environmental resources, but much greater demands on our moral resources ». It would no longer be possible to avoid questions of distribution, of « explosive gaps and inequalities ». But politics was not really their theoretical terrain. Politics remained a placeholder waiting to be filled in.

The report nevertheless made limits a political keyword — one that politicians from across the ideological spectrum would defy. Ronald Reagan quipped soon after the report’s publication that « there are no great limits to growth because there are no limits of human intelligence, imagination, and wonder. » At the Earth Summit in Rio in 1992, George H.W. Bush opined that « twenty years ago some spoke of the limits to growth, and today we realize that growth is the engine of change and a friend of the environment. » Limits to Growthwas astutely critical of a complacent faith in technology — « Applying technology to the natural pressures that the environment exerts against any growth process has been so successful in the past that a whole culture has evolved around the principle of fighting against limits rather than learning to live with them. » Still, in 2022, at a side-event to Germany’s G7 Presidency, Chancellor Olaf Scholz was asked what is needed more than anything else in the climate catastrophe. He answered without hesitation: « Trust in technological progress. » Period.

In hindsight, Limits to Growth looks prescient, even prophetic. Overall, its scenarios map rather well onto what has happened in the meantime. I met Dennis Meadows in the summer of 2022 when he spent a couple weeks in Hamburg at The New Institute where I have been a fellow. When he now looks back at Limits to Growth, he still sees a degree of naiveté in its hope that new knowledge would lead to transformative action. He now predicts the collapse of civilization, simply because of natural processes that are already under way, out of control no matter what we do.

The Club of Rome’s latest report, Earth for All, was timed to coincide with the fiftieth anniversary of Limits to Growth in 2022. Dennis Meadows took no part in it. (Donella Meadows died in 2001.) The Club has continued, as its website informs, as an « organisation of individuals who share a common concern for the future of humanity and strive to make a difference. » There are now a hundred members, and the Club has produced over fifty reports, none of which has garnered the attention of the first. A profusion of new actors now compete with the Club for the spotlight. Earth for All wants to regain the fame of Limits to Growth, but it keeps that iconic report at arm’s length.

Where Limits to Growth laid out twelve scenarios, Earth for All offers two: « Too Little Too Late » or « Giant Leap ». Our fate hinges on « policies of system change ». The report lists five « turnarounds that should transport us into the next decade »: eliminate poverty, reduce inequality, empower women, transform food systems, and redesign the energy system. These turnarounds will not only avert the climate catastrophe, but also lead to lives that are fitter, happier, and more productive. There’s a new model, too: « Earth 3 », building on the « World 3 » of Limits for Growth. The complex of causal relationships spreads once more across a data centerfold, though now relegated to an appendix. The focus is again on world population, and then on global warming, poverty, inequality, social tension and average well-being. Earth for All has a greater wealth of data to combine with far more potent computing power. Its model runs on ordinary computers within a few seconds. The report even invites you to play « the Earth for All Game » (not yet available, alas), to « game together » and create your own future.

It’s all rather clunky. Without Donella Meadows, the new report’s language is inelegant, sometimes incoherent, with unwieldy sentences and maladroit metaphors for time and space. 2A document of muscular modernity, it reads like a promise of personal perfection — strong legs and a six-pack in six weeks. « Turnarounds », meanwhile, is a curiously backwards word. The key demands are phrased in techy metaphors: a « reboot of civilization’s guiding rules before the system crashes ». « A major upgrade ». « A reset ». Etc.

The authors are professional optimists. Earth for All was written by six main authors, four contributing authors, and several other contributors, many of whom are linked to the Transformational Economics Commission, a group of economic thinkers. One can only imagine the exhausting video-calls, the documents that broke down under the weight of tracked changes. The foreword was written by Christina Figueres, the former Executive Secretary of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCC) who once led climate negotiations from the failures in Copenhagen in 2009 to the Paris Agreement of 2015. Figueres then co-founded Global Optimism, a think tank that proclaims: « Stubborn optimism is a deliberate mindset ».

What are the policies that Earth for All suggests? One trillion US dollars per year from the International Monetary Fund (IMF) for « green jobs-creating investments »; the cancellation of all debt owed by low to high-income countries; a reform of the World Trade Organization (WTO) that « enables leapfrogging » to decrease inequality between countries; a hefty tax increase on the rich to turn domestic inequalities around; strengthened worker rights for the same reason. Some other demands: introduce a citizens fund that pays out what nature is worth in financial terms, boost the world-wide education of girls and women, demand gender parity in public and private leadership, improve pension schemes, eliminate food waste and overconsumption, achieve more efficient farming, transform diets to respect planetary boundaries, phase-out fossil fuels, electrify everything and offer at least one trillion dollars for investment in renewables.

Sensible! Or rather: too sensible! In fact one can see the domestication of radical borrowings at work throughout the report, as in the late chapter on « commoning », the cooperative practice of resource management under conditions of shared usage rather than private ownership. The report’s authors propose to scale up the practice and redistribute benefits from nature in monetary form, thus creating financial incentives and contributing to the political feasibility of certain climate policies. But this turn to monetization and financial incentives fosters precisely those anthropocentric and instrumental postures that the practice of commoning wishes to counter and transform. The report’s wish to be operational — realistic! — softens the punch. Change without changing. A hybrid SUV.

Why, the authors ask, have all these eminently sensible policies not yet been adopted? « If the benefits are so great and the investments so small, relatively, what is holding us back? » The answer steadfastly avoids the question: « Ultimately, our mindset; the all-pervasive winner-takes-all worldview. » Earth for All bests the winner-take-all worldview with win-win scenarios, propounded with relentless faith. There are no losers on its two hundred pages. But it is sadly easy to deflate this mandatory optimism. For example: at least sixty percent of all unextracted oil and fossil methane gas known to exist, and ninety percent of all un-mined coal, a study in Nature has found, are already, economically speaking, above ground, having been sold, licensed, budgeted and leveraged as assets against debt. The destruction of the planet remains hugely profitable and legally protected.

Fifty years ago, the writers of Limits to Growth feared societal collapse because of our incapacity to learn before it is too late. Today, Earth for All fears despair and counters it with stubborn optimism. Limits to Growth conveyed the dangers of exponential growth with the riddle of the lilypond. Earth for All concludes by comparing the travails of its five turnarounds with « pushing a boulder up a hill ». You can do it. And fear not, a tipping point is on the horizon. We only need to « get the damn thing moving and the force of gravity will help us after that ». Only the stubbornly optimistic belief in a tipping point, however unfounded, turns the struggle into a meaningful one.

Limits to Growth pushed for a system change, in line with its times: Soyez réaliste, demandez l’impossible! That slogan of the late 1960s recognized that if the system should change, really change, then the possibility of change must not be assessed on terms of that system. Earth for All defaults to calls for « system change » without really naming the system to be changed. On the one hand, the report urges you, dear reader, to mobilize and engage as a good democratic citizen. On the other hand, it runs from democratic politics in an oddly reverential paragraph on China’s « state capitalism » that got things done under the mantra of « creating common prosperity ». Is that what today’s « Giant Leap » will take? If Limits to Growth left its politics, as it were, untheorized, Earth for All reduces politics to the art of the possible — Soyez idéaliste, demandez le possible! — counterintuitively depriving the manifesto of all life.

Earth is indeed « for all », but who is Earth for All, well, for? The Club of Rome’s path of action leads via technocratic capitalism, known actors, and international law. Earth for All banks on regimes of trade and finance and on actors like the WTO and IMF, if only they can be nudged in the right direction.

During the WTO’s « Trade and Environment Week » of 2020, members of the organization launched « structured discussions on trade and environmental sustainability » and an « informal dialogue on plastic pollution ». Director-General Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala, since she took the helm of the WTO in 2021, has not tired of stressing that « trade is not just a vital means for diffusing green technology, it is an enabler of greater prosperity and resilience in the face of climate shocks. » With an array of communications and events, the WTO signals that it is fully committed to sustainability, to carbon pricing, a circular economy, and a phasing out of fossil fuel subsidies. The statements of commitments are there, not at the fringes, but right at the centers of power.

The momentum of the alternative globalization movement seems all but gone, partially side-lined and partially absorbed into benign commitments to sustainable growth. We are far from the battles of, say, the WTO Summit in Seattle in 1999. Growth, albeit qualified in ever so many ways, remains the mantra of international law and its leading institutions. On the roster of United Nations Sustainable Development Goals, growth comes in at number eight: « Promote sustained, inclusive and sustainable economic growth ». The WTO touts « going green » and claims a central role in enabling poorer countries’ « green trade-led growth ».

Is something like green growth possible? Can economic growth be decoupled from carbon emissions at a fast enough pace? Impossibly vast yes-or-no questions, toward which vast numbers are vastly crunched; yet I can see no clear answer on the horizon. What does « possible » mean? What is the benchmark of « fast enough »? A maximum of 2˚ C warming? Decarbonize, obviously, but global warming will continue to wreak havoc even if it were possible to avoid the worst. What is « the worst »? The worst for whom? Here I should confess that my own academic field is international law, and I am reminded of my discipline’s expertise, as it were, in coping with disappointment.

International law and its institutions — things like the UN and the WTO — have for a long time been a retainer of hope for justice and an instrument of choice for progressive politics, and not without reason. The Paris Agreement and the global commitment to « pursuing efforts to limit the temperature increase to 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels » are better than nothing. Together with international human rights law they have been leveraged effectively in climate litigation. But the field of international law has simultaneously struggled as its progressive promises have remained unfulfilled. Countries are clearly failing to live up to their commitments under the Paris Agreement, as the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change headlined in 2022. The trouble with international law lies still deeper: often part of the problem, international law has facilitated the kind of economic globalization and extractive, rentier capitalism that is a main reason for the continuous predicament of humankind.

In fact, international lawyers have had a head start in having to deal with disappointment, with the dissonance between progressive aspirations vested in the law and experiences of failure in a recalcitrant reality. They have been there before. They have grown wary when they see that renewal repeats, and insist on « thinking against the box », as David Kennedy, one of the field’s doyens, already put it in the 1990s. Another luminary international legal scholar, Gerry Simpson, recently offered a book-length introspection on the lessons learned from failure in The Sentimental Life of International Law (2021). Before Earth for All hit the shelves, Simpson reflected on the process by which radical, meaningful resistance to extractive capitalism has been domesticated and commodified in international law and its main institutional actors. Resistance, he notes, has become like alternative music: another Spotify genre.

To continue to turn to international law and its institutions with aspirations for progressive change, Simpson suggests, « might invite a certain cynicism not so much from [international law’s] opponents but from within the field itself ». Often it is international lawyers who are not more, but less convinced about the possibilities of transformative change through international law. They carry a collective memory of repeat failure. They are closer to the action and see its messiness, how the law is part of the problem and how it tends to be better at protecting vested interests than facilitating progressive change. How, then, should international lawyers reply (or anyone else for that matter) when they are confronted with the question of what to do? Simpson himself channels Voltaire’s Candide: « All I know … is that we must cultivate our garden ».

« We are fucked » is Extinction Rebellion’s much better slogan than the worn and tattered « it’s not too late ». There is a paradoxical solace that follows from the realization that we are fucked. The future’s openness is made to rest not on stubborn optimism but, far from it, on the inevitability of our fuckedness. Such a slogan inspires, paradoxically, as an antidote to false optimism and artificial smiles. A stubborn optimism that announces itself as being tied « realistically » to possibilities of a different outcome at some point becomes an obstacle to meaningful action and even a betrayal of freedom. Stubborn optimism, that is to say, becomes cruel optimism. The phrase is the late cultural theorist Lauren Berlant’s. Optimism is cruel when something we desire ignites a sense of possibility but makes it impossible to attain. The stubborn optimism of Earth for All risks being cruel because its recommendations have been known and unheeded. There is no reason to believe that this time would be different.

This is as much a problem of genre as a problem of ideology — or, more precisely, it is a problem of temporality: how we think about time. The « it’s not too late » of Earth for All misses what « we are fucked » demonstrates: a genuine grasp of tragedy. The condition of tragedy, at least in its classic, Greek variation, was the certainty of fate. Therein lay its wisdom about freedom. « It was by allowing its hero to fight against the superior power of fate, » Friedrich Schelling wrote, « that Greek tragedy honored human freedom. »

Earth for All announces itself as « a book about our future » and calls the present a crisis. The word is ubiquitous. In its Greek origins, crisis denotes a decision in view of an imminent danger or threat. A crisis is a turning point, a passing exception, that requires an intervention to avoid catastrophe. It locates the catastrophe in the future. Berlant noted that crisis locks in the emphasis on the present and distorts what is structural.

In 2022, this temporality complex was most poignant for me when the Ugandan climate activist Vanessa Nakate received the first « Helmut Schmidt Future Prize », at the Future Festival in Hamburg. The involuntary irony of celebrating the future while Nakate recounted experiences of loss, grief and existential struggle in the past and present only added to the impact of her speech, stunning the audience, myself included, into awed silence and then a standing ovation. It became abundantly clear yet again how speaking of crisis and projecting a catastrophe into the future expresses a situated privilege. Nakate closed her speech with a question directed at Chancellor Olaf Scholz, who was absent on the occasion; he was instead agreeing with other G7 partners to delay the phasing out of fossil fuels: « What will your legacy be? » she asked. « Was werden Sie hinterlassen, Herr Scholz? » She thus submitted him to the judgment of history.

To think of a catastrophe as tragedy rather than crisis is to understand time in a different way. As the philosopher Christoph Menke suggests in Die Gegenwart der Tragödie (The Present of Tragedy, 2005), tragedy’s contemporary salience is that it offers a point of reference against which we can judge ourselves. How would we have acted and how would we act now that we have a sense of how the drama will end? The thought must move into the future and back to the present; the future is folded into the present. Even if Earth for All’s metaphors of reboot and reset suggest circularity, its temporality is linear: It looks towards the future, but the future does not look back at us.

Throughout my readings of this literature, I have kept in mind Victor Frankl’s comparison of optimism to laughter. It appears in a short essay titled The Case for Tragic Optimism (1984), which he added as a postscript to Man’s Search for Meaning (1946), his account of surviving the Holocaust. Frankl asked: What could keep him and others going? How is it possible to « say yes to life in spite of everything »? Saying yes presupposes that life is potentially meaningful even under the most miserable conditions, and that people can make the best of a situation, even in a situation of dread and horror. And that, Frankl reminds us, is what optimism means: the ambition of doing the best — the optimum — under any conditions, regardless of even the most tragic outcome. (Tragic optimism was also Frankl’s answer to an American culture in which, in his words, one is « commanded and ordered to ‘be happy’ ».)

Frankl was a psychiatrist of lasting impact. When he arrived in Auschwitz, he still held on to his first book manuscript, an exposition of his theory of logotherapy. Logotherapy focuses not on power or pleasure as a meaning for life, nor on the past, nor even on the self. It is not retrospective or introspective, but rather attuned to the meanings to be fulfilled by patients in their future. But it does not tie those meanings to promises about the future. With an adroit twist, logotherapy demands that we project ourselves into the future and then look back at our life and the choices we make: « Live as if you were living already for the second time », as Frankl’s most often-quoted line has it, « and act as if you had acted the first time as wrongly as you are about to act now! »

On a t-shirt or a coffee mug, the imperative of logotherapy may look rather similar to « it’s not too late ». But it doesn’t place the future in our hands, nor promise that acting differently makes a difference. It demands that we do the best under any circumstance. It does not deny despair but tackle it, by trying to gain a perspective on the present from future’s gaze back at us. We are acting, in effect, a second time. The temporality is not linear, but cyclical. The optimism is not stubborn, but tragic.

Frankl’s thoughts have resurfaced of late. How to cope? How not to despair? In the Covid era, his account of tragic optimism has made an occasional appearance as an antidote to « toxic positivity », the cloying insistence that everyone should hold tight and even appreciate unexpected opportunities that arise with more leisure time. The solace of recognizing that we are fucked is not limited to climate activism.

Donella Meadows used to have a sign on her office door: « Even if I knew the world would end tomorrow, I would plant a tree today. » Likewise, when Dennis Meadows realized over the decades of inaction on climate change that it would be too late to turn things around, no matter what we do now, the realization led him neither to postures of arresting defeatism nor despair, nor to a vulgar hedonism with Biblical proportions — après moi, le déluge. He lives a tragic optimism that is nourished not by a sense of possibility, but by faith in humanity and an attitude that looks back at life and aims at having made the right choices. It is not about controlling the future. Even if the future were destined, it still matters what the main personages do. As a theory of action, however paradoxical, tragic optimism becomes the only real theory of free action.

The line that separates « we are fucked » from the backfiring logic of « it’s not too late » is thin, even fuzzy. That is itself a curious feature of the time through which we are living. Jem Bendell, a leadership consultant and self-described « strategist », is perhaps not the first person you would expect to suspend his beliefs about our ability to shape the future. But he does ask the readers of his Deep Adaptation (2018) to accept the likely inevitability of collapse, and then invites them to grieve and « to find meaning in new ways of being and acting ». His emphasis is on how we might cope individually and relate to one another socially as the collapse unfolds.

By contrast, Andreas Malm, a prolific author and weathered activist, assumes a tragic posture for the potential it offers to more radical actions of sabotage. An international lawyer’s resignation-gardening, a la Gerry Simpson, does not satisfy. Malm’s deft How to Blow up a Pipeline (2021) reminds his readers that changes are of course possible (unlikeliness must not be hypostasized into impossibility!), but in the same breath rejects the stubborn sermon of « it’s not too late ». It may or may not be too late. If it isn’t, everything depends, obviously, on what we do. But we don’t need the certainty — the feigned or rictus grin — that it is not yet too late. Malm speaks not of certainty and promise, but in the anti-marketing register of trying. He sees an unrelenting need for militancy and real insurrection: don’t shy away — try not to shy away — from the destruction of property and liberal complacency. Seize intersections, occupy mining sites, blow up a pipeline.

Malm’s final chapter pushes back against the « reification of despair » with the power of uncertainty. « No one knows exactly how this crisis will end », he observes. « No scientist, no activist, no novelist, no modeller or soothsayer knows it, because too many variables of human action determine the outcome. » Which means (here following the climate philosopher Catriona McKinnon) that hope can exist. And if it really is too late, well, then radical climate activism will be able to have claimed heroic historical precedents, from Nat Turner to the Warsaw Ghetto uprising, moments when « precisely the hopelessness of the situation constituted the nobility of this resistance. » No matter how late it is, that is to say, it is not too late to become tragic optimists.

Caught between the tired optimism of Earth for All and the expectations of a tragic heroism to which I could not rise, I turned to something different: The eco-socialist utopia of Half-Earth Socialism (2022). The subtitle presents the book as A Plan to Save the Future from Extinction, Climate Change, and Pandemics. Who does not long for such a plan? The authors, Troy Vettese, an environmental historian, and Drew Pendergrass, an environmental engineer, reckon with the insufficiency of once-« progressive » policy proposals: they are either too little too late, or they deal in fantasy.

Like Earth for All, Half-Earth Socialism is built around five points. The first follows the late entomologist E.O. Wilson, who argued in Half-Earth for rewilding half the world. (This argument also pops up briefly in Earth for All but is not pursued, nor would it have fit there.) The other four points are: a rapid transition to renewable energy paired with drastic cuts in consumption by the world’s wealthiest; global veganism; worldwide socialist planning; and the involvement of everyone in decentralized decision-making.

Like Earth for All, Half-Earth Socialism comes in game-form, too. The authors « constructed a Half-Earth socialist planning game to illustrate the difficult trade-offs such a society would have to navigate. » The model is already online at http://half.earth. « With this preliminary model in hand, we try to envision what a complete global simulation might look like, and thus bring us closer to planning the world. » You can practice trade-offs between different choices, parcel a finite planet with finite energy, adjust levels of emission and warming. In its impassioned plea for veganism, Half-Earth Socialism enlists Rosa Luxemburg and many other heroes of the vanguard, while the game lets you calculate: let’s see what that meat does. The ostensibly « realistic » Earth for All had no losers. The more starkly realistic Half-Earth Socialism confronts inevitable trade-offs.

Another difference: Half-Earth Socialism does not cajole us to be better stewards of the earth, exactly, because it recognizes that our species is not really in control — or rather not in control of our own control. The authors recall a biosphere project that was brought down by stowaway ants who multiplied and threw life cycles out of balance. Philosophically, Half-Earth Socialism thus breaks with the enlightenment spirit of seeking to dominate nature. We can be stewards of the economy, but not of the planet. Vettese and Pendergrass hit the nerves of our times: disenchantment is out, re-enchantment is in. Whereas the idea of commoning is suffocated by Earth for All’s tepid embrace, it flourishes in Half-Earth Socialism precisely because it is taken to counter the ruinous dynamics of commodification and alienation.

Yet Half-Earth Socialism does count on big data and advanced algorithmic programming — not to control nature, but to plan the economy in a pointed break from neoliberal orthodoxies: whereas neoliberalism’s premise is that the market, in its infinite wisdom, lies beyond our puny attempts to plan or control it, nature is the unregulatable force here.

In their call for worldwide, central, equitable planning, Vettese and Pendergrass reach back to uncommon heroes and place themselves in interesting lineages. With nerdy affection they explain how the Soviet mathematician and economist Leonid Kantorovich — who won the Stalin, Lenin and Nobel Prize in 1949, 1965, and 1975, respectively — made influential advances in optimizing resource use through linear programming. Kantorovich could then point out glaring inefficiencies in actually existing socialism — a cursed blessing as such insights were not always appreciated by Soviet leadership.

The « socialism » of Half-Earth Socialism is idiosyncratic. Calls for planning as such are no longer unique to the left but embraced with various degrees of awkwardness in outlets like The Financial Times or The Economist. But unlike Earth for All, Half-Earth Socialism does name the system to be changed: capitalism. Less burdened by the wish to be operational, Half-Earth Socialism is liberated in its imagination, and can analyze the present in categories from which the authors of Earth for All shy away. While Earth for All aims at channeling the market and banks on the allocation of resources via price signals, Half-Earth Socialism is certain that socio-ecological transformation requires a degree of central coordination that decentralized market mechanisms cannot provide.

Is it an insult to call a plan « utopian »? The book is a challenge to the left as much as it is a challenge to the center. Vettese and Pendergrass enter an ongoing battle within the left on the utility of utopian thinking itself. « Although the future may appear bleak now, » they write, « it is all the more pressing to imagine utopian alternatives to motivate and mobilize the masses. » (Another of their intellectual heroes is the versatile Austrian political economist Otto Neurath, who pictured utopias not as impossible happenings, but as thoughtful orders of life.) They occupy a different lane, so to speak, from Matthew Huber’s Climate Change as Class War (2022), also published by Verso (a recommendable refresher on a more orthodox leftist approach). Half-Earth Socialism arrives, most intriguingly, at « News from 2047 », a miniature utopian novel unto itself.

The protagonist, William Guest, wakes up in 2047, in a world of natural beauty and splendor, of central planning and socialist democracy. He finds himself in a dorm named after Kantorovich — « Old Lyonechka » — and learns that planetary boundaries now set the parameters of decision-making. The world parliament, which their utopia has placed in La Paz, decides that the global energy quota can be raised from 1.500 to 1.750 watts per person because more renewable energy has become available. People work only four days a week, in shifts and without specialization, sharing the more and less pleasant chores. Digging a ditch for water management is recognized as the worst task, but as the protagonist picks up a shovel, he « quickly fell into a rhythm ».

This utopia winks back at an earlier one: William Morris’s News from Nowhere, published in 1890 with a protagonist of the same name. In both utopias, humans are at home with themselves and with their natural habitat. Both tend toward an agrarian pastoral, and humans gain meaning and pleasure from their work. Morris’s William Guest is told, in the end, to « go back again, now you have seen us …. Go back and be happier for having seen us, for having added a little hope to your struggle. » Half-Earth Socialism’s William Guest is eager to « report to class first thing tomorrow morning » (for such education is key to building a socialist society), but he will only be in 2047 for one day, and as that day draws to a close,

he was surprised by his tears… The next morning he knew, he would awaken back home, in the world as he’d left it. … He felt something like hope start to grow. « If others can see it as I have seen it, » he said to himself, in something like a prayer, « then it may be called a vision rather than a dream. »

The year 2047 is chosen to counter the would-be centennial of the neoliberal movement founded at Mont Pèlerin in 1947. Guest thus returns to aid in the struggle against neoliberal capitalism.

Half-Earth Socialism is offered in the spirit of a « humble utopia ». The authors frame it as decidedly plausible, indeed realistic. It comes after a great deal of theoretical preparation, but the point is less to be operational or even pleasant than to be bracing: to describe a world that would actually meet the truest and starkest scientific measures of the moment, with all of the unfamiliarity that such a world would entail. Energy quotas, travel allotments, veganism, re-schooling, socialism’s stereotypical love of meetings — all are necessary to stay within planetary boundaries.

Half-Earth Socialism sketches a dramatically transformed future that may only appeal to a subset of the already-convinced. But I am glad, in any case, for the bracingness of its not-at-all humble utopia. And I would humbly submit that Half-Earth Socialism is in many ways what Earth for All could have been. It is, perhaps ironically, the truer heir to Limits to Growth and a more satisfying way to mark its anniversary. It resumes a path that Earth for All abandoned. Looking back upon our present from 2047, Earth for All would appear sad and quaint, the product of a waning zeitgeist: « After decades of environmentalists’ championing ‘win—win’ solutions for both business and nature, » Vettese and Pendergrass write, « it became clear that making unprofitable decisions was where true freedom lay. »

Looking back at 2022, people in the future will probably chuckle at the postulation of win-win situations, and perhaps also about the supposition that eco-socialist utopias would succeed. Perhaps they will dust off our utopias as Vettese and Pendergrass dust off Morris’s News from Nowhere. What they’ll find, at least, is an « honest reckoning » that resists the temptation of empty promises.

There is one thing I keep on coming back to as I try to look past the stack of it’s not too late’s. I am haunted by Earth for All’s comparison of our current travails with the act of pushing a boulder up a hill. Haunted, or baffled, by the perfect, inadvertent farce of it. They are narrating the story of Sisyphus, with blithe oblivion. The real Sisyphus finds a kind of peace. How goofy, then, to imagine that Sisyphus was happy not because he realized the existential tragedy of his situation, but because he believed in something like a tipping point? Cheer up, Sisyphus! You can do it!

- For example, a greater world population and greater wealth leads to greater demands for non-renewable resources. That relationship is not linear: A change in one variable (wealth) does not have a steady impact on the other variable (resource use). If a society is already very wealthy, additional wealth still means greater demands on resources, but at a lower marginal rate when compared to a less wealthy society. The relationship is not one-directional either but marked by feedback loops: Wealth and population growth do not only impact the demand for non-renewable resources, but the inverse is also true, they are also influenced by the demand for and scarcity of non-renewable resources. Plus, resources are not the only relevant factor for either wealth or population growth. And around we go. There is no beginning or end. ↩︎

- An example: « As everyone who works methodologically and professionally in foresight knows, the future does not exist yet, so there can be no evidence-based data from the future (until we get there). ↩︎