On Paleolithic painters & speculative criticism.

To muffle passenger chatter on this French train, my travel companion chooses the « cavern » setting on his noise-cancelling earbuds. Its subterranean acoustics allow you to devolve for a little bit in your own private grotto. His selection of this setting is no accident: we’re coming back from the Vézère Valley where we’ve just seen the Cro-Magnon rock shelter and circa 18.000-year-old paintings in the Font-de-Gaume cave, in whose gift shop I bought a copy of George Bataille’s Lascaux ou la naissance de l’art. In this train, my troglodyte lover is next to me in his man-cave and I am next to him spelunking deep in Bataille’s underground. We are feeling Paleolithic.

Like anyone who gets the chance to see light and shadow cast across the three-dimensional-seeming bison, horses and other earthly creatures in the Magdalenian depths, I was spellbound by them. Our guide added to this effect as he spoke with soft conviction about the beauty of these staggeringly old, carefully rendered traces of manganese oxide and calcite and red ochre. Afterward, as we emerged from the cave as though birthed anew, the lasting enchantment kept pushing me to write out all the reflections spurred by this strange experience. But these reflections were as shapeless and slouching as the shadows in the dimmer corners of the cavern. To give them a firmer form and relevance, I needed to attach them to something newer, something more concrete. Why not review some new book that might relate to the early days of Homo sapiens as a pretext for unfurling my own dazed wonder about these prehistoric pictures?

Somehow, cave art destabilizes the observer.

Many book reviews are just excuses for critics to write about what they already happened to be thinking about, which is the case here. There were a number of recent books that would have allowed me to dwell longer on (and in) my cave experience. Such a bibliography might include John J. Shea’s The Unstoppable Human Species: The Emergence of Homo Sapiens in Prehistory (Cambridge University Press, 2023), Deborah Barsky’s Human Prehistory: Exploring the Past to Understand the Future (Cambridge University Press, 2023), Maria Stavrinaki’s Transfixed by Prehistory: An Inquiry into Modern Art and Time (Zone Books, 2022), or the earlier Jean Clottes’ What Is Paleolithic Art?: Cave Paintings and the Dawn of Human Creativity (University of Chicago Press, 2016). The French writer Pierre Michon’s novel Les deux Beune (Verdier, 2023) is set in the caveland between Les Ezyies and Montignac, where I’d just been, and thus could have offered a setting for my reflections. But for various reasons too dull to describe here, I shelved these books for future reading and chose a different one instead. Trenton Holliday, a paleoanthropologist at Tulane University in New Orleans, just happened to have published a new book called Cro-Magnon: The Story of the Last Ice Age People of Europe this year with Columbia University Press, and in flipping through its pages, I quickly recognized that it could fill in many of the blanks in my knowledge about early Homo sapiens while also taking the kind of creative liberties that the species’ early art-makers might appreciate.

Before getting to Holliday’s book, I want to offer a few general observations about how people tend to write about prehistoric art, which I’ve drawn from older classic books and essays on the subject and which I’ll illustrate later with some examples. First, such writers tend to put themselves in relation to this art, especially in its cave-wall iterations. Their reflections get very autobiographical very fast. Second, such writers tend to zoom out from the particular to the universal in a mode best described as existential bewilderment. Somehow, cave art destabilizes the observer, who up until then had lived rather comfortably in their understanding of the order of things and their own place in this order. Finally, such art imposes a very specific epistemological mode on the beholder. That mode is speculation. Alongside the zoom-out from self to universe, a guessing game unfolds, with lots of « mights » and « maybes ». The vocabulary of cave art writing includes all the markers of hypothetical thinking. What would art look like today if these first aesthetic yearnings had never been discovered? What if these images were not art at all but were instead what remains of some magic ritual whose gestures and meanings have been lost?

For many philosophers, scientists, and artists, the origin of art marks the moment we truly became human. A cave painting is a trace left by a being who had only shortly before shed its animality to don a new, imaginative mantle. Homo sapiens, a creature in whose brain new faculties were quickly sprouting, could not only make its creativity visible in the form of tools or representations; its first cognitive strivings suggested wilder things to come, from abstraction to algorithms. Taking in those early signs pointing to a future of atom bombs and calculus, spaceships and postmodernism, a first reflex is to braid oneself into that lineage. I am he as you are he as you are me and we are all together. What is the nature of this relationship? Are we contiguous or continuous? They are dead, but what of them lives in me still? Are my « advanced » skills the apotheosis of their first aspirations or — as my art skills attest — am I the impoverished variant of a genius prehistoric painter?

When I saw these cave paintings in real life, I was shocked to discover that they do not resemble simple children’s drawings but require an imagination that might have been significantly more elaborate than our own. Those early artists were creating not only art but the tools necessary for making it; they had no canon to imitate, no schools where they could be trained. Potentially anything — any material, any space, any object — could be used to create those unprecedented forms that would later be called art. We’ve stifled much of that early creative genius with civilization. Despite the fancy, new-fangled things that people in our lineage are making now, it is clear something has been lost along the way. The most bewildering part is the span of time that separates us from these ancestors. One starts to daydream about the untaken paths of our species, about what one individual life has to do with life as a category, and to worry about what will be left after our finitude asserts itself. One feels a sudden urgency to know more about those who set us on our trajectory. But there is no one to tell us who drew these pictures, why they drew them, or what they mean. We can only speculate.

The word Cro-Magnon sounds better in French.

Trenton Holliday’s Cro-Magnon is not exclusively about cave art. The book sits at the crux of a number of disciplines — archaeology, paleontology, genetics, geology, anthropology, and history — exploring everything related to Cro-Magnon, which « was for many years a widely used name for the earliest modern humans in Europe ». Holliday tells us this term has become somewhat colloquial, with many opting now for other denominations, such as Early European modern humans (EEMH), which describes different groups and their descendants who migrated from Western Asia in the Upper Paleolithic era. The name Cro-Magnon was given to those bodies found buried at a rock shelter in Eyziesde-Tayac. (« Cròs » means creux or hollow in Occitan, and « Magnon » was the owner of the property where the skeletons were found.) As we walked past the Musée national de Préhistoire near the shelter, one of the local restaurants had on their menu not only the croque-monsieur and the croque-madame, but the croque-magnon. The word Cro-Magnon sounds better in French, just as Neanderthal sounds better in its original German (Neander + Tal = Neander Valley, in North Rhine-Westphalia; the valley was named after Joachim Neander, a seventeenth-century pastor and composer of hymns). Holliday’s book includes everything that archaeologists, paleontologists, geneticists, and bioanthropologists have to say about Cro-Magnon’s body, behavior, and objects. Even though its scope is much broader than cave art, the book nonetheless follows the above-mentioned patterns. The autobiographical impulse is palpable in those early pages. In a section that starts with « Who am I? », we learn that Holliday was a « quirky kid » who became a « quirky adult »; that he has been a fossil hunter since childhood and that at age eight, his mother told him « about the discovery of ‘Lucy’ — a 40 percent complete, 3.18-million-year-old Australopithecus afarensis skeleton — at the time our earliest human ancestor. » He explains from the beginning why he has put so many personal anecdotes from the field in his book: « Throughout this book are vignettes from my time researching fossils; through these I hope to give you a feel for what it’s like to be a member of the cadre of people who study human evolution. » It is something quite special for a reader to behold the beholder, to watch Holliday look at fossils, flint tools and mobiliary (portable) or parietal (cave wall) art. His perception of the objects — tinted by his enthusiasm and wonder — is our filter.

Holliday’s intense joy for his subject makes me remember my own early points of contact with the prehistoric world. A caveman diorama in a natural history museum in Fort Worth, Texas, that seemed like some strange dream; my undergrad anthropology class assignment to make our own projectile points and hand axes from stone and to identify all the bones of the human skeleton; my dad’s huge fossil collection and his rock tumbler that could make the most boring pebble look like a precious jewel; endless refrains of the fireside song from the movie Caveman (featuring Ringo Starr) in the early eighties sung with my brother; a visit with my grandparents and cousins to the Creation Evidence Museum in Glen Rose, Texas, with exhibits showing humans and dinosaurs living alongside peacefully under a pink sky. I remember Inner Space Cavern in Georgetown, Texas, with its labyrinth of stalagmites and stalactites artfully lit by hidden colored bulbs. And a viewing in high school of the cult classic Altered States (1980), Ken Russell’s body horror film, made me really believe you could turn yourself into a caveman by taking the right drugs.

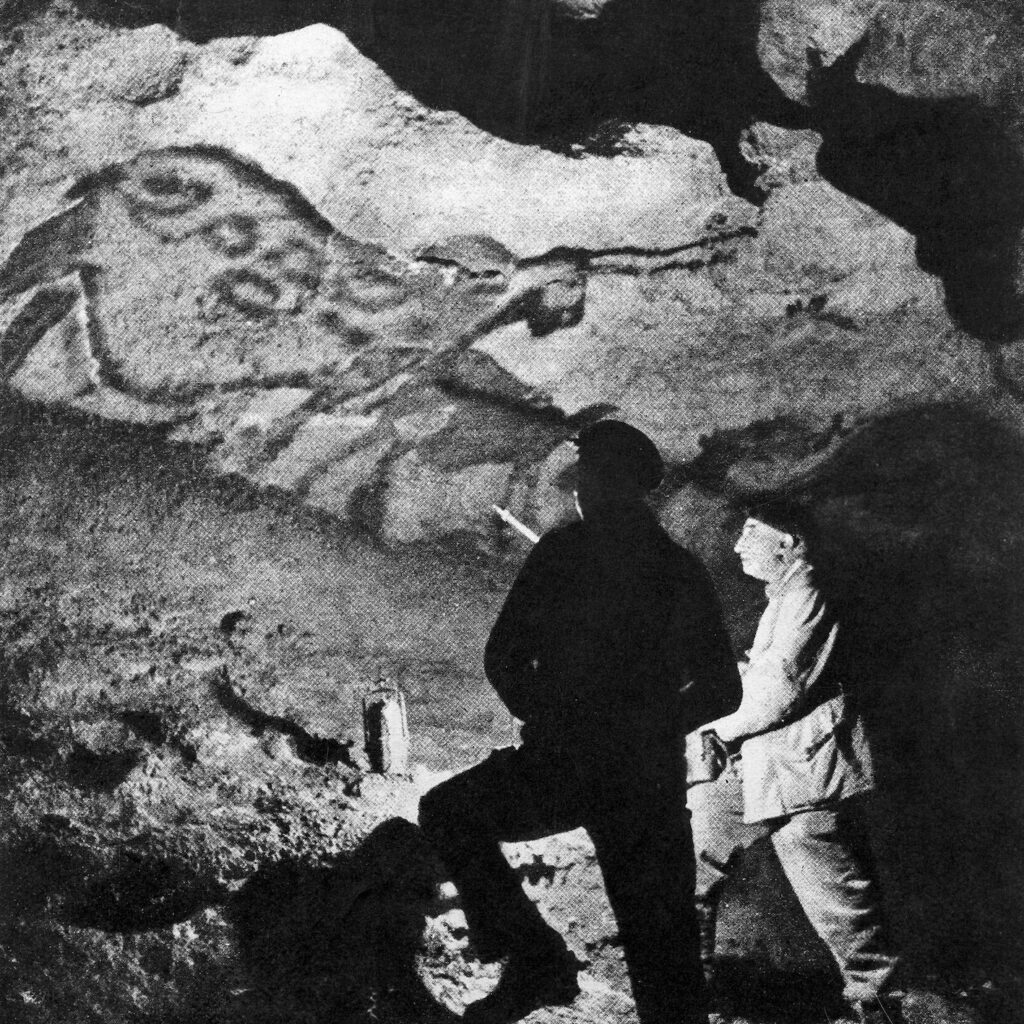

These and other memories had flooded back, too, in Font-de-Gaume, as the guide lit up various parts of the cave with low lights, a flashlight or a laser pointer. Each kind of light served a different purpose. The low lights kept us from tripping in the narrow passes — one of our fellow visitors whispered to the guide that she had claustrophobia, which he subdued with warm reassurances — and revealed to us the vague forms of a reindeer or a bison or a wooly rhinoceros as the path grew wider. These soft lights made the cave feel like an art space, a theater, or a holy sanctuary. In French, the words for various spaces inside caves, such as la galerie (gallery), la grande salle (great hall), la nef (nave), or l’abside (apse), strengthen these associations.

Light brought the walls to life.

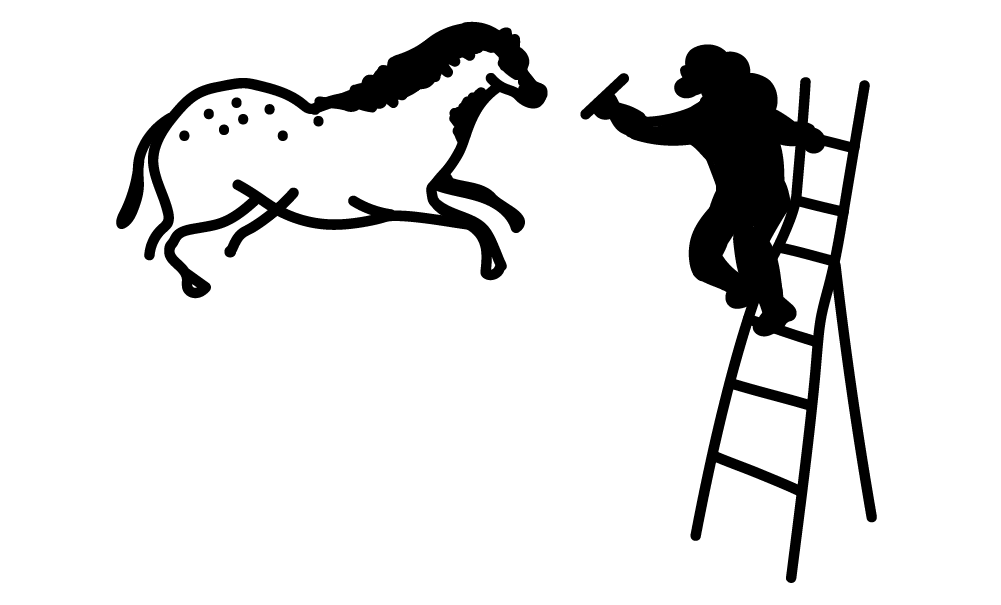

His flashlight, on the other hand, revealed one of the biggest surprises that had remained hidden until he flipped on its switch: those who drew these animals used the natural contours of the wall to give them three dimensions. This kind of light probably resembled that of the Tecalemit flashlight one of the boys who discovered the Lascaux paintings on 12 September 1940 used to cast light on its walls for the first time in thousands of years. Here, in Font-de-Gaume, the bison’s imposing hump jutted out of the wall and seemed to move through space as the guide ran light across it from different angles. He asked us to imagine the flashlight as a torch, whose flicker would have animated the figures even more. The flashlight also revealed etchings in the stone. Held at the right angle, suddenly a nick in the rock became a carved-out eye, and the curl of a horn snapped into view. Light brought the walls to life. Holliday explains how this effect was achieved:

The artists in these caves created the illusion of three-dimensional animals through several techniques: (1) using the contours of the cave to « suggest » the shapes of animals, (2) applying the techniques of « vanishing point » perspective, and (3) employing a high degree of shading variation, often scraping away at the wall before painting to create a whiter surface for greater contrast.

Werner Herzog’s 3D film Cave of Forgotten Dreams (2010), about the Chauvet Cave paintings discovered in 1994 in southeastern France, dwells on this feature of much of the earliest cave art made in the Aurignacian (30-32.000 years ago) and Magdalenian (12-17.000 years ago) eras. The film’s three dimensions transform the cinema space into a cave. The spectator is no longer at the movies; she is suddenly in a chamber in the ground. Moving light across the cave’s walls, Herzog narrates:

For these Paleolithic … painters, the play of light and shadows from their torches could possibly have looked something like this. For them, the animals perhaps appeared moving, living. We should note that the artists painted this bison with eight legs, suggesting movement, almost a form of protocinema. The walls themselves are not flat but have their own three-dimensional dynamic, their own movement, which was utilized by the artists. In the upper left corner, another multi-legged animal. And the rhino to the right seems also to have the illusion of movement, like frames in an animated film.

Caervids, bovids and horses

painted on a cave wall

CHRISTY WAMPOLE

Caervids, bovids and horses painted on a cave wall

Caervids, bovids and horses painted on a cave wall. Courtesy of Wellcome Collection

The temptation is to reach out and touch it.

I had always thought that Plato’s allegory of the cave was the first gesture toward a cinema to come, but it turns out that the early Paleolithic painters had beaten him to it by tens of thousands of years. The trope of cave-walls-as-cinema-screens was kept alive by Herzog’s film and was revived again in an art installation I happened to have stumbled upon while writing this. Unlike most caves, it was in Berlin, you needed an elevator to access it and it was full of art hipsters. The space of Hito Steyerl’s Contemporary Cave Art exhibit at the Esther Schipper Gallery in April and May of 2023 somewhat resembled a cave — but without the echoes, the damp chill, and the fragrance of minerals — and presented video installations and glowing orbs filled with plants. There were sensors inside the orbs that reacted to human presence and caused sparks of light to billow on the screens. Steyerl, I think, does try to draw an explicit line between the Aurignacians and algorithms, wondering aloud what is primitive in us and what was modern in them. She shows that in an otherwise pitchblack space, light — in the form of a torch, a pit fire, a flashlight, a screen, or a glowing orb — has maintained its power over our senses and moods, still able to put the brain in a particular state of wonderment after all these years.

The red light of our guide’s laser pointer distracts me from Steyerl’s paleodigital psychedelia and brings me back to the real cave art in Fontde-Gaume. The laser pointer traced the contours of what the guide called a main négative (negative hand), the shape of a hand made by placing it on the wall and blowing pigment around its edges. This was the culmination of the visit: a small human hand waving at us through millennia. More than any other shape on the walls, this one conjured a ghost in the room. The temptation is to reach out and touch it, to fraternize with the dead.

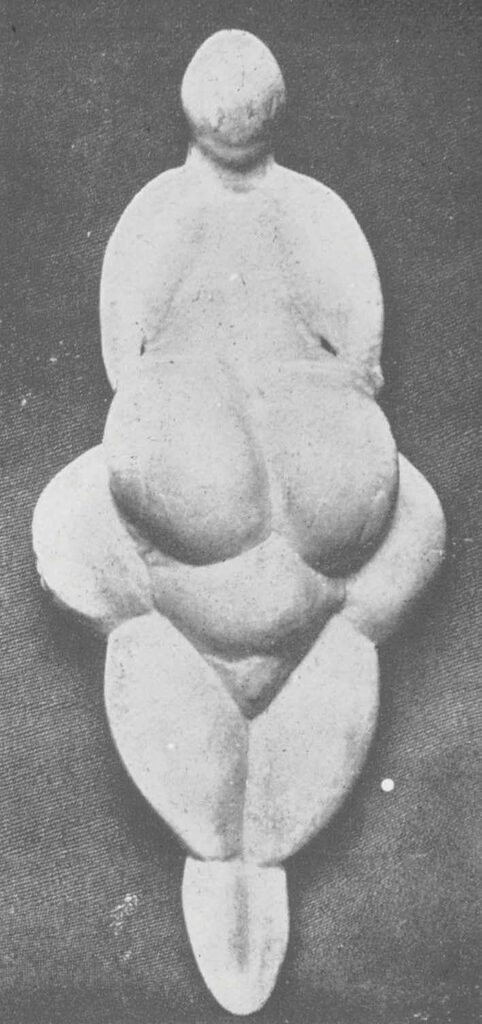

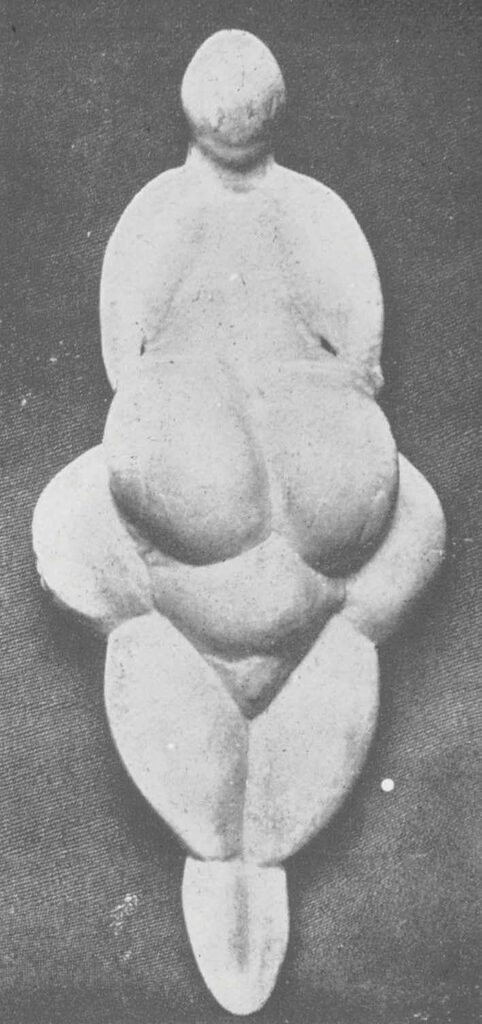

The experience of dwelling in a cave, if only for a little while, calls you to write about it. Clearly, this was the case for Holliday. He is just the latest in a long line of people who felt the need to respond to prehistoric objects with reflections on personal experience. Georges Bataille (1897- 1962), too, uses autobiographical anecdotes in his writings about prehistoric art. There were always questions about whether he could be labeled as a scholar — someone who usually tries to erase any signs of subjectivity in their academic writing — or as something much wilder. Roland Barthes asked the following questions about him: « Is this writer a novelist, a poet, an essayist, an economist, a philosopher, a mystic? The answer is so uncertain that handbooks of literature generally prefer to leave Bataille out. »1 In his lecture « A Visit to Lascaux », Bataille tells us what a dick Sartre was to him: « […] on a personal level, I don’t get along with Sartre, and if I wouldn’t say that we have our daggers drawn, it is because philosophers don’t have daggers. In any case, in his writing Sartre rarely misses an opportunity to talk about me in a snippy way. This has gone on for about ten years and I’m used to it. » The only purpose of this autobiographical departure is to put distance between Bataille’s way of doing philosophy and Sartre’s, a methodological difference he emphasizes up front before offering his personal reflections on the art of prehistoric peoples. He reminisces about his first childhood drawings in an essay called « Primitive Art »: « Personally, I remember having practiced such scribblings: I spent an entire class coloring the suit of the classmate in front of me with my pen. » In an essay on the Lespugue Venus — a nude female figurine between 24.000 and 26.000 years old, found in 1922 in the foothills of the Pyrenees — he tells of the overpowering experience of seeing it in real life: « Most of the photographs published of it are not engaging, but, if I may say so, the day I saw it in the glass case at the Musée de l’Homme, I was no less dazzled than I had occasionally been when contemplating consecrated masterpieces. »2

Perhaps more quickly than others, Bataille abandons the autobiographical for the aforementioned mode of existential bewilderment. This is evident, for example, in a lecture he delivered on 18 January 1955, which mentions at the start that the atom bomb currently threatens human existence, but then quickly pivots: « I do not intend to talk to you about our eventual demise today. I would like, on the contrary, to talk to you about our birth. I am simply struck by the fact that light is being shed on our birth at the very moment when the notion of our death appears to us. » Or this one from his essay « The Cradle of Humanity »: « From the depths of this fascinating cave, the anonymous, effaced artists of Lascaux invite us to remember a time when human beings only wanted superiority over death. » These pronouncements are signature Bataille. Whether he is describing the animal forms painted deep in the cavern shafts or the objects residing in various museums across France, excised from their original context, he always writes in the mode of existential bewilderment: everything is about origins and ends, life and death, Alpha and Omega.

Holliday’s tone is lighter. His book is driven by an enthusiasm for life and knowledge, not by the looming specter of mortality. One perceives his avidity for his subject when he tells of « perhaps the most exciting revelation in recent years regarding the consumption of plants by the Cro-Magnons »: some microscopic plant fragments found still attached to the pestles that had ground them down 28-33.000 years ago. Stories of his mentors, his digs, his own finds and those of researchers he has never met — the existence of prehistoric people is very tightly bound to his own existence throughout the chapters.

Rather than agonize over all that we will never know about Cro-Magnon, Holliday delights in these chasms. The book abounds with perhaps, piles of question marks, and the most exasperating phrase of all for those seeking certitude: almost certainly. From the first pages, he fills in the unknowns with fiction, something unexpected in a scholarly book on ancient Europeans:

Venus of Lespugue,

statuette 26.000-24.000

years old

Venus of Lespugue

Venus of Lespugue, statuette 26.000-24.000 years old.

Lar and Mil were dizzy with adrenaline, their palms slick with sweat. Today they were taking part in their first reindeer hunt. For as long as they could remember, they had been honing their skills throwing spears; thirteen-year-old Mil threw spears with deadly accuracy, and twin Lar was not far behind. Silent and nervous in their blind, they waited for the signal to attack — a whistle from one of their cousins. They remained motionless in the cold autumn air so as not to scare away the approaching herd.

Holliday makes up a whole story about these fictional twins and their family’s attempt to survive the winter. After the scene is set, he interrupts to give the reader an idea of what he is trying to do:

Today Lar’s and Mil’s people are colloquially known as Cro-Magnons — people physically indistinguishable from you and me who made their living hunting and gathering in Ice Age Europe. […] All we know about them we have learned from studying their skeletons and the art and debris they left behind as they went about their lives. Although the story of Lar and Mil is a product of my imagination, no doubt there were people in Ice Age Europe who lived lives much like those depicted here. This book tells their story. It includes vignettes like this one, but it’s primarily about the scientific investigation of these ancient people, written by someone who has studied them for more than three decades.

These people should be made legible to us.

The vignettes are quite weird. I imagine that this kind of fabulation could ruffle the feathers of his fellow scientists and other professional truth seekers. Even those open to fabulatory experiments — I’m thinking of Saidiya Hartman’s « critical fabulations »3— might have qualms about various anachronisms or cultural assumptions in his vignettes. For example, Holliday’s depiction of the twins’ cool grandma — she speaks multiple languages and does a lot of joking and teasing, and behaving somewhat like a sassy American sitcom granny — requires such a suspension of disbelief, one might never recover it. The grandma — as an archetype, as an institution — took millennia to solidify into its modern iteration(s), and the grandmother of Lar and Mil bears features of this modernity. Rather than engage in such scholarly nitpicking — I’m certain he anticipated this from some readers and decided to take a chance on doing something unconventional anyway, the kind of risk I always appreciate — it is more interesting to reflect on what is achieved through the staging of such scenes and the invention of such characters. Holliday’s main goal is to remove all of the temporal debris that separates us from them. To do so, he tries to make what is remote more familiar. These people should be made legible to us, his book seems to argue. But isn’t one of the most captivating things about early Homo sapiens that, as the first draft of humanity, they are free of the commonplaces and stereotypes and habits and historical heaviness of their descendants? In short, our baggage? I find it almost impossible to inhabit the subjectivity of a baggage-free Homo sapiens. In the vein of Thomas Nagel’s « What Is It Like to Be a Bat? » we might have to admit that we cannot know what it’s like to be a caveman, only what it’s like for us to be a caveman.

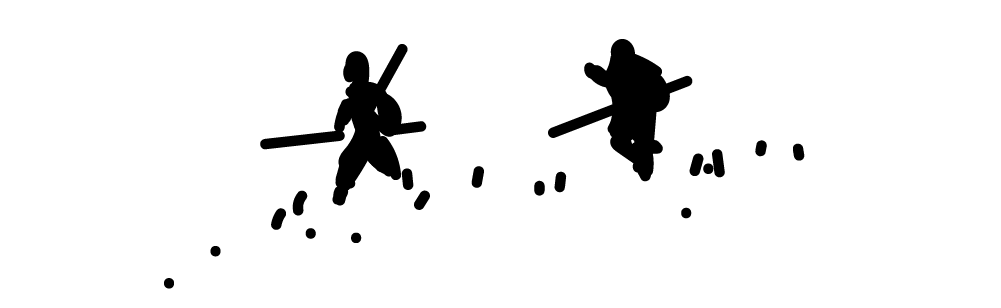

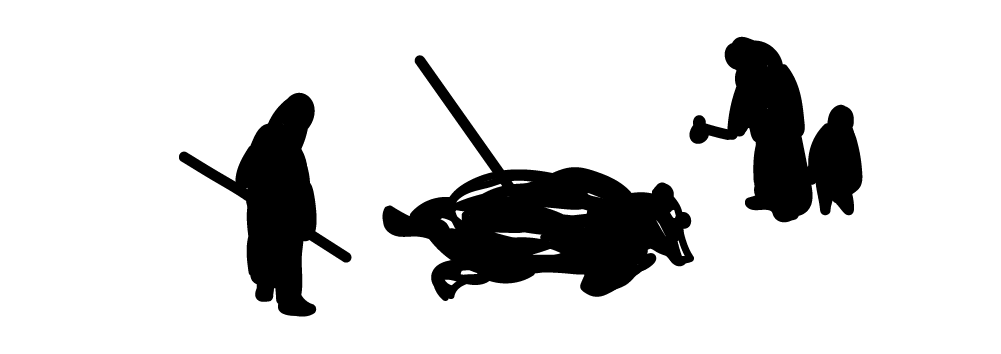

This hasn’t stopped people from trying. Holliday describes an attempt in France to reconstruct the daily life of prehistoric communities:

About eight kilometers (five miles) outside of Les Eyzies one finds the delightfully campy Préhisto Parc, with life-size dioramas of Paleolithic peoples engaged in a variety of behaviors, such as sneaking up on a woolly rhinoceros (« I’ll take ‘Things I would never do’ for $1.200, Alex »), burying their dead, or creating art, all set in lush natural surroundings and guaranteed safer than Jurassic Park!

He is right that attempts to stage Paleolithic life — like the caveman diorama I’d seen back in Fort Worth in my youth — always have a certain campiness to them. All the tropes are there: the figures are stooped and hairy and grunting, far less evolved than Fred Flintstone or Barney Rubble. They carry clubs, wear animal skins, and drag their wives around by their hair. But the people who staged these scenes are earnestly trying to open up a pocket of Paleolithic life in our here and now. Their efforts only seem absurd because the task they’ve taken on is an impossible one.

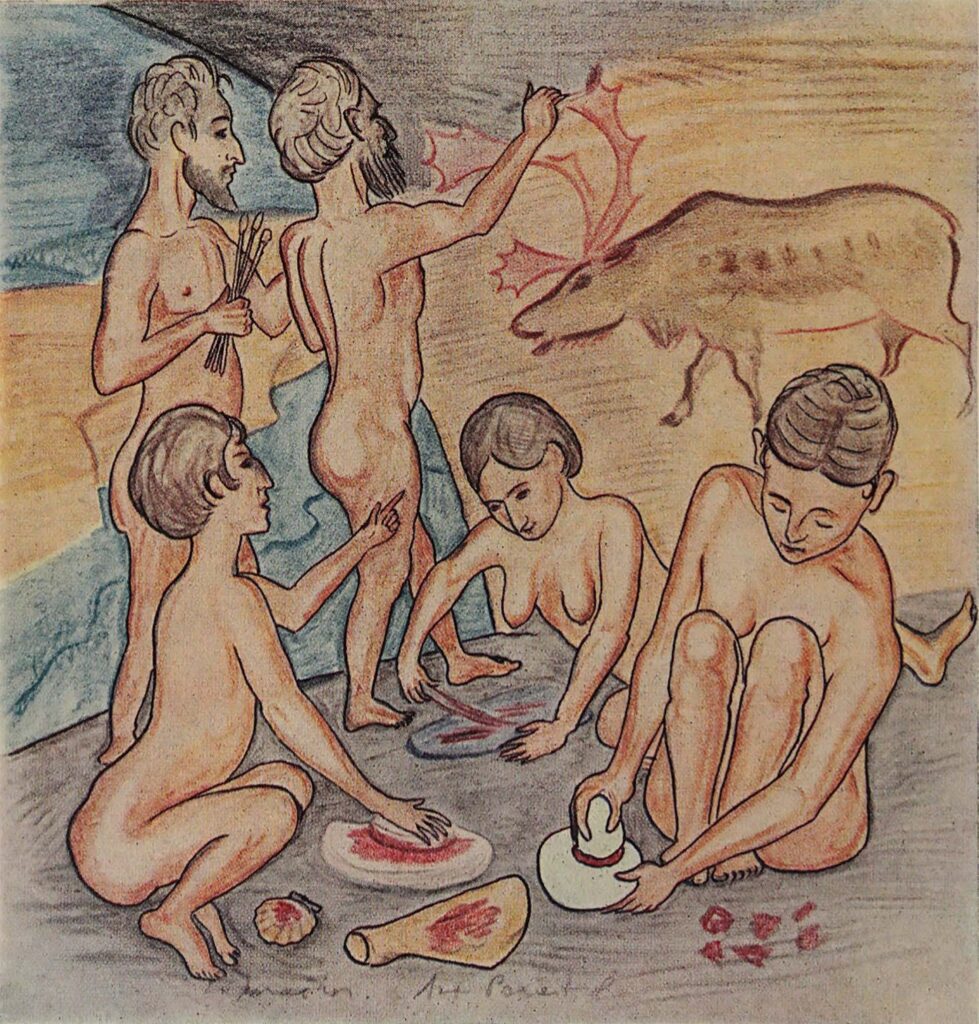

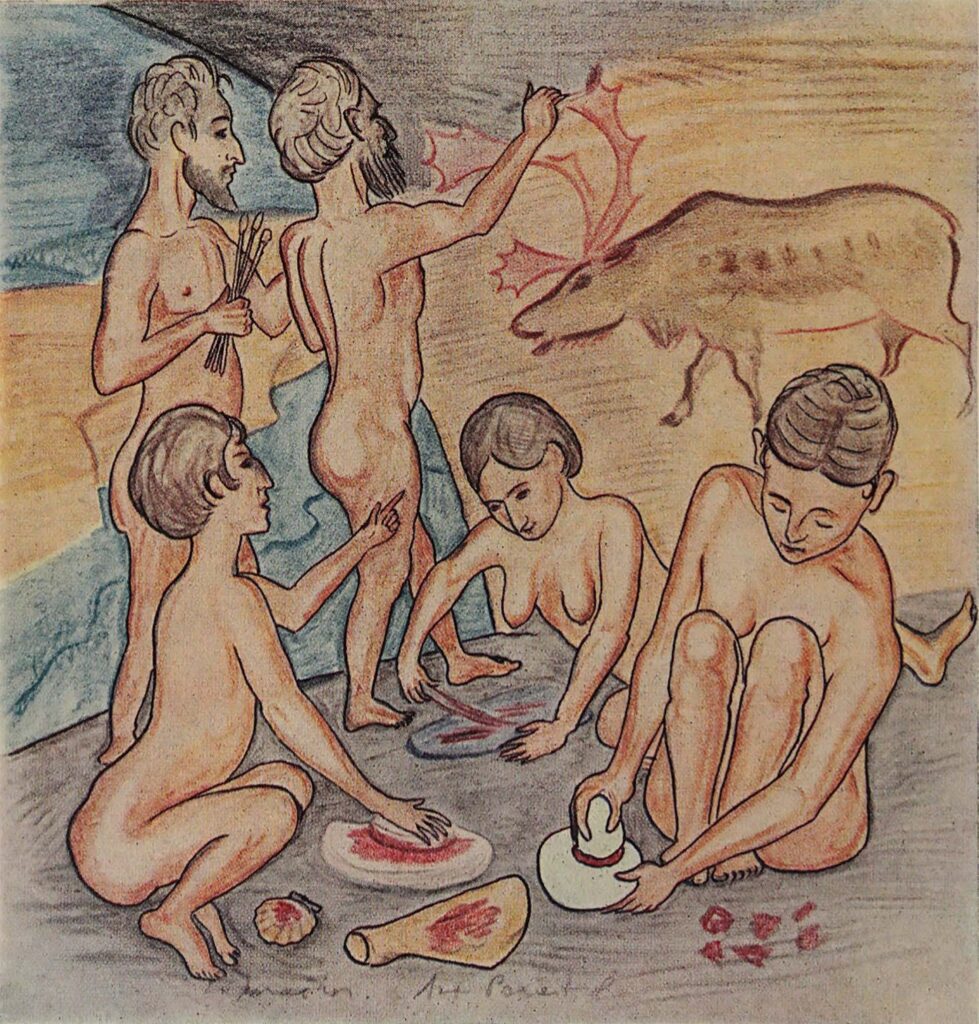

Henri Breuil, Scene from the

Stone Age, 1949

CHRISTY WAMPOLE

Henri Breuil, Scene from the Stone Age, 1949

From Beyond the Bounds of History: Scenes from the Old Stone Age (1949), by Henri Breuil.

An illustrated version of this kind of prehistoric mise-en-scène was offered already in 1949 by Henri « Abbé » Breuil (1877-1961), a French Catholic priest and archaeologist. He was not only the first to produce quite accurate renderings of the cave paintings in Lascaux and Altamira (in Spain) but also used his imagination to portray the daily life of Paleolithic peoples in illustrated form. His book Beyond the Bounds of History: Scenes from the Old Stone Age (1949) presented thirty-one of his color illustrations showing people chipping flint, hunting bison, working bone and deer horn, preparing skins, conducting a funeral ceremony, trading with ornamental shells, painting rocks, and engaging in other daily activities. Abbé Breuil’s drawings have a naivety (and campiness) about them, like a child’s coloring book filled in neatly with vibrant crayons. To come up with such tableaux, one can see that Breuil was limited to building stories around all the objects that had been found up to that point. How would more updated knowledge about these early peoples — acquired through DNA or 3D morphometric analysis — have altered Breuil’s speculative drawings? It is an interesting idea to imagine these stories morphing before our eyes as the scientific record fills out. Whether in the form of fictional vignettes, illustrated scenes, dioramas, or re-enactments in documentary films, the life of prehistoric people gets tried out again and again across media, as though the urge to give these ancestors an afterlife through representation were programmed in our DNA.

The fictional vignettes are not the only sites of speculation in Holliday’s book. In the chapter « Cro-Magnon Art, » an invented tale about « Garman, the Keeper of the Stories » then yields to this pronouncement by Holliday:

He’s right about the elusive nature of meaning when it comes to art of all periods. Why is the Mona Lisa smiling? What is going on with the anamorphic skull in Holbein’s Ambassadors painting? What the hell did Hito Steyerl’s installation mean? Such questions feel somewhat foolish, especially since Barthes articulated his position that it is the beholder who brings meaning to a piece of literature or art. Any attempt to glean meaning from art, Holliday suggests, is a game of speculation, which should be fun, not frustrating. Let the speculation begin! he shouts.

But it is worth pausing here to reflect on the differences between speculating about an object before and after (art) history began to exist. Perhaps the eagerness to speculate about prehistoric art stems from the fact that this art was not flooded with the sorts of influences that arrive with recorded history. Yes, the artists were undoubtedly responding to what was around them, to what they saw others making, to forms they’d seen somewhere else before. But without all of the memory-extending paraphernalia that history floods the world with — written accounts, critiques, the establishing documents of aesthetic schools, catalogs of techniques and materials, the literatures whose characters and stories find their way into visual representation, bureaucracy, and all other evidentiary stuff left from the past in written form — the memory pool these artists were wading in was shallow. Speculation about the objects they’ve made is an occasion to wade with them through a less full world. To do so requires a thought experiment that empties life of all that has come since those remote times. To do it right, we have to become something other than ourselves, to erase all that has accumulated in that process that has often been called civilization. And because such forgetting, such suppression, is impossible, the first step of this game of the imagination is a faux pas.

Speculation began as soon as cave paintings were discovered. The most famous story of such a discovery is that of Lascaux, an origin always retold with extreme vividness (and, sometimes, fantasy) by anyone writing about it. The simple version: on a Thursday in September 1940, a group of teenage boys and a dog accidentally discovered the cave. (A great detail: The dog’s name was Robot.) Bataille’s text « The Discovery of the Cave » relates several versions of the story, which was a fantastic distraction in the press for Europeans in the midst of a tragic war. Did the boys go exploring because of what they’d heard about this hole left by an uprooted tree? « An old woman, who had once buried a dead mule there, had long maintained that the hole was the mouth of a medieval underground passage » leading to a « little chateau. » Bataille continues: « The other version, according to which the youngsters, off on a hunt, followed their dog down into the hole, seems to have been invented by journalists to whose questions the lads replied ‘yes’ without attaching much importance to what they were saying. » An astounding discovery, which instantly elicited countless questions: How old were these pictures? Who made them? Were they authentic? Were the paintings made to tell stories? To celebrate or commemorate? To pass the time? To leave a trace?

In his essay « A Meeting in Lascaux, » Bataille contests the assumption that what the cave painters were making was even art. What if, as many have hypothesized, the images were part of a ritual meant to manifest the four-legged food in the upcoming hunt? He writes, « These hunters of the Dordogne would better understand a housewife from Sarlat buying meat for lunch from a butcher shop than they would Leonardo da Vinci […]. » Abbé Breuil, the aforementioned visual fabulist, was one of the first to promote this theory. There is a problem with it though, as Holliday points out:

Holliday enumerates multiple interpretations of the paintings and many prehistoric art-like objects. Regarding some small « lifelike carvings, most in ivory, of animals » found in the Swabian Jura, he writes, « interpretations of these objects as totemic symbols are unprovable but certainly possible. That said, they just as easily could have been toys for children. » The Lion Man, an anthropomorphic lion carved in mammoth ivory found in Germany, gives rise to a series of questions from Holliday:

Lion-Man is the oldest representation of a mythical creature found so far, and I cannot help but wonder who he was. Was he a god or a magical being? Was he a powerful shaman who had passed on to another world or a hero of legend? How widely was Lion-Man known? Would Aurignacian people in the Vézère Valley, or even as far away as Portugal, have immediately known who he was, or was his fame much more localized within the Upper Danube Valley? Finally, could he simply represent a person wearing a lion mask?

The many prehistoric Venus figures found throughout Europe have often been interpreted as fertility symbols due to their exaggerated sexual features, but Holliday entertains other possibilities: Do they represent an « Earth goddess »? Are they « three-dimensional self-portraits of their own bodies » made by women? Are they « paleo porn »? He writes: « Whatever their function(s), the fact that this cultural tradition continues over such a broad swath of Eurasia for so many thousands of years is amazing to me. I can think of few cultural motifs today with such longevity, with the possible exception of the use of arrows in signage to indicate direction. »

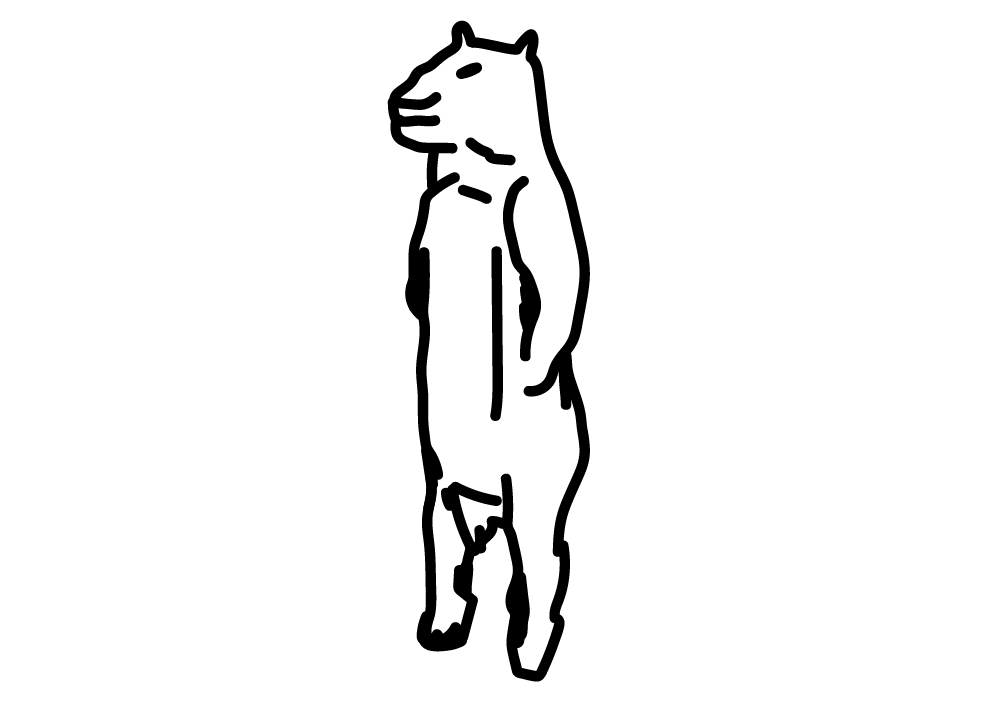

CHRISTY WAMPOLE

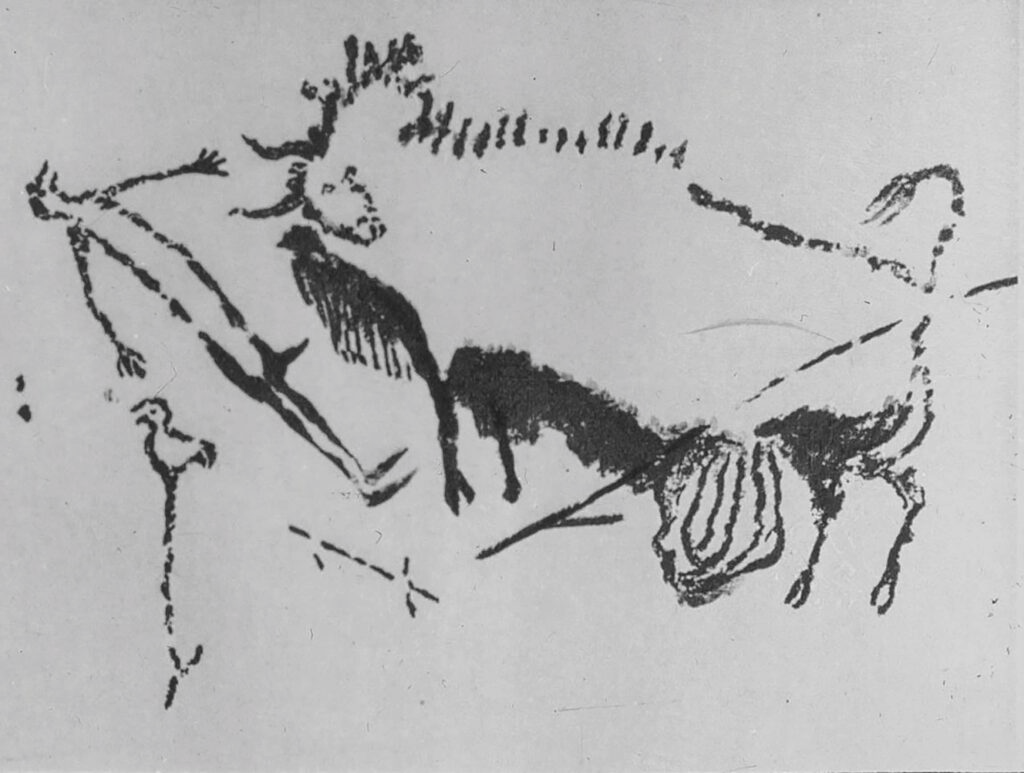

Rhinoceros and bird man

Rock painting of a rhinoceros. Catholic University of Leuven, Belgium.

Bird man; Lascaux, wounded man and bison. Catholic University of Leuven, Belgium.

The image that has generated the most speculation among scholars is probably the Bird Man of Lascaux, found in a deep part of the cave that came to be called le puits, meaning « the well » or « shaft. » His bird-like head, erection, and role in the scene — he is perhaps dead on the ground next to a staff with a bird on top and in between a rhinoceros and a disemboweled bison — have left anyone who has seen the image seeking an answer. Bataille called it a « prehistoric enigma » and spends a section called « The Various Explications of the Well Scene » rating the guesses other scholars had made about it since it was discovered. Holliday, too, wonders about it: « Who was this so-called Birdman? Was he a shaman or a mythical creature? Does this image tell a ‘true’ story — a hero or creation myth — or does it depict a shamanistic vision? » To this day, no one can seem to agree on what each of the components in the picture means or even whether they should be read as an ensemble.

Bataille, like Holliday, is happy to engage in speculation but is also quick to dismiss the speculations of others. He wrote a review of Georges-Henri Luquet’s L’Art primitif (1930), a book that argues that prehistoric cave paintings and children’s art bear many of the same features and should thus belong to a single category called primitive art. Luquet also argues that there are two main realist modes of figurative art, namely visual realism(which satisfies the adult eye’s expectations of what reality looks like) and intellectual realism (which conforms to the reality of the artist’s imagination). According to Luquet, primitive art privileges the second form of realism. Bataille takes issue with nearly all of his claims, emphasizing especially that the Aurignacian paintings often depict animals with impressive visual realism but depict only humans with what Luquet would characterize as an intellectual realist style. This fact more or less annuls Luquet’s clean dichotomy. Across multiple essays, Bataille crafts a theory about why Paleolithic paintings depict mostly animals, and do so in a realistic style, while treating humans only occasionally as a subject and in a less true-to-life way. According to Bataille, these drawings were a way to manifest the animal, to make it appear before the eye:

The animal had to be, in a sense, rendered present in the ritual, rendered present through a direct and very powerful appeal to the imagination, through the tangible representation. It was, on the contrary, useless to try to make man’s presence tangible. In fact, man was already present; he was there in the depths of the cave when the ritual was taking place.

The realistic renderings of animals were also a way, he argues, to honor the thing that humans felt themselves in the process of shedding, namely their own animality. In his piece « The Passage from Animal to Man and the Birth of Art, » he writes of the Lascaux painters, « These men made tangible for us the fact that they were becoming men, that the limitations of animality no longer confined them, but they made this tangible by leaving us images of the very animality from which they had escaped. »

Abbé Breuil may have hit the nail on the head in Beyond the Bounds of History (1949) when he suggested that the fascinating discoveries of prehistoric ingenuity set our imagination spinning in the vein of science fiction, but oriented toward the past and not the future, toward the black of the cave and not the black of space:

Not until less than one hundred years ago did Humanity come to possess solid proof of its unbelievable age, of the numberless generations through which its physical and ethical types were established; the silent stages during which Fire was first harnessed; then stone-chipping learnt; and then, much later, the art of sculpture and the engraving and painting of living beings. What a marvelous romance, surpassing in its reality all the imaginative dreams of Jules Verne and H.G. Wells!

This linking of prehistoric creativity and atomic anxiety, which prefigures by a few years Bataille’s same rhetorical move cited earlier, begins to feel like a wish for paths untaken, a call to imagine an alternate history for Homo sapiens that would involve more creation and less destruction. It is not surprising that Breuil and Bataille — both writing in postwar France, which was wedged between the US and the USSR, two nuclear empires — would project their atomic anxiety on the walls of prehistoric caves. One tries to escape the « gloom of present-day history » by dreaming about Paleolithic life, but this gloom works its way into the subconscious of these dreams. Interpretations of and conjecture about cave paintings might say more about the era in which the critic wrote than about the art itself.

Holliday closes the chapter on Cro-Magnon art with this ambivalent position:

I remain agnostic as to the function(s) of Paleolithic cave art, but I also wonder if we lose something when we try to analyze it too carefully. To paraphrase E.B. White and K.S. White: Paleolithic art can be dissected, as a frog can, but it dies in the process. The art is breathtakingly beautiful and, although it may be sacrilege for me as a biological anthropologist to say this, it gives us greater insight into the lives of the Cro-Magnons than the mere study of their skeletons ever can.

This is the paradox of viewing this extraordinary art in its own context. The call to speculate is there but so is the call to suspend all that rational reaching after. The images can also simply be beheld, not deciphered. Something in us knows that by solving the mystery, we risk making the pictures banal, just another cold case solved and filed away. The joy of speculation may come from the fact that we’ve found a truly unknowable object. The speculations might be less about acquiring knowledge and more about simply letting the brain try out a few things.

All in all, Holliday embraces both the speculative and the scientific spirit in Cro-Magnon: The Story of the Last Ice Age People of Europe, showing that certainty and uncertainty can be yoked together in service of creativity, the propulsive force that keeps us making, thinking, and wondering. When science interfaces with the humanities, when what is known and unknowable are forced to share space, when hard edges meet haze: that is where I would like to dwell permanently.

At the end of our tour in Font-de-Gaume, the guide invited questions about these beautiful forms before us. There in the half light, his answer to most of them was the same: « We simply don’t know. »

- Roland Barthes, « From Work to Text », in The Rustle of Language, trans. Richard Howard (New York: Hill and Wang, 1986). ↩︎

- Unless otherwise noted, the Bataille quotes are from various writings collected in The Cradle of Humanity: Prehistoric Art and Culture, ed. Stuart Kendall, trans. Michelle Kendall and Stuart Kendall (Zone Books, 2009). ↩︎

- In her article « Venus in Two Parts », Hartman outlines a method of archival research that involves « advancing a series of speculative arguments and exploiting the capacities of the subjunctive (a grammatical mood that expresses doubts, wishes, and possibilities) », « fashioning a narrative, which is based on archival research », « playing with and rearranging the basic elements of the story » and « re-presenting the sequence of events in divergent stories and from contested points of view. » ↩︎