On a logo and where it takes you.

There are many reasons not to use Europa and the bull as the logo of a magazine that calls itself The European Review of Books. If Greek mythology was thrown at you in school, you may dimly remember the story of Zeus, in the form of a majestic white bull, abducting Europa, a Phoenician princess. The figure might seem moldy, already co-opted a thousand times before. A statue of Europa and the bull stands in frozen gallop in front of the European Council’s headquarters in Brussels. Strasbourg has one, too, greeting the European Parliament building’s passersby. Europa is on the damn currency. If the 2-euro coin in your pocket is the Greek varietal, it likely sports a Europa with bull, copied from a Spartan mosaic, third century AD.

And yet it didn’t even cross the editors’ minds to use or not use Europa until, one day in an online meeting with a designer in Oslo, the figure of a woman riding a bull, side-saddle, appeared on a shared computer screen. We liked it. A logo might start as a designer’s whim. Only then does one look for meanings to fill it with. Hence this circuitous search for Europas: from the mythic to the artistic, the fictional to the political, the psychological to the satirical, and finally to the unfinished.

I.

The story is ancient. Tauromorphous Zeus steals Europa away to sea, landing eventually on the island of Crete, where she will bear him three sons. Her dutiful brothers set out to find her: Cilix to Asia, Phoenix to Asia Minor. Cadmus, in the course of his failed search, will wander, slay dragons and found Thebes.

The historian Michael Wintle’s compendium of Europa iconography notes that the original myth registered antique rivalries: Greece versus Troy, Greeks versus Persians. Some broader distinction between « Europe » and « Asia » would emerge over time. Herodotus, writing in the 5th century BC, was « not impressed » by the legend, as Norman Davies notes in the opening of his own grand history of Europe (1996): « the abduction of Europa was just an incident in age-old wars over woman-stealing. » So it goes. Roman poets were impressed by it, though, and eagerly embroidered the Hellenic myth. Horace’s Odes gave ravished Europa the consolation prize of naming a continent: « Away with sobbing, » says Jove, revealing himself; « be resign’d / To greatness: you shall give your name / To half mankind. » (The original Latin refers to a « section of the world »; the old John Conington translation, from 1882, upped the European portion to half mankind.) Ovid’s Metamorphoses laced in erotic detail. Europa, quieting her « virgin fears, » brings flowers to the bull, « tempting, to his gentle mouth », whereupon « the loving god in his great joy / kissed her sweet hands, and could not wait her will. » (This is Brookes More’s translation, from 1922).

The bull bears her out to sea,

while she affrighted gazed upon the shore —

so fast receding. And she held his horn

with her right hand, and, steadied by the left,

held on his ample back — and in the breeze

her waving garments fluttered as they went.

Uncomfortable evocation of mythic sexual violence? Check. Susan Brownmiller’s classic study of rape, Against Our Will (1975), notes that such myths « reveal very little » about rape itself. The gods « raped with zest, trickery and frequency, » to be sure, yet « the goddesses and mortal women who were victim to these rapes, Hera, Io, Europa, Cassandra, Leda, rarely suffered serious consequences beyond getting pregnant and bearing a child, which served to move the story line forward. » The story line, in this case, is a myth of origin via the abduction of an outsider. As the literature scholar Rita Barnard has noted of such myths and their national function, « rape has traditionally served as a figure for examining new, exogamous national beginnings. » Helen of Troy hatched from an egg laid by Leda, an Aetolian princess, raped by Zeus in swan form. The rape of the Sabine women is another such story, lending a mythic gloss to early Rome’s incorporations of neighboring populations.

And the bull? Cults of the bull were everywhere in antiquity and reach back to prehistory, well beyond what’s now called Europe. Zeus and Europa are a relatively late entry in the corpus, along with the Minotaur — child of Pasiphaë and Poseidon, the latter in bull form. (The Minotaur is Europa’s step-great-grandson, as Michael Rice notes in his study of bull cults, because Pasiphaë will marry Europa’s grandson, Minos II.) If there is a collective unconscious, « European » or otherwise, mythic bulls are roaming its freaky pastures.

II.

Browsing the enormous art-historical corpus of Europas, one finds expressions of shock, fear, despair, rage, desire, boredom. She might look with mild disdain on the land being left behind. Veronese (1572) has the bull licking Europa’s left foot. Rembrandt (1632) and Goya (1772) will place the viewer on the shore with Europa’s frantic maids, as the bull plunges away into the sea. Titian (1560-1562) puts us in the water with woman, beast, and a peeping cupid.

Titian, The Rape of Europa, ca. 1560–1562

« Europa bitterly

hears the crashing

foam… » Osip

Mandelstam,

inspired by Valentin

Serov’s Europa

Osip Mandelstam, inspired by a painting by Valentin Serov

С розовой пеной усталости у мягких губ

Яростно волны зеленые роет бык,

фыркает, гребли не любит – женолюб,

Ноша хребту непривычна, и труд велик.

Изредка выскочит дельфина колесо,

Да повстречается морской колючий еж,

Нежные руки Европы – берите всё,

Где ты для выи желанней ярмо найдешь.

Горько внимает Европа могучий плеск,

Тучное море кругом закипает в ключ,

Видно, страшит ее вод маслянистых блеск,

И соскользуть бы хотелось с шершавых круч.

О, сколько раз ей милее уключин скрип,

Лоном широкая палуба, гурт овец,

И за высокой кормою мельканье рыб –

С нею безвесельный дальше плывет гребец!

(1922)

Pink foam of exhaustion about his soft lips,

the bull digs fiercely into the green waves,

snorts, doesn’t like to row, women he likes,

his spine unused to the burden, the labour great.

Now and then leaps from the water a dolphin wheel,

swims past a prickly hedgehog of the sea,

tender hands of Europa, take it all,

where you can find a fitter yoke for the beast.

Europa bitterly hears the crashing foam,

the cloudy sea all round is a boiling spring,

you can see she fears the water’s oily gleam,

how she longs to slip down from the shaggy cliffs!

O how much sweeter would be the rowlocks’ creak,

flicker of fish beyond the lofty stern,

deck stretched wide like a lap, a flock of sheep –

the rower plows on with her, without an oar!

(translated by Peter France)

This poem was added to the essay 17 July 2022. We are grateful to Peter France for his translation.

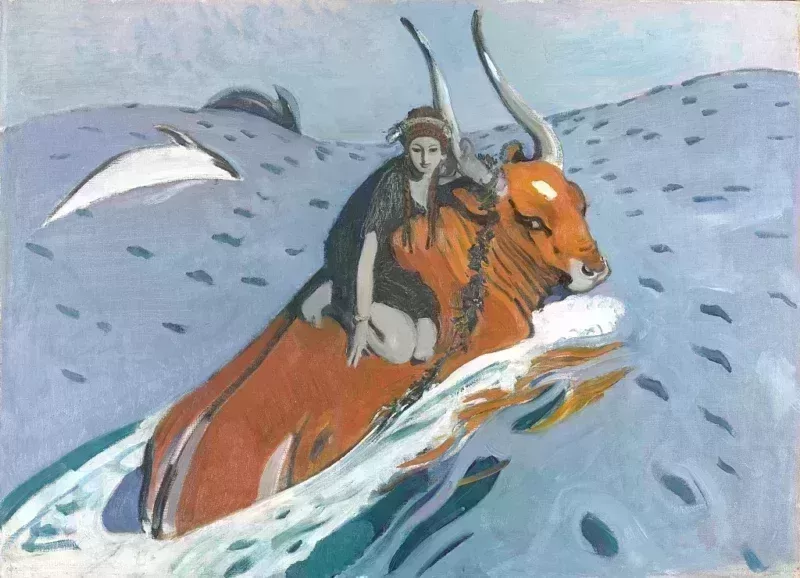

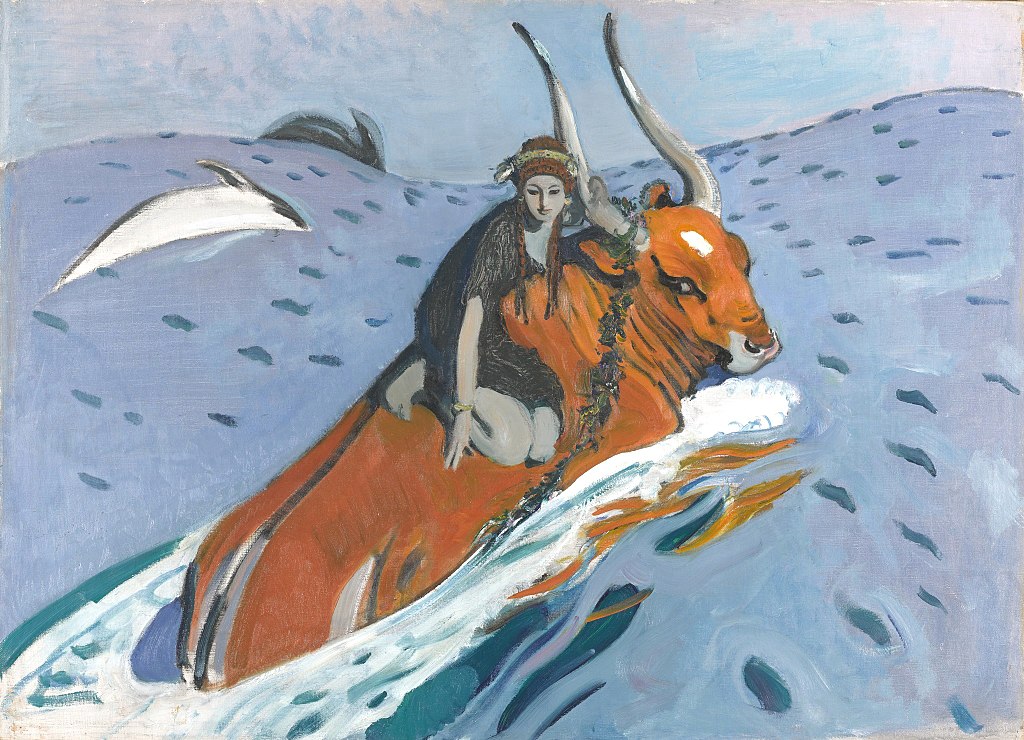

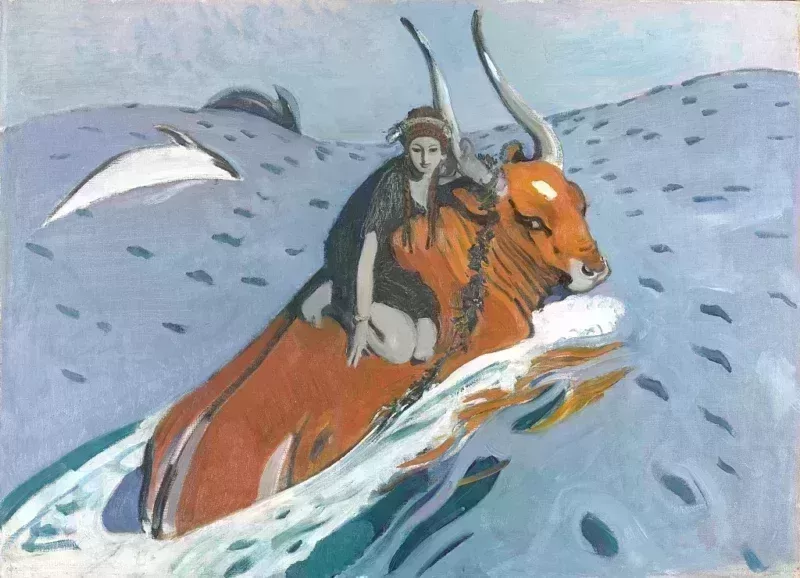

Any invocation inevitably summons that vast repertoire, claiming it or disclaiming it. The legend remains up for grabs, in and beyond Europe. Jump ahead a few centuries to the Russian artist Walentin Alexandrowitsch Serow’s Похищение Европы (Rape of Europa, 1910): Europa and bull (orange now, not white) look back at us as they reach the blue crest of a wave, with dolphins instead of cupids. Have we lost Europa or are we lost with her?

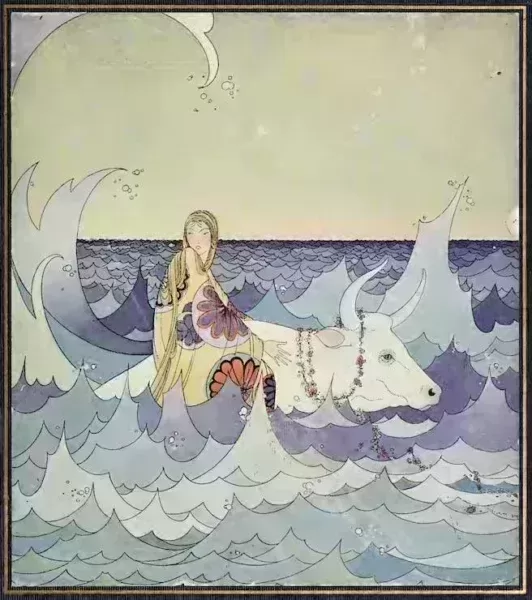

Nathaniel Hawthorne rewrote Greek myths for American children in Tanglewood Tales (1853), making the abduction of Europa rather chaste and mournful. In a beautifully illustrated version by the American artist Virginia Frances Sterrett (1921), Europa is draped in art-deco and modern ennui.

Walentin Alexandrowitsch Serow, Похищение Европы, 1910; Virginia Frances Sterrett, cover illustration for Nathaniel Hawthorne, Tanglewood Tales (1920).

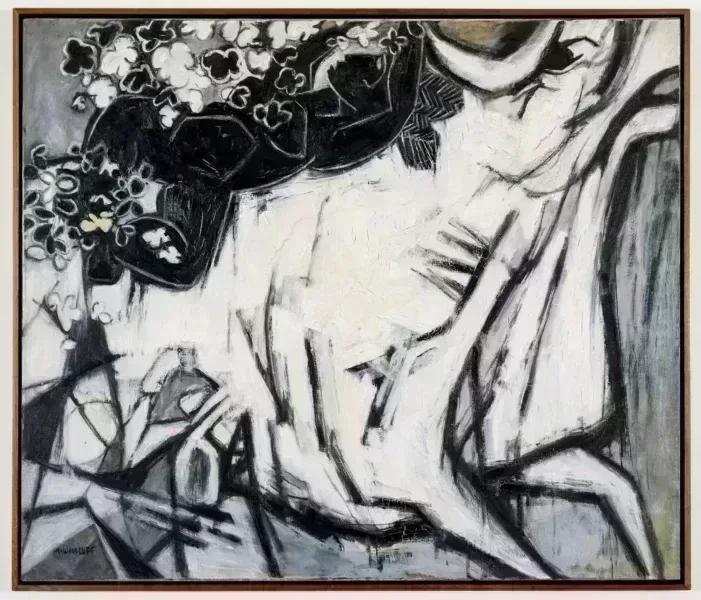

In Africa and the Bull (1958), by the black American artist Hale Woodruff, the reclining figure of Africa echoes and inverts Henri Matisse’s L’Enlèvement d’Europe (1929), which Woodruff may have encountered during his years in Paris in the 1930s. (Woodruff painted a Europa around the same time, but titled it, intriguingly, « Return of Europa ».)

Hale Woodruff, Africa and the Bull, 1958, Oil on canvas, 44 1/4 x 52 3/4 in. Source: The Studio Museum in Harlem

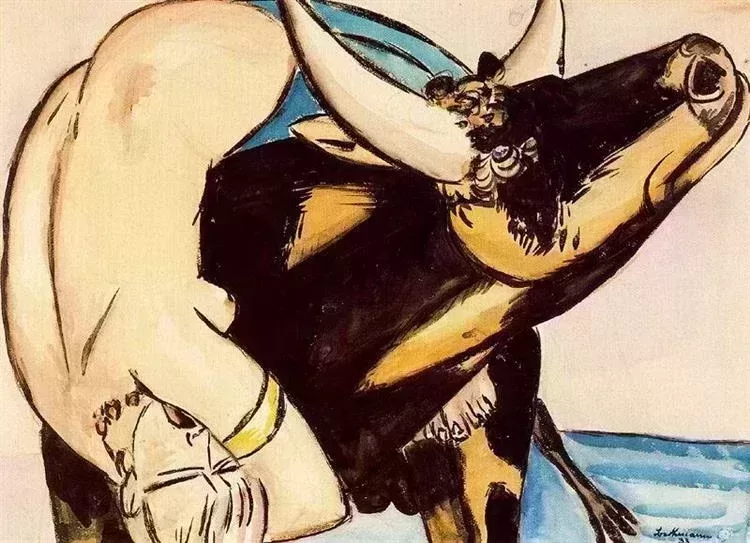

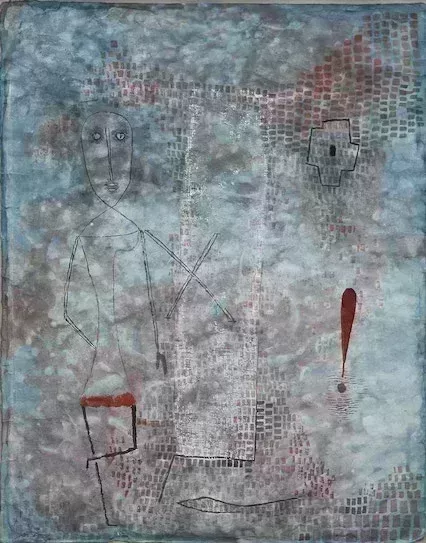

It has been conventional to read into the myth some European spirit: as if Europa’s adventure projects restlessness, motion, innovation, curiosity, enterprise, and so on. Implosions of such triumphant clichés can then resonate all the more powerfully. In Max Beckmann’s The Rape of Europa (1933), Europa is unconscious, and the bull is the color of a brownshirt. Beckmann would be condemned by the Nazis as a « degenerate artist » in 1937. For abstraction with punctuation, one could do worse than Paul Klee, Beckmann’s fellow degenerate. If you squint at his Europa (1933), you might discern the shape of bull in its tiles, but it’s the exclamation point that shouts at you.

Max Beckmann, The Rape of Europa (1933); via Wikimedia Commons.

Paul Klee, Europa (1933); Kunsthalle Bielefeld; public domain.

The Nazis’ own Europas were many. The fortnightly Nazi magazine Signal even took Europa & bull for its logo — a journalistic nugget that raised our editorial eyebrows. A propaganda tool of the Wehrmacht, Signal was modeled on Life magazine and distributed in twenty-some languages through occupied Europe.

After the war, as Wintle notes, Europa was again an available allegory for use in satire or lamentation. The German painter Emil Scheibe figured Europa as a prostitute in Europa und ihr Stier (1952); the bull is butchered outside her window. In a dig at the postwar Marshall Plan, published in Die Zeit, the cartoonist Mirko Szewczuk has a naked Europa straddle not a bull but a can of American corned beef.

III.

Europa need not be a personification of the continent of Europe; that association only became commonplace in the Renaissance. Europa emerges over the centuries as a queen, sitting astride a now-subordinate bull. The Albert Memorial in London (1872), for instance — that « vast cathedral to Victorian self-worship and arrogance », in Wintle’s phrase — seats queen Europa on a steer, flanked by personifications of France, Italy, Britannia and Germany. An Aryanized « Europe » is thus drawn from a non-white Other, simultaneously subsuming and excluding it, in the manner that only myths can. Is such imperiousness intrinsic, somehow, to the original tale? For the Byzantinist Hélène Ahrweiler (2000), « the abduction of women signals, principally, expansionist wars; and I would go so far as to say that it also defines a colonialist policy. »

Many Euro-visionaries in the twentieth century would fix on Cadmus, Europa’s bereft brother, who is told by the oracle of Delphi to give up his search and follow a particular cow until it falls from exhaustion, and there to establish a city. For Denis de Rougement, the story of Cadmus acknowledged a fundamental loss — Cadmus never finds his sister, after all — but then spurs modern Europeans toward a higher adventure: « It is the search for Europe which has created her, » he wrote, cajoling readers toward European unity in 1963. « To seek Europe is to make her! Her existence is in the search for her. » Zygmunt Bauman, in Europe: An Unfinished Adventure (2004), finds similar inspiration in Cadmus: « Europe is not something you discover; Europe is a mission — something to be made, created, built. » Powerful ironies abound in this. Cadmus’s founding of Thebes is the paradigmatic instance of autochthony, after all: he plants the teeth of a slayed dragon in the ground, and from the literal soil there springs a race of Spartoi. A ready fantasy for nationalisms of various kinds, yet Cadmus, the founder, is necessarily from elsewhere. Europa, too.

(Carl Jung, for what it’s worth, believed that « the psychological meaning of the [Cadmus] myth is clear », as he wrote in his last major work, Mysterium Coniunctionis: An Inquiry into the Separation and Synthesis of Psychic Opposites in Alchemy [1970]: « Cadmus has lost his sister-anima because she has flown with the supreme deity into the realm of the suprahuman and the subhuman, the unconscious. At the divine command he is not to regress to the incest situation, and for this reason he is promised a wife. » The cow that leads Cadmus to the site of Thebes is the sister-anima again, « acting as a psychopomp » toward his real destiny as dragon slayer. Cadmus slays a dragon and wins a wife, « Harmonia, who is the dragon’s sister. » The dragon, Jung wrote, « is obviously ‘disharmony’. » Roger that. Jung, 81 at the time, could still fire off an « obviously » to hilarious effect.)

Stuart Hall, writing in 2002, was skeptical of attempts to refashion Europa as an allegory for a bright new Europe, freshly emerged from the Cold War, calling itself « moderate, liberal, democratic, tolerant, free-market, constitutional ». The legend of Europa, Hall thought, was « almost too predictable and over-determined »; it needed deconstruction before it could be reconstructed. Hall looked to other European mythologies that might better evoke the Others, internal and external, against which Europe has long been defined, from the wandering Jew, « that epitome of the internal Other », to the marvels and imaginary monsters on the margins. The « hybrids, hermaphrodites and anthropophagi of the classical periphery », or the « wild men » and « wild women » of medieval Europe, « with their matted hair and naked, hirsute bodies », who « mapped out Europe’s liminal edge, » haunted its « woods and wildernesses », marked « the ever-shifting boundaries between Europe’s inside and outside » — why not figure the new Europe with one of them?

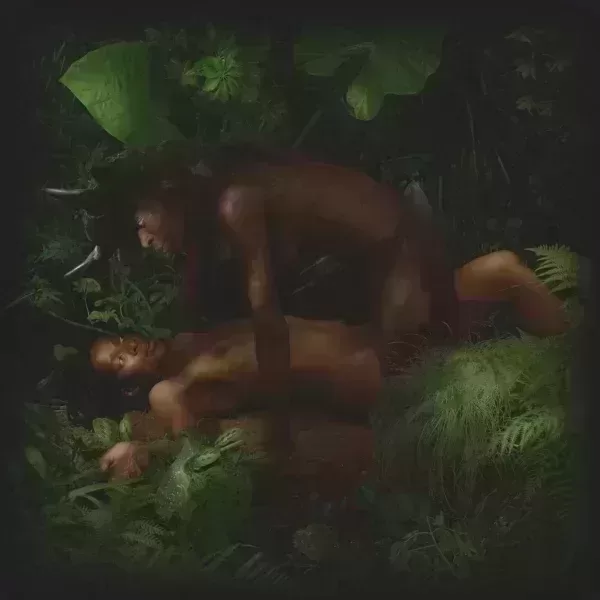

It is bracing, in this light, to encounter the South African artist Nandipha Mntambo’s The Rape of Europa (2009), a digitally enhanced photograph in which Mntambo herself plays both Europa, naked and recumbent, and bull, with horns and wild fur. The composition references Picasso’s Minotaur Kneeling Over Sleeping Girl (1933), though this Europa is not sleeping. On one level, Mntambo’s reimagined Europa answers Hall’s challenge, figuring both Europa and bull as black women and layering European traditions with inversions and counter-traditions. But it’s an avenue to something more fundamental, too: the binary of Europe and non-Europe is less interesting than the porous binary between human and animal.

Nandipha Mntambo, The Rape of Europa, 2009. Archival pigment ink on cotton rag paper, 112 x 112 cm. Photographic composite: Tony Meintjes © Nandipha Mntambo. Courtesy of Stevenson, Amsterdam / Cape Town / Johannesburg

In Mntambo’s Europa (2008), from the same series, Europa herself is horned, and fixes an arresting gaze on the viewer. Stare at it awhile and you’ll find yourself contemplating primordial hybrids and posthuman futures, kinships new and strange. It feels less like a revision than a new foundation.

Nandipha Mntambo, Europa, 2008. Archival pigment ink on cotton rag paper, 112 x 112 cm. Photographic composite: Tony Meintjes © Nandipha Mntambo. Courtesy of Stevenson, Amsterdam / Cape Town / Johannesburg

Hall wondered whether any myth would be appropriate for the modernity, the disruption, the precarity and marginality that had been unleashed by European empire and contemporary « turbo-capitalism ». A recent re-writing by the Latvian writer Nora Ikstena in the anthology Europa28: Writing by Women on the Future of Europe (2020) redirects the legend of Europa toward this end. Europa is now a rebellious princess, whose father is « coercive and authoritarian ». In a twist, the castle is not in far-off Phoenicia but in a bubble of European privilege. The father even invokes the anthem of the European Union: « Look, » he says, presenting Europa to a suitor she will not love, « here is my ode to joy. » This Europa will not give her name to Europe; she’d rather take it back.

The bull appears to Europa first in a dream, majestic but wounded: « One of his front legs was badly injured and streaming blood, which the bull was licking … so large and so helpless in his pain. » She comes to his aid with a bandage torn from her linen dress. Soon the bull appears in waking life: « He came right up to Europa, leaned his large head against the balcony railing and gazed at her with submissive, inviting eyes, which seemed to say, ‘Come, let’s flee from this place.’ » What follows is Europa’s « staggering voyage through reality, so beautiful and yet so heart-rending at once. » This is not an abduction but an emancipation, not a founding but an awakening. The world beyond the wall is already populated, already unequal, and already corrupt.

People chained together, very much like the circle of stars in the sky, were all living their own lives. They spoke different languages in both a literal and figurative sense. Poor huts alternated with magnificent castles. The foremost thieves were given honorable positions while petty crooks were thrown in jail. Ministers and priests confessed horrifying sins.

Europa encounters nationalist mobs (« They demanded self-determination, they fought for their rights to sing their own songs, to eat their own bread and drink their own water… »), refugees (« vast seas full of overcrowded boats, where people who looked different and were clearly in despair fought for survival, hoping to make it to shore »), and refuges of culture, too. « As they journeyed further, they also saw hideaways where people gathered to read books, listen to music, and admire paintings. But these refuges, and those who populated them, were far too few. » Zeus is never named.

Does anything in this sprawling catalog of rewritten myth redeem the figure of Europa, for our purposes? Will these contradictory lineages be summoned, however dimly, in our readers’ minds? Stuart Hall acknowledged that the myth could be read in emancipatory or pluralistic ways, but was anyone really doing it? « The figure is certainly not being used, » he concluded, « to remind contemporaries that much of what we now think of as Europe’s achievements were originally external to Europe and had non-European, Asian, African and Islamic roots. » Yet Hall’s critique might be canonical now, at least in universities and in progressive circles. Kalypso Nicolaïdis’s Exodus, Reckoning, Sacrifice: Three Meanings of Brexit (2019) winks at « Zeus’s truly inspired move, in appropriating a foreign woman hailing far from the slopes of Olympus who will one day come to represent us Europeans. » Cretan rather than Christian, « This Europa calls for the recognition that we are made of others. » In Citizens of Nowhere: How Europe Can Be Saved from Itself (2018), Lorenzo Marsili and Niccolo Milanese can invoke a postcolonial, postnational Europa as a matter of course:

At a time when many would like to define Europe along ethnic or national lines, and at a time when the proliferation of border fences goes hand in hand with the identification of an indigenous ‘people’, the story of Europa serves to remind us that from the beginning ‘Europe’ has been thought of as bigger than it is now typically understood as being, and that it exists at the crossroads of multiple paths. Europe, ultimately, is nowhere.

IV.

Europa has taken us far afield from our original purpose, which was to explain a designer’s line drawing. What’s in a logo, after all? These lineages are incidental and hopefully not a burden. Maybe the logo can carry the spirit of founding something, including accidental foundings along the way. So we can round out this ramble with unfinished things: a landscape and a sketch. The landscape is J.M.W. Turner’s. We might say he read Europa twice.

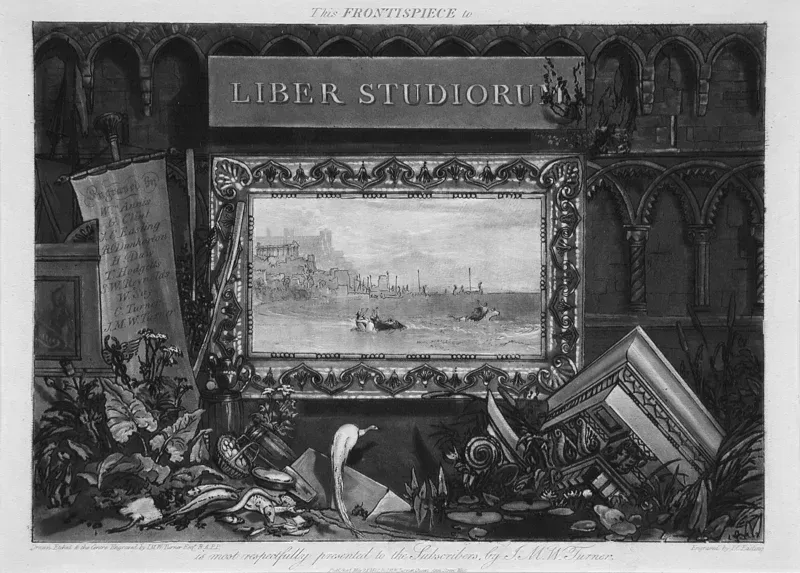

J.M.W. Turner, Liber Studiorum, 1807.

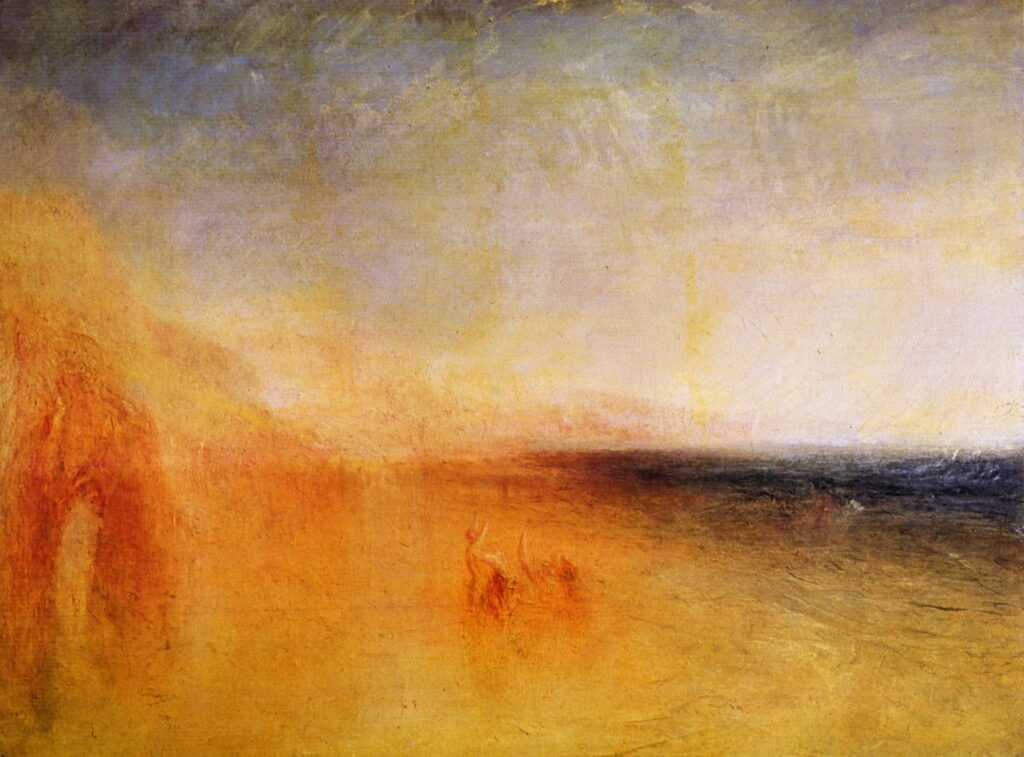

Europa was the frontispiece of his Liber Studiorum, a book of etchings begun in 1807, in which gothic ruins and still-life detritus surround a framed landscape of the bull carrying Europa away. The shore is itself scattered with ruins. Later in life, Turner returned to the composition and worked on a landscape without the decorative trappings, without the artificial ruins. One has to look at the canvas for a good while before actually seeing the bull and Europa: a speck of white and a daub of brown peeking out from the blue wedge of water. The unfinished landscape is itself a drama of interpretation — misty and obscure, but alive with color.

J.M.W. Turner, Europa and the Bull (c.1840s); Taft Museum of Art, via http://www.zeno.org – Contumax GmbH & Co. KG

The sketch is Albrecht Dürer’s, doodled in Venice in the 1490s. He had fled an outbreak of plague in Nuremberg. Europa’s maids clamor on the shore in the exotic scene, but other creatures and commotion crowd them out: cherubim in the water, recreational dolphin-riding, two satyrs picking fruit (Adam and Eve?). Europa, with studied expression, pays them little mind. In Turner’s landscape, Europa and bull will recede into abstraction; in Dürer’s sketch, they burst from the page.

Albrecht Dürer, Studienblatt mit dem Raub der Europa (1495); Albertina Museum; via http://www.zeno.org – Contumax GmbH & Co. KG.

The drawings on the page’s right side — headshots of a melancholy Venetian lion, a pot bubbling with what might be gold — may or may not have anything to do with Europa’s adventure. An Apollo holds his bow; the arrow might as well be a paintbrush or a pencil. A turbaned old man (the alchemist? a philosopher? St. Jerome in oriental garb?) contemplates a skull as if it holds more wisdom than the book that lies at his feet. Let’s hope he’s wrong.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Hélène Ahrweiler, The Making of Europe: Lectures and Studies (Athens: Livanis, 2000)

Rita Barnard, « Rewriting the Nation », in The Cambridge History of South African Literature, ed. David Attwell and Derek Attridge (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012), 652–75

Zygmunt Bauman, Europe: An Unfinished Adventure (Cambridge: Polity, 2004)

Susan Brownmiller, Against Our Will: Men, Women, and Rape (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1975)

Norman Davies, Europe: A History (New York: Oxford University Press, 1996)

Denis de Rougemont, The Meaning of Europe (London: Sidgwick and Jackson, 1963)

Stuart Hall, « ‘In but not of Europe’: Europe and its myths », in Figures d’Europe / Images and myths of Europe, ed. Luisa Passerini (Brussels: Peter Lang, 2003)

Nathaniel Hawthorne, Tanglewood Tales, illustrated by Virginia Frances Sterrett (Philadelphia: The Penn Publishing Company, 1921)

Nora Ikstena, « The Bull’s Bride », in Europa28: Writing by Women on the Future of Europe, ed. Sophie Hughes and Sarah Cleave (London: Comma Press, 2020)

C. G. Jung, The Collected Works of C. G. Jung: Mysterium Coniunctionis (Volume 14): An Inquiry into the Separation and Synthesis of Psychic Opposites in Alchemy (London: Routledge, 2014)

Lorenzo Marsili and Niccolò Milanese, Citizens of Nowhere: How Europe Can Be Saved from Itself (London: ZED Books, 2018)

Tamera Lenz Muente, « J. M. W. Turner’s Europa and the Bull », Frame|Work(The Taft Museum of Art) (blog), December 14, 2018, https://www.taftmuseum.org/blog/posts/2018/december/j-m-w-turner-s-europa-and-the-bull-telling-a-story-with-light-and-atmosphere

Kalypso Nicolaïdis, Exodus, Reckoning, Sacrifice: Three Meanings of Brexit (London: Unbound, 2019)

« Notes on #MeToo, COVID, and Rape of Europa. Part II », Standing Ovation, Seated (blog), April 29, 2020, https://artrussia.org/2020/04/29/notes-on-metoo-covid-and-rape-of-europa-part-ii/

Michael Rice, The Power of the Bull (London: Routledge, 1998)

Michael J. Wintle, The Image of Europe: Visualizing Europe in Cartography and Iconography throughout the Ages (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009)