published in Issue Three

(2022)

I watched the movie three times, in three theaters, at three different distances from the screen. The first viewing, at FSK-Kino near Oranienplatz in Berlin, cost €9 and took place in a packed theater. Sitting in the front row — no other seats were left — the picture was overwhelming and could only be taken in pieces. At that neck-twisting angle, the film’s proportions were too formidable, its figures too looming. I was made small by them. A second viewing, at Delphi Lux Kino near Bahnhof Zoo, which cost €12 and allowed me to sit in the middle row of a small, mostly empty theater, proved the most human-scale distance at which to watch. Only the picture was in view, and it was just the right size. The characters felt the same size as me. The final viewing at ACUD Kino, around the corner from Rosenthaler Platz, cost me €8. As part of what I realized had become an experiment — to watch a film from three different angles and see what knowledge these different viewings could produce — I sat in the last row. This choice brought with it distractions: cellphone screens, whispering silhouettes who consumed beverages and dropped things. These people, as visual noise, became a part of the film. Their optical commotion competed with the film’s action and made me feel far away, a detached observer who was denied the chance of a pleasant immersion.

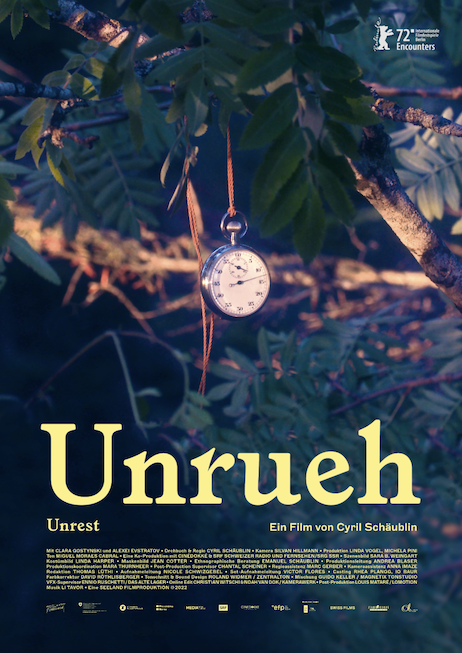

The movie was Cyril Schäublin’s Unrueh (2022). It is ostensibly about the outsize influence that a group of clockmakers in a small Swiss village had on the burgeoning anarchism of a real historical figure, the Russian radical Pyotr Kropotkin (1842-1921). His anarcho-communist activities were grounds for a forty-one-year exile starting in 1874, which gave him the chance to study firsthand how the Swiss, French, and English anarchists organized life and action. On its surface, the movie is about modernity, time, power, technology, money, memory, and capital (those who have it and those who generate but do not possess it). The movie is about all of those things, but as I tried it out at different scales and for different prices in theaters spread across the map of Berlin, I confirmed the early intuition I’d had about its secret theme...

Uli Edel’s German cult film Christiane F. (1981), about a teenage heroin addict, based on Kai Hermann and Horst Rieck’s book Wir Kinder vom Bahnhof Zoo, was filmed right around the corner.

Schäublin took a great deal of inspiration from Florian Eitel’s impressive book Anarchistische Uhrmacher in der Schweiz [Anarchist Clockmakers in Switzerland] (Bielefeld: transcript Verlag, 2018), a microhistory that tells the story of how a small-scale municipal organization effort had global implications for a burgeoning international anarchist movement.

Because precision, of maps or of timepieces, is so central to the plot, my mind drifted several times to the Borges’ story « Del rigor en la ciencia » (On Exactitude in Science, 1946), about an imaginary empire whose mapmakers have made their representations so precise, only a 1:1 scale map (the exact size of the territory it depicts) is satisfactory to them.

Schäublin’s first feature film, Dene wos guet geit (Those who are fine), from 2017, was also shot by Silvan Hillmann and uses a similar compositional style. Set in the present, it treats another aspect of capitalism. The protagonist, who works for a large health insurance corporation, scams elderly women and steals their wealth.

One of the first real motion pictures was the 1895 black-and-white short Workers Leaving the Lumière Factory in Lyon. Louis Lumière’s iconic scene was perhaps on Fritz Lang’s mind as he filmed the « Shift Change » scene in Metropolis (1927), in which one squad of workers emerges from the factory’s prison bars while another squad enters. Lumière’s film is also clearly cited by Charlie Chaplin’s Modern Times (1936), which in its first scene montages herded sheep and workers headed from the subway toward factory drudgery.

In one of the film’s many meta-referential moments, as they are asked to act in a worker-organized theater play about the Commune, the protagonists Kropotkin and Joséphine say, « Je ne suis pas protagonist » (« I am not a protagonist »).

I will never forget the French writer Michel Tournier’s observation in one of his books that poor people’s trash is heavy — full of bones, potato peels, gristle, corn cobs, apple cores — while rich people’s trash is light — full of gauzy cellophane, wrapping paper, disposable plastic containers, styrofoam peanuts. He wrote this in the mid-twentieth century. By this measure, are most of us rich today?

They sing the French version of « Rufst du, mein Vaterland », whose melody many will recognize as that of « God Save the King » or « My Country ’Tis of Thee. »

« French toys always mean something, and this something is always entirely socialized, constituted by the myths or the techniques of modern adult life: the Army, Broadcasting, the Post Office, Medicine (miniature instrument-cases, operating theatres for dolls), School, Hair-Styling (driers for permanent-waving), the Air Force (parachutists), Transport (trains, Citroëns, Vedettes, Vespas, petrol-stations), Science (Martian toys). » Roland Barthes, Mythologies, trans. Annette Lavers (New York: Hill and Wang, 1972), 53.

For more on this iconography, see Michael Marder, Pyropolitics in the World Ablaze (London: Rowan and Littlefield, 2020).

Gerhard Richter’s blurred paintings of photographs are one of the more conscious attempts to play with these visual metaphors of sharpness and blur.