Read in:

« I guess it all began, » he said, « because of that weak-headedness my father sometimes had. It just rubbed me the wrong way. »

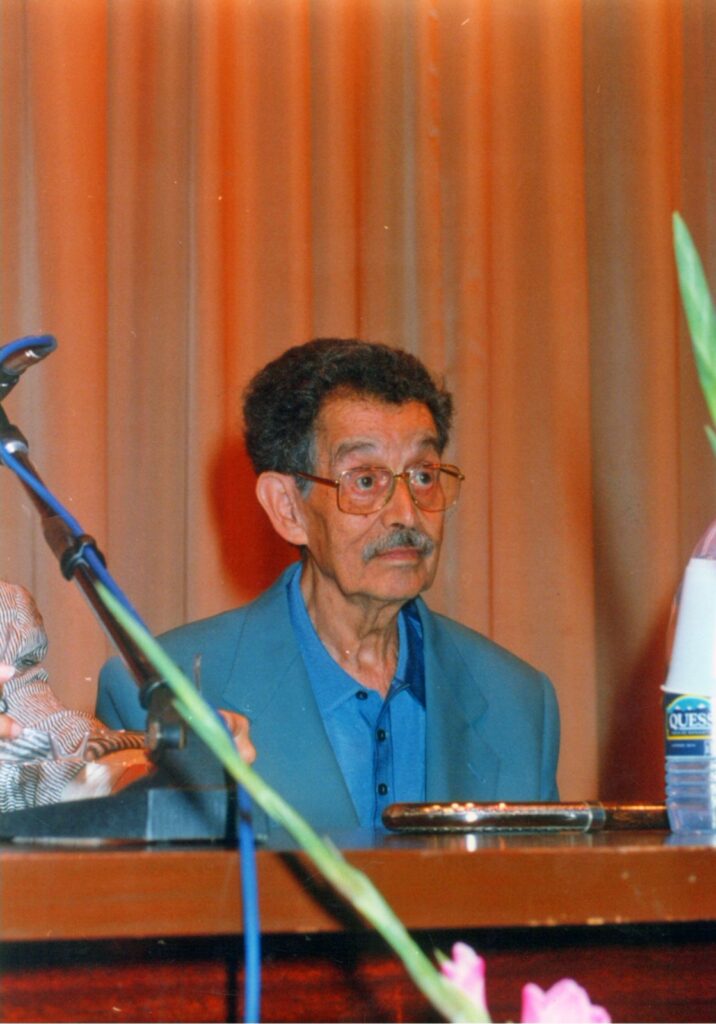

Enric Valor with his wife Mercè

Who was Enric Valor?

Enric Valor

Enric Valor (1911-2000) is one of the most important Valencian authors of the 20th century. He is primarily known as a novelist and grammarian. At a time when the Catalan language (of which Valencian is a regional variant) was under threat from the cultural bulldozer of the Franco regime, which condemned the use of anything but Castilian Spanish in public communication, he went to great lengths to disseminate knowledge of the language through writing grammars and linguistic studies (as well as teaching it to fellow inmates when he was imprisoned by the regime for his cultural activities).

Apart from his extensive labors as defender and disseminator of Valencian, he is the author of five significant novels, including The Cassana Cycle, a trilogy depicting the life and landscape of his times and homeland (Castalla, in Alicante). He also wrote 36 Rondalles Valencianes (Valencian Folktales), which he collected from locals in towns and villages of Alicante and modified into elegant literary versions set in the specific locations and landscapes of his homeland.

A translated selection of these tales is forthcoming with Routledge under the title Valencian Folktales, introducing his stories to an English-speaking audience for the first time. The book is edited by Valor’s granddaughter, linguist Maria-Lluïsa Gea-Valor, together with Paul Scott Derrick, and includes a study of Valor and his work. In the collection’s introduction, she writes about her grandfather, who grew up in a rich and culturally refined family in the countryside: Landowners who went bankrupt and then became part of the struggle of the working class in the city they had to move to. Valor soon turned to political and cultural activism, like many other Catalans in the time of the Republic and under the threat of Franco’s fascism. In the civil war Valor fought on the losing side of the Republicans, and was witness to the war’s horrors.

In 1936, the train that sent the only copy of the manuscript of Valor’s first novel (El misteri del Canadian or The mystery of the Canadian) to his publishing house in Barcelona was bombarded, and the manuscript was never recovered. The regime made victims of books, too. Luckily we have his later work.

The old fellow sat there, calm and resigned. His beady blue eyes shone with a glow of melancholy glee. The doctor had told him that I could be trusted and that he could tell me everything. He talked as though we had been lifelong friends.

We were seated in front of the lovely asylum, surrounded by groves of lemon trees and palms. Not far away, the sea murmured gently over the pebbles on the beach. It was a bright, sunny day in March; the sweet-smelling air was still. What that old man told me was a strange, fantastic and subjective reality.

« I guess it all began, » he said, « because of that weak-headedness my father sometimes had. It just rubbed me the wrong way. »

« Not much of a sin, is it? »

« Well, everything started with that sin. What happened? Why did that one small defect, so natural for someone in his seventies, irritate and disgust me instead of making me feel sympathy and love? I think it must have been the Devil’s work. That’s right. No, don’t laugh. The Devil’s work. Do you really believe he isn’t just as real as you and I? And that he doesn’t roam through the mountains, where there are souls to tempt like everywhere else?

« I used to take my animals out to pasture on the farm I had up on the Onil range. And whenever I’d try to see if my neighbor’s goats were gnawing on a pine tree, or if my wife was spending too much money, or if my boy wasn’t doing as I said, who’s to say that ‘he’ wasn’t lurking in the vicinity? Sometimes, when there wasn’t a hint of wind, I could clearly see the branches of a pine tree moving. Now wouldn’t that be the Enemy rubbing against them?

« One day, when my father was sitting out in the sun by the front door, he asked me some silly question: was it Wednesday, or was I going to put the goats in the corral; and I blew my top!… I raised my hand and I slapped his thin, bony cheek. Yes sir. That I did. Don’t you just know the Evil One was jumping for joy somewhere nearby, while my heart was pounding with senseless rage? It was my selfishness, my ugly temper. Did it bother me that my father was getting on, or did I maybe resent the food I gave him? I looked at my dad and saw a mark where I had hit him. A few big tears ran down his cheeks. But my heart was hard.

« I yelled in his ear, ‘I don’t want any nut cases in this household!’

« It all upset my wife. She was fond of her father-in-law; so she helped me take him to my brother’s place, over in the town of Ibi. It took us five long hours to get there.

« Well, the years went by and my poor old father died without ever seeing me again. Somewhere in his mixed-up mind he was afraid of me. Whenever he heard my name, he looked at the door and started to tremble. At least, that’s what they told me.

« Then, when I grew older, I began to be afraid that the Lord would punish me. Maybe, I often thought, I’ll get senile myself, and it won’t be long in coming. But not a chance. Just look!… What do you think about this? In this place where I am now, I have to put up with a heap of folks that are a lot crazier than my poor old father ever was.

« This is how it came about.

« I was sixty years old. That was ten years ago. I was out walking in the fields around my farmhouse one morning. My goats were nibbling the rosemary and the thyme that were then in bloom. I was strolling through the pinewood up toward the Visatabella spring, above Fontalbres, high up, close to the clouds, when the whole herd lifted their ears and the billy goats puffed out their cheeks. The way they were jumping all about I didn’t know if they had seen a big snake or a wolf—there are some in the Patirás pine forest—or what they might have scented.

« ‘Hey there! Hey goats!’ I shouted, spreading out my arms.

« But they didn’t want to move. The nanny goats sniffed the ground and jumped up and strained backwards, and of course they pulled the rest of the herd. And all of those animals crowded around me… Ha, ha! There I was, surrounded by the innocent, like I was Jesus! And me with the Devil in my heart!

« But where was I? I raise my staff and open a path through the herd and go over to where the nanny goats were sniffing the ground and I see a few drops of blood on the rocks. Those drops formed a trail that I followed, with the goats behind me, all frightened like, and then I came on some flattened rosemary bushes, and then the bent branches of some young pines… and then I had a terrible fright…

« ‘Somebody’s been killed here and they dragged ’em to some high boulder!’

« I was just about to go back, but my curiosity got the better of me. If I found a dead body, why should I be blamed? What had I done? But you know, my conscience was always gnawing at me… I go on farther and come to a clearing in the woods and there I see… What do you think? A dog! It was lying there, still, like it was dead, but its round wet eyes were open and its head was covered with bloody wounds. All around it there were big blood-stained stones that somebody must’ve wanted to kill it with. I could see right away it was a real good whippet. I know a lot about those things. I brought it some water from the spring, lifted up its head and let it drink. Later I carried it home like it was a lamb.

« But I didn’t do that out of love. I did it for the same reason I did everything: out of avarice. It was a beautiful dog, a fine breed, worth lots of money… That’s the reason I acted the way I did.

« I nursed it back to health and I tied it to the door on a long chain. But I begrudged everything, so I fed it very little, and one day it broke the chain and got into the henhouse and killed three of my best hens. I went to Castalla to sell it to a hunter. But three days later it was back at the farm. The hunter soon showed up and I had to give him back his money. I took the dog to Alcoi and set it loose in the town square. But it didn’t get lost; it crossed the mountains and reached the farm before I did. The damn thing was grateful that I had saved its life and didn’t want to leave me.

« But then, when it looked like I couldn’t make any money off of it, I started in to despise it. I tied it to the door and gave it one beating after another. ‘You’ll pay for all the food you eat!’

« ‘Don’t do it! Don’t make it suffer!’ shouted my wife.

« ‘Didn’t its other master try to kill it with those stones?’ I answered. ‘This here cur must be a jinx.’

« ‘Maybe its master was selfish and resented the food it ate,’ said my son.

« And I just got madder and madder, because anger is what I had in my heart.

« My wife and son really felt bad for that dog.

« So I decided to kill it.

« One night after supper I took off the chain and I tied a short halter around its neck. It licked my hands! I felt a flash of remorse, of pity; but no, my heart was much harder than kind! I went ahead! I took it to the Quitranera ravine. There’s a high cliff there. That’s where I’d get rid of it.

« I took a rough trail, along a crest with no trees. The moon looked like a tremendous pie plate rising above the cliff, and the few scattered pine trees there seemed to be nestled inside its breast. The whippet followed me tamely; I didn’t even have to pull on the cord.

« I’d left my wife and son at the farmhouse door, tearful and crying out, ‘Please don’t kill it! Is this what you saved it for?’

« The moon shone on the house, but I was too far away to see them clearly. I could still hear them shouting though, ‘Please come back!’

« Soon I heard footsteps behind me. It was my wife! She didn’t utter a word.

« ‘What do you want?’ I asked.

« ‘I’m afraid you might fall.’

« Her voice sounded strange, as though she had died.

« We reached the edge of the cliff.

« The moonlight fell on the dog. That beast wasn’t at all sad. I untied the halter, took the animal in my arms and threw it over the cliff. But that dog didn’t tumble down to the ground as I expected; it just stayed up there in the air, moving its four legs like it was swimming in a pond, and it began to walk on the evening sky toward the moon, and it let out a blood-curdling belly laugh.

« ‘Did you see that?’ I asked my wife, stupefied.

« But when I turned around it wasn’t her; it was my father, poor thing, grey-haired and pale! Just like that day… He still had the bruise on his face, after all those years! And the tears were still on his sunken cheeks.

« ‘Father!’

« ‘Always doing evil deeds, son!’ he said in a sad voice. But he was looking at me with love.

« Then I saw that his feet weren’t touching the ground, and I fell to my knees as though he were Jesus Christ, and I felt dizzy and I closed my eyes and stars were shining inside of me.

« My wife and son found me the next morning and I told them how the dog had walked on the air and the laughter came out of the sky and the moon had the pine trees in its breast and, above all, what my father said and the stars he left inside me to guard me in my sleep.

« I told the story, day after day—one day, the next and the next… and no one believed it.

« I think if I had confessed when I slapped my father, and had been told the kind of serious things that make you weep and repent, God wouldn’t have plunged me into all of this confusion… »