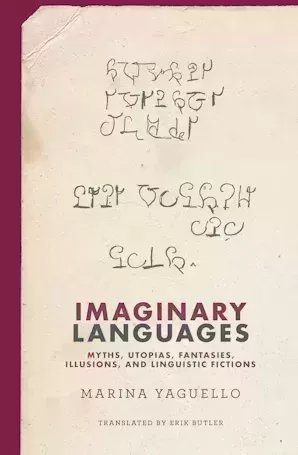

Imaginary Languages: Myths, Utopias, Fantasies, Illusions, and Linguistic Fictions

Marina Yaguello

translated by Erik Butler (MIT Press, 2020), from Les Langues imaginaires: mythes, utopies, fantasmes, chimères et fictions linguistique(2006)

« The myth of Babel represents the necessary counterpart to the myth of the Adamic language, shining light on the mystery of the many tongues spoken by human beings and the lack of concord between them, » writes linguist Marina Yaguello in Les Langues imaginaires: mythes, utopies, fantasmes, chimères et fictions linguistique (2006). That book is now translated from French into English by Erick Butler, as surely as placing a brick back into Babel itself.

Yaguello’s cast of oddballs, eccentrics and geniuses molded their own grammars, hammered out new syntaxes, and crafted complete vocabularies. They mostly left little mark on the wider intellectual world, but to study such inventions is to orbit the idea of language, to see language’s oddness (so obscenely material: fleshy larynx and hard palate, tongue against teeth and the trachea’s vibration) and to marvel at its miracles. To desire some other perfect language is, after all, at once to acknowledge and to overlook the miraculousness of what we have. When visionaries and mystics, and then philologists and linguists, attempted to craft the primordial or the perfect language (often they were the same thing) they were approaching the very coast of utopia, the lowest regions of transcendence. The affliction Umberto Eco called glossomania, Yaguello calls logophilia. Both provide a genealogy of the obsession. The obsession spins off into imperfect but aspirationally « real » languages from Elvish to Klingon. But the discoverers and crafters of perfect languages, Yaguello writes, strove for « harmony, eloquence, straightforwardness, logic, clarity of reference, musicality, symmetry, regularity, and economy … features set in contrast to the harshness and imperfections of natural tongues ».

This article is behind the paywall. Want to keep reading this article?

Subscribe to the European Review of Books, from as low as €4,16 per month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in

- Benjamin Lee Whorf, « Language, Mind and Reality », Theosophist 63, parts 1 and 2 (1942): 281-91, 25-37. ↩︎