Read in: Nederlands (Dutch)

La Pelle

Curzio Malaparte

(1949)

Diario di uno straniero a Parigi

Curzio Malaparte

(1966)

Der europäische Traum: Vier Lehren aus der Geschichte

Aleida Assmann

(C.H. Beck, 2018)

On Curzio Malaparte’s Europe — and ours. The midcentury novelist read anew, on war’s aftermath and transatlantic romance.

It’s the summer of 1941, and as World War II rages through Europe, the Italian writer-journalist Curzio Malaparte is following the German army, reporting on its invasion of the Soviet Union. While traversing the dark Ukrainian steppe on horseback, on his way to the village of Dorogo, « in order to visit the famous kolkhoz which was the breeding-ground of the finest horses in the whole of the Ukraine »1, he experiences something that truly rattles him. It is detailed in La Pelle (1949) or The Skin, a novel written years later, after Mussolini’s Italy had disappeared, or seemed to.

Dorogo is burning, alighting the early evening sky. Malaparte, looking for a place to spend the night, rides forth in an eerie glow. When he slows down a bit to get his bearings, he is startled by voices high above his head. He hears a rustling up in the leaves and branches of the trees that line his path, but can see only the dark outlines of their trunks. Suddenly he hears shrill voices and furious laughter. Or is he imagining things? He thinks he feels the slap of a wing in his face, and tries to reassure himself: « They were of course birds, … crows perhaps, that had been roused from sleep and were flying away, flapping their thick black wings as they made off. » But then, high above his head, he really does hear human voices, in German, Russian and Hebrew, asking: « Who are you? What do you want? » Malaparte doesn’t know what else to do but to answer:

« I am a man; I am a Christian, » I said. A shrill laugh rippled across the black sky. It faded away into the distance and was lost in the night. … Scornful laughter greeted my words. It drifted high above my head into the distance, and gradually died away in the night. « And aren’t you ashamed of being a Christian? » shouted the voice. I was silent.

Malaparte now notices dark shadows moving among the branches. The sensation of the crow’s wing had been a figment of his imagination, a reflex of the brain trying to reason away the unconfrontable truth. There were men hanging everywhere above him. They were crucified on the trees.

Since 24 February, 2022, Malaparte’s trek to Dorogo has regularly returned to me. Not only because of the accounts of barbaric Russian violence in Ukraine, but also because of a certain inability to truly know and understand that barbaric reality as such, and a subsequent feeling of shame about that inability. The rhetorical question aren’t you ashamed? is, to me, the key question for today’s Europe — the Europe of European integration. Yet this very question, the question that silenced Malaparte on that summer evening in 1941, is the one we’re not hearing — let alone asking.

I keep wondering how it’s possible that Malaparte, with an anecdote written in 1949, could look the brutality of today’s reality straight in the eye — while we in our time seem to be looking away. What insights does his writing contain that we’ve lost over the decades? What delusions afflict what we call our shared European history? Was the ethical power of the postwar « West » — for which we in Europe still so readily and unabashedly reach to guide us and to legitimize our actions — a comfortable illusion? What is this « postwar Europe », anyway?

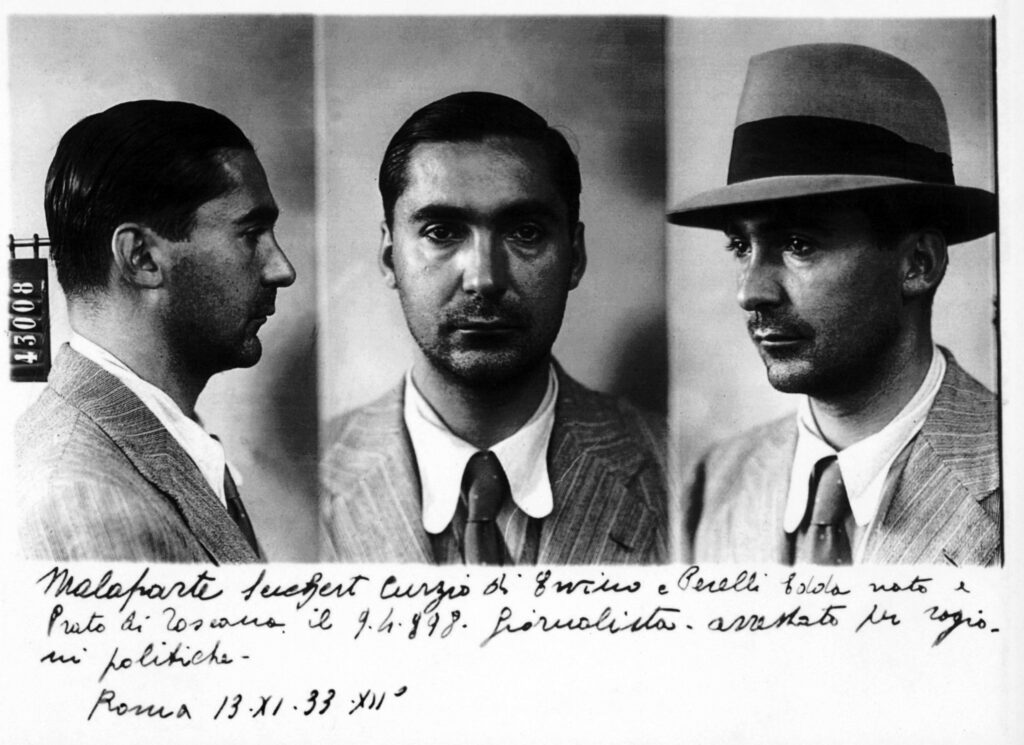

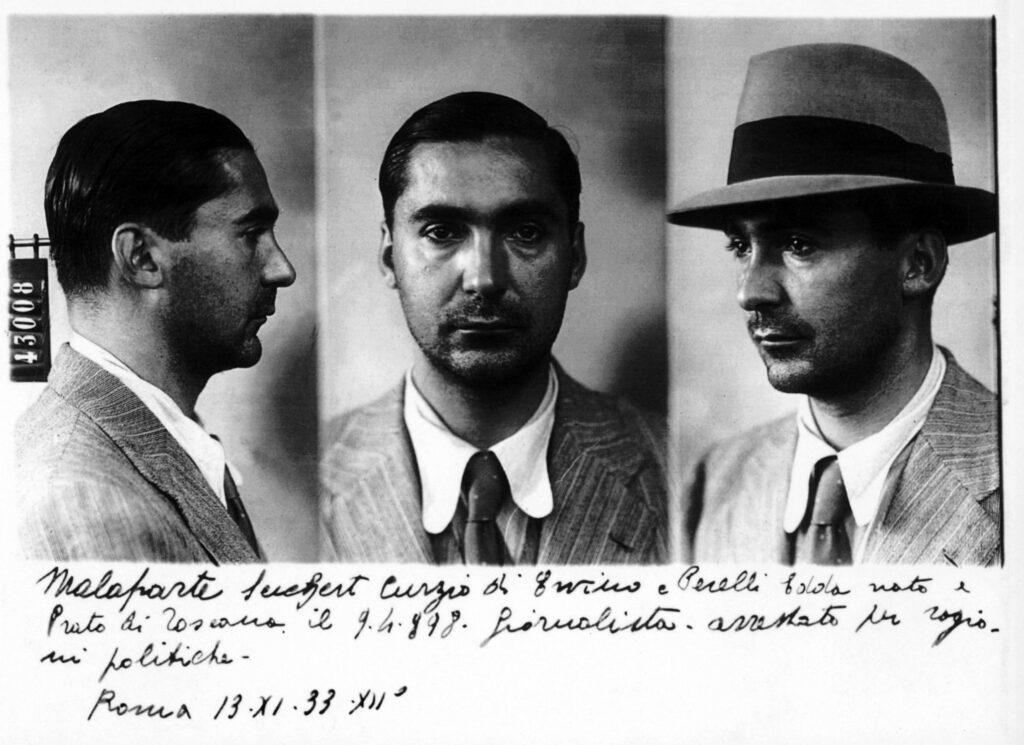

Curzio Malaparte was a spirited and unconventional researcher of the European Zeitgeist. Born in 1898 in Prato, Tuscany, he became a master at sketching the peculiarities and preoccupations of European nation-states and their populations. He captured, too, the brutality that colored their histories with false glory. His Europe was made maniacal by war and violence. Malaparte immersed himself in that mania for years. As a diplomat and a war reporter for Corriere della Sera, he traveled all over continental Europe through the darkest days of World War II — very often directly along the front line.

What is this ‘postwar Europe’, anyway?

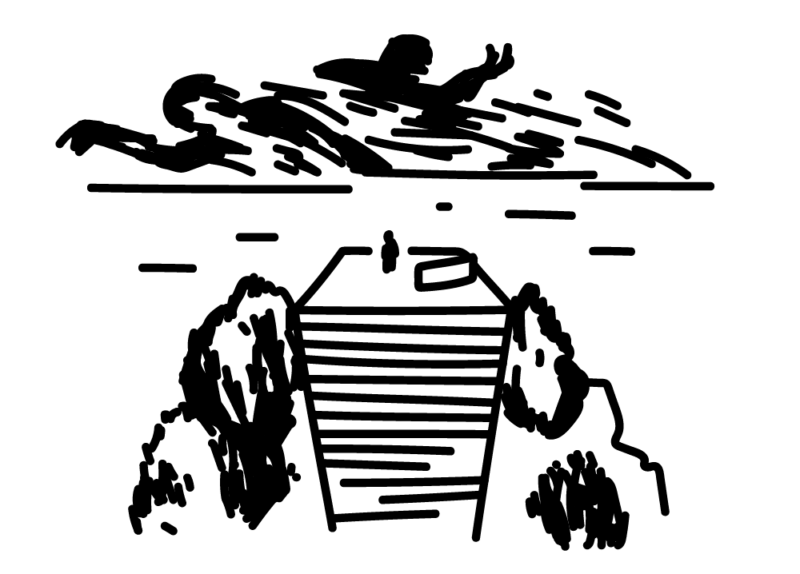

Casa Malaparte

Casa Malaparte

His two best-known books are novelistic reports of these travels. Kaputt (1944) contains the staggering account of his odyssey across Italy and Yugoslavia, through the « Bloodlands » of Central and Eastern Europe — deep into Romania and Ukraine, to the crystal-clear lakes and seas of Lapland, Karelia and the Gulf of Bothnia. His reporting delivers an almost endless series of tragic stories — confusion, dirty politics, lurid consumption, hardship, hunger, grit, bones, skin and blood — alongside burning love, and a devotion to art, culture and nature. Reading it is at times an almost physical experience. The Skin reports on the obscene pandemonium into which the 1943 liberation of Naples had degenerated, in which everyone tried to sell their skin as dearly as possible; a harrowing feast of new and old unfreedom, shadowed by death, lust and destruction. The key message here: the surface deceived. This was true of the liberation’s surface, too.

In his own life, too, surfaces deceived. Not only did the Italian Malaparte have a German father, the fascist Malaparte transformed into an anti-fascist in the 1920s. That led promptly to his imprisonment, and later his exile to the Sicilian island of Lipari. But after those banishments, the pragmatic Malaparte cooperated again with Mussolini’s regime, especially through his friendship with Il Duce’s son-in-law. His work as a war correspondent was well financed with fascist money, and he gathered enough capital to have his now-mythical house, Casa Malaparte, built on a rocky point of the island of Capri off the Neapolitan coast (the setting for Jean-Luc Godard’s film Le Mépris [1963]). At the same time, however, Malaparte ran a literary magazine called Prospettive in which Jewish intellectuals, such as the Italian writer Alberto Moravia, could continue to publish under the fascist regime. On July 18, 1957, the day before he died from the long-term effects of the mustard gas he had inhaled as a 16-year-old soldier in the French trenches of World War I, Malaparte was granted his coveted membership in the Communist Party.

When the liberation of Italy began, Malaparte was a liaison officer for the U.S. Army. The experience moved him deeply. He was grateful to the Americans for the simple and naive hope they brought, a gift amid all the misery, lethargy and tainted grande bellezza. The American soldiers in his account understood nothing of the dark and sinful Europe in which they found themselves, and this is why he loved them: « The Americans are not cynics, » he wrote in The Skin, « they are optimists; and optimism is in itself a sign of innocence. … They do not know, although they are in many respects the most Christian nation in the world, that without evil there can be no Christ. » He could not do without their illusions:

In that terrible autumn of 1943, the pure and honest simplicity of their ideas and sentiments, the genuineness of their behavior, instilled in me the illusion that men hate evil, the hope that humanity would mend its ways, and the conviction that only goodness — the goodness and innocence of those splendid boys from across the Atlantic, who had landed in Europe to punish the wicked and reward the good — could redeem nations and individuals from their sins.

Malaparte’s declaration of love to the Americans is ambiguous. There’s an irony in that portrait of American naiveté, and yet in his Italian vale of tears, his declaration is sincere. Malaparte inhabits the persona of shattered Europe, with its desperate needs. And that quintessential American sincerity — nay, simplicity — turns out to be a much more effective therapy for the trauma and open wounds of war than the traditional « European » way of fuss and flagellation. The Americans offered exactly what Europe had lost: hope and ideals.

What was true for Malaparte was true for all of Europe: without America and American hope, progress was impossible. In the Americans, Europeans saw their dreamed mirror image. En passant, this moment in the novel captures the curious and strangely sweet transatlantic clash of civilizations — the twists of attachment, dependence, caricature and delusion — on which today’s « Europe » was founded. But this relationship was, as is so often the case with yearning love affairs, unequal, born out of need and desperation. It may have provided new hope for Europe, but how solid was it? Could Europe exist without America, leader of the West?

In the current context of war in Europe, these questions become inescapable. Our united postwar Europe has operated as a « clearing-house for European history », which is to say that it has settled a balance without judging the bank. 2How did that work? Alongside the process of cooperating and amalgamating in an economic and financial sense (through the clearing of disparate national economies), integration also offered a very special clearing of a different sort: the secure settlement of emotions between European countries, facilitated with American money. There are still two codes for access to this clearing-house: an understanding of one another’s sensitivities, and discretion. The latter is mostly achieved in the form of technocracy and policy (a successful recipe to tame ideology and stifle public debate). But precisely this discretion also distorts facts and obscures tensions and discords between those European nations. War has a way of unobscuring things.

Meanwhile, the American example no longer stands. Their money and weapons are still here, but they themselves are gone, and the love hasn’t lingered. The American arms in Ukraine aren’t like the liberators of Naples and Paris. The dollars streaming into the region today aren’t like the Marshall money of the past. The dreamt-of mirror image has become distorted. The Malaparte of The Skin dramatizes an eerie Vergangenheitsbewältigung-in-advance: participating in a romance while sensing its cracks. Its doom could be experienced simultaneous to its consummation.

But from the other side: what was it about that love affair with Europe that carried away the American elite?

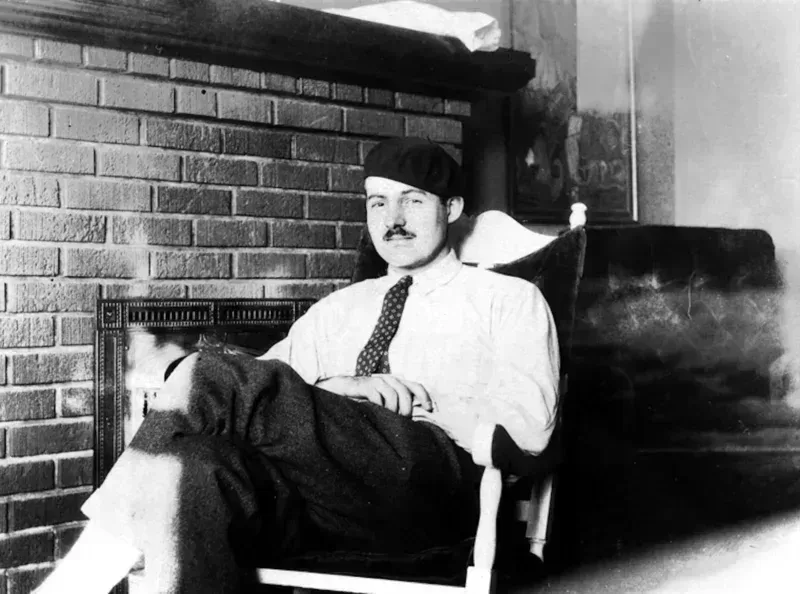

In August 1944, a Jeep raced across the Place Vendôme in Paris. On board: Ernest Hemingway, the American soldier-writer who had survived World War I, the Spanish Civil War and life in the artistic fringes of 1920s Paris. Since D-Day (June 6, 1944), Hemingway had been on a mission: liberating the Ritz, the hotel of his nostalgia, which had been frequented during the occupation by Hermann Goering and Joseph Goebbels. When Hemingway, armed with a machine gun, jumped out of his Jeep and into the hotel, there wasn’t a Nazi in sight. He ordered a tray of dry martinis at the bar.

Ernest Hemingway,

at the Ritz and at

war

At the Ritz and at war

Hemingway had grown older. His truly wild years were behind him; the present was a mere echo. The original hero of the hard boil was suffering from the aftereffects of a concussion, and from the dissolution of his marriage to Martha Gellhorn. This Paris was no longer his Paris. He’d written about his Paris in the 1920s; in 1964, his recollections would be published posthumously under the title A Moveable Feast. In November 2015, this somewhat forgotten little book became an instant bestseller in France in the days immediately following the terrorist attack on the Bataclan theater. Hemingway’s Paris — an exuberant social concoction of drinking, dancing and dining — apparently provided a form of comfort. It offered the handholding that only an American in Paris could provide: the shoulder and chest of a good guy, the kind they only made in the USA. Tough and a little wild, loyal and full of possibility: the American dream personified as man, writer and mentor.

Looking back now, that Western European backdrop against which the 2015 attacks took place seems a simpler, more innocent time. In the United Kingdom, former Bullingdon Club members were bickering about whether or not to hold a referendum on what was then called « Brixit ». On the other end of the Atlantic, as Barack Obama entered his final year as president, a Donald Trump election was unimaginable, at least to those who pretended to understand the West, its past and future.

One of Hemingway’s fellow travelers in the Paris of the 1920s was David Bruce. Bruce was a young and handsome superrich son of the American South. He’d inspired the character of Amory Blaine in F. Scott Fitzgerald’s This Side of Paradise (1920), the literary sensation of its moment. In 1949, one lost generation later, Bruce would become the American ambassador to postwar France.

On a warm night in June of that year, Bruce returned to the Ambassador’s Residence and wrote an entry in his diary. Usually those diaries, which can be found in the Historical Archives of the European Union in Florence, consist of notes referencing negotiations, behind-the-scenes phone calls, state visits and other ambassadorial concerns. But that night Bruce jotted down something very different. He had just returned from a party at the home of the middle-aged French actress Yvonne Printemps. She had sung some romantic songs while stretched out on the wooden floor of her apartment, sheet music scattered around her like leaves in autumn. Bruce, still under Printemps’ spell, wrote that he remembered the 1920s in Paris, and how even then he had lost his heart to her. She was, to him, the essence of femininity and the embodiment of the spirit of Paris.3

I’ve reread this atypical diary entry many times. What did Bruce want to hold onto with it? What had revealed itself to him that night? Any answer is an impressionistic shot in the dark, but when I try, I see this: the American ambassador, who was responsible for administering the Marshall funds, sees this actress in her natural habitat, and recognizes in her the core of his drive to do good in a Europe fighting poverty and hunger. He is reminded of the Europe he had fallen in love with in the 1920s. I also see a man who feels this ideal image of Europe fading away, and must acknowledge: I am getting old, she is getting old. He glimpses the coming end of the affair.

Bruce was a child of the generation that laid the foundation for, and built, the American Century. The peace negotiations after World War I were America’s « geopolitical coming-out party », his biographer notes.4 Bruce’s cohort, representing a new, outward-looking America, drank the self-confidence that came with their ever-growing position of power in the world, their ever-growing American economy of consumerism and plenty, and the ever-more-favorable exchange rate.

Nowhere could this self-confidence be more freely exploited than in the Paris of the 1920s. The city was theirs, and the goddess Europe was a femme fatale, the kind they only made in France. Sinclair Lewis, a staple in the American entourage on the rive gauche, likened their clique to « iridescent flies caught in the black web of an ancient and amoral European culture ». The smitten Americans in the 1920s affectionally called this other, earlier postwar Europe — dangerous, traumatized and impoverished after the war — « la banlieue de Paris ».

Malaparte recorded both the line from Lewis and the characterization of Europe as the banlieue of Paris in The Skin, a book in which everyone does everything to save their own skin as the value of human life plummets. The apotheosis of this sad absurdity comes when an American tank accidentally runs over and flattens a Neapolitan man celebrating the liberation. (Liliana Cavani’s film adaptation, from 1981, was accused of sensationalism for its rendering of the scene.) The event reminds Malaparte of an earlier scene, witnessed in Ukraine: a « carpet of human skin lying in the dust of the street right in the centre of Yampol, a village on the Dniester ». The human carpet was picked up and carried around like a flag. « That’s the flag of Europe, » our narrator tells his companion. « It’s our flag. » I myself was reminded of this image when I saw a picture on Twitter of a similarly flattened Russian soldier in Ukraine, alone in the dust, our own era’s stained human flag.

That was the context both for Malaparte’s emotional dependence on the Americans and for his feverish implosion of that dependence. In retrospect, few had a keener eye for the fatal fragility of what is beautiful in Europe. When he was finally back in Paris in 1947, Malaparte went to the theater to see his favorite actress, the Jewish Russian-born Véra Korène. He had to admit that he no longer felt at home in Paris. He too kept a diary about this confusing time, later published as Diary of a foreigner in Paris, in which he goes in search of a truer Europe, the Europe without the frills of Enlightenment, without America.

The human carpet was picked up and carried around like a flag.

Of course that Europe is lost, and is powerful precisely because of its lostness. Véra Korène’s contact with the lost Europe, of Racine and Tasso, is a singular miracle. She keeps the door to Das Reich der Mütter (the Realm of Mothers) from Goethe’s Faust always slightly ajar. 5Malaparte yearns for and laments that lost world, and the « European » virtues that went with it: forgiveness, resurrection, melancholy and remorse. The two of them, Korène and Malaparte, were now the last Europeans in Paris.

Or in Malaparte’s psychoanalysis: Paris was no longer Paris, Europe was no longer Europe. Kaputt. Those classic European virtues were supplanted by soulless and transactional can-do concepts like tolerance. This new era’s trend-setting mavericks were no longer artists and writers; they worked in advertising. One September evening, Malaparte sat down to dinner at the invitation of the French general Béthouart, who had served in both World Wars. Location: the expensive restaurant Maxim’s. His diary sets an aesthetically and morally crowded scene:

In the gilded frame of Maxim’s, everything takes on an easygoing, debonair aspect, with an elegance that retains a good deal of the Toulouse Lautrec poster or the devil-may-care attitude of the Prince of Wales, Edward VII, during his Parisian escapades. And yet there is more alte Wien in this very famous late-night restaurant than Parisian entente cordiale.6

He pays close attention to the women in Maxim’s that night — not the Americans, but the Europeans, the Françaises in particular:

Their evening gowns — and I don’t know if it’s the fashion or modesty, a strange kind of modesty, strange for a beautiful young woman — jealously hide their shoulders. […] The war, those brutal and shameless years, has left a trace of virginity, this strange modesty, in them. They are composed, reserved, cold, almost severe. Unfamiliar. […] Such modesty is the sign that the women, too, lost the war — a war that everyone, winners and losers, lost.

Curzio Malaparte, in

exile and in church

In exile and in church

Malaparte arrives at a gendered logic of shame, layered with irony and paradox. (The Italian term pudore encompasses both « shame » and « modesty »; the English translation deploys « modesty », which feels too thin.) In men, the shame « generally manifests itself as despondency, pessimism, or poor manners, as boorish acts that no one questions and of which they themselves are perhaps not even aware. » In women on the other hand, because they are « more sensitive, more intelligent, more active than the men, in France as well », pudore « manifests itself in this reluctance to display, even in the most appropriate ways, their nudity. » This anatomy of shame does him good. He is « very grateful to the women in this country […] for offering me a face of France that is not that of futile, frivolous, superficial life, for showing me their soul only through the veil of modesty. » And from there, a continental diagnosis: « One truly needs modesty in Europe today, to stroll among so many ruins. » The women have it; the men do not.

Shame is an emotion both social and deeply personal. The fear of being despised requires, after all, a certain projection, even a perverse empathy, since one has to put oneself in another’s shoes and then imagine them despising you. And then, suddenly and clearly, seeing your despicable self from their perspective, you want to disappear. I’ve revisited Malaparte’s writing about shame many times lately; it illuminates an emotion I suspect we have paid far too little attention to. A sense of shame would have been an essential element of life in Europe after the war, among the « many ruins ». We may have missed entire currents that shaped contemporary history, because the non-artists (or the non-Malapartes), with their can-do attitude, weren’t able to perceive the incongruities between their perspective and the perspectives of those they dominated. Shame was inevitable. By glossing over that shame, part of who we were was obscured, even renounced. Our skeletons were hidden.

Through those sprawling and stylized generalizations on women, men, and Americans, Malaparte was very much on the trail of that postwar European sin. The women in his restaurant scene have a much better understanding of the depth of Europe’s confusion than the men do. It is manifested in their sternness and in the subtlety of their actions. Their feeling of shame connects Europe’s recent past with its future — and they leave the present for the men. Malaparte’s men inhabit the perspective of Henry Ford, Macher of the American century, who’d said during the earlier war that « History is more or less bunk. It’s tradition. We don’t want tradition. We want to live in the present and the only history that is worth a tinker’s dam is the history we make today. »

And what of today? A love affair is never without consequences. There is a life before and after the love, before and after the commitment. For Europe and America, one thing is certain: the time of opposites attract is definitely over. At the turn of the millennium, the American political scientist Robert Kagan put them on different planets: « Americans are from Mars and Europeans are from Venus; they agree on little and understand one another even less. » That wasn’t just a misogynistic interpretation of world politics; it was an announcement of a new era, in which Europe slowly but surely comes to stand alone in the world.

That was twenty years ago. Who among today’s European thinkers and historians reflects on this uncomfortable reality? With Malaparte in mind, I went back to the analysis of contemporary European history that most impressed me in recent years: Der europäische Traum (2018), by Aleida Assmann, professor (emerita) of English and general literature at the University of Konstanz. Assmann writes that we are now experiencing the end of the West. The door of that claim has been wide open for a while, but Assmann pushed beyond mere diagnosis. Her book was also an urgent call for the Europe of European integration to become more self-critical through a deeper understanding of its own history, to remedy the forgetting on which it was founded.

That foundational forgetting wasn’t quite the same thing as repression. On the contrary, in Assman’s account, forgetting was seen as a practice of liberation. Winston Churchill, she recalls, called already in 1946 for a communal forgetting, that would allow Germany and Italy back into the arms of the allies and thus look to the future. But this was nothing new in the Europe of war, blood and soil. It was the crucial formula in the 1648 Peace of Münster, the birth certificate of the European nation-states: perpetua oblivio et amnestia, forgetting and forgiving. This took a particular form, of course, in postwar Germany. After the Stuttgarter Schulderklärung der evangelischen Christenheit Deutschland in the autumn of 1945, and Karl Jaspers’ 1946 publication Die Schuldfrage, confronting German readers with the crimes of the Nazi regime, the soil of German history had been made fertile enough to cultivate according to the geopolitical reality of the Cold War, and Konrad Adenauer’s Christian Democrats could then aspire « where it appears acceptable to do so to put the past behind us ». Meanwhile, in Tony Judt’s account, the Italian newspaper of the new Christian Democrat Party « put out a similar call to oblivion on the day of Hitler’s death: ‘We have the strength to forget!’, it proclaimed. ‘Forget as soon as possible!’ »7

An unforgetting is more important than ever, Assmann argued, now that the ideology of Europe — symbolized by the circle of stars as a sign for unity in diversity — is rapidly losing its credibility. Many of the conditions inside and outside the Europe of European integration clash with that ideology. The European self-image as a beacon of reason, freedom and democracy can quickly become a sordid mirage. And that self-image is the historical product of a distorted collective memory, structured by the inept handling of violence-induced trauma.

A breakthrough, according to Assmann, requires a crucial mental step: renouncing that other dream, the American one. Renouncing the idea that Europe can save itself by following the American example; that clearing European history sufficiently reckons with European history; that politics and ideology can be kept in eternal check by technocracy and policy; that the world consists of good actors and bad actors. The anchor of that dream, Assmann argued, has come loose, and Europe needs to find a sturdier anchor, to descend more deeply into the same history. That isn’t easily done. Regression therapy is a form of mental health care, sure, but it is also a flogging for mind and soul. I would love to know how Assmann reads Malaparte, what she wants to see in the place of an American Europe. Whether a new dream can become a new nightmare, and whether she is afraid of that.

After all, we do live in a time of Umbruch, upheaval. It’s both concrete and ambient; one feels it in the harmonics of social psychology. We can think of it as a reawakening of a consciousness formerly numbed by silence and forgetting. Malaparte’s Europe was never really gone, only forgotten. And we still live in it. The clearing-house of European history couldn’t really clear that history, for it is an endless exercise. And a clearing-house, in any case, is not for living in. Malaparte reported on that endless exercise — the tears, the alienation, and the comforts to be found in corners here and there — which is what made Europe, despite itself, a home. A home for the eternal practice and the eternal illusion of living together.

- English translations from La Pelle: Curzio Malaparte, The Skin (NYRB Classics 2013)> ↩︎

- The phrase « clearinghouse for European history » is inspired by the era’s own vocabulary: « Ecumenical Inquiry on Christian Action in Society », World Council of Churches Study Dept. (Archives of the WCC, Geneva), 14 October 1949, as cited in Clemens van den Berg, « European Believers: Ecumenical Networks and Their Blueprints as Drivers of European Integration, 1933-1954 » (PhD-thesis Utrecht University, 2022). ↩︎

- Historical Archives of the European Union, Florence, Jean Monnet American Sources, 106-114, David Bruce Diaries. ↩︎

- Burton Hersh cited in Nelson D. Lankford, 1996, The Last American Aristocrat: The Biography of Ambassador David K.E. Bruce (Boston: Little, Brown and Company), p. 42-3 ↩︎

- In Das Reich der Mütter live the primal forms, of which reality is a reflection, both the dark and the brilliant. ↩︎

- Curzio Malaparte, Diary of a foreigner in Paris (Eredi Curzio Malaparte/NYRB Classics, 1947/2020), Sept. 18, 1947. ↩︎

- Quoted in Tony Judt, Post-War: A History of Europe since 1945 (Pimlico, 2007), p. 61 ↩︎