published in Issue Four

How I stopped being an older brother

I was five years old when my parents brought me from beyond lake Baikal in Siberia to Chernivtsy in western Ukraine. The whole family came: mother, father, my older brother Valentin, and me. In Chernivtsy I was the younger brother, but because I was an emissary of imperialist Russia in colonial Ukraine, I became an older brother to ancient Hutsu

As I grew up, I was a model older brother: I sympathized with the younger ones. I didn't look down on them, and I even took an imperial interest in learning their language. But when I was about eighteen, I realized I no longer wanted to play this game, or count myself among the infinite millions of Russians who, without a trace of irony, called themselves a « great nation ».

In 1965, at almost my first lecture as an undergraduate of Chernivtsy University, I understood precisely why. The professor teaching the « History of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union » course asked what language we wanted him to use, Russian or Ukrainian.

There were about sixty students. The fifty or so Ukrainians among us said nothing. But ten older brothers chorused: « Russian! » I think that was the moment it first hit me that the Soviet myth of the empire as a friendship of the peoples was a farce, and that the Soviet Union could not last much longer.

I was wrong. It kept going for what seemed an interminably long time: not in terms of history, but in terms of a single person and his one and only lifetime. But in the end it came crashing down, flushed down the historical tubes, gone to hell with all the concomitant chthonic horrors. By then I was in England and absorbing invaluable lessons in the national and colonial sobering-up process. But right up to my departure from the USSR, I was trapped in the older brother routine. I felt this even when interrogated by the KGB. They belittled me, mocked my literary ambitions, but they didn't smash my face in and lock me away in a loony bin or grind me into the dust of a labour camp, like they did with my colonised and more vulnerable younger brothers.

Meanwhile, in England, I shed years instantly. I became a younger brother again, in the literal sense, a younger brother to Valentin.

In November 2008, I went to Vienna to take part in a festival of Ukrainian literature. In addition to a Romanian and an Austrian, I had been invited as a Russian writer with a Ukrainian connection. I read my work alongside half a dozen or so Ukrainian writers and poets. I felt at ease: I liked playing the part of a national minority. I enjoyed the joke Clio, the muse of history, was playing on me. Now, at 60, I felt a boy again, the same little lad who once upon a time was growing up in Siberia and loved his mother, father and older brother Valentin.

A six-letter word

I am, the phantom sang, I am the Siren sweet.

Dante, The Divine Comedy

« Above » or « below sea level » are things we learnt about in geography lessons. « Above » means mountains. Some are so high you can’t see the sea from them, not even with binoculars. « Below » are basins, salt and freshwater lakes, tunnels built through mountains and under straits by the engineering geniuses of modern times. But the phrase « below land level » is not something you meet often. Though we did read in school about the Ancient Greek « Kingdom of the Dead »: about otherworldly rivers, the coin in the mouth for the ferryman, the howling three-headed dog and other Underworld joys. And then there’s the crossword clue, down and across, six letters: premises below ground level. It would work better as a down, I think. CELLAR. You can store whatever you fancy down there: leaky bowls, battered scooters and sledges draped in cobwebs, clothes horses with bent wires, a rusty watering can with last year’s mud stuffed into the holes. It’s perfect for games of cowboys and Indians or hide-and-seek — « Coming, ready or no‑ot. »

In modern history cellars have played a not insignificant role. I read a story once about a Bordeaux wine dealer during the Nazi occupation who blocked off part of his cellar with a plywood wall, painted it to look like brick and hid a whole family of Jews behind it. This dramatic story had a happy ending.

In Ukraine today cellars are also proving their worth: people and pets take shelter from Russian bombs. Broad-shouldered men have rolled down steel barrels for washing, carried down cooking equipment, and fetched sand boxes and drinking troughs for the cats and dogs. Canny women have collected rain water in plastic containers and three-litre jars and organised play areas with chess, dominoes and cards so the kids don’t get under everybody’s feet. The IT people have set up wi-fi and university professors give lectures online. The dulcet tones of the sirens barely make it as far as the cellars.

Can you buy me a new suitcase?

Mitya’s mother arrived from Mariupol. It had taken him ages to persuade her to move to Prague. He kept on at her: « The Russians are killing you, mum. Your students have all run away. I’m begging you. On my knees, mum, I’m begging you ». Mitya’s childhood friends helped, and she made it to Prague. She brought her parents’ old suitcase, covered with fabric and with brass fittings. It had disintegrated on the journey: « I had to live out of it for several days ». His mother arrived, collapsed into a chair and refused to get up.

« Want some soup, mum? »

« Fish soup takes three hours over an open fire. It needs an hour to heat a pot of water ».

Mitya collects antique china. The glass-fronted cabinet was crammed with Bohemian tea sets, glazed and gilded, cruet sets, Carlsbad and Marienbad spa cups. Mitya said: « Come and see, mum. You always liked Czech crystal. » But his mum didn’t come over and didn’t want to hold the china. Mitya said: « Let’s go up to Prague Castle, see inside the cathedral, have a look at the Baroque fortifications, then walk down to Golden Lane, where Kafka wrote A Country Doctor and used to meet his fiancée Felice. » His mother snapped back: « That doctor ended badly, and Kafka got TB and never married Felice. » Mitya told her he’d arranged Czech language lessons for her at the Natalya Gorbanevskaya School

The gaps between words

Thank you, Professor Jaspers, for developing the concept of « limit situation » (Grenzsituation). Let us expand its limits. It’s not just individuals. Nations, too, can face threats and mortal danger. We see the body of Ukraine fighting heroically right now for its existence. For a writer, the « limit situation » extends into the realm of language. The act of writing presupposes an extreme intimacy with language. Death is also an extreme. Where exactly is the boundary between one language and its neighbours? Can one language threaten another? Of course it can. There are loads of examples: through love, hatred, indifference, there are so many ways to skin a cat.

In James Joyce’s novel A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man there is a curious episode: a conversation between the hero, Stephen, and an English clergyman (a Dean) about language. They begin with an innocent discussion of the words funnel and tundish. Afterwards Stephen has to admit that English belongs in the first instance to the clergyman and only later to him, the Irishman. For him English will forever remain borrowed. « The language in which we are speaking is his before it is mine. His language, so familiar and so foreign, will always be for me an acquired speech ». At the end of the novel Stephen comes to the conclusion that the Irish version of English is a language that has been picked up, and decides he will use it as a tool, if only to express the captive soul of Ireland.

This incident from Joyce’s novel sprang to mind when I was reading a piece by a British author, my son Peter, who expressed the thought, unexpected for me, that when he writes in English he feels the burden of the sins of Empire and is ready to bear it.

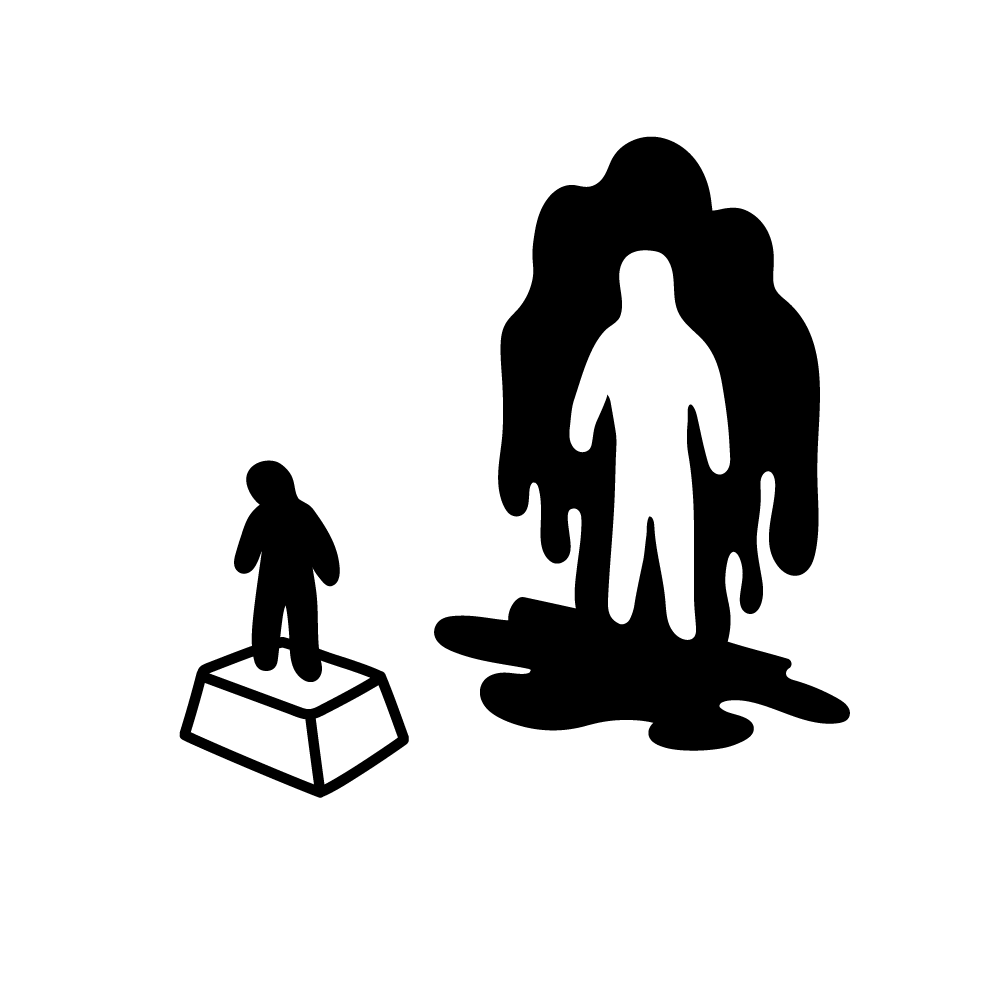

Joyce is warm. Peter is hot. All my conscious — pre-Western — life was spent in Ukraine. Was spent, but remained there nevertheless. Russian was always my native language. War is a limit situation not just for the speakers of a language, but also for the language itself. The murder of a nation is the murder of its language as well. I am a writer and I love my mother tongue. Today my love still holds, but it has become difficult, dramatic. Evil is polyglot. It speaks hundreds of languages. But it has its favourites, one might say native languages. The German poet Paul Celan, with whom I share a city — Chernivtsy (Czernowitz), wrote a classic poem about evil. Its title is Death Fugue. The key line reads: Death is a master from Deutschland. Today death wears a different uniform, different patches. Now death is a master from Russia and we are bound by one language. But I will not yield it a single pronoun, not a single space between words.

P.S. James Joyce used seventy languages in his last novel, Finnegan’s Wake, including English. Three cheers for the stubborn Irishman.

Who I did not become and how

When my twin grandsons turned three I tried an experiment. I stood Jacob in front of a full-length mirror and asked : « Who’s this? ». Without hesitation, Jacob answered: « Isaac ». Then I asked Isaac the same question before the same mirror. « Jacob », he replied with absolute assurance. I drew the conclusion that very young children lack the capacity for abstract thought. Try explaining to them that a chair or a table is made from wood, which comes from trees in the forest, which have to be chopped or sawn down by a lumberjack before they are taken to a furniture factory.

And how do adults see themselves from the outside? What is their relationship with the « I »? I can speak for myself and my family. I recall critical and unexpected situations. When I was being interrogated by the Kyiv KGB in the mid seventies of the last century, the officer asked me: « Who do you feel you are? Russian or Jew? » I knew immediately this was a set-up and when he got the answer he expected, he would say: « Yes, you’re Russian, a patriot. So how could you get mixed up with all that riff-raff? » But I turned the tables on him: « I am Ukrainian. » The Major spat back: « Stop taking the piss. »

Both my parents were born in Ukraine, my father in Odesa and my mother in Kharkiv, both of them Russian-speaking cities. In 1941 they fled before the invading Wehrmacht to the Russian heartland. Some years after the war they returned to Western Ukraine where my father found work for a Ukrainian-language newspaper. In my father’s internal passport his nationality was listed as Jewish, my mother’s as Ukrainian. At home we spoke Russian. Since I wrote in Russian, I automatically was considered Russian. For me to say « I am Ukrainian » was not a simple statement of ethnic identity. It was a political statement, a refusal to accept the Communist Party’s rules of the game, the Soviet status quo.

Two years after this interview with the KGB I landed with my wife and nine-month-old son at Vienna airport, a homeless and passportless vagrant. We were met by German friends and taken to a pension. The next day I went to the Tolstoy Fund and told the woman at reception that I was a Russian writer and wanted to ask the Fund for help in setting up in Paris. The woman asked whether I was a member of the Writers’ Union. « No, » I replied. Had I been expelled from the Writers’ Union? « No, » I said. She went into the next room, and after a few minutes came back: « I am sorry, but we cannot help you. » And so I was not accepted as a Russian writer. Three days later we were in the Federal Republic of Germany and acquired an official status: « political asylum seekers ».

Istanbul was an early trip abroad. I had dreamed of Istanbul since I was little. A fairy tale city. At the airport the Turkish border guard scrutinised my German « Geneva passport » closely. He gave it back eventually, saying, « Welcome, Mister Saratov ! » I was quite taken aback. Later I looked up Saratov in the encyclopaedia and discovered the word was of Turkish origin and means « yellow hill ». Saratov was where I was born. When I was just a few months old my parents moved to Siberia, to Chita (a name of either Evenki or Uyghur origin). So my « I » acquired an Eastern limit.

But getting back to my grandsons, or more precisely, their father Petya, who became Peter in London. At school he soon acquired a nickname: « Russian spy ». I know who gave it to him. One of his classmates was the son of the spy novelist Frederick Forsyth, and the boy quickly figured out what Peter’s mission was in London. The moniker didn’t stick, though, because Gorbachev’s perestroika and glasnost came on the scene and Russia became fashionable.

I have to say, Peter’s London school was one of the best and when he went to Edinburgh University he was ribbed for being an « English imperialist. » Riding his bike one day he heard somebody shout after him: « Fuck off back to England! » Peter couldn’t work it out. How you could tell he was English just by seeing him from behind?

Peter did fuck off, except it was to Moscow, where he worked on EU-funded projects. He thought that at least here he could blend in and be « like all the rest ». One day he got into a Moscow cab, and all of a sudden the driver said: « No, sonny, you’re not one of us ». Peter couldn’t believe it. He was being taken for a spy again, a British one this time. « You’re from

But what about Jacob and Isaac? They were born in Moscow. When Peter told me the boys’ names I gave him some advice: « In Russian they’ll be Yasha and Izya

Ukrainian ethnic group in the Carpathian Mountains

Natalya Gorbanevskaya, 1936-2013. Russian poet and civil rights activist. One of the eight protesters to walk out onto Moscow’s Red Square on 25 August 1968 to protest the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia.

Ancient city to the north of Moscow, played an important role in Russian history and culture.

Yasha, Izya. These diminutives would immediately identify the boys as Jewish, and hence subject them to ridicule and discrimination.